(If you missed Part One, click HERE…)

Reading time: 25 minutes

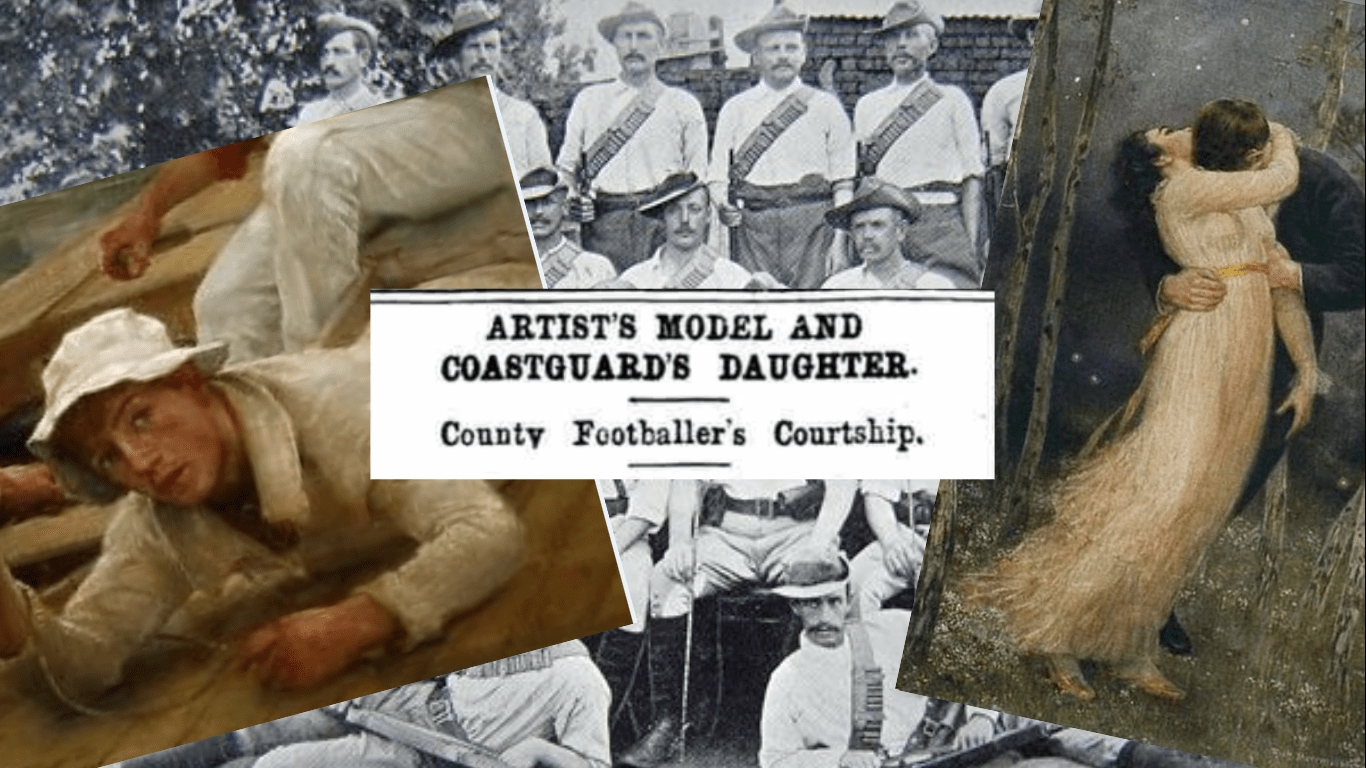

…SHE YIELDED TO HIM…SUCH A BASE DECEIVER…

~ John Jackett becomes the boy that daughters are warned about1

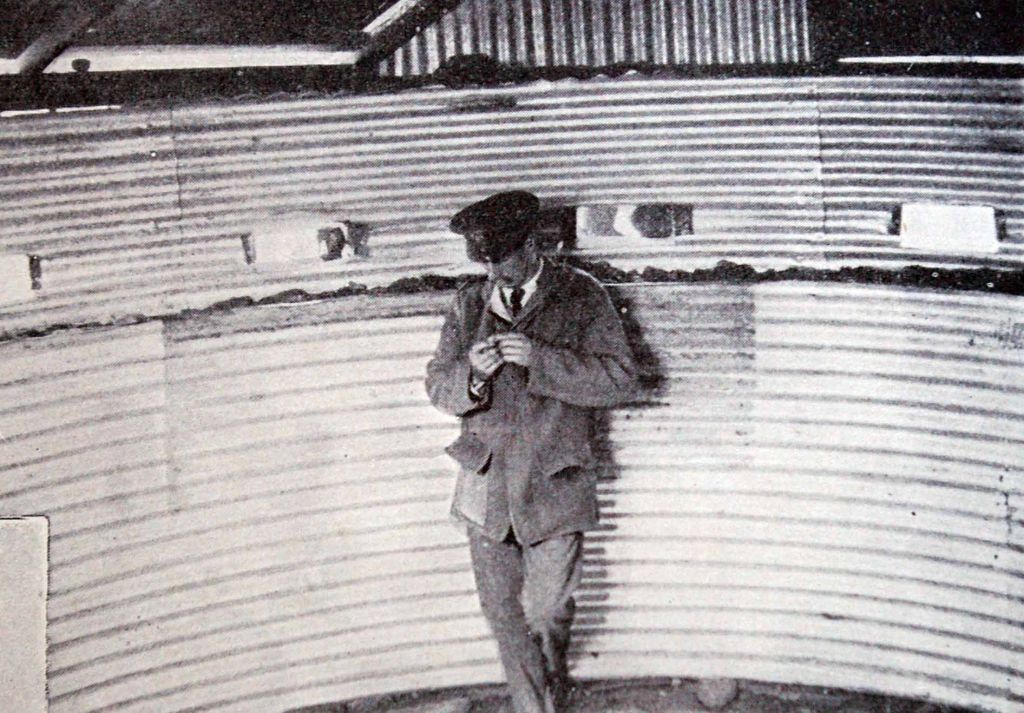

Life in 1898 and for part of 1899 must have been pretty good for the young John Jackett. In Henry Scott Tuke he had an employer who was more a friend than a boss. Posing as a model in several of Tuke’s paintings earned Jackett extra money, and started gaining him recognition.

Furthermore, the avuncular Tuke appears to have allowed Jackett ample time to compete as a track cyclist and play rugby. As a full-back, his rise through the ranks was rapid, and he had made his debut for Cornwall in November 18982. Doubtless Tuke was a spectator.

In cycling, he was already Cornish Champion over the One Mile, and had won numerous other prizes. At Falmouth in 1899 he took possession of a 60 guinea silver cup (worth around £6,500 today) for winning a prestigious five mile race – but had to return it to the officials at the end of the season3. He had an all-or-nothing racing style that made him a crowd favourite.

He may not have wanted a career in his father’s boatbuilding business, but he was making a decent, if somewhat chancy fist as a sportsman, an occupation at which he worked hard and dedicated countless hours to. He swore off alcohol – though enjoyed the odd cigarette – and was one of the fittest men around. He’d be one of the fittest men around now. He was also one of the best-looking.

Local girls, impressed with Jackett’s achievements – and his looks – would visit his father’s house, ostensibly to admire the burgeoning silverware.

Perhaps inevitably, one girl caught John Jackett’s eye.

Very soon, he was in the Press for all the wrong reasons.

A Very Victorian Melodrama

Breach of promise actions, though not officially abolished until 1970, enjoyed their greatest frequency in law courts during the 1800s. By the time Over v. Jackett appeared at Bodmin Assizes in early 1900, a breach of promise case was, by the standards of the day, a media extravaganza5.

There are several reasons for this Victorian proliferation of breach of promise cases. The majority of actions were initiated by upper working- and lower middle-class women, a social group not normally afforded a voice or platform at that time. (Caroline Over, Jackett’s lover-turned-accuser, vanishes from view at the conclusion of the case7.) Indeed, male fears of feminine power in using or exploiting the breach of promise act

…became increasingly shrill as the century wore on.

Ginger S. Frost, Broken Promises, p7

There’s no denying that breach of promise cases were heavily biased in favour of the female plaintiff and therefore, in the view of many males, threatened gender roles. However, it was their ultimate reaffirmation of Victorian society’s hierarchy that sustained their longevity.

Courtship and marriage implied middle-class respectability; to break off that courtship and engagement (to break your promise), was an act of subversion punishable by law. In other words, it was illegal to shun

…the value of companionate marriage and romantic love…

Ginger S. Frost, Broken Promises, p8

Breach of promise cases reinforced Victorian gender roles as well. Men had to take responsibility for their actions, as well as keep their promises. A man’s word is his bond. Women were to be chaste (most of the time), respectable and industrious. They must also, in the prevailing culture of the time, want a husband. If that opportunity was taken away, compensation through the court could be sought.

The 1753 Marriage Act secularised breach of promise cases, allowing for greater publicity. With the newspaper boom of the 1800s, crime coverage grew exponentially, and contributed to a reinforcement of the social order8. Crime also sold newsprint, and a breach of promise case had journalists sharpening their pencils with glee.

The Royal Cornwall Gazette ran Over v. Jackett with the following melodramatic headline:

The Cornishman went for the tabloidesque

The Cornish Echo promised its readers a “full and special report” of the events in Falmouth that had superseded

The [Boer] War as a topic of conversation…

February 2 1900, p7

A breach of promise case was a Victorian soap opera. Everyone knew the script, but everyone could wallow in the entertainment (and think themselves lucky it wasn’t them in the dock, having their linen examined).

Prosecuting lawyers would portray the woman as an innocent, pathetic maiden, and the man as a heartless lothario with a capacious wallet. Counsels for the defence would tell juries – and packed public galleries – that the man was a poor, hapless bachelor, and the woman a husband-hunter on the make.

Due to the private nature of courtship, judges would accept circumstantial evidence and hearsay. Analysis of breathless declarations of love, the reports of exchanged gifts and recitations of (very) personal love-letters ensured that

…the trials were very popular as entertainment.

Ginger S. Frost, Promises Broken, p25

Juries were selected from the local populace; packed public galleries would have been familiar with both plaintiff and defendant. Shameless titillation was on the menu.

There would be tears, jeers, laughter, brow-beating barristers and moralising judges. Everybody had their allotted role.

All of which means that, discovering the truth behind the media obfuscation of Caroline Over and John Jackett’s relationship is rather difficult.

The truth, the whole truth…

Caroline Amelia Over was born in 1876, in Mevagissey. In the 1890s the Overs moved to Portscatho, where her father was a coastguard10. Caroline, described as a

…young woman of respectable and somewhat prepossessing appearance…

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

…met Jackett in around early 1897. (Where and exactly when is unknown; it’s mere speculation on my part to assume she was one of the girls who visited the Jackett household to admire the crack cyclist’s trophies.) The two became a couple, visited each others’ homes, and exchanged letters.

In January 1899, they slept together, and Caroline became pregnant. The baby boy, John Jackett Over, sadly died aged three months in December11. Thomas Jackett had advanced Caroline £50 for his grandson’s upkeep.

As regards their relationship, the above is all that can be concluded with anything like 100% reliability. Anything else you may wish to infer depends on whose version of events you trust.

The following letter from Jackett to Caroline was read aloud in court. Jackett (we are told) joined in the gales of laughter from the gallery, but he must have been cringing inside:

…I could live with you all my life, but I fear it could not be done at present…I get no kisses from anyone but you, I don’t know why, but I suppose it is my face that stops them…

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

Such missives, including one that allegedly illustrated Jackett’s intentions for them to live in Mevagissey, were taken as gospel by the prosecution that the couple were engaged by 1898.

(Over’s lawyer couldn’t resist the opportunity to upbraid Jackett’s supposedly false modesty as regards his looks, much to the gallery’s hilarity. I wonder if he laughed along with that one.)

Jackett stated that his letters can be interpreted

…as you like…

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

And, Jackett went on,

Never in my life…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, February 1 1900, p8

…had he contemplated marriage. Miss Over must have gotten the wrong end of the stick. As for living in Mevagissey, your honour? Well, that was another misunderstanding. We were planning to visit a relative there.

As Mandy Rice-Davies once said, Well, he would say that, wouldn’t he?

Of course, these letters-as-proof-of-engagement were written by Jackett when he was twenty – before his legal coming of age. Any promise of marriage made by an immature Jackett could not be held against him in a court of law.

However, a precedent had existed since the 1880s that stating ‘I will marry you’ again, after coming of age, constituted a new – and legally binding – promise. This new promise was not a mere ratification of the earlier promise13.

Caroline Over and her family, if they wanted damages

…for the pain, grief, and disappointment which plaintiff had suffered…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, February 1 1900, p8

…needed a 21 year-old Jackett to have proposed marriage.

In July 1899 Caroline wrote to Jackett, inviting him to meet her at Portscatho Regatta. Jackett declined. Undeterred, Caroline appeared at Thomas Jackett’s house with her sister Susan, who seems to have been no friend of John Jackett.

His and Caroline’s relationship had cooled over the past months. Apparently this was the first time Jackett had seen her since she fell pregnant.

Susan Over would later state that she accosted Jackett on the street, as he was returning from a bike ride:

Well, Jackett, the best thing you can do is marry her…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, February 1 1900, p8

We can imagine her standing indignantly, arms folded, onlookers with mouth agape. Her sister, her head bowed in shame over the indisputable evidence of her relations with Jackett. And the man himself, caught off-guard, looking desperately for a way out.

It’s an irresistible image. According to Caroline, Jackett said,

My God, what shall I do. I can’t marry you now, Carrie, but I will do so. Don’t worry…

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

By the time of the Portscatho Regatta, Jackett was twenty-one. The Overs had their proof of a mature, legally-binding, promise of marriage.

Jackett denied making the above statement, saying that Susan Over’s attempt at a shotgun wedding in fact elicited the following response from him:

That is the last thing I should do.

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

Indeed, Jackett’s plea rested on the assertion that he had only made a promise of marriage before coming of age. Caroline Over’s testimony pretty much sealed a guilty verdict.

But the hearing went on. Caroline gave the court the impression Jackett was earning well, up to £1 as an artist’s model, and had secured £150 worth of prizes as a cyclist (her lawyer claimed he was a professional racer).

She also stated Jackett made money as a professional rugby player, but more on that to come.

For his part, Jackett either denied or played down these claims. He was an amateur rugby player. He was an amateur cyclist – this was certainly true. He was unsure how much he’d won in prizes. He only got 8s a week with Tuke, something that was scarcely believed, with Tuke being

…an artist of great eminence.

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

Jackett also claimed that he only worked for Tuke seven months in every year; the other five months he was free to do little else but play rugby and cycle.

The Overs wanted a wealthy Jackett, a high-earning pro sportsman and model, who could more readily afford the damages that was surely coming his way. Jackett tried to project an image of himself as a modest live-in servant, who played sport for fun. Doubtless, he’d been briefed on this.

Where does the truth lie? Similarly, Caroline’s father claimed Jackett was a regular visitor to their house. Jackett said he had only visited once or twice. For this last refutation, the judge threatened him with perjury, which may give you an indication as to where the court’s sympathies lay.

Jackett’s lawyer’s final address is surely one of the most callous speeches in legal history. Caroline

…was a girl who was older than the defendant, and who knew what she was doing…provision would have been made for her baby, but happily for the girl that was dead…it was better for her not to marry a lad who was earning eight or nine shillings a week…

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

Over’s counsel cut this line of argument to ribbons. Caroline had

…lost what was of more value than money, and unfortunately money was the only thing that could give her any consolation for her loss, and he hoped the damages would be substantial…

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

Caroline had lost her fiance, her child, her prospects and her honour. Jackett had ruined her.

Heartstrings successfully tugged, there was only going to be one verdict. Caroline was awarded £150 damages (that’s £15K today), with costs, to be paid by Jackett.

Scoundrel

Regardless of whether Jackett was deliberately modest about his income in court, the verdict cleaned him out. Besides, Tuke had already advanced him £50 (£5K today) of his wages to cover the cost of the trial17.

Allied to this, his reputation must have been shredded. Just recently, he had been the darling of Cornish sport, the coming man. On a bike, it had been written of him that his

…staying powers for a young rider are somewhat remarkable…

Western Morning News, June 20 1898, p6

As regards rugby, the pundit ‘One of the Crowd’ rejoiced

…to see that he [Jackett] has been selected to play for his county. I look forward to his acquitting himself with credit…

Cornish Telegraph, October 27 1898, p4

Not any longer. Now John Jackett was a

…base deceiver…a scoundrel…

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

He had led a young girl astray, failed to heed any warnings from his father, and now look at the result18.

The news travelled far and wide. London’s Cycling magazine picked up the story, with some wag noting that

Miss Over gained her suit, but lost her Jackett.

February 10, 1900, p42. With thanks to Victoria Sutcliffe and Danny Trick of Falmouth RFC for showing me this

People would have looked at him differently. Maybe they avoided him. One shudders to think of the smart-mouth remarks he may have endured in various changing-rooms. The strain must have been immense.

It must be said, though, that John Jackett didn’t exactly cover himself in glory with this particular episode. Put bluntly, it looks like he got a girl pregnant, then abandoned her.

There is also a suggestion that Caroline Over may have been one of many, part of a

…Galaxy of young lady admirers…

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

How many girls, like Caroline, had been taught by Jackett to ride a bicycle19? As his mother, Emmeline, told Caroline,

Don’t you think he is completely laughing at you?

Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7

Jackett’s wife, Sallie (they married in 1909), was more than aware of her husband’s adventurous youth:

Of course John has had 1001 girl friends…[he] had plenty of noes and plenty of yesses…

Qtd. in Henry Scott Tuke 1858-1929: Under Canvas, by David Wainwright and Catherine Dinn, Sarema Press, 1989, p60

To which observation Tuke himself is supposed to have ruefully replied that

…that was the real Johnny I knew…

Qtd. in Henry Scott Tuke 1858-1929: Under Canvas, by David Wainwright and Catherine Dinn, Sarema Press, 1989, p60

The real Johnny Jackett was saddled with debts he couldn’t pay.

So he didn’t pay them.

Cigarette money

Approximately a year later, Jackett was hauled into Falmouth County Court for non-payment of damages22.

Caroline Over was unwell and could not attend, but her mother testified against Jackett. The image she paints is that of a mercenary professional sportsman and braggart:

…when he went footballing at St Austell he had £1 5s a week, but he only looked on that as cigarette money. He looked for more at Plymouth, and she did not know how much he had at Penzance.

Cornish Echo, February 8 1901, p5

Jackett, Mrs Over claimed, was earning 7s a day for Tuke, had cash in the bank, and could always make himself some extra tin at his father’s boatyard.

Jackett denied all this. He’d never said £1 5s was mere spare change for fags. He was strictly an amateur footballer. He had never played for St Austell (which was true). He had always played for Falmouth (which was untrue; he was currently with Devonport Albion and had also played for Penzance).

Furthermore, he didn’t work with his father, and currently earned only three shillings a week with Tuke – and that for only seven months in the year.

The Overs’ lawyer was flabbergasted – and he probably wasn’t alone:

Mr Dobell: Twenty-two years of age, and three shillings a week (Laughter). These five months how do you manage to keep yourself in cigarette money?

Jackett: Get it from my father…

Cornish Echo, February 8 1901, p5

Mr Dobell further asserted that Tuke allowed Jackett time to cycle and play rugby, and surely paid him bonuses as a model:

I think I have seen your face and figure represented in a picture?

Jackett: No, sir.

Cornish Echo, February 8 1901, p5

Doubtless, Mrs Over was exaggerating Jackett’s income. If we are to assume that to be the case, then we must also assume that Jackett was reverting to the role of near-pauper he played in the previous trial.

Unluckily for him, Jackett was over-egging it. His claims to live on 3s/week (albeit with bed and board thrown in) are utterly unbelievable.

To put this into some perspective, in 1889 a miner at Dolcoath could expect to earn £4 a month23. If, as Jackett claimed, he earned nothing all year except the 3s/week for the seven months Tuke employed him, then his annual income was a mere £4 2s.

If this was an enquiry into allegations that Jackett earned money as a sportsman, then surely something like the following question would have been asked:

What is a top rugby player and champion cyclist living off, given he’s unemployed five months of the year, and earns a pittance the rest of the time?

Who’s paying for his cigarettes?

Fortunately for Jackett, the hearing was only to assess his ability to pay the damages Caroline Over was due. He needed to prove his income was, indeed, as pitiful as he claimed. The more pitiful his income, the more chance he had of the impact of the £150 demanded of him being in some way alleviated.

So he played his ace.

Henry Scott Tuke. An ‘artist of great eminence’. A gentleman of some standing.

And Tuke, not for the last time, came to his aid24. Jackett indeed only earned 3s/week when he was employed by him; after all Tuke had advanced him three years’ wages to cover the cost of the first trial.

Thomas Jackett provided further weight. Swallowing his parental pride, he stated that it was true his son didn’t work for him. He hadn’t the aptitude.

Dobell might have been prepared to browbeat and mock John Jackett, but you don’t look down your nose at men of the status of Henry Scott Tuke and Thomas Jackett. The prosecution can’t have liked it, but Jackett opening his wallet and casually thumbing out £150 in cash wasn’t going to happen.

John Jackett was ordered to pay 5s/month to the Overs, until the £150 – and costs – were cleared.

*

Although a frequent sight in courts across the land during the 1800s, many breach of promise cases didn’t result in the bumper payouts many female plaintiffs hoped for. As one historian notes,

…probably a large number of defendants never paid damages…

Ginger S. Frost, Promises Broken, p35

There were many ways to avoid paying an ex-lover. One of the more common methods was for the man to escape abroad and lie low until, hopefully, the whole sorry mess had blown over25.

John Jackett went to South Africa. He signed up for three years.

The Run Home

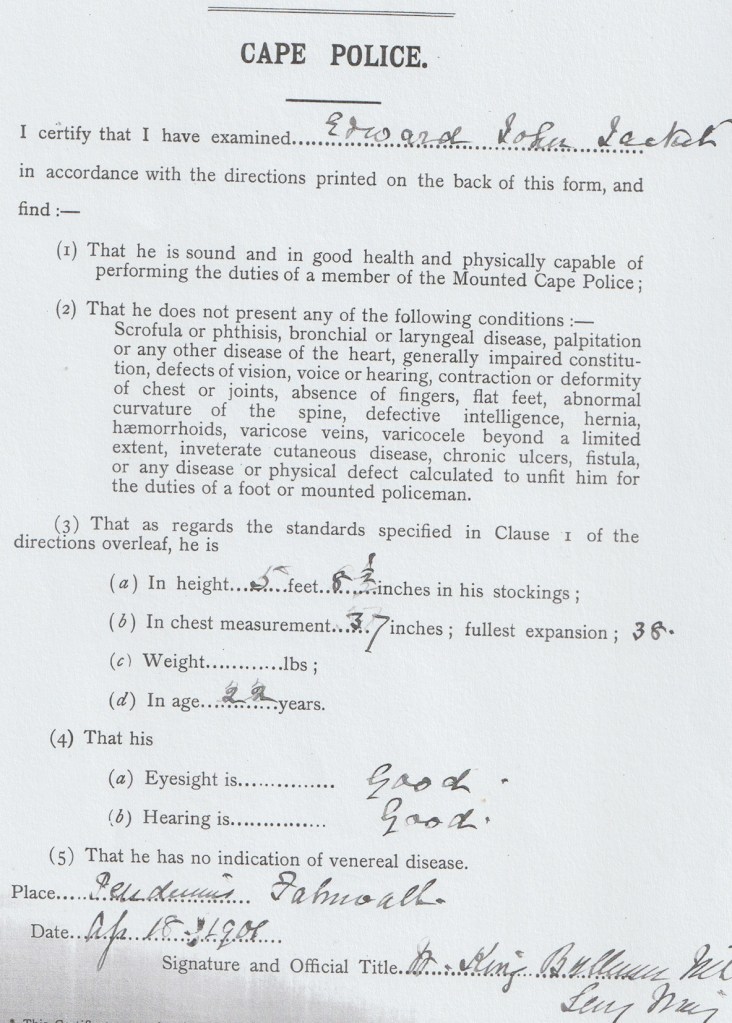

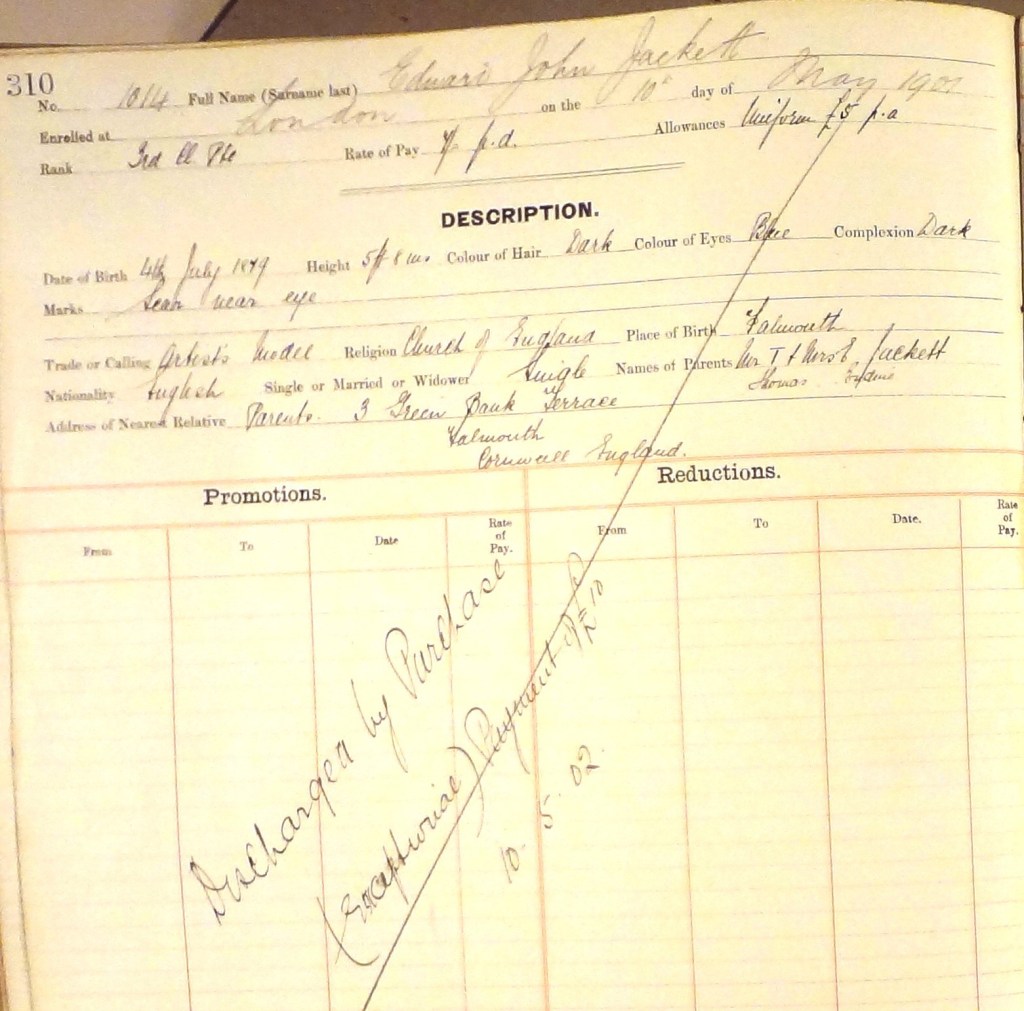

The Attestation Papers of over 5,000 men who joined the Cape Mounted Police before, during and after the Boer War (1899-1902) are held in the Western Cape Archives, Cape Town.

It is not known how many sets of Papers have been lost. Those that have survived are in a poor state, often with pages missing. At some point, they were boxed up in a seemingly random order26.

Mercifully, a volunteer, Adrian Ellard, has indexed and digitised what Papers remain. To him I am incredibly grateful.

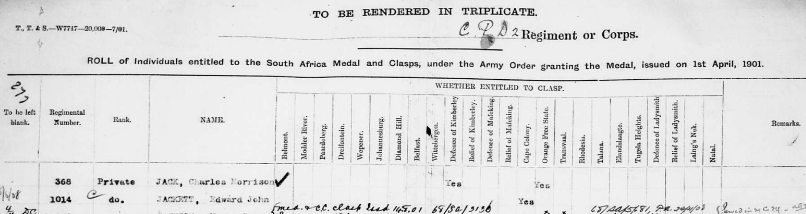

Luckily for us most of 1014 Trooper John Jackett’s Attestation Papers still exist.

One can learn a lot from such records.

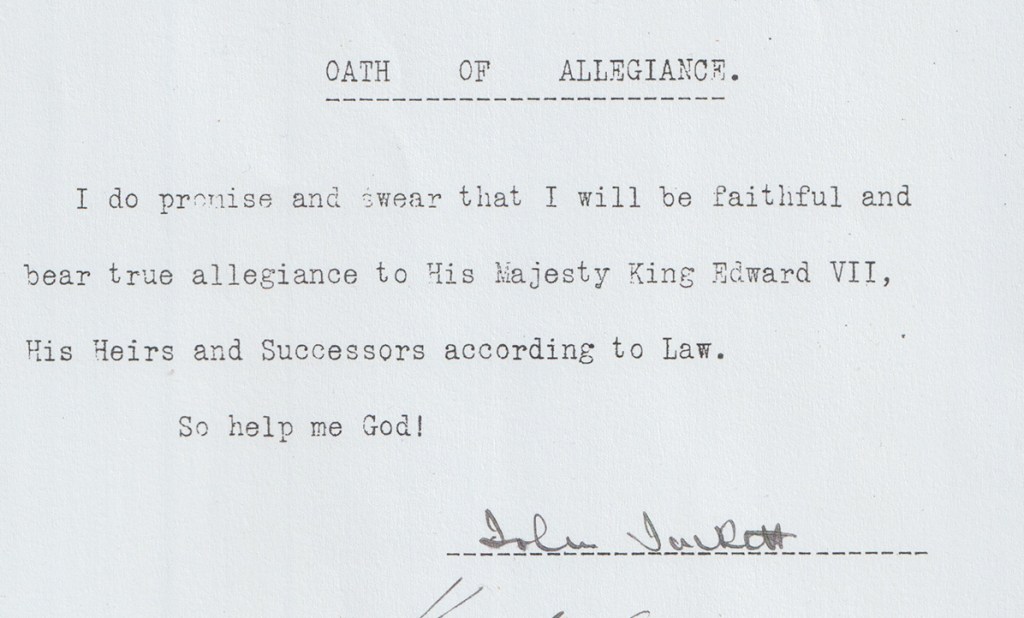

We know he took an oath of allegiance to Edward VII (or rather, one of his representatives) on June 1, 1901 at Kimberley (the training camp for new recruits).

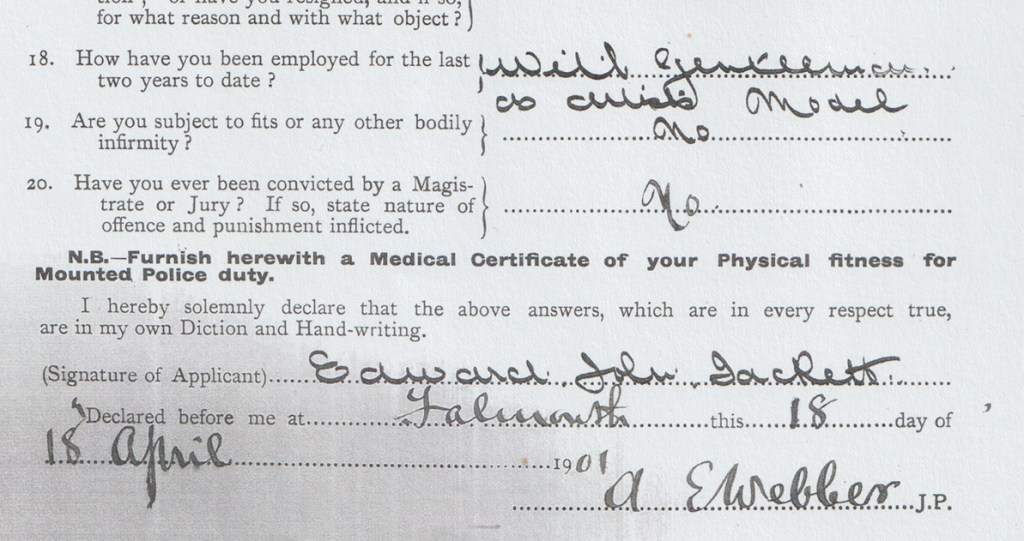

We know he enrolled and underwent a medical examination (now, cough…) in London on May 10. Because of this we know he thought he was born in 1879, not 1878. He was 5ft 8″, with blue eyes, dark hair, and a scar near one of his eyes.

We also have his original application form, submitted in Falmouth on April 18. We know that Tuke supplied a letter of reference, that he was single, could shoot, weighed 11 stone and he had rather neat, stylish handwriting.

We also know he lied on this form, declaring that he had no convictions.

He also underwent a medical in Falmouth. His chest was measured at 37″ – and he was free of venereal disease.

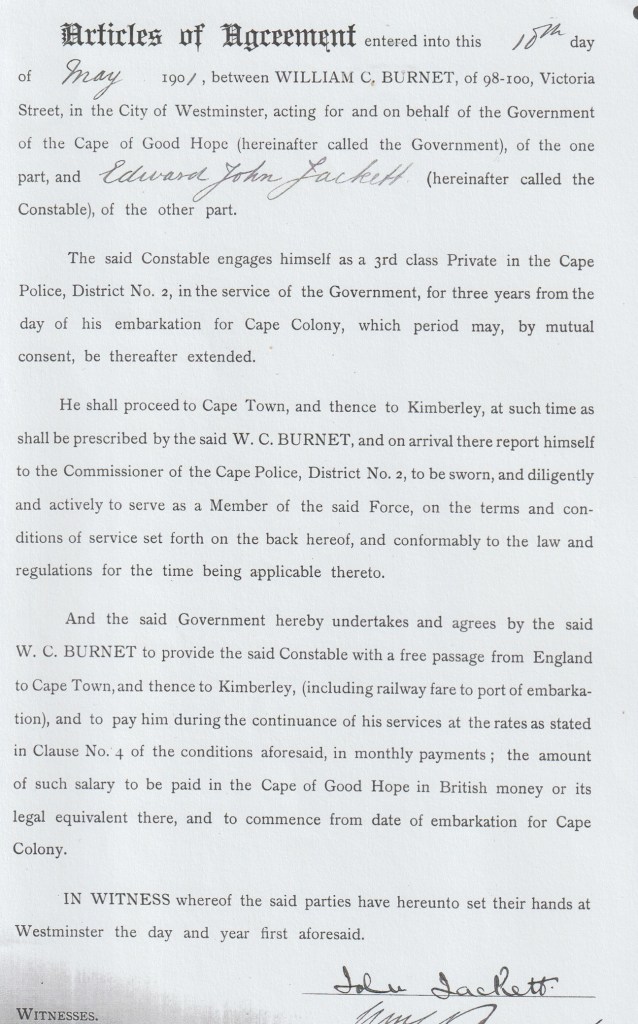

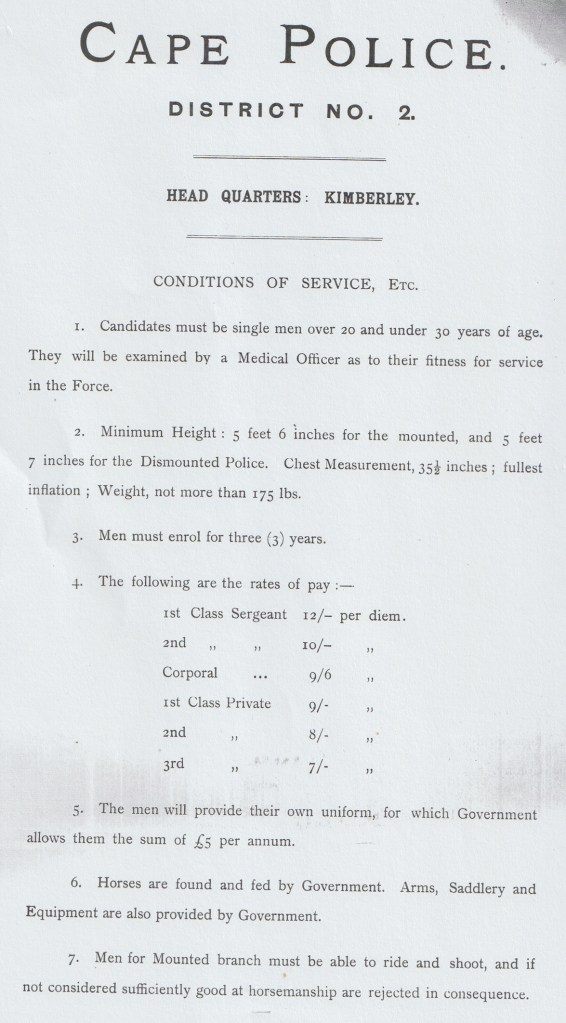

On May 10, he signed the Articles of Agreement in Westminster. John Jackett was now a Private, 3rd class, of the Cape Police, 2 District. He was given free passage to Cape Town and thence by rail to Kimberley. The Articles stipulated three years service.

He would be provided with his own horse, money for uniform, and would earn 7s/day.

All of which is very interesting. But none of these precious documents give us the answers to two very important questions:

What did he actually do in South Africa?

Why did he quit the Police after only a year?

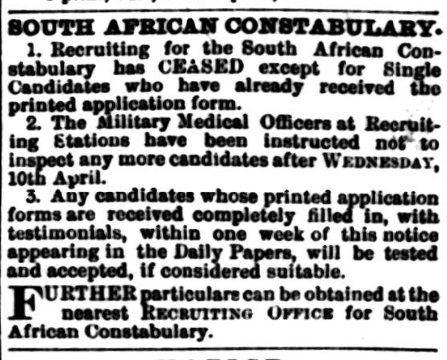

We can infer that, as his application was submitted on April 18 – the deadline day specified in the Royal Cornwall Gazette (above) – Jackett’s decision to take the new King’s shilling was a last-moment one, that may have caused some hand-wringing.

His signing-up almost certainly cannot be borne from a sense of duty or patriotism. After all, the Boer War had been fought since 1899, and was about to enter its most unpopular and bitter phase with the British public. It divided Cornish loyalties between the Boers who had welcomed them to the diamond mines, and Britain’s imperial interests and and prestige27. One can only conclude he left because of the cloud he found himself under regarding Caroline Over.

Jackett would have had no problem proving his fitness, nor his aptitude on a horse. In May 1900, he had faced Falmouth’s populace on horseback, albeit in disguise. The dual-celebrations of Queen Victoria’s birthday and the relief of Mafeking saw Jackett impersonate the siege’s hero, Lord Roberts, for the crowd’s amusement28.

We also know that, if Tuke supplied a suitable reference for Jackett’s application, he also saw his friend off. He treated Jackett and three rugby-playing comrades who also joined up (Christophers, Toy and Coleman) to an evening out in London and a slap-up meal at Gatti’s, Tuke’s joint of choice whenever he was up in Town29.

Jackett’s own recollections of his tour of duty are contained in two newspaper interviews. The first was for Lake’s Falmouth Packet, given shortly after his return to Falmouth on June 7, 190231.

The second was for the Dewsbury Reporter of March 3, 192832. His nephew, Ivor Jackett was due to play for Cornwall against Yorkshire in Bradford for that season’s County Chamionship. As Uncle John played no small part in the last time Cornwall lifted the trophy in 1908, a Dewsbury stringer had sought him out.

Both interviews must be approached with caution. If Jackett lied in his application to the Police, what did he falsify or exaggerate for the Press?

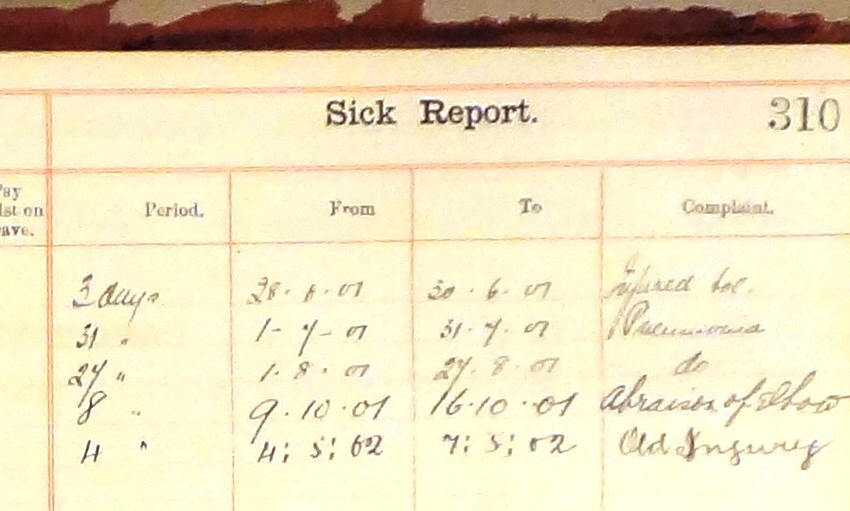

That said, one thing can be confirmed in his interview for Lake’s. Shortly after arriving in Kimberley, Jackett contracted pneumonia. Though he blithely put his recovery down to an iron-clad, teetotal constitution, it was serious enough to see him hospitalised for two months. Four other recruits who fell ill died.

Tuke heard of this back in Cornwall, and was seriously emotionally affected. Plagued by dreams (or nightmares) of his stricken friend, he was moved to paint The Run Home:

Tuke painted himself as the figure at the helm, guiding the young Jackett (lying prone and staring out of the canvas at the viewer) to safety. It has been argued that

…Tuke launches a rescue mission in his painting. He recovers Jackett and brings him home to Falmouth. Tuke did not see the point of losing in South Africa another man, a beautiful inspiration for his art and desire.

Jeremy Kim Jongwoo, “Naturalism, Labour and Homoerotic Desire: Henry Scott Tuke”, in: British Queer History: New Approaches and Perspectives, ed. B. Lewis, Manchester University Press, 2013, p4635

Overall, though, Jackett described his time as a Policeman as “dreary”, and he certainly emphasises this.

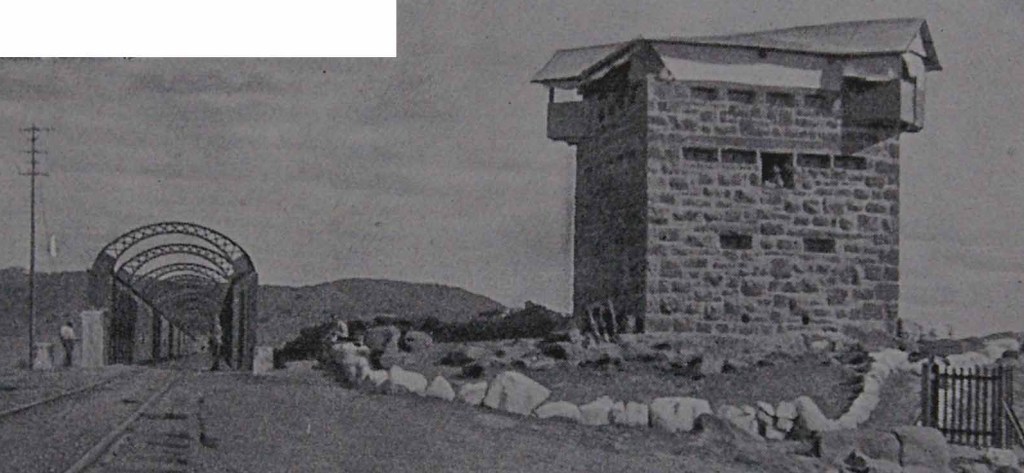

Holed up in a cramped blockhouse near Kimberley all day, going on the odd patrol, and doubtless eating sweaty bully-beef out of a tin, you’d wonder there was a war on at all.

Sport, Jackett informs the wide-eyed reporter, kept him from dying of boredom. He played rugby for the local Police XV, and turned out for the nearby De Beers Mine team. (The De Beers Group had been founded in 1888 by Cecil Rhodes; both his actions and his mine contributed to the war’s outbreak37.)

He also won cycling races, and was even prominent in various sporting events during his voyage home. There is a report of him playing a game of Association football in Kimberley, and a belief has also developed that he turned out for Transvaal against the 1903 British Lions, but this can’t have happened. He was already back in Cornwall38.

Jackett is keen to present a certain image of himself to the public, a public that was by now largely opposed to a war fought by scorched earth policies and concentration camps39. Although debate raged as to the reality of the conditions in the camps40, there’s little doubt that measles and other diseases made

…camp life in winter fatal to a large number of children and weakly persons.

Daily News (London), November 7 1901, p10

As one historian has observed, during the Boer War

Almost 50,000 innocent people lost their lives in concentration camps due to overcrowding, malnutrition and rampant levels of diseases.

Sharron P. Schwartz, Cornish Mineworkers in South Africa42

Lest we forget, there was one such camp at Kimberley. Located on De Beers land, it housed 5,000 inmates, not enough tents, lots of whooping cough and rudimentary medical knowledge43.

By not mentioning if he ever saw duty as a guard there (and we may never know the truth), Jackett in his interview is putting distance between himself and the horrors of the Boer War. Such unpleasant goings-on were not part of his experiences.

No, he’d been abroad, got a tan, gained a few pounds, and played sport, all for a decent wage.

That was all he would tell Lake’s – and it may have been all Lake’s wanted to hear.

By the time we reach the Dewsbury Reporter interview of 1928, Jackett has honed his story. He had “ran away from home” with friends, after being

…enamoured of a wandering life…

Once reaching South Africa, he

…indulged in sport to his heart’s content…

He won a prized trophy in a championship cycle race organised by De Beers. A bigwig of the mining corporation, a fellow Cornishman, had also offered him a “good position” on the firm. This last is almost certainly a fiction. Jackett was never a mining engineer, and much less a miner.

He never told that tale in Cornwall because nobody would have believed him. He also told the Reporter that his mother eventually

…bought him out of the mounted police…

Which may very well be true. Jackett’s discharge papers show that someone bought him out for £10, or just over £1,000 today:

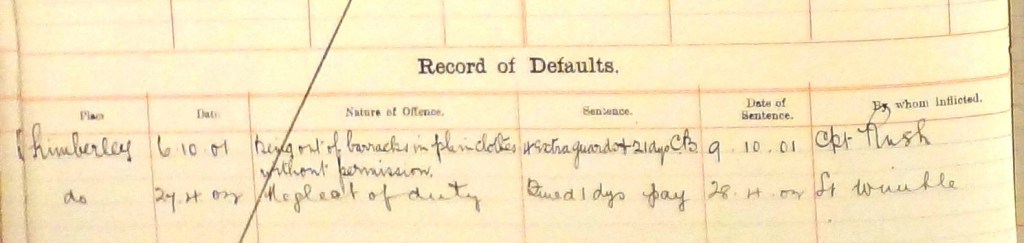

We can also conclude that, whatever Jackett’s duties may have been, he wasn’t especially diligent in executing them. These papers tell a very different story of Jackett’s war than the one he himself liked to tell.

He was docked a day’s pay for neglect of duty, and given three weeks’ additional guard duty for being caught out of barracks, out of uniform, and without permission. Who knows what he was up to, but you certainly couldn’t ‘play sport to your heart’s content’ if you’ve extra duties to carry out.

Besides the pneumonia, he also suffered an infected toe, a bashed-up elbow, and another old injury apparently flared up too.

The sparse official record of Jackett’s time in the Cape Mounted Police suggests a very different experience than the one he described himself.

Certainly one thing neither Lake’s or the Reporter mention is the scandal involving Caroline Over. He may have agreed to talk to Lake’s on condition it wasn’t mentioned, and the Reporter obviously had no knowledge of the business.

In fact, the £150 damages he owed to Caroline are never mentioned in public again. You like to believe that, on his good Policeman’s pay, he could afford to make things right in that regard. But that’s a question that cannot be answered.

Until South African newspaper archives become more easily available (or someone commissions me to spend two weeks in Cape Town), we will never definitively know what Jackett’s duties in the Boer War were. We can say, however, that the rosy picture he painted for the Press doesn’t bear much close scrutiny.

But now, the carefree, sport-loving John Jackett was back. Back, and ready to devote his energies to what he was probably best at.

Playing rugby.

Read all about his stellar – and controversial – Rugby Union career in In Search of John Jackett, Part Three by clicking HERE…

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Excerpts are from the Royal Cornwall Gazette, February 1 1900, p8, and the Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, November 3 1898, p5.

- Western Morning News, August 4 1903, p7. This seems to have been common practice for such expensive trophies – and important race events. Previous winners had travelled from Bristol and Oxford University to compete for the five mile cup in Falmouth, and to own it in perpetuity you had to win the race over three seasons.

- Image from: https://thepoly.org/history-archive/item/23/edward-john-jackett

- Informing this section is Ginger S. Frost’s Promises Broken: Courtship, Class, and Gender in Victorian England, Virginia University Press, 1995.

- Image from: https://thisivyhouse.tumblr.com/post/160526080358/connoisseur-art-richard-borrmeister-lovers

- In the 1901 census, she appears as a parlour-maid at a residence in St Marychurch, near Torquay. Possibly, aged 41, she married a David W. Evans at Bristol in 1917. England and Wales, Civil Registration Marriage Index 1916-2005, Vol. 6a, p421.

- See: Bethany Usher, Journalism and Crime, Routledge, 2024, p98-133.

- Image from: http://www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk/data/projects/FS/Series/Breach%20of%20Promise%20Series.htm

- England and Wales, Civil Registration Birth Index 1837-1915, Vol. 5c, p139. The Overs’ move to Portscatho, and the rest of the narrative in this section, is taken from the Royal Cornwall Gazette, February 1 1900, p8, and the Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7.

- England and Wales, Civil Registration Death Index 1837-1915, Vol. 5c, p85.

- Image from: http://www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk/data/projects/FS/Series/Breach%20of%20Promise%20Series.htm

- Frost, Promises Broken, p22.

- Image from: http://www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk/data/projects/FS/Series/Breach%20of%20Promise%20Series.htm

- Image from: https://racingnelliebly.com/fashion-forward/victorian-couples-embraced-romance/

- Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melodrama

- Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, February 1 1900, p8.

- Cornish Echo, February 2 1900, p7.

- Image from: https://www.economist.com/culture/2022/05/26/the-bicycle-is-humanitys-most-underrated-invention

- Image from: https://rugby-pioneers.blogs.com/rugby/2012/02/my-entry.html

- The narrative for this section is taken from: Cornish Echo, February 8 1901, p5 and March 8 1901, p4; Royal Cornwall Gazette, February 14 1901, p3.

- Information from: “Rational Choice and a Lifetime in Metal Mining: Employment Decisions by Nineteenth-Century Cornish Miners”, by Roger Burt and Sandra Kippen, International Review of Social History, Vol. 46.1 (2001), p45-75.

- As we saw in Part One, Tuke saved Jackett from drowning in 1905. See: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/06/29/in-search-of-john-jackett-king-of-cornish-sport-part-one/

- Frost, Promises Broken, p35-7.

- Information from: https://www.angloboerwar.com/unit-information/south-african-units/310-cape-mounted-police?start=1

- For more on the Cornish in South Africa, see Sharron Schwartz’s essay here: https://www.cousinjacksworld.com/cornish-mine-workers-in-south-africa/

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 31 1900, p7. For more on Lord Roberts, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Mafeking, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Roberts,_1st_Earl_Roberts

- From: “Naturalism, Labour and Homoerotic Desire: Henry Scott Tuke”, by Jeremy Kim Jongwoo, in: British Queer History: New Approaches and Perspectives, ed. B. Lewis, Manchester University Press, 2013, p44.

- Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luigi_Gatti_%28restaurateur%29

- Lake’s, June 14 1902, p5. With thanks to Danny Trick and Victoria Sutcliffe of Falmouth RFC for showing me this.

- With thanks to Mr John Jackett of Falmouth for providing me with this article.

- Image from: https://www.crfu.co.uk/home/gallery/. See also: West Briton, March 12 1928, p2.

- Image from: https://imagearchive.royalcornwallmuseum.org.uk/fine-art/run-home-henry-scott-tuke-1858-1929-18975858.html

- Of course, this reading of The Run Home only works if it is indeed Tuke at the helm of the boat. Elsewhere it is asserted that the helmsman is in fact a man called Hingston, a lifeboatman from Falmouth. See: https://imagearchive.royalcornwallmuseum.org.uk/fine-art/run-home-henry-scott-tuke-1858-1929-18975858.html

- Images and information from: https://www.angloboerwar.com/other-information/16-other-information/1844-blockhouses

- For more information, go to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecil_Rhodes, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Beers, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jameson_Raid

- For the soccer match, see the Cornish Echo, October 11 1901, p6. Jackett’s supposed appearance for Transvaal is mentioned in: The Tigers Tale: The Official History of Leicester Football Club 1880-1993, by Stuart Farmer and David Hands, ACL & Polar Publishing, 1993, p154.

- For a brief overview of the various phases of the Boer War, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Boer_War

- For example, the Evening Mail (London), August 28 1901, p6.

- Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Boer_War_concentration_camps

- Find the article here: https://www.cousinjacksworld.com/cornish-mine-workers-in-south-africa/

- See: https://www2.lib.uct.ac.za/mss/bccd/Histories/Kimberley/

- Image from: https://www.angloboerwar.com/unit-information/south-african-units/310-cape-mounted-police?start=2

3 thoughts on “In Search of John Jackett, Part Two: The Artist’s Model & The Coastguard’s Daughter”