(If you missed Part Three, click HERE…)

Reading time: 30 minutes

…the Northern Union is a superior game…

~ John Jackett preaches with the zeal of the converted

I blame the officers of the Rugby Union for the ruin of English Rugby Football.

~ the journalist ‘Rover’ speaks his mind after watching the 1905 All Blacks destroy England1

Making hay

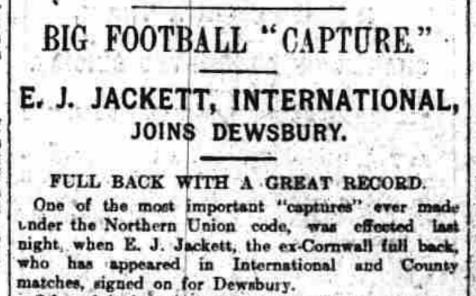

In late 1911, John Jackett was made an offer he couldn’t refuse. Business – we are not told what – put him in contact with the Yorkshire theatre impresario George Smith. Jackett spent several days in the man’s company. When he returned to Leicester, his mind was made up.

Jackett would become manager of the Dewsbury Empire Theatre.

He would also, for an undisclosed fee, sign on for the Northern Union (NU) club Dewsbury2.

The moment he put pen to paper, John Jackett’s Rugby Union career was over. Sportswriters reckoned his time was nearly up anyway:

He is not by a long way the player he was, and probably recognising this himself, he decided to accept a good offer before it was too late – to make hay while the sun shone – and no one can blame him for seizing the chance…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 4 1912, p3

He wasn’t Leicester’s first choice full-back anymore, and younger players were squeezing him out. Plus, Jackett was no longer the gung-ho, hell-for-leather track cyclist who would commit everything to a win, or crash in the attempt. In 1910, we find him officiating a cycle meet in Leicester3.

That same year, he took part in a novelty sprint – against, of all things, a whippet – at a Falmouth meet4. His name was obviously still a draw, but maybe taking part in serious competition was rapidly becoming a thing of the past.

Small wonder, then, that some saw Jackett’s signing for Dewsbury as an attempt to earn some easy appearance money in the fast-approaching twilight of his career.

Perhaps so. But Jackett had probably always done pretty well financially from the amateur game of Rugby Union5. He’d regularly, discretely ‘made hay’ wherever and whenever he could. How else do you explain a Northern ‘paper’s statement that

Other clubs have been in search of Jackett’s services for some time, and he has received tempting offers, but his answer has always been ‘Not for sale’.

Yorkshire Evening Post, December 22 1911, p5

Maybe Jackett wasn’t previously for sale because he’d already been bought. As the Royal Cornwall Gazette wryly observed,

…an above-board deal of this sort is infinitely better than the surreptitious and very tempting bait all too often dangled.

January 4 1912, p3

It’s easy to guess which clubs the Gazette was referring to: Jackett’s most recent Union outfit, Leicester, and Devonport Albion, with whom he had earlier had a season6.

So John Jackett was allowed to ride off into the sunset of his career and earn himself a few (legitimate) bob as a stadium-filler for an unfashionable NU club. Dewsbury hadn’t won a trophy of any kind since 18817.

Admittedly, Cornwall and Leicester were sad to see him go, but ultimately wished him all the best, and no hard feelings8.

Both Cornwall and Leicester thought they knew, and understood, John Jackett. They were forgetting that, throughout the course of his sporting life, he’d singlemindedly dedicated himself to being the best at any game he could turn his hand to.

His devotion to sport had, for certain periods, left him bereft of a regular, or conventional occupation. To be able to join, and play for, the best rugby teams in the land, he’d courted controversy and risked suspension. His drive to succeed was extraordinary.

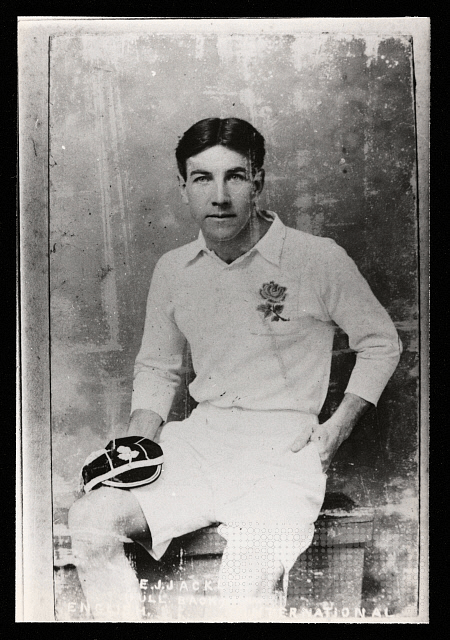

Doubtless realising he wasn’t getting any younger or faster, Jackett craved one last challenge. Track cycling was now beyond him. He’d been the Cornish champion anyway. In Rugby Union, he’d won the County Championship with Cornwall, represented England and toured New Zealand with the (then-named) Anglo-Welsh XV. He even had an Olympic medal.

He’d done all he could in Rugby Union. But laurels, for Jackett, weren’t there to park your backside on. The NU was a new game to master, to win at. In an interview for the Yorkshire Evening Post, Jackett remarked how he had observed his opposite number for Hull KR, who

…is quite the best full-back I have seen…I watched him closely, and now I think I know how to realise my proper function as Dewsbury’s full-back…

February 3 1912, p3

If you want to be the best, learn from the best. Jackett wasn’t just along for the ride. Furthermore,

…I am having to unlearn much of that which I have learnt in the past.

Jackett is completely forsaking his Rugby Union past. He is 100% committed to Dewsbury and the NU.

Granted, in the Post interview he talks fondly of Leicester RFC and Cornwall’s annus mirabilis, 1908. But, like other interviews Jackett gave over the course of his life10, what’s not being said is as important as what he’s saying.

Although his interviewer mentions in passing Jackett’s international career, not once does the man himself touch on his time with England or the Anglo-Welsh tour.

Here we can suggest another reason why Jackett joined the NU: dejection, maybe bitterness, with the RFU and its ethos.

To begin to see why this might be the case, we have to go back to Jackett’s England debut in 1905…

The Crumpled Rose

There’s baptisms of fire, and then there’s making your international rugby debut against the 1905 All Blacks – ‘The Originals’.

They weren’t quite up to the calibre of the legendary 1924 Invincibles11, but only marginally: The Originals only lost one game, against Wales12.

In 35 matches they scored 976 points, and conceded only 59.

They introduced innovative – and controversial – playing positions. The forwards all passed like threequarters, and the threequarters passed like Welshmen. They were all incredibly fit. Hell, they even practised their lineouts.

In other words, they played rugby like a modern XV, and instantly made their opponents look outmoded and Victorian by comparison13. The one thing they lacked was a decent haka:

Before Jackett was selected for England, his Cornishmen had met the Tourists at Camborne RFC in September. The Cornish XV, under Jackett’s leadership, were finally developing into a promising unit, but the All Blacks were something else. They’d marmalised Devon 55-4 days previously; Cornwall, by contrast, had never beaten Devon15.

With a certain degree of inevitability, Cornwall were overwhelmed 41-0, the visitors scoring four goals and seven tries:

Cornwall could not stand the pace. The whole of the second half they had to settle down in their own twenty-five and defend…the brilliant lightning-like flashes of passing, broke Cornwall up…

Western Morning News, September 22 1905, p3

That said, Jackett and his men had shown plenty of grit, and there was no shame in such a result16.

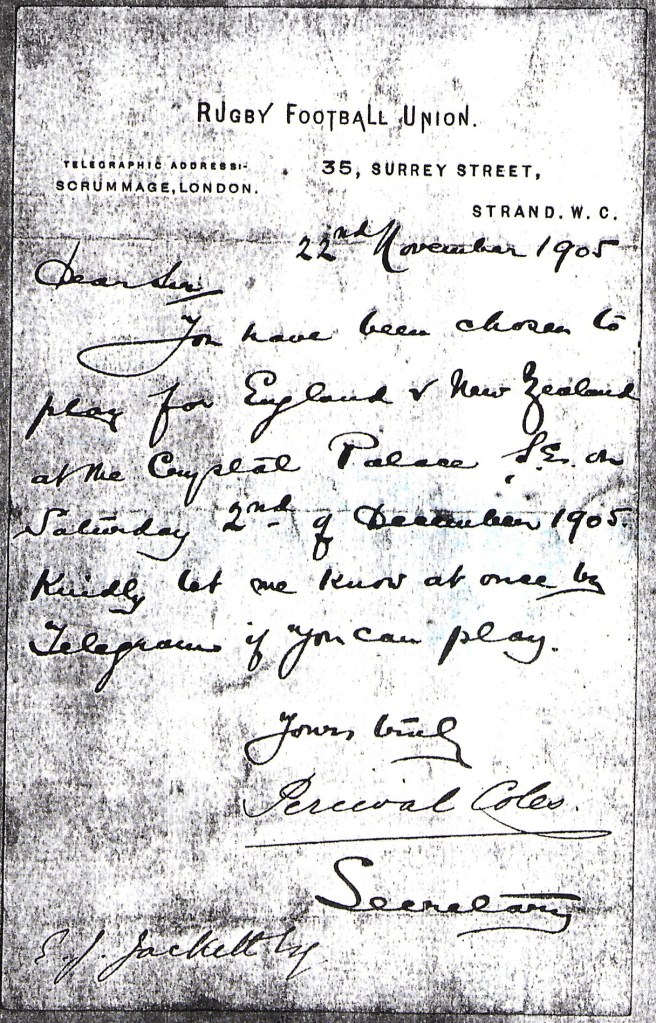

Surely, thought John Jackett as he read of his selection, a XV of England’s best men could match the tourists?

At Crystal Palace, with 100,000 fans (including the future George V) in attendance, New Zealand ran in five tries, winning 15-0.

The beating handed them by the All Blacks was nothing compared to the slaughtering that awaited England in the Press:

England had been an embarrassment:

The score in no way represents the intrinsic superiority of the New Zealanders. One side played practically all the football; the other side played the fool…

‘Rover’, Morning Leader, December 4 1905, p6

Stagnation and conservatism from the top down was the cause of English rugby’s woes:

I blame the officers of the Rugby Union for the ruin of English football. They have tried to keep the game exclusive, they have tried to keep all the plums for public school boys and Varsity men, they have tried to jockey the working man out of the game, and they have nearly succeeded.

‘Rover’, Morning Leader, December 4 1905, p6

Furthermore, ‘Rover’ continued, there had been no attempt to embrace the fast, daring approach of, say, Leicester, Devonport Albion or any club in Wales. England’s only worthy performer on the day was, in fact, a Leicester (and formally Albion) man – John Jackett:

This was the only department in the game where we were superior to the enemy.

‘Rover’, Morning Leader, December 4 1905, p6

Jackett trudged from the field, wearing an All Black jersey:

Though he had acquitted himself well, maybe he was in a reflective mood. Maybe playing at the pinnacle of English rugby wasn’t all it was cracked up to be. His Cornish team of miners and fishermen had surely given a better account of themselves against the All Blacks, yet here he was with men with supposedly better opportunities and backgrounds, who had no stomach for it?

What’s more, Jackett’s new team-mates were predominantly the kind of player the Cornish were desperate to have a crack at. When that chance came in 1908 against Middlesex, Cornwall’s partisan local Press had dismissed them as soft

Varsity men and public school boys, who will probably crack…

West Briton, February 17 1908, p319

But here Jackett was, on the same XV as a bunch of nobs. It can’t have been a comfortable experience.

For English Rugby Union in the early 1900s was a game in the doldrums. The advent of the NU in 1895 had robbed the game of much of its innovation and talent. To add insult to schism, the NU made frequent forays into Union heartlands, acquiring the best talent for itself20.

RFU clubs in turn made a mockery of the Union’s anti-professionalism laws by keeping their top men sweet – and away from the temptations of the NU. Some ‘shamateur’ teams, such as Jackett’s Leicester, were so powerful and valuable to the RFU that the game’s governing body was loathe to call them out in a show of strength21.

Enthusiasm dwindled. In 1895 the English RFU had 416 adult clubs; by 1905 the total was just 15522.

As it was the working-class, Industrial North that had engendered the 1895 split, the RFU’s response was to close its amateur, public-school, Home Counties ranks and shun the working man.

In the Edwardian era, it’s possibly the only thing the RFU undertook with any success. In 1894, 36% of England internationals had working-class backgrounds. Between 1906 and 1910, it was only 13%23.

Class prejudice was endemic in the highest echelons of the game. As one RFU crony remarked, to say that the working man

…knows more about the game than one who has been brought up in the best traditions of the public schools and universities is absurd.

Qtd in Tony Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, Routledge, 2009, p39

This was the kind of atmosphere Jackett would encounter. How you spoke and where you came from was more important than how you played24.

And the play wasn’t great either:

| Opponent | Venue | Date | Result | Score | Game |

| NZ | Crystal Palace | 2/12/1905 | Loss | 15-0 | Test |

| Wales | Richmond | 13/1/1906 | Loss | 16-3 | Home Nations |

| Ireland | Leicester | 10/2/1906 | Loss | 16-6 | Home Nations |

| Scotland | Inverleith | 17/3/1906 | Win | 9-3 | Home Nations |

| France | Parc de Princes | 22/3/1906 | Win | 35-8 | Test |

| S. Africa | Crystal Palace | 8/12/1906 | Draw | 3-3 | Test |

| France | Richmond | 5/1/1907 | Win | 41-13 | Test |

| Wales | Swansea | 12/1/1907 | Loss | 22-0 | Home Nations |

| Ireland | Dublin | 9/2/1907 | Loss | 17-9 | Home Nations |

| Scotland | Blackheath | 16/3/1907 | Loss | 8-3 | Home Nations |

| France | Stade Colombe | 1/1/1908 | Win | 19-0 | Test |

| Wales | Bristol | 18/1/1908 | Loss | 28-18 | Home Nations |

| Ireland | Richmond | 8/2/1908 | Win | 13-3 | Home Nations |

| Scotland | Inverleith | 21/3/1908 | Loss | 21-3 | Home Nations |

| Australia | Blackheath | 9/1/1909 | Loss | 9-3 | Test |

| Wales | Cardiff | 16/1/1909 | Loss | 8-0 | Home Nations |

| France | Leicester | 30/1/1909 | Win | 22-0 | Test |

| Ireland | Dublin | 13/2/1909 | Win | 11-5 | Home Nations |

| Scotland | Richmond | 20/3/1909 | Loss | 18-8 | Home Nations |

Of the thirteen internationals John Jackett played, England won four and drew one. Of these victories, two came against the newest national XV on the block, France, who were only admitted to the Home Nations Championship in 1910, thus making the competition the Five Nations.

When England beat Les Bleus 22-0 in 1909, it was written that

…the play was of a very moderate character…England won easily…but their form scarcely justified such a wide margin.

Leicester Daily Post, February 1 1909, p6

Indeed, an English victory over any side other than France in these years was something of a shock. In March 1906 they regained the Calcutta Cup over a much-fancied Scottish team. Adrian Stoop came into the England XV at the expense of Jackett’s old Falmouth pal, Raphael Jago25, and made the difference.

Jackett also played his part:

He twice stopped what looked like irresistible Scottish rushes, and after the second he got in a kick that developed into a general passing rush by the Englishmen…

Morning Post, March 19 1906, p9

Overall, though, Jackett’s England career was undistinguished, mainly because England were undistinguished too. In 1907 they lost all three Home Nations matches, and won, if that’s the word, the infamous wooden spoon. Jackett played all three matches.

In the final match of 1907 against Scotland, Jackett had to suffer the indignity of having the ball chipped over his head to set up a Scottish try. In happier circumstances, it’s the kind of cheeky move he would have loved to pull himself27.

He also had to contend with an RFU selection policy that would often award a cap to a local player in an attempt to put bums on seats. This happened in 1908 when England lost to Wales 18-28 in Bristol. A Gloucester man got the nod ahead of Jackett28.

In one of his most successful years, 1908, Jackett was bizarrely not picked for England at all. He’d captained Cornwall to the County Championship, won an Olympic Medal, and been selected for the Anglo-Welsh Tour of New Zealand30. But that wasn’t good enough for England.

The nadir was reached in March 1909. For months, Scotland had been refusing to play England. It was a move made in protest at the daily ‘pocket money’ granted the 1905 New Zealanders. Added to this, RFU President Charles Crane had resigned over the impotency of his organisation regarding the Leicester affair. These were dark days for English rugby31.

Somehow, the rift with Scotland was papered over, and the game went ahead. Jackett, in form after England’s first victory in Ireland for 14 years32, was inked in for the Calcutta Cup game. Some expressed surprise at his being the only Cornish selection:

…strange to say, E. J. Jackett is the only one connected with the champion county, Cornwall, considered worth a place…

Manchester Courier, March 9 1909, p3

Scotland came to Richmond and thrashed England 18-8. The Calcutta Cup went back North, as it had done every time Scotland had travelled South for the last 25 years. Jackett was outplayed by his opposite number, and it was his final international33.

Surely his tour to New Zealand in 1908 was more enjoyable?

A very sick animal

To call the 1908 Anglo-Welsh Tour a British and Irish Lions Tour is, to say the least, stretching it a bit. Of course, in 1950 all British Isles tours were retrospectively stamped with the Lions brand, including the 1908 edition. But even at the time, the 28 players selected were hardly representative of the entire British Isles34.

From the get-go,

…strenuous efforts to induce the Scottish and Irish Unions to sanction the inclusion of their players in the side have been futile, and the team will be an Anglo-Welsh combination.

Daily Mirrot, January 3 1908, p14

Scotland and Ireland, still smarting at the liberal amounts of daily spending money permitted the 1905 Originals, boycotted the return tour Down Under. An Anglo-Welsh combination it would have to be, but even then,

Not one of the men would be chosen for a representative British team of to-day; some of the players could not find places in the second team of a first-class Welsh club…

Athletic News (Lancashire), March 9 1908, p1

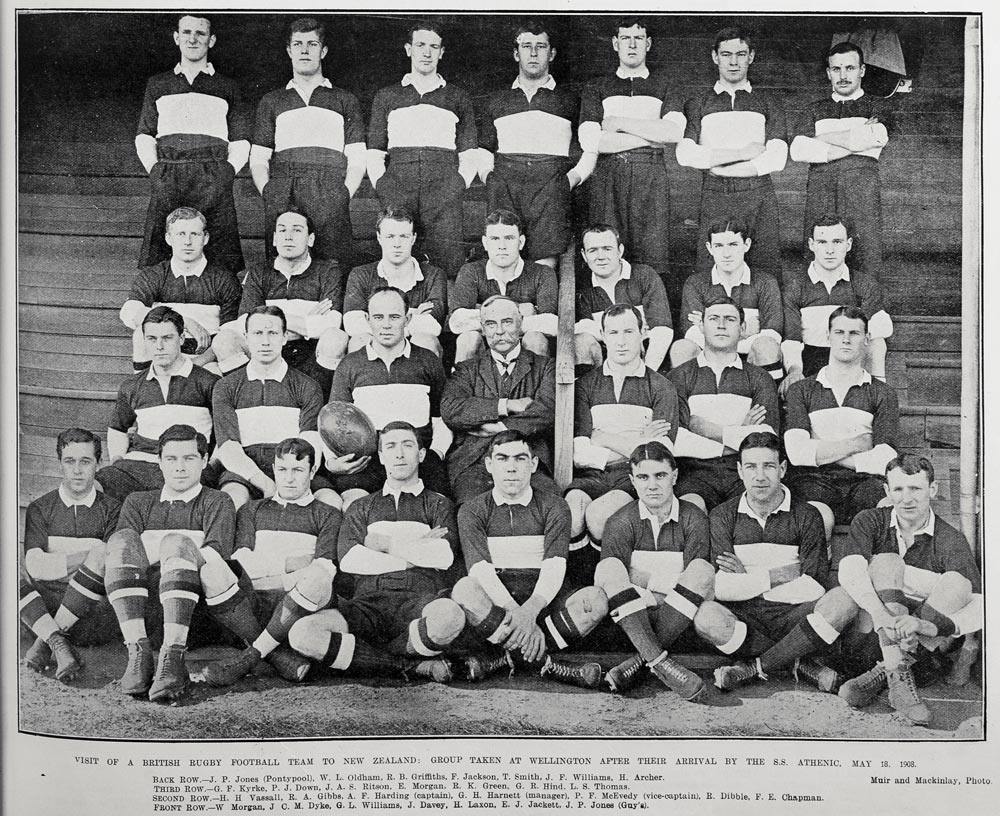

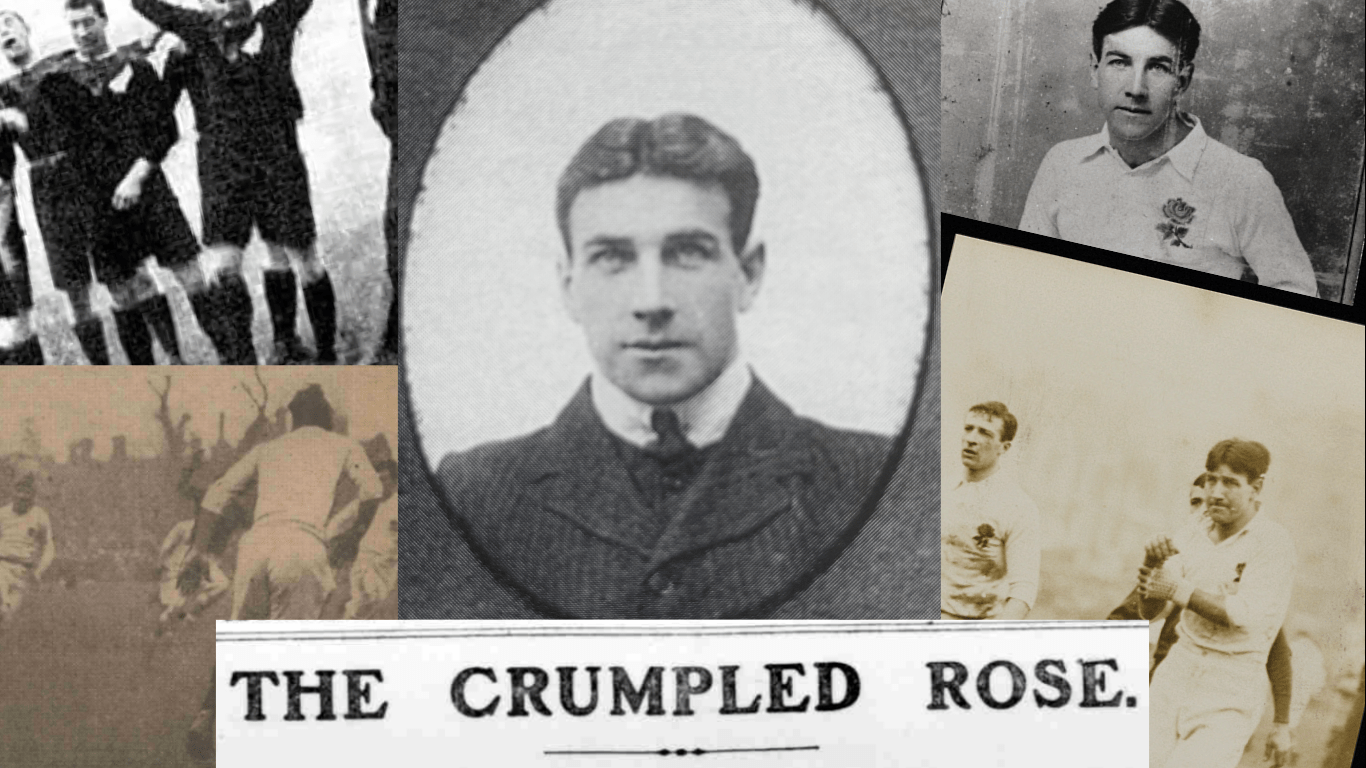

Only 11 members of the touring party were capped internationals. Five players were Old Boys of Christ’s College, Brecon, and there was a man each from Oxford and Cambridge35. At least Jackett had his old mates Maffer Davey and Fred Jackson for company (see image above).

Bearing in mind the all-powerful Lions outfits of modern times, what, if anything, was hoped to be achieved with such a cobbled-together outfit? The official line was announced during the farewell dinner held at The Howard, on The Strand:

…the tour would be of service to the great cause of rugby football…the time was opportune to give assistance to those who were fighting against professionalism in the Colonies…

Sportsman, April 4 1908, p3

A professional All Blacks team operating under NU rules had visited the British Isles in 190737. To spread the increasingly battered gospel of RFU amateurism, a good-will tour of the Antipodes was thought the appropriate remedy.

That’s the official line. It’s obvious many of the players prioritised women, booze and high-jinks above any actual rugby they might play. In fact the 1908 Anglo-Welsh Tour appears to have been undertaken in the best (and worst) traditions of any club team when they’re far away from home.

In New Zealand, however, the following question was asked:

Furthermore, the

…English Union…recognised in football a means of recreation and amusement…Here [New Zealand] there was a tending to regard it chiefly as a sport, and as a means of attracting big gates and big monetary returns.

Evening Post (NZ), May 15 1908, p3

Ne’er the twain shall meet. Recreation and amusement were much in evidence on the Tourists’ voyage:

…they eschewed shipboard training…on the grounds that gentlemen who played the game for its own sake had no reason to prepare for it.

The NZ journalist Ron Palenski, qtd in Tom Mather, Rugby’s Greatest Mystery: Who Really Was F. S. Jackson?, London League Publications, 2012, p33

Stories filtered back of a player dressed as ‘King Neptune’ honouring the Gods of the Ocean by daubing his fellow travellers with a concoction of treacle and flour38.

What the teetotal, fitness-fanatic and dedicated trainer John Jackett made of all this is anyone’s guess. That said, he may have appreciated a break. The tourists sailed on April 3; on March 28, he, Jackson and Davey had been in Redruth, winning the County Championship.

Suffice, when the squad finally arrived, one reporter was unimpressed, remarking on

…the sturdiness of their build gained on the steamer…Some of the men seemed in rather poor condition…

Otago Witness, May 20 1908, p62

By some miracle, the tourists won the opening match against Wairarapa, it being noted that Jackett was

…in brilliant form…

Daily Telegraph (NZ), May 25 1908, p14

Obviously he’d prepared himself in time-honoured fashion.

Storm-clouds were gathering though. Back home, the RFU’s investigation into Leicester was heating up, and rumours were beginning to circulate that Fred Jackson wasn’t who he said he was. The Tour’s evangelistic amateur purity was immediately put under strain, and the very point of sending such an outfit to a land where shamateurism was rife was also brought into question39.

Surely the only riposte was for the Tourists to do their talking on the pitch?

At Dunedin in the First Test, in front of 19,000 spectators, they went down 32-5. The All Blacks ran in seven tries. If modern scoring regulations were in force, the result would have read 46-7. But in any context, that’s a beating41.

By half-time the hosts led 21-0, and

…from this stage onwards there was little interest in the result.

New Zealand Times, June 8 1908, p5

The Anglo-Welsh XV were utterly overwhelmed:

…the lion was a very sick animal indeed.

New Zealand Times, June 8 1908, p5

If the All Blacks’ haka was, to our eyes, lacklustre, the Tourists’ response of crying ‘hip-hip-hooray!’ was as laughable as their play42.

There was one shining light: John Jackett. His kicking, tackling and general industry ensured the All Blacks were unable to push their dominance even more44. As the tour progressed, his reputation was enhanced:

…the inclusion of Jackett as fullback will give additional interest, as his performance in the position is said to be quite a revelation.

Colonist, June 20 1908, p2

Another ‘paper revelled in his “eccentric genius”45.

Not so the rest of the party, whose pathological adherence to the amateur ideal hamstrung them at every turn. In an early match against Wellington, they played most of the game with 14 men after Jackett went off injured. The offer of a substitute (legal in New Zealand) by the hosts was refused. This happened again in the final match of the tour, when even the crowd exhorted the stubborn Britishers to field a replacement, but to no avail46.

The New Zealand public recognised the shortcomings of their visitors, one fan even going so far as to suggest playing an uncapped XV for the Second Test, thus ensuring a more palatable spectacle47.

The All Blacks did field a weaker team second time round. A 3-3 draw was the result, but the home XV could have won, were it not for

…Jackett, who kicked the ball amongst the spectators, robbing the Blacks of a seemingly certain try.

Colonist, June 29 1908 p2

Normal service was resumed for the Final Test, where the All Blacks dished out a 29-0 thrashing.

By this stage, the Anglo-Welsh party was a shambles. Two unidentified members went fishing on a boat which capsized. Jackett himself, with the aid of two All Blacks, put the experiences of a lifetime to good use by saving another player from drowning, then seems to have started a mischievous rumour about himself going to work for the New Zealand Tourist Board. Their interests in the fairer sex were sardonically observed, with one player, Vassall, missing the boat to Australia on account of these extracurricular activities48.

The Tourists also complained bitterly about the All Blacks’ rough play, and accused them of outright cheating49.

Worse still, their image as paragons of amateur virtue had been destroyed. Gossip columnists reckoned at least one Anglo-Welshman had been clandestinely recruiting for the NU whilst in New Zealand50, and Fred Jackson had been recalled home to face the RFU’s music. He sailed on June 2651.

He never returned to England.

As a result of the RFU’s investigations into Leicester RFC, it became apparent that ‘Fred Jackson’ had played NU for Swinton, under the alias John Jones. In fact, the man’s real name was Ivor Gape, and he was neither Cornish, nor English, but Welsh. Rather than sail home, he jumped ship, settled in New Zealand and eventually represented the All Blacks NU side. He died in 195752.

Jackett watched his old Cornwall and Leicester comrade sail off, and was so overcome team-mates had to lead him away53.

Which raises an interesting point. Why would Jackett be upset? After all, he’d surely see Jackson again in England? Jackett’s grief only makes sense if he knew Jackson had no intention of returning home: Jackett knew he’d never see his friend again. And if Jackett knew that, what else did he know of Jackson’s story?

We can speculate that Jackson had taken Jackett into his confidence: Jackett knew Jackson had played for the NU, and that ‘Fred Jackson’ wasn’t in fact his real name. And if Jackett knew that, he would have also been aware that, in playing with Jackson for Leicester, he had knowingly professionalised himself.

All of which makes his following statement ring rather hollow:

Any suggestions which are made reflecting upon the amateur bona fides of the club are, you can take it from me, most unjustifiable.

Yorkshire Evening Post, February 3 1912, p3

For the rest of his life, John Jackett never publicly uttered a word about Fred Jackson. He would have also known that, if Jackson was in hot water at Leicester, then he probably was too.

*

Despite being the Anglo-Welsh Tour’s sole success, Jackett was only to represent England on four more occasions.

His approach to the game, his methods and outlook, a lack of public school polish, allied to the questionable activities of his club, Leicester, perhaps meant his face didn’t fit with the RFU.

Maybe Jackett suspected, or realised this. He could have gone quietly and ended his playing days at Leicester. But not John Jackett. Nor Fred Jackson.

One final slap in the face sent him to Dewsbury.

Fry’s

It may not surprise readers to learn that Jackett was something of a rugby theorist. He contributed an article on threequarter play to a New Zealand ‘paper, and shows how deeply he thought about the game, how serious his approach was54.

It would have also put him at odds with the Rugby Establishment.

First off, Jackett emphasises “systematic training” for his threes in various key areas. For cast-iron amateurs, ‘training’ was a dirty word.

The best threequarters he’d seen in action (and Jackett by 1908 had seen them all), were the Welsh:

…the best and cleverest players in the world…in my opinion the Welsh three-quarters cannot be beaten.

Evening Star (NZ), January 13 1908, p8

He also identified the Welsh centre Gwyn Nicholls55 as the “finest the world has ever seen”.

Nicholls wasn’t selected for the Anglo-Welsh Tour.

Contrast that with his opinion of England’s outsides:

English players do not study the game sufficiently. They are not serious enough in their efforts…

For ‘serious’, read ‘professional’. Jackett outlined a thorough training programme (speed, swerving, tackling, punting, following-up, judgment), as well as recommending the back-line formation pioneered by the All Blacks – and to start coaching said formation to youngsters, thus “inculcating the idea into their minds”.

As Jackett’s article goes on, it becomes a critique of English rugby’s methods:

English rugby footballers were inferior to the All Blacks…because they were not so fast…[they] are lacking in judgment. They have no plan of action…

Jackett concludes by wishing that

If only the English ‘outs’ could practice together and there was not so much changing in the composition of the team, England would have done far better in the past.

Systematic training methods, youth development, consistency in selection. But the RFU were never going to listen to John Jackett. Adrian Stoop had similar ideas to his, and being as Establishment (Rugby School, Oxford University, Harlequins) as they come, he could finally start to change the system from within56.

Jackett saw his ideas and criticisms ignored, as were his captaincy skills. Had he not whipped an unfancied bunch of Cornishmen into being the best in the land? What might he have done in charge of England?

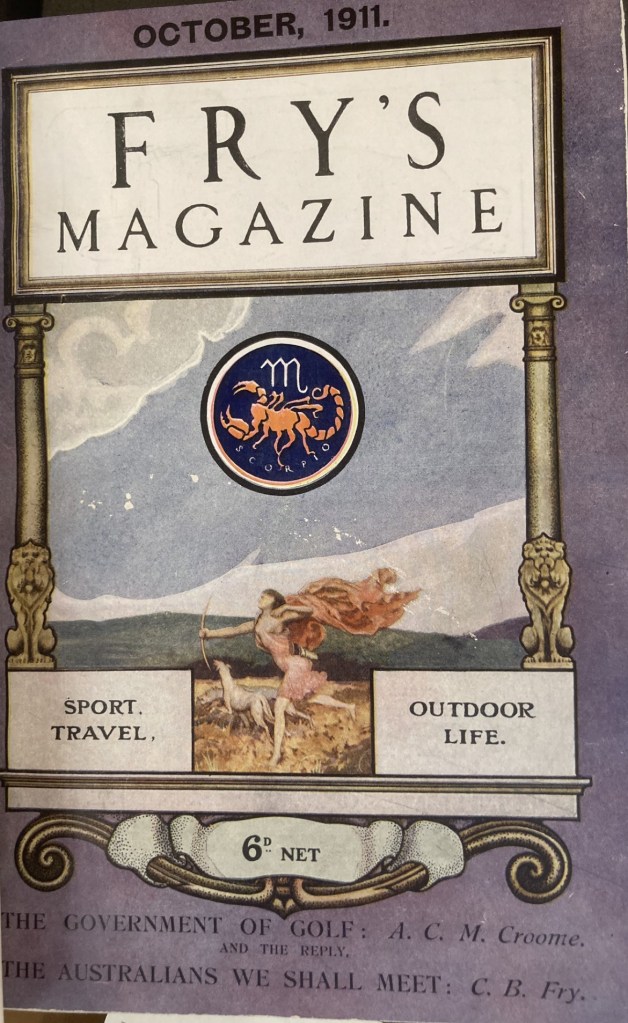

The article he produced on full-back play in October 1911 for C. B. Fry’s Magazine was far from ignored58. Jackett was widely condemned for the writing the following:

Always remember that you can better get and hold a ball that has bounced…

Fry’s Magazine, October 1911, p47. Bodleian Library, Oxford

Jackett appears to be advising full-backs to not catch the ball in the air, but to rather wait for it to bounce before fielding it. This practice, as anyone will tell you, is rugby suicide.

How they lined up to shoot him down:

…the practice is condemned…the man who is uncertain about a catch or who ‘funks’ it by waiting for the drop is rightly regarded as not being up to his game…

Morning Leader, October 4 1911, p6

Jackett suddenly had a

…fatal obsession for ‘waiting for the bounce’ – the worst of all faults in a full-back.

Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 4 1912, p3

However, his critics were misreading, or ignoring Jackett’s text:

Of course there will be many times in a match when you cannot allow the ball to bounce…the opposing men may be too near you, or the screw on the ball may make you not at all certain which way it would turn after bouncing…

Fry’s Magazine, October 1911, p47. Bodleian Library, Oxford

Before the article appeared, Jackett had been noted as a full-back who, if he could help it, didn’t allow the ball to bounce. Indeed, the earliest recorded instances of him playing rugby note his safe pair of hands when dealing with the high kick59. The reaction to the Fry’s article damaged his reputation.

Jackett rightly took up the cudgels:

I have been wrongly quoted…It is true that the ball is easier to take from the bounce, but that involves a delay in fielding which may be fatal, and, therefore, I say always go for the ball before it bounces.

Yorkshire Evening Post, February 3 1912, p3

They wouldn’t listen to him. They twisted his words. They wouldn’t take him seriously. They wouldn’t pick him. They thought he was finished. And, most risible of all for an arch-competitor like Jackett, England kept losing.

Small wonder he jacked it all in for the NU.

A light of other days

Jackett wasn’t exactly joining a top NU outfit. In the 1910-11 season, Dewsbury finished a middling tenth in the League. Silverware was a memory from the 1880s60.

All that would change with the big-name signing of John Jackett. He was making his mark as early as December 1911, kicking three goals in a victory over Wakefield Trinity61. His presence certainly “heightened interest”62, and he enjoyed a certain media attention:

Jackett himself was an enthusiastic participant. The NU game is

…the more open, and the one in which there is less time wasted; therefore, it must be a better game from the spectators’ point of view.

Yorkshire Evening Post, February 3 1912, p3

It was later heard in Cornwall that Jackett believed the NU game “superior” to Rugby Union63. He demonstrated this in deeds as well as words: there are reports of him recommending Union players for Dewsbury to tempt North64.

John Jackett was not a man to do things by half. In the Second Round of the 1912 Challenge Cup at Salford (a close-run 9-8 victory for Dewsbury in front of 16,000), he “outshone” his younger, faster opposite number65.

Coming second to Jackett that day was Harry Launce (or Lance), who had joined Salford in August 1911 from Camborne RFC. It would be fascinating to know what they said to each other.

In the Quarters, Dewsbury came through 5-2 against Batley. Jackett’s kicking for once was off, but his tackling was “always deadly”. His team were having a good run, but this year Oldham were tipped to win overall67.

18,000 watched the Semi at Dewsbury’s ground, Crown Flatt (now the FLAIR Stadium). Jackett may have been pushing the years, but he knew when to put his body on the line: a try-saving tackle meant his team beat Halifax 8-568.

20,000 watched the Final in Leeds, as Dewsbury faced the favourites, Oldham. Lancashire against Yorkshire in the Challenge Cup Final – it doesn’t get bigger. At half-time, Dewsbury led 5-2. Only Jackett’s last-ditch tackling was keeping them ahead.

And then, all the years of single-minded dedication and practice paid off. Jackett slammed a monster kick deep, deep into OIdham’s half, sparking a mad scramble back. It was the kind of kick defending teams hate, and it pushed Oldham perilously close to both the touchline, and their own tryline.

John Jackett, past it? Not on your life. He could still gift his set of forwards a dream position when it was asked of him.

Oldham failed to clear up, and Dewsbury scored. For the first time in their history, they had won the Challenge Cup. They wouldn’t repeat the feat until 1943, and haven’t won it since69.

Sadly, Jackett’s playing time with Dewsbury was short. Even at the start of the 1912-13 season, he was described as

…a light of other days…

Yorkshire Evening Post, September 13 1912, p3

A broken jaw suffered against Coventry in October 1912 kept him out for six weeks. It was the beginning of the end71.

Being John Jackett, he didn’t go quietly. Controversial to the last, he requested a transfer when a satisfactory explanation regarding his non-selection for a game in March 1914 wasn’t forthcoming72.

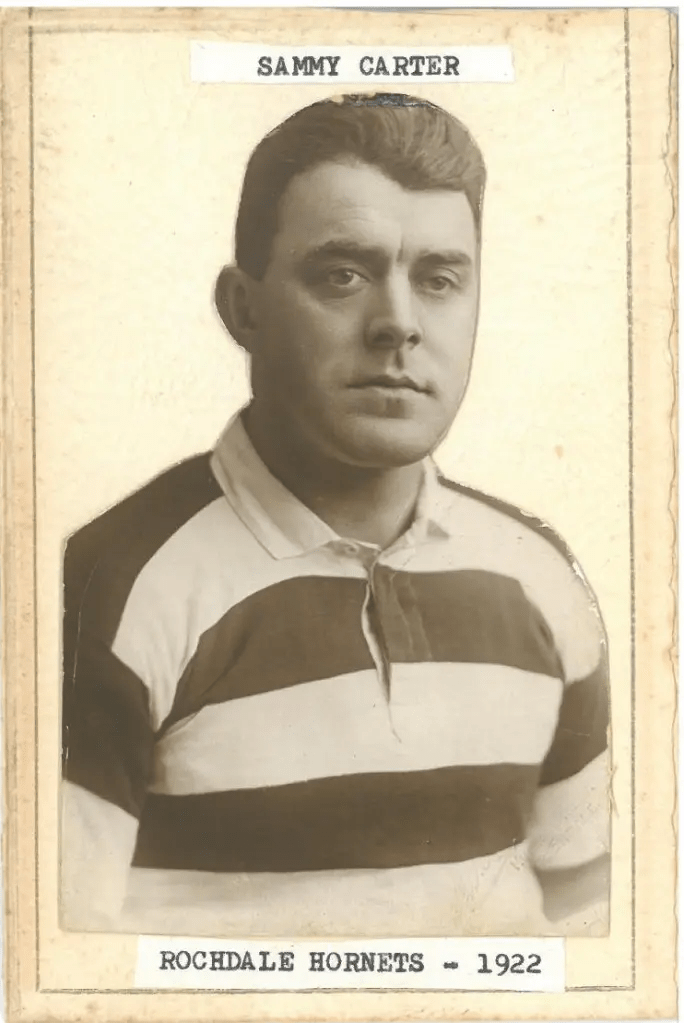

His ever-burgeoning theatre commitments, allied to his age, meant his appearances for Dewsbury became ever-more sporadic. One of his final games was against Rochdale Hornets, where he came up against another Camborne and Cornwall player, Sam Carter73.

By early 1915, it was all over75. A lifelong dog-lover, Jackett switched his energies to his beloved Chows, winning prizes at Crufts in the early 1930s76. He also gained a reputation as a selfless coach of young rugby players77.

Finally, people listened to his wisdom.

The King of Cornish Sport

At time of writing, only seven men have represented the British Lions and won the Rugby League (or Northern Union) Challenge Cup. If we allow for the obvious qualifications regarding the 1908 Anglo-Welsh Tour (and the British Lions website certainly does78), then John Jackett was the first. As you can see above, this puts him in a pretty exclusive club.

Of the seven, only two of them, Jackett and Tosh Holliday, captained County Championship winning XVs. Holliday took Cumberland & Westmorland all the way in 192479. Only Jackett has won an Olympic Medal. His achievements are truly extraordinary.

In purely Cornish sporting terms, these accolades surely put him head and shoulders above any other sportsman Cornwall has produced. If you include his early, pioneering prowess as a track cyclist and athlete, then you can say with some confidence that John Jackett was the best there ever was, the

King of Cornish Sport.

Complex, controversial, intelligent, outspoken, single-minded, competitive, talented, individualistic yet a born leader, John Jackett died in Middlesborough in 1935.

A man who knew him said he had dedicated his

…heart and soul…

Leicester Evening Mail, November 13 1935, p6

…to rugby football.

Unsurprisingly, a racehorse was named after him. Equally unsurprisingly, the ‘John Jackett’ proved very successful, setting a world record time for a hurdle race in Manchester80.

John Jackett – what better name for a thoroughbred?

With special thanks to: Danny Trick and Victoria Sutcliffe, Falmouth RFC; Mr John Jackett of Falmouth; Professor Tony Collins; Adrian Ellard, Cape Town; Richard Pascoe, St Piran Pro Cycling; Donna Westlake, Falmouth Town Council; Dewsbury Rams RLFC; Dr Sharron P. Schwartz, Exeter University; Phil Westren, Cornish Pirates RFC; David Fuge, Plymouth Albion RFC; Mark Warren, Camborne RFC, and many more.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Excerpts from: West Briton, January 15 1914, p3; Morning Leader, December 4 1905, p6.

- Yorkshire Evening Post, December 22 1911, p5. The Dewsbury RLFC official history (chapter 6) witholds Jackett’s fee.

- Leicester Evening Mail, October 16 1910, p6 and the Leicester Daily Mercury, November 22 1911, p6. For more on Jackett’s cycling exploits, see: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/06/29/in-search-of-john-jackett-king-of-cornish-sport-part-one/

- Cornish Echo, August 12 1910, p7.

- See: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- See: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- For more on Dewsbury Rams, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dewsbury_Rams

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 4 1912, p3; Leicester Daily Mercury, November 22 1911, p6.

- Image from the Dewsbury RLFC official history, chapter 6.

- Witness the two where he touches on his time in South Africa: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/06/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-two-the-artists-model-the-coastguards-daughter/

- Played 32, won 32. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1924%E2%80%9325_New_Zealand_rugby_union_tour_of_Britain,_Ireland_and_France

- A game that was billed as ‘The Match of the Century’: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Match_of_the_Century_(rugby_union)

- The All Blacks employed a ‘rover’, an early version of a wing-forward. All their pack had allocated scrummaging positions – in the British Isles, it was still ‘first up, first down’. In the outsides, instead of a left and right half-back style (where modern scrum- and fly-half duties are alternated), the All Blacks had a dedicated scrum-half, with the 10 and 12 combining for a more defensively solid five-eighth formation. For more on The Originals tour, including results, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Original_All_Blacks

- Image from: https://www.theoffsideline.com/remembering-1905-originals-overcome-icy-edinburgh-reception/

- See: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- In 1906, Jackett’s men held the South Africans to 9-6 in Redruth: Cornishman, December 27 1906, p5. At Camborne in 1909, the Australians beat a Cornwall minus Jackett 18-5. His absence was “badly felt”: Western Echo, October 10 1908, p3.

- Image from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:England_rugby_team_1905.jpg

- See: https://www.falmouthpacket.co.uk/news/17669461.john-jacketts-1905-new-zealand-blacks-top-auctioned-off/

- See In Search of John Jackett, Part Three: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- The effects of this on Cornish rugby can be seen in my post on the subject here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/02/03/the-great-cornish-rugby-split/

- See In Search of John Jackett, Part Three: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- Figures from: Tony Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, Routledge, 2009, p39.

- Tony Collins, A Social History, p39.

- For more on this period, see: Tony Collins, A Social History, p22-46, and his Rugby’s Great Split: Class, Culture and the Origins of Rugby League Football, Frank Cass, 1998. Also, James W. Martens, “They Stooped to Conquer: Rugby Union Football, 1895-1914”, Journal of Sport History, Vol. 20.1 (1993): p25-41.

- See In Search of John Jackett, Part Three: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- For more on Peters, see: https://www.skysports.com/rugby-union/news/12321/12717311/james-jimmy-peters-the-tragic-and-turbulent-story-of-englands-first-black-rugby-player

- Morning Leader, March 20 1907, p8.

- Leicester Daily Mercury, January 1 1908, p3.

- Image from: https://www.tate-images.com/MB8825-Photograph-of-Johnny-Jackett-wearing-his-England.html

- See In Search of John Jackett, Part Three: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- Daily Mirror, February 1 1909, p14, and In Search of John Jackett, Part Three: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- Daily Mirror, February 15 1909, p14.

- Morning Leader, March 22 1909, p6.

- For more information, see: https://www.espn.co.uk/rugby/story/_/id/18778556/1908-lions-tour-new-zealand-unmitigated-shambles, https://www.lionsrugby.com/2010/01/25/the-lions-down-under-1908/, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1908_British_Lions_tour_to_New_Zealand_and_Australia

- Information from: https://www.espn.co.uk/rugby/story/_/id/18778556/1908-lions-tour-new-zealand-unmitigated-shambles

- Image from: The Tigers Tale: The Official History of Leicester Football Club 1880-1993, by Stuart Farmer and David Hands, ACL & Polar Publishing, 1993, p20.

- Tony Collins, Rugby’s Great Split, p218-24.

- Tom Mather, Rugby’s Greatest Mystery: Who Really Was F. S. Jackson?, London League Publications, 2012, p31.

- Athletic News (Lancashire), June 1 1908, p1.

- Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1908_British_Lions_tour_to_New_Zealand_and_Australia

- Daily News (London), June 8 1908, p2, and New Zealand Times, June 8 1908, p5. In 1908, a try was worth 3 points, a conversion 2. The All Blacks converted four of their tries, and kicked a 3-point penalty.

- From: https://www.espn.co.uk/rugby/story/_/id/18778556/1908-lions-tour-new-zealand-unmitigated-shambles

- Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1908_British_Lions_tour_to_New_Zealand_and_Australia

- Daily News (London), June 8 1908, p2, and New Zealand Times, June 8 1908, p5.

- New Zealand Times, June 6 1908, p5.

- Lyttleton Times (NZ), May 28 1908, p7; Otago Witness, July 20 1908, p62.

- Evening Post (NZ), June 13 1908, p2.

- Colonist, June 20 1908, p2; New Zealand Observer, July 4 1908, p7; Otago Witness, August 5 1908, p31; New Zealand Truth, August 29 1908, p3; Observer (NZ), August 29 1908, p10. Jackett knew rather a lot about saving men at sea: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/06/29/in-search-of-john-jackett-king-of-cornish-sport-part-one/

- Oamaru Mail, July 24 1908, p4; Observer (NZ), August 1 1908, p3.

- New Zealand Truth, July 11 1908, p3.

- Feilding Star, June 27 1908, p2.

- Tom Mather, Rugby’s Greatest Mystery: Who Really Was F. S. Jackson?, London League Publications, 2012.

- Leicester Daily Mercury, August 15 1908. p5.

- Evening Star (NZ), January 13 1908, p8.

- For more on Nicholls, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gwyn_Nicholls

- For more on Stoop, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adrian_Stoop

- Image from: https://www.tate-images.com/preview.asp?item=MB8807&itemw=4&itemf=0001&itemstep=1&itemx=28

- Jackett probably knew Fry through Henry Scott Tuke; the artist was friends with the eminent cricketer. See In Search of John Jackett, Part One: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/06/29/in-search-of-john-jackett-king-of-cornish-sport-part-one/. The two sportsmen had much in common. Fry was a driven, multi-talented crack (England cricket captain, FA Cup Finalist, long-jump specialist) who also worked as a nude model in times of financial stress. His Magazine is a high Edwardian cultural touchstone on matters such as sports, games, gentlemanly pastimes and even childrens’ toys. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C._B._Fry

- Jackett’s safe catching is noted in Athletic Chat, March 10 1909, p11. Going further back, it’s also observed in Lake’s Falmouth Packet, March 3 1897, p3. See Part Three, https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/

- Dewsbury RLFC official history (chapter 6); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dewsbury_Rams

- Yorkshire Post, December 26 1912, p3.

- Hull Daily News, December 23 1912, p6.

- West Briton, January 15 1914, p3.

- Yorkshire Evening Post, September 27 1913, p5. Courtesy Mark Warren, Camborne RFC.

- Athletic News, March 4 1912, p6. Dewsbury had enjoyed an easy win in Round One over Lane End Utd. Yorkshire Post, February 19 1912, p4.

- For more on Launce, and other Cornishmen who joined the NU, see my post on the subject here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/02/03/the-great-cornish-rugby-split/

- Yorkshire Post, March 25 1912, p3.

- Yorkshire Post, April 15 1912, p4.

- Star Green ‘un, April 27 1912, p5; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dewsbury_Rams

- Image from: http://www.arthurlloyd.co.uk/DewsburyTheatres.htm

- Yorkshire Evening Post (p8), and Hull Daily Mail (p2), December 8 1912.

- Yorkshire Post, March 7 1914, p16; Yorkshire Evening News, March 14 1914, p5.

- Jackett’s increasing theatrical involvement is noted in the Yorkshire Evening Post, November 21 1914, p4. That he played against Carter is noted in the Rochdale Observer, April 4 1914.

- For more on how Carter came to join the NU, see: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/02/03/the-great-cornish-rugby-split/

- Yorkshire Evening Post, January 16 1915, p6; Hull Daily Mail, February 10 1915.

- Leeds Mercury, February 14 1931, p5.

- From Jackett’s obituary: Leicester Evening Mail, November 13 1935, p6.

- See: https://www.lionsrugby.com/2010/01/25/the-lions-down-under-1908/

- For more on Holliday, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Holliday_(rugby), and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cumbria_Rugby_Union

- Leeds Mercury, November 13 1935, p13.

This was a useful overview of the topic.

LikeLike