Reading time: 40 minutes

…I have sat in my living-room with my mother and father at home and seen a rugby league representative take sheafs of pound notes out of his pocket…but…I have never wanted to be paid for playing rugby…

~ Gareth Edwards, Gareth: An Autobiography, Stanley Paul & Co., 1978, p91. As Edwards makes clear in The Autobiography (Headline, 1999), his 1978 book professionalised him in the eyes of the WRU and he was barred from coaching.

…when I went, I said the right things in the Press…I ‘needed a new challenge’…that was bullshit…I needed security for my family…

~ Jonathan Davies, The Rugby Codebreakers, BBC documentary, 2018

In a parallel universe

It’s December 26, 2023. Camborne Town RLFC are hosting their traditional Boxing Day clash with arch-rivals Newton Albion RLFC. Today’s edition marks 110 years of the fixture, which kicked off back in 1913. Both Western Super League teams are at full strength, and the Town Stadium carpark (once a recreation ground), is jam-packed. A capacity crowd of 20,000 is anticipated.

Before the 26 players take the field, Sky’s Brian Carney and Jenna Brooks interview the teams’ coaches pitchside in front of a film crew. Over in the Bill Biddick Stand (Biddick being of course the legendary Town skipper who led them to their first Challenge Cup victory in 1927), one gnarled old-timer turns to his mate and asks,

Didn’t Town used play another team on Boxing Day, years ago?

To which his pard replies,

…Yeah, used be Redruth, but that’s going way back now…

Camborne haven’t played Redruth RFC since 1912…

Of course, none of the above is true. Camborne RFC has only ever played Rugby Union. ‘Newton Albion’ never existed. The Boxing Day game between Camborne and Redruth is part of Cornwall’s most famous – and bitter – sporting rivalry1.

Yes, it’s fiction. I made it up. But, once upon a time, Camborne strongly considered leaving the RFU and throwing their lot in with the Northern Union (from 1922, The Rugby Football League) to become a professional sporting body. They would have joined what was known as the ‘Western League (Northern Union)’, an entity based in Devon.

Therefore, something like the little fantasy above may very well have happened. ‘Camborne Town RLFC’ may have actually existed, mainly because of the antics of two Camborne players, back in 1912…

The day their lives changed

It’s Saturday, April 13, 1912. Cornwall’s rugby season is drawing to a close. Redruth are the Cornish Champions. So are Camborne – obviously, the Press couldn’t decide who should be awarded the title. There was nothing to split the two deadly enemies on the field either; after three fixtures, both had a victory apiece, with one draw2.

The only thing for it was a deciding rubber, to be played today, in Redruth3.

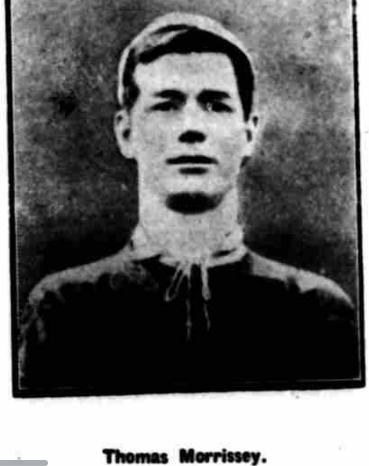

In front of a crowd of several thousands, Redruth went on to win, 6-0. Before he had even stepped on the pitch, Camborne’s big (6ft, 14st4), fiery enforcer-style forward, Tom Morrissey, was subjected to what we would term racist abuse. Though he was a miner from Beacon, his father hailed from Tipperary, and the Redruth faithful in the grandstand let him have it:

Morrissey, you _______ Irishman…

West Briton, April 29 1912

Such barracking was sustained throughout the game. Morrissey was only recently back from a two-week suspension for rough play5, and had been reported to the Cornwall RFU (CRFU) three times in the last four months, but he wouldn’t tolerate that. To the shock and horror of many, he bared his arse to the grandstand.

Female spectators left in disgust. A local man of the cloth vowed he’d never watch rugby in Redruth again.

The President of Redruth RFC, S. H. Lanyon, later stated that the heckling that day had been relatively unexceptional.

One of Morrissey’s team-mates was Sam Carter, a miner from Barripper who had worked in America and British Columbia. A talented forward with enough handling skills to pop up in the threequarters (he started life as a back), Carter had scored 16 tries for Camborne that season, and twice for Cornwall6.

Both Carter and Morrissey had turned out for Cornwall with Redruth’s John Menhennett, a USA-born miner from Four Lanes7.

However, that didn’t in any way make the three men friends.

Whilst allegedly gouging Morrissey’s eyes in a ruck (accounts vary), Menhennett was dragged to his feet by Carter. Menhennett then squared up to Carter, who teed off and got away one roundhouse above Menhennett’s eye that knocked him cold. (Menhennett would still be receiving treatment for the wound weeks later.)

The referee, W. Dennis Lawry, threatened to send Carter off the pitch. Carter, in the heat of the moment, told the official that

If you order me off, I will _______ half kill you.

Western Daily Mercury, April 22 1912, p3

He wisely (and rapidly) apologised for his remarks, and was allowed to play on.

But that wasn’t the end of it. After Lawry had blown no-side, Morrissey and Menhennett were still knocking lumps out of each other on the pitch, and were joined by several hundred fans in what deteriorated into a mass brawl.

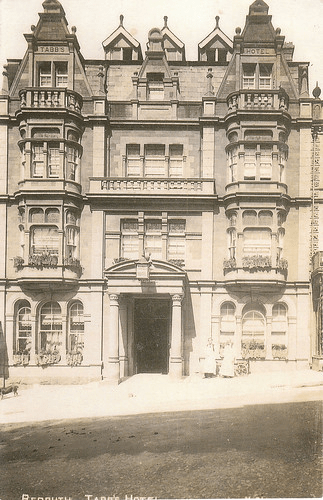

In those days, after a match both XVs would walk back to Tabbs Hotel on Fore Street to change, headed by Redruth Town Band.

Morrissey family legend maintains that Tom and another Camborne man (very possibly Carter, or a brother of Tom) walked back to Tabbs with their boots over their fists, daring anyone in the hostile, vocal crowd accompanying the teams to come ahead. They got no takers.

Redruth immediately cancelled the charity match that was to be held in Camborne the following Saturday.

W. Dennis Lawry, the referee, was a Penzance man. He was also Honorary Secretary of the CRFU8.

There was going to be trouble. In fact, Carter and Morrissey never played a game of Rugby Union again.

Kangaroo Court9

The verdict of the CRFU Committee on the behaviour of Carter, Morrissey and Menhennett was read at Tabbs Hotel, Redruth, on April 25.

From September 1 – the start of the 1912-13 season – Menhennett was given a one month ban. Carter, three months. Morrissey was not permitted to play rugby union for two whole years.

Even a member of the committee thought the sentencing drastic, if not draconian. That said, the judgements of the CRFU must be seen against a background of increasing instances of on-pitch violence and bad language prevalent in Cornish rugby, and Camborne-Redruth derbies were notorious in this regard. One commentator observed that

These are the best two Rugby teams in the county, and included in them are men who have donned the county colours with credit, but the rivalry between the two clubs has sometimes produced a feeling that does harm to sport, and the sooner this lesson is learnt the better it will be for Cornish Rugby Football.

‘Argus’, West Briton, April 29 1912, p2

There’s little doubt that the three players – Carter and Morrissey especially – were made examples of.

The prime mover in this was the CRFU’s Honorary Treasurer, Dr William Hichens (or Hitchins), formerly President of the CRFU from 1896-1905, and also President of Redruth RFC from 1893-190310. Indeed, the length of the bans were originally his motion.

Hichens so dominated proceedings one might be forgiven for thinking he was still President. The incumbent in 1912, Henry Vercoe, a Camborne man, is utterly silent in the reports11.

Hichens threatened resignation unless stern measures regarding the unsavoury events in Redruth were taken. At one point he admonished his colleagues for acting, in his enlightened opinion, like a bunch of women.

Suffice, Carter and Morrissey had few friends in the room. Those that were in their corner – Camborne’s President, Charles Bryant, and committeeman Albert Chenoweth - had little room to manoeuvre.

When Bryant attempted to suggest that the Redruth crowd’s barracking had provoked Morrissey to act as he did, Hichens slapped him down:

I am astonished, Mr Bryant. No provocation would justify the action of Morrissey.

West Briton, April 22 1912, p3

Lanyon, Redruth’s President, did in fact try and preach lenience regarding the subject of Morrissey’s gesture, but only on the grounds that he thought Morrissey was “uneducated”, and knew no better12.

This remark may tell you more about anti-Irish stereotyping than it ever will about the personalities of either Lanyon or Morrissey. Indeed, only a few years before the latter’s birth in 1889, the Camborne area was subject to vicious anti-Irish riots. Morrissey himself spent many a Saturday night brawling with those who sought to mock his roots13.

Let’s just say this: Lanyon was lucky that Morrissey wasn’t anywhere within earshot when he opened his mouth, and nobody questioned the mental faculties of those who had taunted him from the stands.

Carter, despite having a previously unblemished disciplinary record, would receive no reduction of his sentence either, despite Bryant’s pleas for forbearance.

Exasperated, Bryant moved that Carter’s and Morrissey’s bans be permitted, but only if a Redruth player recently reported for rough play received a similar duration of suspension. But Hichens held sway.

Chenoweth, outraged, said that

…the committee appeared to rule one team with an iron hand…Excuses were made for the conduct of any Redruth man, but when a Camborne man was before them…

West Briton, April 29 1912, p4

Chenoweth also moved to have the Redruth ground suspended, for provocation. It wasn’t seconded.

But there was further grist to Camborne’s mill. Bryant, on hearing how long his players were going to be out of the game, observed that they had been the very verdicts contained in rumours doing the rounds in Camborne, before the actual meeting.

Whether this is true or not, the ruling of the CRFU stood.

The immediate reaction of Camborne RFC was to cancel all fixtures with Redruth for the coming season14.

Neither Carter nor Morrissey bothered to attend their own hearing; hence the personal thoughts and reactions of both men are lost to us.

There’s little doubt, though, that they viewed the length of their suspensions as excessive in the extreme. If they wished to further their rugby careers – and they obviously had ambition to match their talent – there was really only one route open to them.

A recurring theme of the history of Rugby Union (and this post) is that, in the frequently heavy-handed enforcement of its own stringent regulations, the RFU (here represented by the CRFU) inadvertently pushed its own players toward the Northern Union (NU)15. Such a thing was to happen in the case of Sam Carter and Tom Morrissey.

It’s possible they may have been considering (or negotiating) the option before the events of April 1912. But, over the summer, either they approached the Northern Union, or the NU collared them.

Carter and Morrissey eventually signed contracts with the NU’s Rochdale Hornets. Miners no longer, they were now professional sportsmen. Both men, Morrissey with a young wife in tow, arrived in Rochdale on Wednesday, September 4, 191216.

The CRFU had given them both a two-fingered salute; Carter and Morrissey gave the CRFU – and by extension, the RFU – one in return. The draconian suspensions handed to them by the CRFU essentially put them on the train north, into the hands of the NU.

Sam and Tom knew there was no going back. As the RFU’s Bye-Laws and Laws of the Game for the 1911-12 season made quite clear,

Professionalism is illegal.

p75

One of the myriad acts of professionalism as defined by the RFU was “signing any form of the Northern Union”, the consequences of which would see you

…expelled from all English clubs playing Rugby Football, and [you] shall not be eligible for re-election or election to any club.

p78-81. Courtesy of the RFU Museum, Twickenham

Sam and Tom had utterly burned their bridges. They knew they could never play Rugby Union again, join or visit an RFU Club, or speak to a Rugby Union player. They may not even see Cornwall again. But they had done it on their own terms.

Camborne RFC, seething with the CRFU at the senseless loss of two star players, very nearly declared for the NU as well.

Cornish codebreakers and veiled professionals

You won’t find much on Morrissey, Carter or others like them in official histories of Cornish rugby. Both men are very briefly mentioned in Camborne RFC’s standard history, in a list of players capped for Cornwall18. Abandon the RFU for the NU and, Soviet-style, you were written out of history.

From the moment the NU splintered from the RFU in 1895 (and just why this happened need not concern us here19), the latter’s Secretary, Rowland Hill, decreed that

…no club belonging to our Union will be permitted to play matches with any club which is in membership with the Northern Union.

Qtd in Lake’s Falmouth Packet, September 14 1895, p320

From the get-go, then, the NU, its clubs and its players were “outside the pale of Rugby football”21.

The RFU cultivated a rigidly amateur, public school persona in the early 1900s, whereas the NU projected an image of not caring how you spoke or where you came from. How you played was what mattered, and the game was played by working-class men, and run, by and large, by men with similar backgrounds. Furthermore, if you played under the auspices of the NU, generally speaking, you got paid.

By the time Sam and Tom signed with Rochdale Hornets, the NU was a fully professional organisation. Already, it had evolved into the game of ‘Rugby League’ that we recognise today. Professional teams from the Antipodes, playing under NU rules, had already toured the North, and the NU, in return, sent a representative side Down Under22.

The NU’s clubs were replete with talent scouts and agents. They targeted players from the Westcountry, particularly labouring men and miners24.

The explanation for this is obvious. The RFU’s County Championship, then the yardstick of the country’s Union talent, was dominated by Westcountry XVs from the years 1901-191325. This made the region a priority for NU recruitment, and throughout the history of Rugby League its officials have always attempted to prise working men away from their communities:

…usually it’s a working-class type of fella who takes the bait – or makes the right decision…

Unidentified Rugby League representative, The Rugby Codebreakers, BBC documentary, 2018

Playing sport for prizes – or cash rewards – had long been a feature of working class culture26. The notion of going to where you would get the best return for your efforts and talent was reinforced in Cornwall by the tradition of the ‘tribute’ mining system, where miners would negotiate the terms of their contract with the Captains. Add to this the history of Cornish migration in the face of economic hardship, and it’s easy to understand why Cornwall nurtured, and even sympathised with men who went North to seek their fortunes on the playing field27.

And Cornish rugby was a working-class game. Though admittedly a small sample, look again at the Camborne side of 1910-11:

Of the players’ occupations that I’ve been able to trace, seven were miners (both Lovelocks, Mills, Eustice, Morrissey, Carter and Stephens), and two (Lance, Bath) were engineers or fitters. Of the management, only the President, Charles Bryant, had a middle-class occupation, that of Bank Manager. John Buddle was an explosives agent, Albert Chenoweth a painter/decorator, and William Trounson a carpenter28.

Carter and Morrissey didn’t need to look far for inspiration to join the NU either. In August 1911, their team-mate, Plymouth-born Cornwall full-back Harry Launce, signed for Salford. Launce lived to be 80, his 40-year involvement with the amateur Langworthy Reds club in Salford memorialised annually with a game played for The Harry Launce Memorial Trophy29.

The NU’s agents, or “poachers” for “players of note” were at work in Cornwall from as early as 190031. In 1920 one poacher had a real coup in signing the Redruth and Cornwall star forward Tommy Harris to Rochdale Hornets for £300 (that’s £11K today). He and Sam Carter would play together32. What the Cornish rivalry meant to both men whilst in Lancashire is anyone’s guess.

Although the official RFU policy toward such men was to banish them forever, the reaction of Cornish people to those who signed with the NU could be summarised thus:

Good luck…

Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 30 1900, p7. A Penzance player called Triggs had signed for Rochdale

One might add, ‘and well done’. William Trembath, a Newlyn man who also joined Rochdale, had an interview published in a Cornish ‘paper, the tone of which was overwhelmingly positive34. Tommy Harris’ selection for the England Rugby League team was noted with pride35. When Sam Carter married a Rochdale girl, Bessie Winnard, in 1914, it was written that the

…event will be received with much gratification by his numerous sporting friends in Camborne.

Cornish Telegraph, June 4 1914, p3

Even post World War II, both Carter and Morrissey were noted as “fine players” in both codes, with Carter being described as “magnificent”36.

No doubt, many a Cornish rugby club will have stories of those who ‘went away’, and it’s important to remember that the players I’ve described here are the high-profile signings. How many miners with a love of sport left Cornwall to work in the northern collieries, and found themselves playing Rugby League?

People in Camborne must have regretted the departure of Sam Carter and Tom Morrissey, but they would have understood why they left.

I mean, imagine the furore if they’d done the unthinkable and signed for Redruth…37

Quality rugby players in the Westcountry, then, were a much sought-after commodity – on both sides of the game’s divide. Union clubs knowingly broke their own governing body’s laws on professionalism to keep their teams’ sweet, and to lure a big name into their fold.

As far back as 1899 Torquay Athletic were suspended for offering players a financial incentive to sign on39. In 1907 an RFU Commission was investigating charges of professionalism against Devonport Albion and Plymouth RFC, with evidence helpfully provided by representatives of the NU – covert NU policy being to sow discontent in the ranks of the RFU40.

The transfers of two of Cornwall’s 1908 County Championship XV, John Jackett (Falmouth to Leicester), and James ‘Maffer’ Davey (Redruth to Coventry), were always viewed cynically41. Jackett and his new club were exonerated after an investigation, but the verdict caused the President of the RFU, C. A. Crane, to resign in disgust42. Coventry had been discovered paying Davey’s lavish hotel bills when he stayed in their town, and both were suspended in 190943.

It’s important to remember that ‘veiled professionalism’, as it was known, was possibly more widespread than these investigations suggest. How many clubs managed to cook their books so effectively the RFU commissioners found nothing? How many RFU commissioners forgot their holier-than-thou principles when a burly clubman quietly offered them some ‘boot money’ of their own? That said, would any club be foolish enough to risk bribing the RFU’s Untouchables?

Sam Carter and Tom Morrissey, therefore, were two of many. It’s rather ironic that, as they were making their preparations to leave, it looked as if Camborne were going to commit to the NU game.

Rugby’s Kerry Packer?

Plymouth man Edwin Henry Searle had a vision, and he wanted to make money – maybe making money was his vision. He succeeded in acquiring wealth; on his death in 1927 he left £914, or £47K today. This was certainly a worthy effort for a humble commercial traveller, the kind of man George Orwell identified as being condemned to a thankless life of transient door-to-door drudgery46.

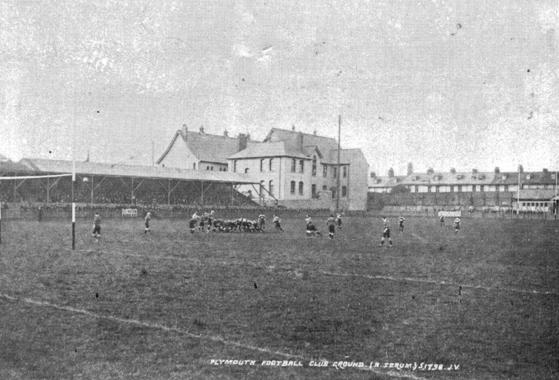

Searle was also Hon. Secretary of the Plymouth Grounds and Stands Company, which owned South Devon Place – the home of Plymouth RFC.

The company had a problem: Plymouth RFC wasn’t paying48. Falling attendances due to the success of Devonport Albion RFC and Plymouth Argyle FC had saddled the club with debts it couldn’t pay. In April 1912 the Devon RFU (DRU) gave them two weeks to cough up, or face suspension.

The Plymouth Grounds and Stands Company decided to abandon Plymouth RFC, and the club folded that summer49.

Not wanting to lease their ground to a club that was broke, Searle and his cohorts had started to look elsewhere to put bums back on seats, and cash in their coffers. They needed as big a draw as soccer, they needed novelty, and they needed spectacle. They wanted something they thought was better than Rugby Union. They wanted

Brighter and more spectacular football.

Gloucestershire Chronicle, August 17 1912, p9

They wanted the Northern Union. Now they had to convince the Westcountry that it wanted the NU, and the NU that it wanted the Westcountry.

In late April 1912 a “well-known Plymouthian” travelled to an NU conference in Manchester, the result of which was

…said to have completely paved the way for the introduction of professional Rugby in the West.

Western Daily Mercury, April 22 1912, p3

The Plymouth man, though unnamed, must have been Searle – he was a travelling salesman, after all. Doubtless he talked big when given the opportunity – he may have even fed the above line to the Press – and the NU decided to take a gamble.

The NU, for their part, must have been overjoyed. It was a win-win situation. If Searle & Co could establish a pro ‘Western League’ under Northern Union rules, they (the NU) would have a toehold in the region and opportunity for expansion. If it all came to naught, the RFU would doubtless suspend or expel any player associated with the movement, who would then be compelled to travel north for their rugby.

For the time being, then, everyone conveniently forgot that Plymouth was a helluva long way from Wigan, or Hull.

On Saturday May 11 1912, 10,000 people filled South Devon Place to watch an NU exhibition match between Oldham and Huddersfield, the latter winning 31-26. Searle and the other owners of the ground must have been grinning behind their cigars. 10,000 was easily their biggest gate all season51.

By July, it was announced that South Devon Place had been acquired by an NU club, which was in fact the hastily-formed Plymouth NU club. It goes without saying that the Plymouth Grounds and Stands Company would have done well out of this arrangement. Indeed, Searle was on the committee of the new club52.

It was looking promising. But there was one big obstacle: they only had one team, Plymouth, and probably very few players. The NU’s secretary, Joseph Platt, had stipulated twelve Westcountry clubs to constitute a league. Get twelve teams, and the NU would give them prized Welsh asset Ebbw Vale.

From his home on Grafton Road, Searle cast his net. He didn’t merely write to twelve clubs pitching his big idea, he probably wrote to every club of note in the Westcountry.

Searle’s definition of ‘Westcountry’ was incredibly inclusive. Cinderford, up in the Forest of Dean, received (and publicly repudiated) his missive54. Likewise Bath RFC, who wanted to avoid an investigation by the RFU for allegedly associating with the NU. The “letter shall lie on the table”, Bath announced, and the Club, rather fawningly,

…had no idea of forsaking its loyal allegiance to the Rugby Union.

Bath Chronicle, August 17 1912, p7

All of which begs the question: did Camborne receive a letter? Alas, the committee minutes for the 1911-12 season do not survive but, as a premier Cornish club, and one known to be discontented (to say the least) with its own Union, it’s inconceivable that Searle didn’t write to them.

Camborne were certainly linked to the movement from an early stage, as were Redruth and, later, Falmouth55. That said, every senior club in the Westcountry was associated with the movement at one time or another, mainly because Searle contacted them all. As with the ‘Rebel’ Cricket Tours to South Africa in the 1980s, you never knew for sure who was going until they stepped aboard the plane.

Redruth opted out early. So did Devonport Albion, who described the whole affair as “utterly impracticable”56.

And Camborne? W. Dennis Lawry, Hon. Secretary of the CRFU, had sounded out an “official” of Camborne RFC. Any notion that the club was going over, stated Lawry,

…is not true.

Western Echo, July 27 1912, p2

Camborne, Lawry was assured, were ploughing forward with the forthcoming Union season.

We can accept the Camborne official’s statements to Lawry at face-value. Or, we can bear in mind the RFU’s tough policy on clubs known to be flirting with the NU, and recall that Lawry had refereed the fateful match that saw Carter and Morrissey suspended.

Of course the official was going to deny all knowledge, especially to a representative of the CRFU. The Press weren’t overly convinced:

…those who have a strong feeling against the Cornish Union would favour the introduction of the Northern Union or any other game.

West Briton, July 29 1912, p3

Camborne fit the bill perfectly. One resident stated that everyone in the town was

…yearning for the new code.

Western Evening Herald, December 7 1912, p4

Friday August 30, 1912, may have been one of the biggest dates in the history of Camborne RFC. The club was “unofficially represented”57 at a meeting of the NU movement in Newton Abbot. Also present were men from Plymouth and Torquay, and doubtless several other clubs. It was tense.

Camborne – and any other Cornish teams present – needed the Devon clubs to go over. Devon needed Cornwall. Torquay wouldn’t commit unless Newton Abbot did so first.

And Newton Abbot did commit. The Western League was on. Cheroots were lit. Pipes stuffed. Trebles all round. The hawks in the room wanted the movement made public there and then.

Suddenly, it was all off again. Newton Abbot did a complete volte face; the promoters (Searle and Co) had only managed to secure six teams, too small a number to constitute a league.

Camborne chivvied Torquay to force the issue, but it was all for naught. Ultimately the movement was too small, and the clubs too mistrusting of each other, to make it a reality.

Searle didn’t have the network, the force of character, or the bank balance, of Kerry Packer58.

Then the Union backlash began.

The Purge

Firstly, Camborne were in a parlous financial state, despite a slim profit for the 1911-12 season of £35 (£3,000 today). A demand from the CRFU in the form of a letter that they cease issuing cheques was ignored. No fixtures with Redruth had been arranged for the 1912-13 season, which meant a big loss in revenue. As the committee minutes held at Kresen Kernow make clear, it wasn’t until April 1913 that Camborne were prepared to open talks with Redruth.

It was agreed that the 1912-13 programme be run with a reduced fixture list, on a tight budget. Now was not the time to commit to the NU59.

On Saturday September 21st, the DRU summoned a number of officials from Devon clubs (Plymouth, Brixham, Torquay, Teignmouth and Newton Abbot) to the Globe Hotel in Newton Abbot. The DRU then suspended seven of them, without hearing, for their involvement with the NU.

But the seven men, with Searle in an observatory/inflammatory role, wouldn’t go quietly. As one historian has observed,

Rather than ‘throttling the hydra’ of professionalism, the RFU found that severing one head had only resulted in the creation of more.

James W. Martens, “They Stooped to Conquer: Rugby Union Football, 1895-1914”, in Journal of Sport History 20:1 (1993), p30

So it proved here. Searle produced a letter from Arthur Havill, the Exeter skipper, expressing interest in recruiting for the Westcountry movement. Searle’s intimation was that the DRU ought to be investigating more.

A. E. Bryant, one of the seven and a key figure in the nascent Plymouth NU club (see the image above), went further. He condemned the actions of the DRU Secretary, T. Stanley Kelly. Kelly, an Exeter man, had met with the NU reps too and, like Havill, had given the impression that his old club was all for switching. In fact, Kelly had been gathering information for the DRU all along. Bryant’s verdict on the public-school, former Harlequins and England captain was the most damaging that any gentleman amateur could bear. Kelly was

…unsportsmanlike…

Western Daily Mercury, September 23 1912, p3

Bryant then went public with more accusations of payments made to players by several Devon clubs, including weekly wages and win bonuses, urging the RFU to put their own house in order62.

Bryant’s call to expose the allegedly rampant ‘shamateurism’ in the Union game put the RFU in an invidious position. Do nothing, and they would be hoisted by their own clubs’ hypocrisy. Yet if they acted and found Bryant’s case carried weight, the inevitable suspensions would play into the NU’s hands.

Put another way, Bryant had the RFU by the balls. One man present at The Globe that day predicted that

…Northern Unionism would be established within a month.

Western Daily Mercury, September 23 1912, p3

The RFU decided to come down heavily. By October a commission, headed by RFU President A. M. Crook, was ensconced at the Rougemont, Exeter. There was a Press blackout. The investigation was deemed to be “the most important of its kind”64.

Besides upholding the suspensions made by the DRU, the RFU summoned W. Dennis Lawry of the CRFU to provide that Union’s accounts. Ditto T. Stanley Kelly for the DRU. Evidence needed to be sifted. Witnesses sought.

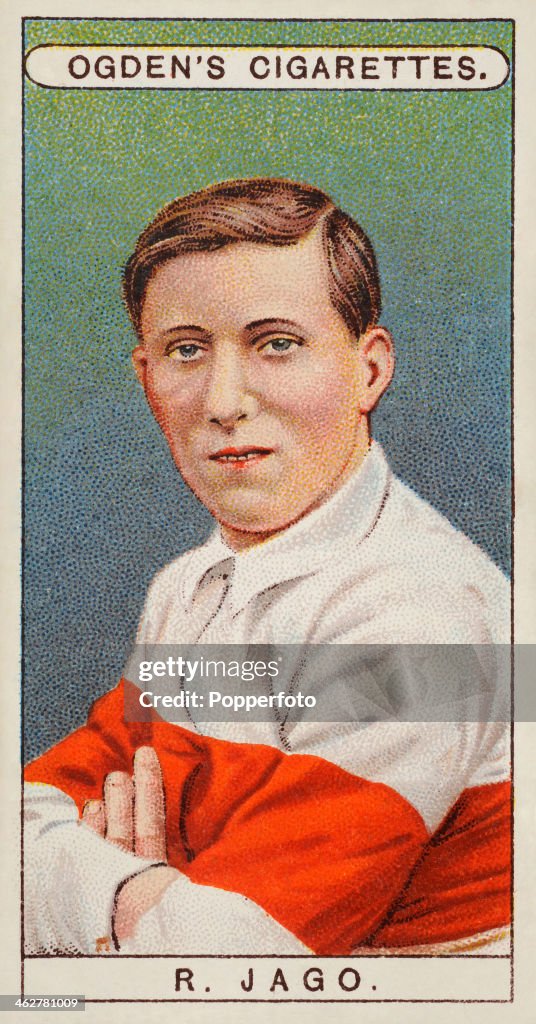

Exeter were exonerated. Torquay Athletic were suspended, as were practically all of Devonport Albion’s 1st XV. This latter included a Cornishman, Fred Gilbert, and a Devon and England scrum-half who had begun his career at Falmouth, Raphael Jago. In all, 23 officials were suspended, and 17 players65.

The RFU didn’t conclude its investigations into the CRFU and its clubs until June 1913. After digging as far back as 1901-2, the commission found…nothing.

The RFU then charged the CRFU £40 expenses (£3,800 today) for the privilege66.

Opinion was divided on the RFU’s actions. One ‘paper called it “the finest step that could have been taken for rugby in Devonshire”67. Another reckoned that

…the commission…has played into the hands of the Northern Union disciples.

Cornish Echo, December 6 1912, p7

As the Echo had feared, the Western League decided to grimly battle on. Coventry played Plymouth under NU rules at South Devon Place on Christmas Day 191268, but overall the movement was a failure.

Five clubs (Plymouth, Teignmouth, Paignton, Torquay (NU, that is, Torquay Athletic remained separate) and Newton Abbot) stubbornly played a few NU matches. Attendances were poor, and players thin on the ground. Torquay had to make up numbers for one match by filching men from their fellow NU teams69.

Camborne, even at this stage, were approached. Torquay wrote to them in early 1913 requesting fixtures in the new code, but the committee decided that, this time, they

…could not entertain their proposals.

Minutes and Team Selections, Camborne Rugby Club, 1912-1915. Kresen Kernow, ref: X1280/1/2

Although Plymouth and Torquay also entertained St Helens, and England NU played Wales at South Devon Place before 7,000 in February 1913, it was all over by April.

The Plymouth NU committee, Searle included, resigned that April. South Devon Place was put up for let. The NU, it was written, had been “cracked” in the Westcountry71. Its players went north, or faded away.

For a few, short, tantalising months, the history of Rugby in Devon and Cornwall looked very different. Northern Union/Rugby League wasn’t seen again in the Westcountry until 1947, when Leigh and Barrow played a series of exhibition matches72.

In the meantime, Sam Carter and Tom Morrissey were making their marks for Rochdale Hornets. A Rugby League historian believes both men held fire on moving north until Camborne’s non-involvement with the Western League became a certainty, but makes no mention of their suspensions in April 1912. It’s more likely they began canvassing for Northern Union interest shortly after their harsh sentences were passed. The NU actually paid lip-service to one of its own bylaws in requesting of the CRFU information on why they had been suspended, but true to form the CRFU ignored it. One gets the impression that, throughout 1912 and early 1913, masses of letters sat on various committee room tables, never to be acknowledged73.

The Hornets’ new signings were free to play…

Ginger Morrissey

There’s a question every young sportsperson must ask themselves when they first turn professional, and that question goes something like:

What if I don’t make it?

It’s a shame to write, but Tom Morrissey didn’t make it – largely through no fault of his own.

The Hornets made quite a fuss of his and Carter’s signing. Like prominent Americans defecting to the USSR, it was a propaganda coup. Of Morrissey it was written that he

…is a big, lusty fellow, who should make his mark in the Northern Union game…He has a splendid reputation as a scrimmager in the West Country.

Rochdale Times, September 4 1912, p7

His height, weight (at 14st, it was noted that he would be heftiest in the Hornets’ squad74) and ginger hair would make him an instant hit with the fans, not to mention his aggressive, in-your-face style.

But it didn’t quite work out like that. Getting capped for Cornwall was easier than getting a regular slot for Rochdale’s Chiefs.

Tom’s appearances until spring 1914, by and large, were limited to the ‘A’ team. He couldn’t quite force his way up to the top level. Whenever he did get a chance, such as over Christmas 1912 when Rochdale pulled off a shock victory over St Helens, he didn’t exactly cover himself in glory.

In that particular match, his old Camborne pal Sam Carter scored a nifty try; Tom himself knocked on at a crucial moment75.

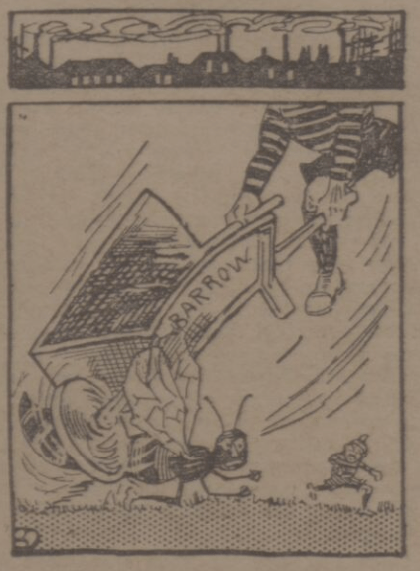

While Sam flourished, Tom languished in the ‘As’76. A chance came in February 1914. A good performance for the ‘As’ against St Helens put him in the running. Hornets Chiefs, having lost heavily on the same day to Barrow, were short for the next game at home to Dewsbury. Tom got the nod. He had to make the most of it77.

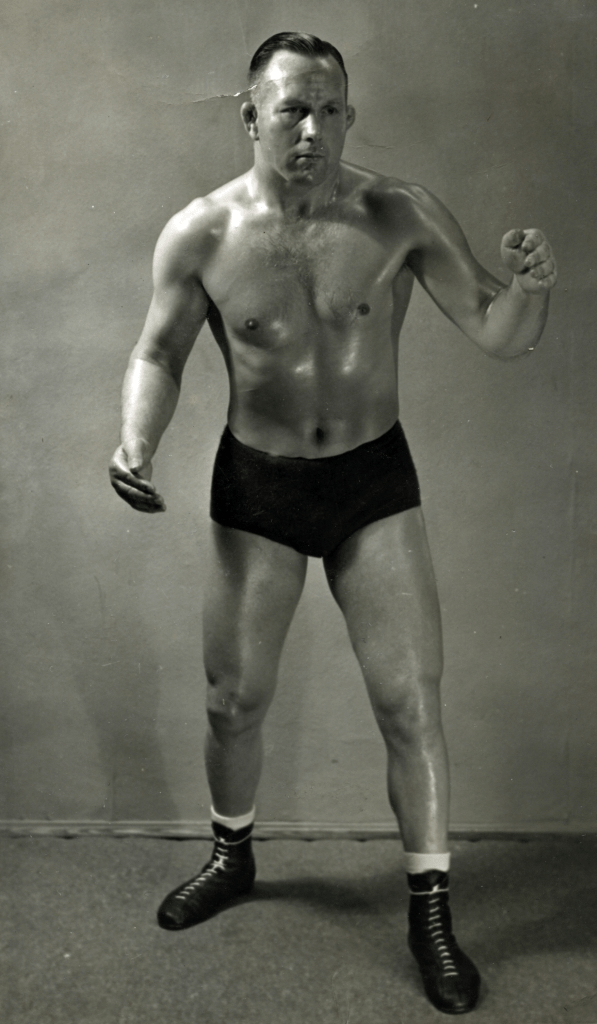

8,000 spectators turned up to watch what must have been one of the worst games of professional rugby in history, if the reports are to be trusted78. A nil-nil draw left the Hornets’ faithful looking very much like the irate gentleman below:

Although Dewsbury lost a player on account of him having some ribs broken, the game is noteworthy for its significance in the story of Tom Morrissey. It was the last game of rugby he ever played.

A knee injury sustained in the match via an opponent’s stud became violently inflamed. Septic poisoning had set in, and Tom required an emergency operation:

…it is a question whether Morrissey will be able to play for a considerable time.

Rochdale Times, March 4 1914, p7

Family history maintains that the presence of arsenic in a weedkiller infected Tom’s knee. Whatever the cause, he was desperately unlucky. The leg was left permanently stiff.

For a time, he remained in the Hornets’ fold, organising and selling match programmes. By 1939, he and his wife, Rita, were living in Moss Street, Rochdale, and Tom was an iron driller with Petrie and McNaught, a job he had been holding since at least 192179.

He visited Cornwall in 1950, and is remembered as a big, yet quietly spoken man.

Tom Morrissey died in 1953, aged 6480.

Tom’s rugby career is a classic case of what might have been, on two counts. With the Northern Union, had he secured a regular first team berth, glory awaited. Had he remained in Union, his size, ability up-front and reputation suggest he could have been spoken of today in the same breath as the likes of Camborne and Cornwall legends Gary Harris, Paul Ranford or Chris Durant.

Get Carter

Sam Carter made it. A forward who fancied himself as a threequarter was an object of derision in Cornish rugby81, but a man with skill and versatility was a welcome asset for Rochdale Hornets.

Carter became a back-row forward in NU, but that was only a starting-point. He could deputise on the wing, at least in his early years82. He could scrum. He could tackle. He could pass. He could dribble – an important facet of the game in those days. He had vision. What’s more, he could make it difficult for the opposition. Even late in his career, the man replacing him in a match was judged

…not equal to Carter as a breaker-up and worrier.

Rochdale Times, May 7 1919, p4

A player-profile of the time said he was

…one of the finest loose-forwards…Quick away from the scrums (as visiting half-backs know to their cost)…always quick to sense an opening, often combines with the backs and is a consistent try-getter.

Courtesy Rochdale Hornets Heritage Archive

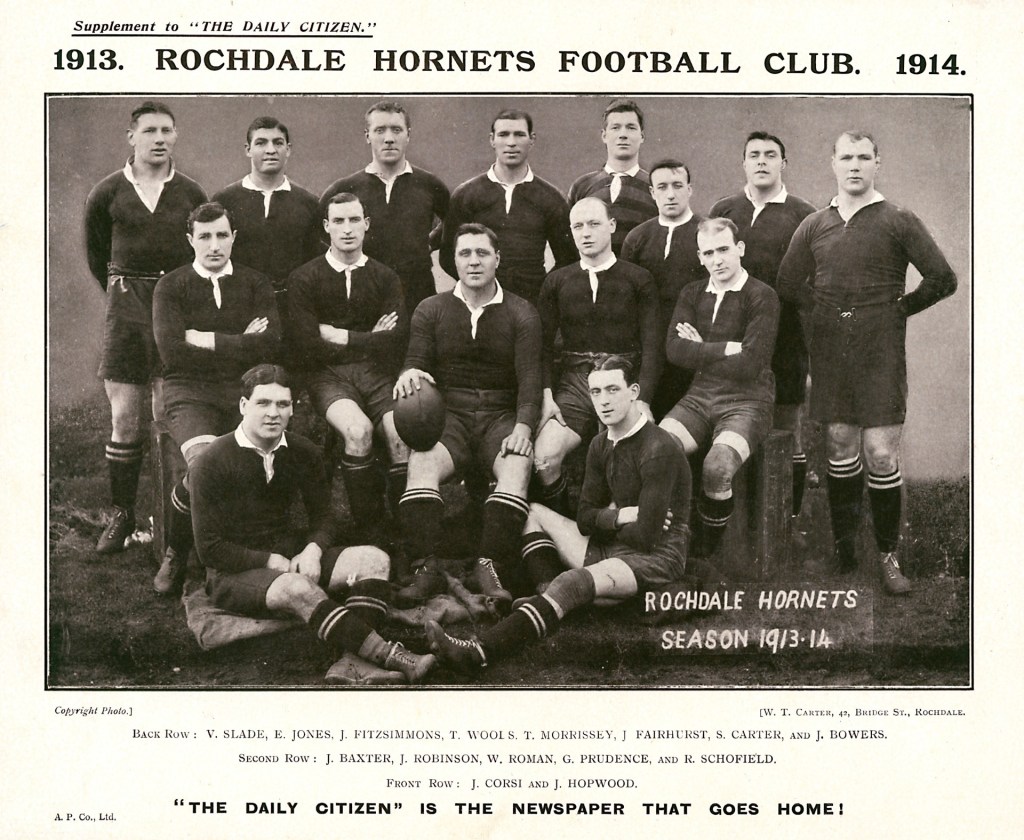

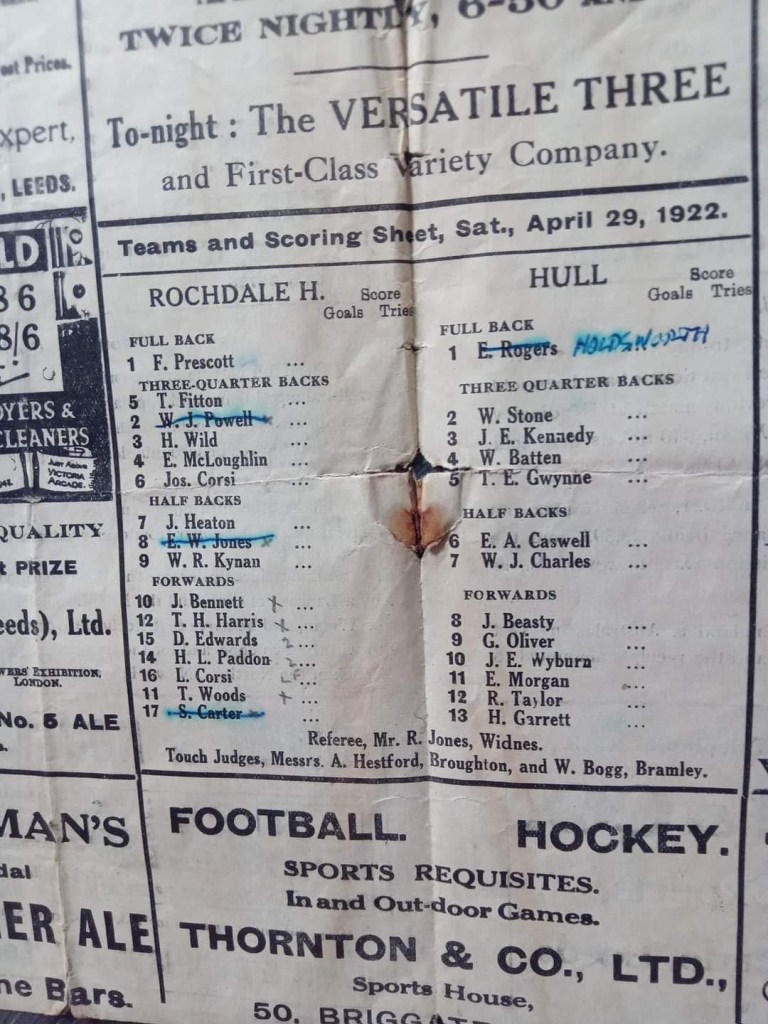

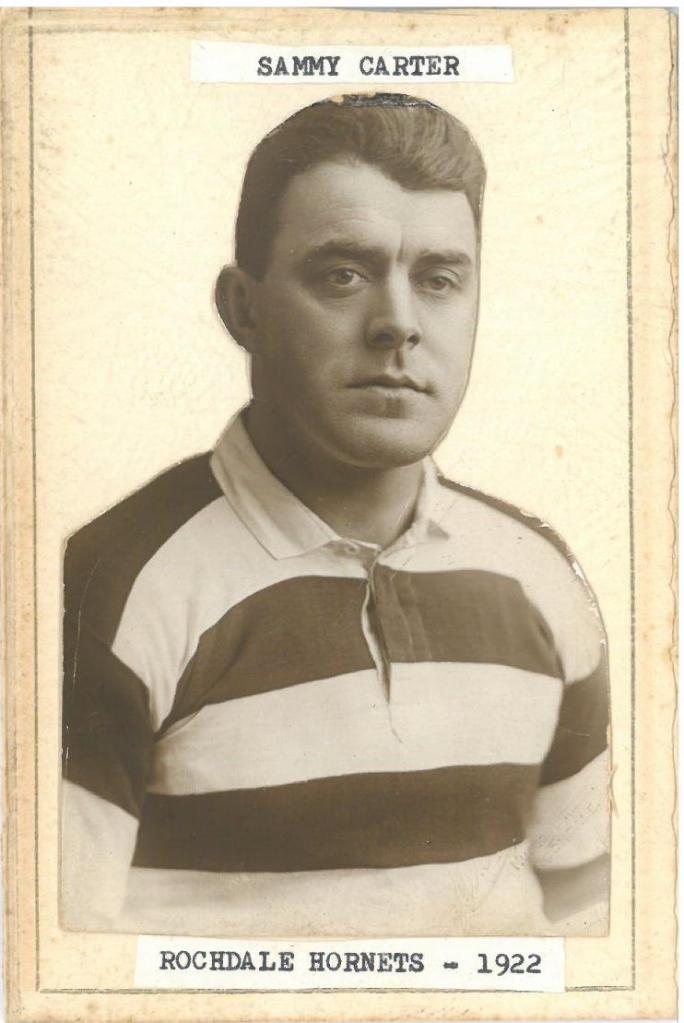

During what was probably his peak season, 1913-14, he played 38 of 39 fixtures for the Hornets, and was in with a shout of international recognition, if the illustration above is any yardstick83.

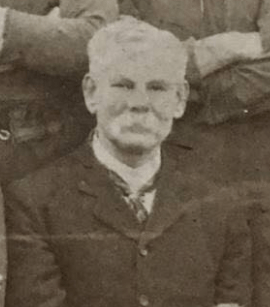

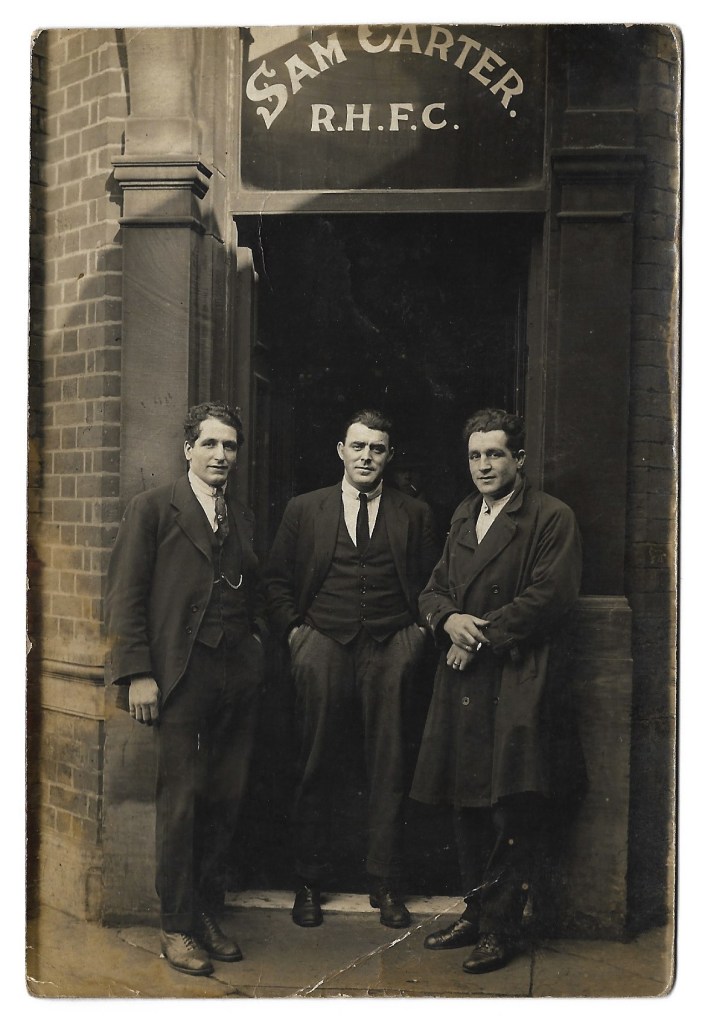

Sam is standing, second from the right. Note the broad shoulders, bull neck and lantern jaw – a player in his prime. To his right is Tom Morrissey, in his final season of rugby.

Had international NU matches continued despite the war, it’s arguable that Sam would have been capped by England, such was his form. But here, he was unfortunate84.

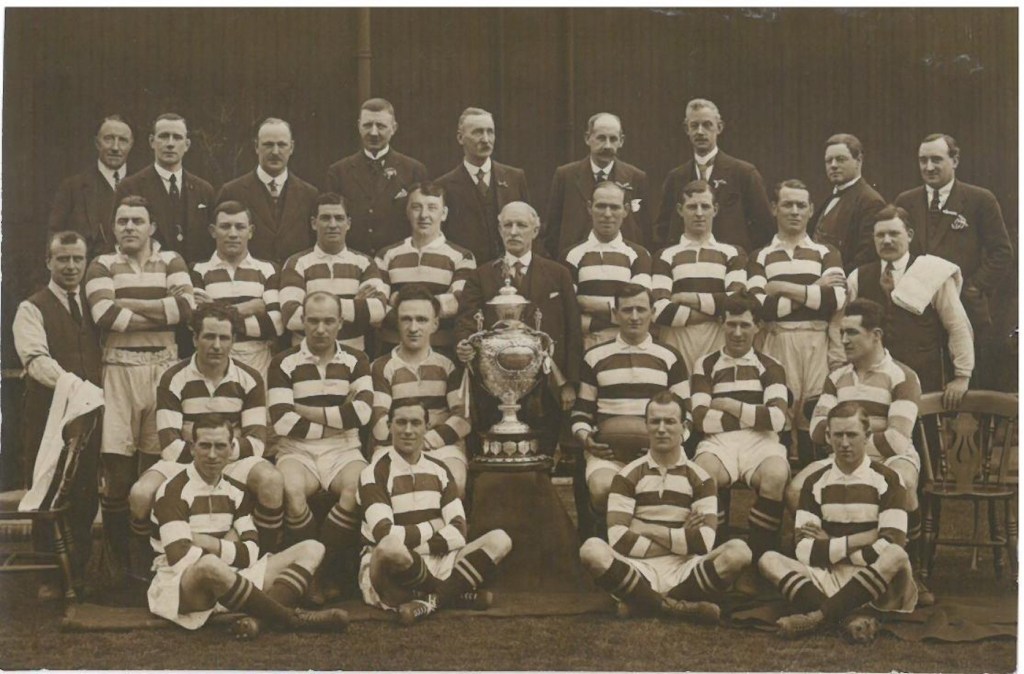

By the time the Hornets won their first (and to date, only) Challenge Cup in 1922, Sam was 34 and past his best.

However, he was still part of the squad, and played two of the five games of Rochdale’s campaign. This included a 54-2 mauling of Broughton Moor in the first round, and an eyewateringly tight 5-2 quarter-final win over Oldham. This last saw a record gate for a Hornets match – 26,50085.

But, for the crunch games, younger and faster men were preferred, such as Tommy Harris and the Cardiff-born Corsi brothers. Before the final versus Hull at Headingley, the Rochdale Times ran profiles of the Hornets’ squad. Sam was described as a versatile player, being

…the safest with his hands of any of the forwards. Has an old head on him which stands him in good stead.

April 26 1922, p7

‘Old head’ sounds worryingly close to ‘veteran’. Sam (like Tom) missed out on Hornets’ glorious – and narrow – 10-9 victory in front of 35,000 spectators86.

To be honest, by 1922 Sam was perhaps thinking about life beyond rugby; indeed, he only played 19 games that season87. The 1921 Census tells us he was already landlord of the (now long demolished) Golden Fleece on Oldham Road.

Sam, as noted earlier, wasn’t lacking ambition. As he himself said,

…Rochdale had been good to him, and it was his desire to do something for the town of his adoption.

Rochdale Observer, October 26 1932, p4

Thus in 1932 he stood as the Conservative candidate for Rochdale’s Castleton East district. His qualifications were drawn from

…the school of experience, and he considered that that experience fitted him to represent a working class ward.

Rochdale Observer, October 26 1932, p4

He wanted improved hospital services, clean streets, better housing, public baths and unemployment schemes. He opposed the unpopular Means Test88 as a tool for men who

…made the misfortunes of the unemployed an excuse for reaping political advantage.

Rochdale Observer, October 29 1932, p6

He lost. Though an immensely popular man with his heart in the right place, politics was perhaps not his game, and Depression-era Rochdale, with 10,000 cotton operatives on strike, not the easiest place to embark on such a career89.

A Hornets player-profile noted that Sam was “a general favourite and no wonder”:

…he is a thorough gentleman…Another characteristic is his cheerfulness…

Courtesy Rochdale Hornets Heritage Archive

Sam’s character was put to the test. The 1939 Register notes that he and Bessie were both unemployed, and living in Buersil Avenue. Maybe the time had come for him to return to Cornwall. After all, as of one of an astounding thirty-two siblings, Sam would have plenty of support in the Westcountry90.

The Carters took up residence in Treswithian Road, Camborne – the house was named ‘Buersil’. Though out of work in Rochdale, they must have been comfortable. Sam’s estate on his death in 1967 was valued at £4794 (£73K today). Bessie followed him in 198091.

Did Sam ever visit his old Union club? Officially, as a one-time professional, he would have been barred and, knowing this, he probably stayed away. Certainly nobody I’ve spoken to from those times remembers him, though a younger brother, James, was a regular spectator.

An old man deserved better, especially one who, to the best of my knowledge, remains the only Camborne player to be capped for Cornwall and win the Rugby League Challenge Cup.

With special thanks to Jim Stringer of the Rochdale Hornets Heritage Archive, Professor Tony Collins, Adrian Wallace (a relative of Sam Carter), and Jean Charman and Reg Bennett (relatives of Tom Morrissey).

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- See my posts on the rivalry here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/09/02/camborneredruth-the-oldest-continual-rugby-fixture-in-the-world-part-one/

- The Cornish Post and Mining News (April 4 1912, p7) gives it to Redruth. The Cornish Echo (March 15, 1912, p6), plumps for Camborne. Certainly Redruth’s playing record that season was formidable: P30, W24, D3, L3, F518, A79 (Cornish Post and Mining News, April 18 1912, p7). Camborne believed they’d won it at a meeting in September (West Briton, September 12 1912, p5).

- The main narrative for this section, unless otherwise stated, is from reports in the following newspapers: Royal Cornwall Gazette, April 18 1912, p3; Cornish Post and Mining News, April 18 1912, p7; Western Daily Mercury, April 22 1912, p3; West Briton, April 22 1912, p3, April 29 1912, p4; Cornishman, May 2 1912, p3; Lake’s Falmouth Packet, May 3 1912, p6. The biographical details of Morrissey, Carter and Menhennett, unless otherwise stated, are from the 1911 Census.

- On signing for Rochdale Hornets, Morrissey’s and Carter’s vital stats were recorded. For the record, Carter was 5ft 9″ and 12st 7lbs. Rochdale Times, September 4 1912, p7. The team photograph that heads this section illustrates how big, for the time, Morrissey was.

- Noted in the Cornishman, March 29 1912, p3.

- From the Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 16 1911, p10, and the Rochdale Times, September 4 1912, p7. Carter’s working overseas is mentioned in Lake’s Falmouth Packet, September 6 1912, p2. Jim Stringer of the Rochdale Hornets Heritage Committee informs me that Sam worked in Bute City and Idaho, and that his earliest playing position in Union was fullback.

- The three men’s involvement with Cornwall is noted in the Western Times, November 16 1910, p3, and the Western Echo, October 22 1910, p4.

- Lawry’s Penzance connections are noted in the Western Echo, November 30 1907, p3. For a list of past and present officials of the CRFU, see: https://www.crfu.co.uk/home/officers-patrons/

- As previously, the main narrative for this section, unless otherwise stated, is from reports in the following newspapers: Royal Cornwall Gazette, April 18 1912, p3; Cornish Post and Mining News, April 18 1912, p7; Western Daily Mercury, April 22 1912, p3; West Briton, April 22 1912, p3, April 29 1912, p4; Cornishman, May 2 1912, p3; Lake’s Falmouth Packet, May 3 1912, p6.

- For a list of past and present officials of the CRFU, see: https://www.crfu.co.uk/home/officers-patrons/

- For Vercoe’s connections to Camborne, see: Western Echo, July 5 1913, p3.

- Cornishman, May 2 1912, p3.

- For the riots, see: Louise Miskell, “Irish Immigrants in Cornwall: the Camborne Experience, 1861-1882”, in Roger Swift and Sheridan Gilley (eds.), The Irish in Victorian Britain: the Local Dimension, Four Courts Press, 1999, p31-51. Morrissey’s family maintain he retaliated swiftly to any expressions of prejudice as regards his Irishness. Certainly he was arrested and fined for fighting on more than one occasion. See: Cornishman, December 31 1908, p5.

- Noted in the Cornish Post and Mining News, July 4 1912, p5.

- Regarding the suspension of both men, the CRFU and the RFU were complicit. Camborne RFC appealed to the RFU, but the original ruling was upheld. See the West Briton, May 23 1912, p7.

- Morrissey had married Rita Tonkin in Camborne earlier that summer. England & Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index, 1837-1915, 5c, 314. Their arrival was noted in the Rochdale Times, September 4 1912, p7.

- See: https://cornwallrlfc.co.uk/news/graham-paul-the-cornish-express/, and https://hullkr.co.uk/graham-paul-calls-it-a-day/

- For example, The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall, by Tom Salmon, CRFU, 1983, or Rugby in the Duchy: An Official History of the Game in Cornwall, by Kenneth Pelmear, CRFU, 1959, and The Story of a Proud Club: Camborne RFC Centenary Programme 1878-1978, by Philip Rule and Alan Thomas, 1977.

- Those wanting to know why there are two different forms of Rugby Football are directed to the following books by Tony Collins: Rugby’s Great Split: Class, Culture and the Origins of Rugby League Football, Frank Cass, 1998, and A Social History of English Rugby Union, Routledge, 2009, p29-47.

- For a brief overview of Hill’s career, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Rowland_Hill

- As observed in Lake’s Falmouth Packet, September 14 1895, p3.

- See Tony Collins, Rugby’s Great Split, p196-230. The only aspect missing from the modern game of Rugby League was limiting the number of tackles a team in possession of the ball could have. Four tackles was introduced in 1966, and six in 1971. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laws_of_rugby_league

- From: https://orl-heritagetrust.org.uk/player/harry-glanville/, and the Western Morning News, January 28 1950, p8.

- Harry Edgar, “The Best From the West”, Rugby League Journal, Spring 2005, p22-3. Courtesy Tony Collins.

- Devon won the title in 1901, 1906, 1911 and 1912; Gloucestershire won in 1910 and 1913; and Cornwall, of course, won in 1908. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/County_Championship_(rugby_union)

- Tony Collins, Rugby’s Great Split, p29-66.

- For more on the tribute mining system, see John Rule, Cornish Cases: Essays in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Social History, Clio, 2006, p98-115. For the story of Cornish migration, see Philip Payton, The Cornish Overseas: The Epic Story of the ‘Great Migration’, Cornwall Editions, 2005.

- Information from the 1911 census.

- West Briton, August 17 1911, p6; Cornishman, August 17 1911, p7; Manchester Evening News, December 20 1980, p4 and August 8 1992, p9; Salford City Reporter, 28 April 1994, p87. Injury truncated Launce’s playing career for Salford, though he was still a ticket inspector at the ground until the 1950s: Green Final (Oldham Evening Chronicle Sports Edition), March 8 1958: https://orl-heritagetrust.org.uk/app/uploads/2019/12/greenfinal_1958-03-08.pdf, and https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/sport/rugby-league/the-willows-salford-reds-field-of-dreams-853738

- From: https://www.thereddevils.net/the-club/the-story-so-far/, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Salford_Red_Devils_players

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, August 30 1900, p3.

- West Briton, December 2 1920, p4.

- See: Manchester Evening News, December 1 1920, p3, Cornubian and Redruth Times, October 30 1924, p6, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Harris_(rugby)

- Cornish Telegraph, December 19 1900, p5.

- West Briton, December 2 1920, p4.

- West Briton, June 12 1947, p2.

- Working-class communities in Wales, by contrast, tended to shun anyone who left to play Rugby League, as the 2018 BBC documentary The Rugby Codebreakers makes clear. Players who switched allegiances between Camborne and Redruth RFC have found themselves ostracised by their original clubs and followers. In fact, the treatment of such men is not dissimilar to that of how the RFU dealt with defectors to the NU. See: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/09/09/camborneredruth-the-oldest-continual-rugby-fixture-in-the-world-part-two/

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Gregory_(sportsman)

- Western Daily Press, January 7 1899, p6.

- Lake’s Falmouth Packet, May 10 1907, p6.

- See: West Briton, June 1 1908, p2, and Western Echo, January 16 1909, p3.

- See: James W. Martens, “They Stooped to Conquer: Rugby Union Football, 1895-1914”, in Journal of Sport History 20:1 (1993), p25-41, and Lake’s Falmouth Packet, February 5 1909, p7.

- Coventry Herald, October 1 1909, p5, and Lake’s Falmouth Packet, November 26 1909, p2.

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Jackett, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Davey_(rugby_union). Images from: https://www.trelawnysarmy.org/ta/Pictures/cornwall-team-1908.html. John Jackett’s extraordinary career may be enjoyed here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/06/29/in-search-of-john-jackett-king-of-cornish-sport-part-one/

- Image from: Graham Williams, “How the West Was (Almost) Won!”, in Open Rugby, 51 (1983), p29. Courtesy Tony Collins.

- George Orwell, “The Road to Wigan Pier” in Orwell’s England, ed. Peter Davison, Penguin, 2001, p57-61. The information on Searle is from the 1911 census, and the England and Wales National Probate Calendar 1858-1995, 1928, p239.

- Image from: https://www.mediastorehouse.co.uk/mary-evans-prints-online/new-images-august-2021/comic-postcard-marriage-proposal-commercial-23455214.html

- Unless otherwise stated, the main source of the narrative for this section is: Graham Williams, “How The West Was (Almost) Won!”, Open Rugby 51 & 52, Mar-Apr, 1983, courtesy Tony Collins. I give Searle much more prominence than Williams’ articles. The Western League is also briefly mentioned in: James W. Martens, “They Stooped to Conquer: Rugby Union Football, 1895-1914”, in Journal of Sport History 20:1 (1993), p25-41.

- As noted in the Portsmouth Evening News, September 7 1912, p2.

- Images from: https://www.greensonscreen.co.uk/argylehistory.asp?era=1902-1903_2, and https://www.plymouth.gov.uk/astor-park. See also Western Morning News, July 24 1914, p5.

- Williams, “How the West Was (Almost) Won!”, and the Western Times, May 13 1912, p3.

- Yorkshire Evening Post, July 26 1912, p3; West Briton, August 1 1912, p3. That Searle was on the committee of the Plymouth NU team is noted in the North Devon Journal, December 5 1912, p3.

- See: https://www.rugby-league.com/article/23654/joseph-platt-added-to-the-rfl-roll-of-honour

- Gloucestershire Chronicle, August 17 1912, p9.

- Western Daily Mercury, August 1 1912, p3; West Briton, February 6 1913, p3.

- Western Daily Mercury, August 1 1912, p3 and August 10 1912, p3; quote from the West Briton, August 1 1912, p3.

- Western Echo, August 3 1912, p3. Redruth RFC’s historian Nick Serpell informs me that, on the very same day, Redruth held their AGM. It was stated that they had a received a letter regarding the Western League, but would have nothing to do with the matter.

- From: Lake’s Falmouth Packet, September 6 1912, p2.

- From: West Briton, September 2, p3; September 12, p5; September 26, p8. Kresen Kernow, Minutes and Team Selections, Camborne Rugby Club, 1912-1915. Ref: X1280/1/2.

- Image from: https://www.closedpubs.co.uk/devon/newtonabbot_globe.html

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Kelly_(rugby_union)

- From: Western Daily Mercury, September 23 1912, p3.

- Image from: http://www.exetermemories.co.uk/em/_pubs/rougemont.php

- Western Times, October 19 1912, p3.

- See: Western Times, October 19 1912, p3; Exeter and Plymouth Gazette, October 21 1912, p4, and December 12, p4; Western Times, December 3 1912, p6; West Briton, December 5 1912, p7; North Devon Journal, December 5 1912, p3.

- Cornishman, June 3 1913, p4.

- Graham Williams, “How The West Was (Almost) Won!”, in Open Rugby #52, April 1983, p36. Courtesy Tony Collins.Devon and Exmouth Gazette, January 13 1913, p4.

- Sporting Life, December 19 1912, p1.

- Teignmouth Post, April 3 1913, p4.

- From: Graham Williams, “How The West Was (Almost) Won!”, in Open Rugby #52, April 1983, p36. Courtesy Tony Collins.

- Quote from the Western Times, June 2 1913, 3. See also: Western Guardian, February 13 1913, p7 and April 17, p3; Wigan Observer, March 4 1913, p3. For a sample of the few matches that were played, see: Western Times, January 20, 27 and February 3 and 10, all page 3; Teignmouth Post, April 3 1913, p4.

- West Briton, June 12 1947, p2. The report noted that the teams wowed the crowd with their deft handling skills, but felt a proper Cornish rugby fan yearned for a good hard scrummage.

- Graham Williams makes the assertion in “How The West Was (Almost) Won!”, in Open Rugby #52, April 1983, p36. Courtesy Tony Collins. The CRFU’s stance is noted in Lake’s Falmouth Packet, December 27 1912, p6. Rochdale Hornets played both men in an “A” match in October 1912 whilst the NU was still investigating the circumstances of their Union suspensions. Adopting a holier-than-thou attitude, the NU fined the Hornets £2 (£189 today) for playing men under suspension by another body, and then forgot all about it. From: Rochdale Times, October 9 1912, p5.

- Hull Daily Mail, September 3 1912, p8.

- See: Rochdale Times, December 25 1912, p5. Tom’s ‘A’ appearances are noted, for example, in the Wigan Observer, November 5 1912, p3; and the Leigh Chronicle, November 22 1912, p7.

- In early 1914, whilst Sam was having a star game for the Chiefs, Tom was still plugging away in the second-string outfit. Rochdale Times, January 4 1914, p6.

- Rochdale Observer, February 11 1914, p5 & 6.

- Rochdale Observer, February 18 1914, p6; Yorkshire Post, February 16 1914, p4.

- 1939 Register, 1921 Census.

- England and Wales, Civil Registration Death Index 1916-2007, Vol. 10d, p81.

- As observed in the Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 16 1911, p10.

- Rochdale Times, October 20 1915, p4.

- Sam’s tally of matches for the season is noted in the Rochdale Times, April 15 1914, p7.

- See Tony Collins’ essay on Northern Union rugby during World War One here: https://tony-collins.squarespace.com/rugbyreloaded/2014/8/5/rugby-league-in-world-war-one

- From the Rochdale Times, March 1 1922, p6, and March 29, p5 & 6.

- The Hornets beat Leeds in the second round, and Widnes in the semis. See the Rochdale Times, March 15, p6, April 12, p6, and May 3, p6.

- Sam’s total appearances are noted in the Rochdale Times, May 3 1922, p6.

- The Means Test was introduced in 1931 as a means to cut expenditure on dole money. Households were assessed on their ability to support an unemployed member of the family. Many found their benefits reduced on account of their being a child in part-time employment, or a grandparent living in the house rent-free, and caused much social unrest. See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/z86vxfr/revision/2

- The Labour candidate observed that, while there may not be a better sportsman that Carter, there were certainly better politicians. See: Rochdale Observer, October 29 1932, p6, and November 2, p5. The strike of the cotton operatives is mentioned on page four of the latter edition of the Observer.

- Sam’s 1911 census entry makes mention of this remarkable feat in a note, and is confirmed by Adrian Wallace, a relative of Sam.

- England & Wales, National Probate Calendar, 1858-1995, 1968, p73, and 1980, p441.

6 thoughts on “The Great Cornish Rugby Split?”