Reading time: 20 minutes

The real and only test of a good prison system is the diminution of offences by the terror of punishment…as monotonous, irksome, and dull as possible…no work but what was tedious, unusual, and unfeminine…to keep the multitude in order, and to be a terror to evil-doers…

~ The Reverend Sydney Smith, 1822

“Step in young man, I know your face, It’s nothing in your favour, A little time I’ll give to you: Six months unto hard labour.”

~ The Treadmill Song1

The Penitentiary Act of 1779 was the Government’s response to reformer John Howard’s 1777 report The State of the Prisons. Independently-run jails were found to be unsanitary sinks of vice and corruption. If you couldn’t afford to buy decent food from the easily-bribed turnkey, you would probably starve to death. That’s if typhus didn’t claim you first.

Either clapped in irons all day or lying in cramped, unlit communal cells swarming with vermin, small wonder the prisoners sought refuge in sex, alcohol and violence (so did their jailers). Although in practical, state prison-building terms, the Act was largely a failure, combined with Howard’s work it generated public debate and opened the way toward prison reform3.

The debate centred around the following question: what are we going to do with them all? You couldn’t transport convicts to North America anymore, though New South Wales was looking promising. Also, public opinion was beginning, on the whole, to turn against executions too except for the most serious crimes. Though what has retrospectively become known as ‘The Bloody Code’ demanded death for over two hundred offences by the late 1700s, judges regularly declined to don the black cap, a practice that led to the more lenient 1823 Judgment of Death Act4.

Two social groups were prominent in the debate on this new era of penal punishment. The Evangelicals, centred around the Quaker Elizabeth Fry, argued that the convicted criminal ought to be reformed through the application of solitude and clean-living piety. The Utilitarians (simply, a group of theorists that encouraged actions leading to the greatest good for the greatest number), led by Jeremy Bentham, wanted prisoners to be productive and simultaneously provide a deterrent to others5.

Both groups agreed that they

…did not want less punishment…but more refined and effective punishment.

U. R. Q. Henriques, “The Rise and Decline of the Separate System of Prison Discipline”, Past and Present, Vol. 54 (1972), p63

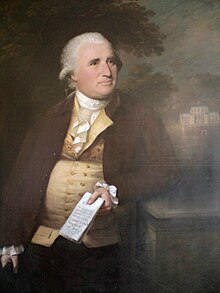

One man heavily influenced by the findings and recommendations of Howard, the Evangelicals and the Utilitarians was Sir John Call (1731-1801), an engineer and politician from Devon. The jail he designed and had built on Berrycombe Road, Bodmin, by 1779 was seemingly conceived with the reformers’ specifications in mind7.

When John Howard visited in 1784, he certainly approved. Each prisoner had a separate cell for personal reflection, there were baths, an infirmary, the inmates (segregated by gender) earned a percentage of their labours sawing or polishing, and liquor was strictly verboten. Howard wrote that

By a spirited exertion, the gentlemen of this county have erected a monument of their humanity, and attention to the health and morals of their prisoners.9

By 1812, the jail was a pious, bustling site of industry. Another reformer, James Neild (1744-1814) paid a visit. He described the “orderly and devout” nature of the inmates during Divine service, and during daylight hours

The Women card and spin wool, or make, mend and wash the other prisoners’ clothes and bedding. The Men are chiefly employed in sawing timber…or in sawing and polishing head-stones for church-yards; or else in weaving at the looms…11

Neild further mentioned that those in prison for debt kept what money they earned; the rest, half. He was informed that one convict had learnt the trade of sawyer during his enforced stay, and was now earning good money on the outside.

In the early 1820s, the Committee of the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline observed similar:

At Bodmin, the employments of the prisoners are thrashing, and grinding corn, sawing and polishing stones for chimney-pieces, flooring, tombstones, &c; also making clothing, shoes, and blankets. The females are employed in spinning and knitting, making and mending, and washing clothes for themselves and the male prisoners.

Public Ledger, October 5 1821, p1

And this was the problem: the Industrial Revolution witnessed inside the many prisons of the land, and not just Bodmin’s, was having an adverse affect on the Revolution outside. Convicted felons could produce goods cheaper than their more honest counterparts, plus

…if prisoners became more industrious and were seen to prosper, gaols would cease to be dreaded.

U. R. Q. Henriques, “The Rise and Decline of the Separate System of Prison Discipline”, Past and Present, Vol. 54 (1972), p67

And, if jails became more like apprentices’ workshops, crime would surely rise, and prisons overcrowd, as more people would seek to gain a bed, food and learn a trade inside a prison’s welcoming walls. Suddenly, public opinion swung back to the notion of actually punishing those who had broken the law. Which is precisely why the Quaker-dominated Committee of the Society for the Improvement of Prison Discipline was visiting jails in 1821: to increase discipline:

The efficacy of such a system of hard labour on the minds and habits of an offender has not, even yet, been generally tried, or fully appreciated, in this country; but where the experiment has been fairly made, the benefits have been most striking. Few who have been subjected to this species of punishment, regard imprisonment without terror…

Public Ledger, October 4 1821, p1

The same question was being asked in 1821 as in 1779: what are we going to do with them all? The answer now was, to make them bitterly regret transgressing the laws of the land. But how?

Enter engineer William Cubitt (1784-1861), and his latest invention: the treadwheel.

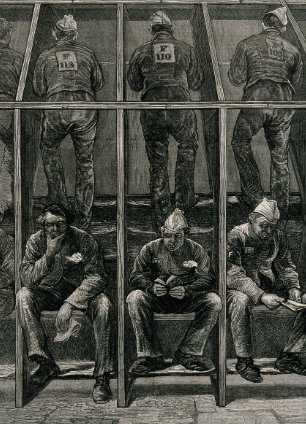

Cubitt’s device was simple. An iron frame held a large hollow cylinder of wood, around which was a series of steps about 7-8″ apart. Depending on the size of the ‘wheel (and the capacity of the jail in which it operated), between five and thirty prisoners could endure it at any given time, separated by boards and compelled to tread uphill in silence. As the felons walked forward, the ‘wheel would revolve, weights and machinery ensuring each would take their steps in turn.

If judged medically fit at the start of each day, a prisoner sentenced to hard labour would tread the wheel in 15-minute stints, with a 5-minute break…for six hours13.

Each day, inmates would be climbing between 7,500ft and 8,640ft, or 1.4 to 1.6 miles. That’s pretty much to the top of The Shard. Some treadwheels were deployed constructively. One such in Gloucestershire was used to grind corn, another in Lancashire was attached to a loom and produced cloth. These were the exceptions16.

Bodmin’s treadwheel was ordered in 1822, to be erected in the Bridewell Yard. This, going by what we know of the prison layout of the time, situated it close to the day-rooms of the male prisoners17. It was still under construction when a law student visited that year, who noted it was to have a capacity of ten, but was not yet

…applied to any useful purpose.

Thoughts on Prison Labour, by a Student of the Inner Temple, London, 1824, p117. Retrieved from Google Books

When up and running, it wouldn’t grind corn, or produce cloth. No, at Bodmin, its

…purpose was much more sinister.

David Freeman, Bodmin Jail: Bridewell Revisited18

Its job was to mentally and physically crush those unfortunate enough to be subjected to it. Your monotonous, silent, solitary toil was, in practical terms, utterly pointless. In fact, it bordered on torture, and thus carried with it a vestige of earlier, bloodier methods of punishment, as one historian has realised:

…a punishment like forced labour…has never functioned without a certain additional element that certainly concerns the body itself…imprisonment has always involved a certain degree of physical pain…there remains, therefore, a trace of ‘torture’ in the modern mechanisms of criminal justice…

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, Penguin, 1991, p13-14

Foucault may have been far removed from the nature of the treadwheel when he wrote in the 1970s, and was indeed considering hard labour per se, but at the time, controversy raged as to the effects of the ‘wheel on the prison population.

Horror stories began to emerge. The treadwheel wasn’t merely disciplining and punishing prisoners.

It was killing them.

It is a hideous irony that, a device introduced as part of the extended (and largely ad-hoc) programme of penal reform was in turn attacked by the reformers themselves. An anonymous London law student visited many jails, and in 1824 produced, much as John Howard had back in 1777, an excoriating account of the country’s prison system, in particular the employment of the treadwheel. Thoughts on Prison Labour is now available on Google Books, but its more sensational passages were serialised in the reformist, democratic newspapers of the day, notably the then-weekly Liverpool Mercury.

The editorial introducing the extracts made it plain:

…at the very time when the British are interesting themselves…on behalf of their suffering fellow subjects in the West Indies, they should permit an instrument of torture to be erected under their own eyes, which exceeds the severities there exercised in an incalculable degree…

Liverpool Mercury, May 21 1824, p7

The Mercury is referring to the Slave Trade Act of that year, which would be granted royal assent in June, and further reinforced the abolitionist movement. The editorial, therefore, is accusing the British people of hypocrisy: they can abolish slavery on the one hand, yet condone torture with the other19.

Furthermore, use of the treadwheel was “illegal” and “inconsistent with the law”20. Perfectly acceptable (and suitably exhausting) forms of hard labour had existed previously, wrote the law student, but this new

…penal machine…[has] been introduced WITHOUT THE EXPRESS SANCTION OF THE LEGISLATURE…a mode of punishment to which every individual…is liable…ought not to be established, without the consent of the people through their representatives…

Qtd in Liverpool Mercury, May 21 1824, p7

To arbitrarily introduce such an unprecedented instrument of punishment was undemocratic and unconstitutional. The magistrates who ordered the ‘wheels, and their manufacturers, however, could only see the profit.

By 1823, there were twenty-three treadwheels in operation; models had also been sent to Dublin, to Russia, to New South Wales and Philadelphia. Where the ‘wheels were harnessed to produce flour, the returns on the sale of this commodity were rapidly discerned. It covered the cost of the treadwheel’s installation, and ran at a dividend. Cheap prison labour also made economic sense, it kept the inmates busy, and there was a neverending supply, no matter how much agriculturalists might complain that it threatened their business21.

The treadwheel was, in all honesty, a product of the Industrial Revolution. And like many an innovation of that age, the human cost was conveniently ignored22.

In 1821, a male convict in Leicester died whilst on the treadwheel. Two years later, similar happened at the same institution. At another prison in 1824, a man knelt down on the ‘wheel, was caught in the mechanism, and crushed to death. Pregnant women forced to endure the ‘wheel miscarried. These were all findings noted in Thoughts on Prison Labour, and run in the Liverpool Mercury24.

The female inmates of Coldbath-Fields would regularly faint and fall off the treadwheel, or simply cry in agony. After being revived, they would be forced back on. It broke some of the guards too, not normally a class you’d associate with sympathy. One remarked that

…how often the finest of them, after having been a few weeks at work, are worn down and emaciated…

Qtd in Liverpool Mercury, June 4 1824, p3

Clearly the judgment ‘medically fit’ to work on the treadwheel covered a broad church of conditions, and it was the same for the men as for the women. The male convicts were put on the wheel even when they had ruptured hernias. As one Governor at Brixton observed,

They had several prisoners at their wheel who had ruptured, and when they had fitted them with trusses, they were usually worked with the rest.

Qtd in Liverpool Mercury, May 28 1824, p1

Others, held together with improvised bandages,

…complained most bitterly…

Qtd in Liverpool Mercury, May 28 1824, p1

…when the student asked them about the mental and physical distress caused by the labour.

Conflicting voices made themselves heard too. One noted how prisoners

…retire from it [the treadwheel] in the evening, in that fatigue of body and exhaustion of animal spirits, which renders them less inclined to mischief…that it is held in considerable dread by offenders is certain, and the fear of returning to it may operate favourably…

Bath Chronicle, July 31 1823, p2

The aforementioned Committee on Prison Discipline certainly approved:

…the primary feature in the character of ‘hard labour’ should be severity…a severity that shall make those who have violated justice, feel the penalties of law…the Tread-wheel is…a punishment of this description, and that no house of correction should be without it.

Bath Chronicle, February 10 1824, p2

In May 1824, a petition was presented to Parliament. It highlighted the unlawful introduction and barbaric nature of the treadwheel, but to no avail25.

With all this considered, then, the events at Bodmin Jail in May 1827 ought to come as no surprise. Complaining to sympathetic ears was one thing, but Bodmin witnessed a far more direct form of protest.

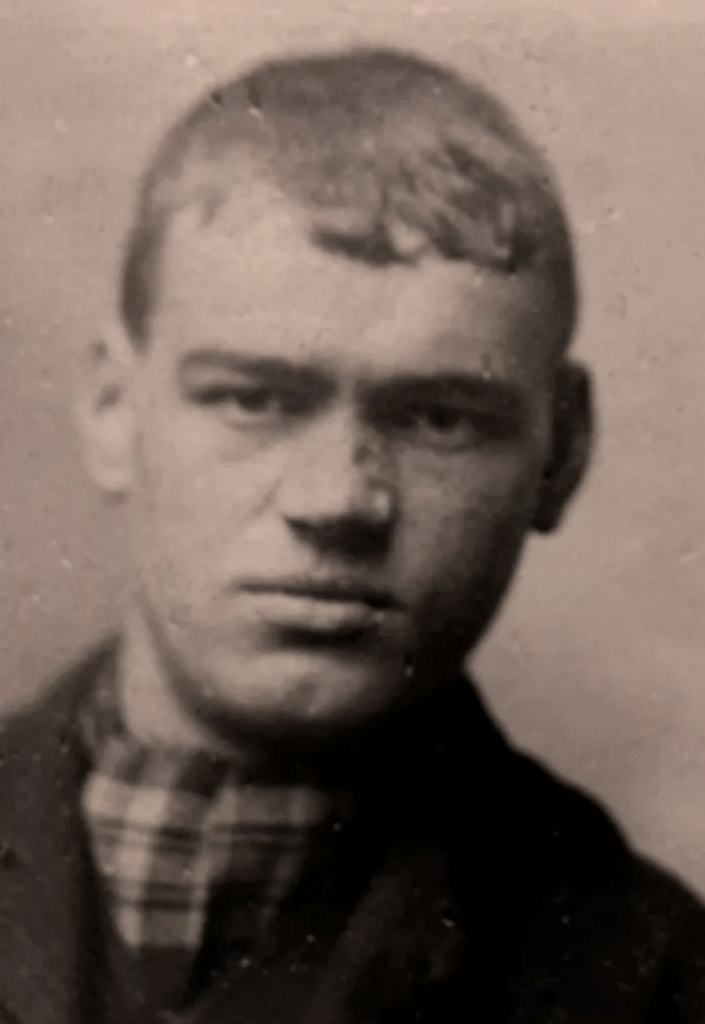

In the years before the invention of photography, portraiture captured the likenesses of the upper-class and nobility; a sketched ‘Wanted’ poster or a prison sentence offered a chance for the lower orders to have their appearance (briefly) recorded for posterity. To ensure a positive ID and track possible repeat offenders, jail registers often gave a brief description of new inmates, noting distinguishing marks (I’ve read of scars and missing thumbs), and behaviour.

It’s not an exact science; the researcher is relying heavily on the diligence of the prison registrar. But sometimes, you strike gold.

With James Sowden, we are unlucky. Either his prison record has yet to be transcribed by the amazing volunteers at Cornwall Online Parish Clerks, or it no longer exists, and we will never have any idea what Sowden looked like, or his age when he was sent down.

All we know for certain about James Sowden is this: he lived in Camborne, he was a miner, he got six months hard labour at Bodmin for assault, and…well, all in good time27.

But we can make educated guesses as to his biography. He may well have been the same James Sowden who married Catharine Richards in Camborne in 1832; neither could write. In the 1841 census, Sowden is listed as a copper miner. The couple resided at New Downs, near what was once Treswithian Downs, and had six children. He gave his age as 30, though ages in early census returns are rarely accurate, and 1841’s means of recording age was particularly eccentric. If this James Sowden is our James Sowden, he would have only been around 17 at the time of his visit to Bodmin Jail28.

In 1851, the family are living on College Street, Camborne. Here James Sowden told the census officer he was 34. He died in 1863, aged around 4829.

If this is the same James Sowden who was behind bars in 1827, then we might also say this of him: he was one hell of a fighter, he had courage beyond his years, he had a certain sense of the dramatic, and he was no champion of penal discipline.

Sowden was arrested on the streets of Camborne with two other miners, John and Richard Cock. John was 23, stood 5’8″, had grey eyes, a pale complexion and sandy hair. Richard was two years younger, an inch shorter, and had dark hair30.

The three men were doing time for assaulting both of Camborne’s (voluntary, unpaid) parish officers, Henry Eva and William Terrell, “in the execution of their duty”31. Sowden and the Cocks were probably drunk and violent when the officers intervened, and said officers were made to bitterly regret taking this course of action. Eva and Terrell may very well have been the first law enforcement officers to come second to Camborne’s miners, but they weren’t the last32.

At the Truro Easter Sessions, all three were given six months at Bodmin. On the treadwheel.

Several other likely lads were handed similar sentences at the same hearing. Three miners from Kea (between Carnon Downs and Truro) got nine months on the ‘wheel for beating up their parish constable. They were Robert Northey (21), James Francis, also 21 and who stood an impressive 6’1″, and John Bastian (22)34.

Joining them from Illogan were another trio of miners, on a 15-month stretch for riot and assault: Stephen Rickard (21), William Martyn (20) and Richard Branch (21). Like their fellow convicts from Camborne and Kea, they were to have the pleasures of the treadwheel too35.

I dwell on these eight men who were sentenced with Sowden because, although it’s only his name that’s connected with the events at Bodmin Jail on May 14, it’s likely these men acted with him. In the case of Rickard, Martyn and Branch, highly likely. The records describe their behaviour as being

…not very orderly…very disorderly…very disorderly…36

Who knows what Sowden’s entry read.

So, they were sentenced on April 24, and entered Bodmin Jail on Thursday April 26. Less than three weeks later, on Monday May 14, enough was enough.

Miners are conditioned to hard work, but they also expect a material return for their labours. Bodmin’s treadwheel would offer them no such recompense, plus this early incarnation of the device at the prison was especially fiendish. Though as noted earlier it only sat ten, it was

…regulated by friction only, a very uncertain method. The wheel is made of wood, and from its rough manufacture revolves very unsteadily!

Thoughts on Prison Labour, by a Student of the Inner Temple, London, 1824, p94. Retrieved from Google Books

(By 1883, Bodmin’s wheel had a capacity of thirty-two inmates, and would grind corn38.)

If one convict pushed too hard, he would throw his fellow sufferers off their rhythm, causing them to overbalance and, like as not, injure themselves. Treading on rough, unfinished timber all day must have made the experience all the more hellish.

We are not told how many prisoners were to be on the ‘wheel that day, but obviously there cannot have been more than ten. They lined up in the yard after another night in solitary and a thin breakfast chewed in silence, and faced up to another day of agony39. If they had a plan, it may have been no more than a hasty whisper: I’m not going on; who’s with me?

Suddenly, they refused to step on the treadwheel, or rather

…manifested signs of insubordination…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 19 1827, p2

We can imagine Sowden, identified for all time as the ringleader, standing forward of the rest, arms folded, staring down the guards.

The guards patently lacked the numerical superiority to take on a bunch of defiant miners. They also lacked the stomach; after all, these were men who made a pastime out of battering officers of the law. They panicked, and when subordinates panic, they look to their superiors, which is exactly what happened.

Two magistrates were on hand that day: Joseph Pomeroy, and Nicholas Kendall (1800-1878). Kendall wasn’t the kind of man to panic; in fact he made it his business to quell riots quickly and bloodlessly. He was to do it again at St Austell in 184740.

At the magistrates’ appearance, the miners armed themselves, tearing up the treadwheel’s railings. They then assumed battle formation.

Kendall showed the quick decision-making that was to be crucial in 1847. The unrest needed to be stamped out rapidly, before other inmates got similar ideas and the situation got out of hand. Kendall needed a show of strength. Fast.

The 32nd Regiment of Foot (later, the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry) was in Limerick, but the militia of the Royal Cornwall Rangers were conveniently nearby in the town. It’s unknown how many of this irregular fighting force Kendall was able to rustle up, but he did it in short order – in all, the events of that day took several hours at most42. They lined up in the prison’s outer courtyard. Kendall informed the rebellious inmates of their presence. Last chance.

At this point, the hastily-assembled militiamen would have known they were in for a fight. Loud cheering came at them over the prison wall, and the cry went out,

…death or victory…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 19 1827, p2

Kendall, thus being challenged to do his worst, obliged, and ordered the soldiers in.

Once they got past the gate, the prisoners, with no regard for personal safety, fell on the riflemen, thrashed at them with their improvised weapons, and struggled to gain possession of the muskets themselves.

It’s at this point that the riot could have turned into a massacre. If one or more of Sowden and his desperate cohorts had got hold of a rifle, or an excitable Ranger had opened fire, who knows what carnage would have ensued.

We may detect the hand of Kendall here. If a shot was fired inside that prison, he was in serious trouble. Discretion and forbearance was required, and would have been stressed on the soldiers. It was a lesson he took with him to St Austell.

Rifle-butts and elbow-grease did the job. When it was over, several convicts lay prone on the ground, and the rest had retreated. Five of the worst were dragged off to the detention cells.

Except James Sowden:

…being the ringleader, [he] was again ordered by the Magistrates to ascend the wheel.

Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 19 1827, p2

All eyes were on Sowden. He probably drew himself up, stuck his chin out at Kendall, and

…positively refused…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 19 1827, p2

This was the last straw for Kendall. An example had to be made. Sowden had just volunteered himself.

He was strapped down and whipped, right there in the yard.

Whatever fight the prisoners had left was crushed by this horrifying sight. Sowden was probably whipped unconscious, and left bleeding in his ropes for a while. The men he had led to rebel, possibly including his mates from Camborne, the Cock boys, knew it was over. Back to the ‘wheel they went.

For James Sowden and his fellow prisoners, there was no death or victory, only brief defiance followed by pain and humiliation.

The use of treadwheels in Britain’s prisons was only abolished in 1902. That same year, we discover that Bodmin’s modern, 32-man monster ‘wheel had been sold on44.

Sowden’s uprising changed, or achieved, nothing. Nor, you could argue, did the object of his riotous wrath. One historian has commented that

There was no evidence that the treadmill had any impact on crime rates, or the size of the prison population.

Professor Rosalind Crone, Open University45

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Quotation from: U. R. Q. Henriques, “The Rise and Decline of the Separate System of Prison Discipline”, Past and Present, Vol. 54 (1972), p61-93. Henriques notes that Smith was actually pushing for prison reform. The ‘Treadmill Song’, also known as the ‘Gaol Song’, was sung to a folklorist by Dorset workhouse inmates in 1906; its origin is probably much earlier. See: https://mainlynorfolk.info/lloyd/songs/gaolsong.html

- Image from: http://www.artuk.org/artworks/a-rakes-progress-7-the-rake-in-prison-123979

- See: U. R. Q. Henriques, “The Rise and Decline of the Separate System of Prison Discipline”, Past and Present, Vol. 54 (1972), p61-93. For more on Howard, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Howard_(prison_reformer). For a brief overview of the Act, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penitentiary_Act_1779

- See: Douglas Hay, “Property, Authority, and the Criminal Law”, in Albion’s Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England, 2nd ed., Verso, 2011, p17-64. For a brief overview of ‘The Bloody Code’, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bloody_Code. For more on the history of transportation, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penal_transportation

- From: U. R. Q. Henriques, “The Rise and Decline of the Separate System of Prison Discipline”, Past and Present, Vol. 54 (1972), p61-93. For more on Elizabeth Fry, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elizabeth_Fry

- Image from: https://londonist.com/london/jeremy-bentham-ucl-body-auto-icon-where. Bentham’s eccentric afterlife is as well-known as his work. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeremy_Bentham, https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/transcribe-bentham/jeremy-bentham/, https://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/museums/2013/07/12/bentham-present-but-not-voting/

- For more on Call, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Call. How Bodmin Jail was built can be read here: https://www.theprison.org.uk/BodminCGB/

- Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Call. The photographer Jackie Freeman asserts that the building behind in Call is Bodmin Jail: https://www.jackiefreemanphotography.com/bodmin_jail.htm

- Quotation from: https://www.theprison.org.uk/BodminCGB/

- John Howard measured the cell dimensions during his visit of 1784: https://www.theprison.org.uk/BodminCGB/

- From: https://www.theprison.org.uk/BodminCGB/. For more on Neild, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Neild

- Image from: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/vem7sjza/images?id=ejbzn8sq

- Information from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Britannica-on-the-treadmill-1998450#ref1205851. Of course, being judged medically unfit to tread the wheel didn’t mean you were excused hard labour. Instead you were made to sit and turn ‘The Crank’, a steel box filled with sand with a handle on side. See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/04G2X6rXSsiAvbotujleew

- Image taken from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Britannica-on-the-treadmill-1998450#ref1205851

- Stills from: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/the-legacy-the-victorian-prison-treadmill

- Figures from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Britannica-on-the-treadmill-1998450#ref1205851 and https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/the-legacy-the-victorian-prison-treadmill. The treadwheel uses are noted in: Bristol Mercury, February 24 1823, p4, and Salisbury and Winchester Journal, December 29 1823, p2.

- Exeter Flying Post, October 24 1822, p4, and https://www.theprison.org.uk/BodminCGB/

- See: https://www.jackiefreemanphotography.com/bodmin_jail.htm#treadwheel

- For more on the Act, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Slave_Trade_Act_1824

- Liverpool Mercury, May 21 1824, p7.

- Bath Chronicle, July 3 1823, p4.

- For examples, see: E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class, Penguin, 1991, p207-232.

- Image from: https://cdn.nationalarchives.gov.uk/documents/education/victorian_prison.pdf

- May 21 1824, p7.

- See: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1824-05-05/debates/6f72505c-a667-42fa-8688-cf14cb80f052/Tread-Mill%E2%80%94PetitionOfSirJCHippisleyAndCAgainstTheUseOf

- Image from: https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/fascinating-1800s-mugshots-reveal-greater-24842983

- Easter Sessions, Truro, April 24 1827. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/11/254. Another James Sowden was given six months hard labour at the Bodmin sessions of 1829; but as this Sowden resided at Lostwithiel, it’s unlikely to be the same man. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS1/11/500.

- For the 1841 census, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1841_United_Kingdom_census. The marriage record is available here: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=marriages&id=1858413

- The burial record is available here: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=burials&id=5261897

- See the Cocks’ prison records here: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=institution_inmates&id=149011, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=institution_inmates&id=149010

- Easter Sessions, Truro, April 24 1827. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/11/254. Of course, there was no police force; Cornwall Constabulary was only formed in 1857.

- In 1873, Camborne bore witness to the largest anti-police riot in Cornish history: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/09/30/the-camborne-riots-of-1873-part-one/

- Image from: One & All: A History of Policing in Cornwall: The Cornwall Constabulary 1857-1967, by Ken Searle, Halsgrove, 2005, p18.

- Easter Sessions, Truro, April 24 1827. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/11/254. See the descriptions of the three Kea convicts here: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=institution_inmates&id=149015, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=institution_inmates&id=149017, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=institution_inmates&id=149016

35. They had been inside since March, but were only sentenced on April 24. See: Easter Sessions, Truro, April 24 1827. Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/11/254, and https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=institution_inmates&id=148969, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=institution_inmates&id=148971, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=institution_inmates&id=148970

36. See the links in note 35.

37. Image from: https://blog.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/2021/04/15/exploring-life-behind-prison-bars/

38. Cornish Telegraph, December 6 1883, p8.

39. Only one Cornish newspaper covered the riot, and that was the royalist, conservative Royal Cornwall Gazette of May 19 1827, p5.

41. Image from: https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/nicholas-kendall-b-1800-14110. For more on Kendall, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nicholas_Kendall_(Conservative_politician)

42. The Rangers had formed in 1760. See: https://www.lightinfantry.org.uk/regiments/dcli/duke_timeline.htm

43. Image from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/flogging

44. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Penal_treadmill, and Cornish Guardian, August 1 1902, p3.

45. From the OU film available here: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/history/the-legacy-the-victorian-prison-treadmill