Reading time: 30 minutes

…there is something worth knowing in the Cornish mode of wrestling… ~ R. M. Ballantyne, Deep Down, A Tale of the Cornish Mines, 1880, p157

…many dispute when exactly was the Golden Age of Cornish wrestling…but whenever it was, it isn’t now… ~ BBC’s Tonight programme, 19651

…you take the glory or you take the stick – there’s only one winner! ~ Gerry Cawley

Wrasslin’?

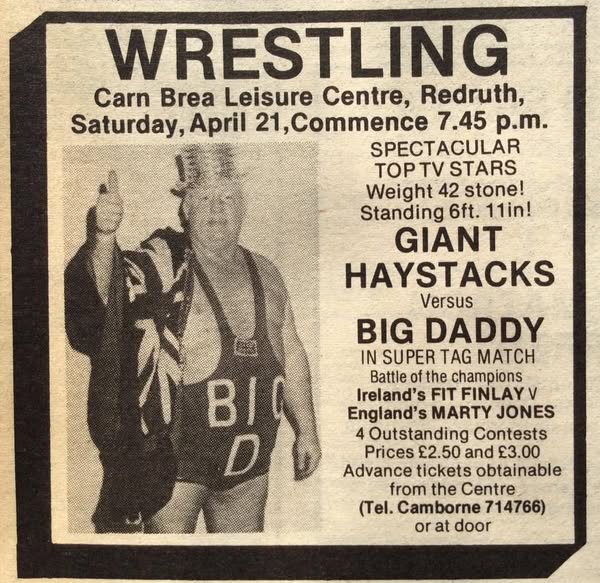

I remember my gran getting all keyed up to go and watch the wrestling at Carn Brea Leisure Centre in the early 1980s. My dad, who was playing the role of chaperone, told me she positioned herself near the ring with her cronies (each resembling Mrs Wilberforce in The Ladykillers), and all of them proceeded to wave their walking sticks and shout encouragement and oaths with equal vehemence at the gladiators before them. Father said he’d never heard gran use language like that before or since. Clearly, she’d had a grand old time.

I’d like to report it was Cornish wrestling, or wrasslin’, that was getting these dear old ladies so hot under the collar, but no. The immensely popular ITV professional wrestling programme of the 1980s had gone on the road with two of its biggest draws:

This is the point: I strongly suspect that my gran, who was born in 1910, never watched a Cornish wrestling bout. For even in Cornwall itself, it’s fair to say Cornish wrestling is a minority sport. It might even be an endangered species2.

Like hurling, Cornish wrestling only exists now in a few rural enclaves. There’s only two clubs, at St Columb and Sithney, though St Mawgan organises an annual tournament. In 2018 there were only 39 registered wrestlers: seniors, juniors, men and women. Its practitioners are, on the whole, reduced to giving demonstrations at local fetes and fairs which regularly feature other traditional countryside pastimes and ways of life under threat of disappearing altogether. At Camborne’s 2025 Trevithick Day celebrations, wrestlers featured alongside morris dancers and a parade of bal maidens3.

It wasn’t always like this. Cornish wrestling has a long, long history, its origins going back millenia. Its heyday was in the first half of the 19th century, when every town and village would have its tournament and its champion, and could draw crowds of several thousands for the big contests. Great were the prizes and reputations at stake.

The great Cornwall-Devon grudge match of 1826, between St Columb’s James Polkinghorne and Abraham Cann at Tamar Green near Devonport drew a crowd of around 18,000. Gentry had box seats in temporary galleries and stands; the riff-raff roughed it on surrounding hillsides. Bands pumped out the tunes and local victuallers made a killing. The winner could expect a £200 jackpot – in 2025, that’s nearly £17K.

For all the hype, in newsprint and elsewhere, the battle ended after three hours in an acrimonious draw, with both sides claiming victory. Beneath all the wrangling over who won lies the fundamental reason why Cornish wrestling remained forever Cornish, and retracted in popularity over time rather than expanding or consolidating.

For not only are the rules and methods governing the Cornish form of wrestling markedly different from its nearest geographical neighbour, but Cornish wrestling (for that is what concerns us here) also differs from other forms of wrestling in the British Isles, for example the Cumberland-Westmorland style. Its use of a canvas jacket also differentiates it from the two styles recognised at the Olympics, Greco-Roman and freestyle. The only form of wrestling compatible with the Cornish style is, perhaps unsurprisingly, the gouren variety found in Brittany. Of course, Cornish wrestling is also nothing like its professional counterpart.

This fundamentally localised aspect of the sport, combined with the advent of modern pastimes and several other factors, has meant that Cornish wrestling now finds itself embattled and beleaguered.

All this isn’t to say, however, that Cornish wrestling is no longer relevant, or worth bothering with. Cornish wrestling ought to be considered on its own terms. If we take it at face value, we discover that, much like any other sport, Cornish wrestling has its infrastructure, its fans, its advocates, its historians, its purists and its innovators. It has its code, its culture, its traditions, its terminology and its notion of fair play. (Indeed, the oath every wrestler has to swear contains the words gwary whek yu gwary tek – good play is fair play.) It has its anecdotes, its stories, its rivalries, its controversies, its winners and losers, champions and gallant also-rans. It has its villains.

And it has its heroes.

Champion wrassler

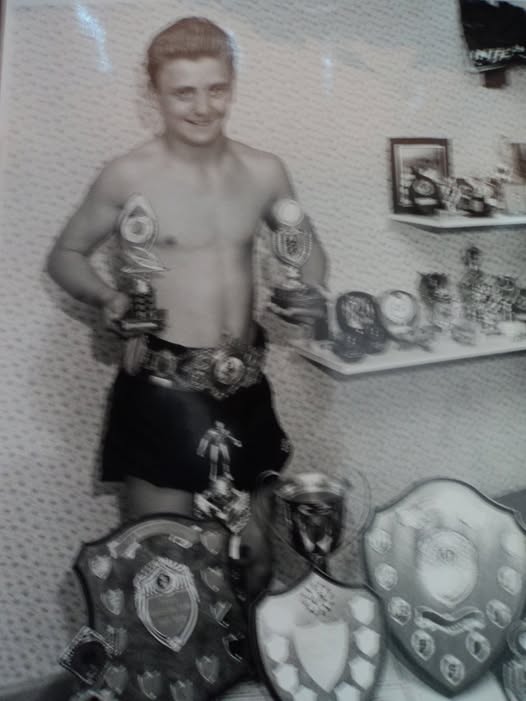

Cornish wrestling’s biggest hero is Gerry Cawley. A member of the construction industry from St Mawgan, Gerry (born in 1961) is Cornish wrestling’s equivalent of cycling’s Eddy Merckx6. Like the man from Belgium they called Le Cannibale, Gerry Cawley has won everything worth winning in his chosen sport. Since the 1980s, the name Cawley has become synonymous with Cornish wrestling.

St Mawgan’s always had its annual wrestling, like most every village used to have, but they’ve all disappeared one by one.

We were four boys, I was the youngest, and this year like all the others we went down to watch the wrestling in the village. And the older ones, they all put their name down to give it a go and enter the novice competition. But I was only 11 or 12 and I didn’t, but mischievous as brothers are, I knew nothing ‘bout it ‘till my name was announced over the microphone, they’d entered me while we were at the table!

What you’d call a hellfire baptism! I ‘ad five minutes’ behind the tent, bit of tuition by one of the other boys in the village that’d done a bit before and he showed me a move or two…unfortunately, when the names were pulled out the hat, I was in with him!

I managed to come third in my first ever competition, and I think that was just basically through a natural flair, a natural ability based around speed. The rest of the brothers followed it throughout the rest of the summer season, that was it, we were basically all smitten, and carried on from there!

If a youngster shows enthusiasm or aptitude for a sport, nowadays they are pointed in the direction of the nearest club. For a keen wrestler in 1970s St Mawgan, that was impossible:

There was none! I got tuition locally in the village by an old gentleman, he’d wrestled in the 20s and the 30s, and he showed me the old ways. As a youth I’d done very well very fast, and what that leads to is all the old wrestlers, the sticklers [referees], when you’re good, they take to you and they offload a few of their special moves and tips to you.

They’re always right there with advice, ‘cause they’ve enjoyed watching you win, and if you did do a little bit of something wrong, they’ll point it out to you and give you help. There was no clubs.

The time-honoured oral traditions of Cornish wrestling carried the sport for centuries, but Gerry is more than aware of the limitations of this approach in the modern age:

Cornish wrestling goes back through the mists of time, basically the martial art of the Ancient Britons. In Cornwall, for all those millennia, there wasn’t a lot of sports. You had hurling, wrestling was the more popular, but it’s handed down there, father to son, brother to brother, in the workplace, in the schoolyard…

…it was the birthright of a young Cornishman. The boys couldn’t wait to join the ranks and learn to wrestle and give it a go. Wrestlers were that numerous, you only had to look at tournaments in the 18th and 19th centuries, you’ve got hundreds of wrestlers turning up, and thousands of spectators! In that environment, there was no need [for clubs] , there was never an infrastructure in Cornish wrestling. The first association wasn’t formed until 19237, but people trained in the different areas and you would have your large families who would train amongst themselves, and that’s the way it carried on.

When it comes to the First World War, I think that was the first big downfall [for Cornish wrestling]. In the 1920s that was really the last big time. You lost so many fathers and grandfathers, people who could teach and hand it on. And of course so many Cornishmen for a long time were leaving Cornwall, working and wrestling right around the globe, but not many of them came back. So you’re losing all that potential for training youngsters between the wars.

War, collapse of industry, emigration…it’s no coincidence that the Cornish Wrestling Association (CWA) was founded at around the same time as the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, whose mission statement was

…the preservation of everything bearing on the history and antiquities of Cornwall…

Cornish Post and Mining News, January 10 1925, p7

…at just the time when Cornwall was changing forever. You have to say the Federation has succeeded admirably. But the CWA was riven with internal strife over just what ‘traditional’ Cornish wrestling was, with several splinter organisations forming. All this served to hamper the sport’s development.

Women’s competitions were only permitted in 1994, and the CWA finally affiliated with the British Wrestling Association in 2004. A definitive Cornish wrestling rule book became available in 20118.

As Gerry readily admits, for

…the two clubs, it’s too little, too late. You could have done with that a long time ago…We suffered…

By the time we come to the 1960s, there was really a problem, but that was helped out by Truro Cathedral School, had it introduced to the curriculum. Half of all the [Cornish] wrestlers came from the school! They kept it alive, basically.

Cornish wrestling’s great hope

Fortunately for Gerry, when he took up the sport in the 1970s it was enjoying something of a revival. Cornish wrestling might not be an Olympic nor, despite lobbying in 2019, a Commonwealth sport, but its exponents can take their game on the road and compete against their Breton counterparts. Wrestlers from Brittany first visited Cornwall in 1929 and, despite occasional lulls (especially during World War Two), exchange trips have been taking place ever since. Nowadays the event has evolved into an inter-Celtic wrestling tournament associated with the annual AberFest celebrations10.

Starting in the U16s at age 14, Gerry won the Cornish title three years running12. He was already known for his speed, and taking on bigger, older lads never worried him. After all, he was the youngest of four wrestling brothers:

It is possible for the smaller man to throw the larger man. All things being equal, you need the skill and you need the speed. But there’s certain throws, once you get into a position, they can’t get out of it.

It has been known in open competition for the lightweight champion to throw the heavyweight champion! Once you’ve blocked the outside ankle with your heel, you’ve stepped across them to stabilise yourself, they [your opponent] needs to step sideways, and they can’t. You’ve locked your leg against them.

Moving up to the U18s, in the Final he came up against the reigning champion:

I took him out clean on the back, and once those sticks go in the air from the sticklers, it’s all over! No good arguing the toss with the stickler, they don’t wear that! Like one said one day, ‘If you wanna find out who won, boy, look in next week’s Cornish Guardian!’

He’d already been to Brittany aged 16. Traditionally, Cornish wrestlers don’t do well against Breton opponents. When Gerry started, the only Cornishman to make his mark was Francis Gregory, and they’d only won as a team in 1947. It’s easy to see why:

They’ve had academies for a long time. Same as they have in Cumberland and Westmorland. If you’ve been to Brittany yourself you’ll see how good they are on their heritage, their culture and the preservation of it all…and they’ve always had clubs, which is another thing. Each reasonable sized village has its own club. They start them young and they nurture them, which again was in advance of us doing it. The sheer number of wrestlers in Brittany and the interest always makes the standard higher, really.

Allied to this, Gerry is of the opinion that Breton wrestling is a more ‘pure’ version of Cornish wrestling, due to the cross-channel migration of the Cornish to Brittany in sub-Roman Britain14. Be that as it may, he took the U16s and U18s inter-Celtic titles on his first trip:

That’s the only time someone has held both titles at the same time since 1936…I’d done everything by the time I was still a teenager. When I was 19 I went over there [to Brittany] and won the middleweight, so I’d had 12 titles in championships by the time I was 19!

Gerry has been to Brittany five times, and every time returned home victorious. One year, he told me, the Cornish team lost 10-1. He was the only man to win his bout. Lurking in the background, though, would be the issues of lack of funding and recognition. In 1979, the CWA requested financial aid from Carrick Council to enable them to host that year’s inter-Celtic tournament at St Stephen-in-Brannel:

…who had decided not to offer any financial help because they had already exhausted their allocation of grant money.

West Briton, September 6 1979, p5

Nevertheless, the cash was scraped together and the 50th anniversary of a Breton wrestling team coming to Cornwall went ahead. For the first time since 1947, the Cornish team won, a victory made all the sweeter by the fact that St Stephen has hosted wrestling tournaments since 129115. Naturally, Gerry won his middleweight bout. But he was thinking bigger.

Cornwall’s heavyweight

Just because Cornish wrestling is an amateur, self-funded minority sport, doesn’t mean that its practitioners lack dedication or ambition. Indeed, you might argue they’re all the more committed for these very reasons.

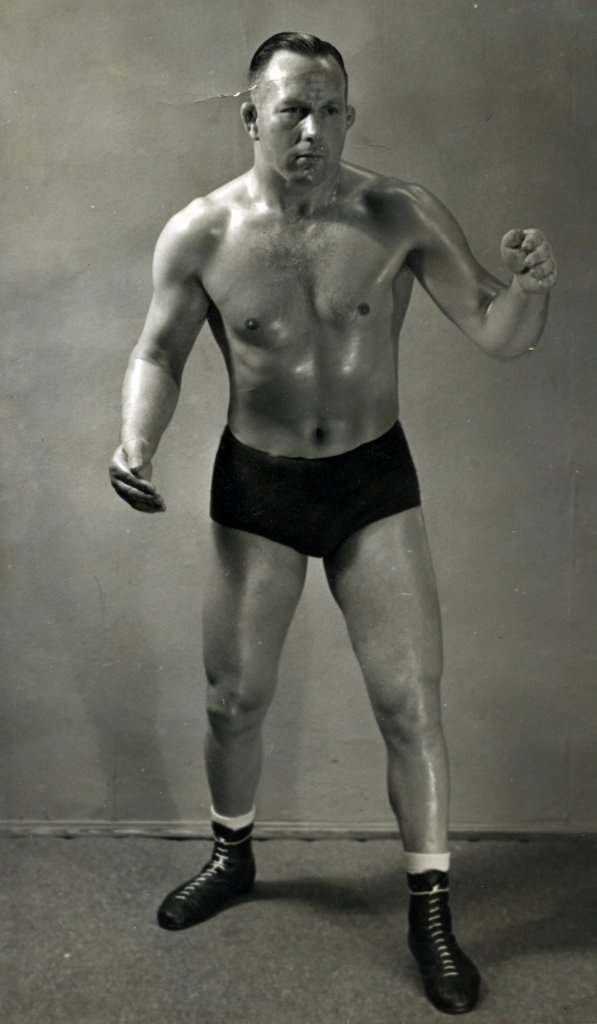

There’s few more committed than Gerry Cawley. At 5′ 7″, he was always a natural middleweight at 11st 11lbs. It wasn’t enough:

I could’ve done that for ever and a day, but my ambition was to try and win everything, the light-heavyweight and the heavyweight. That’s why I started training, and eating, and trying to build up, to compete on a better footing with larger contestants.

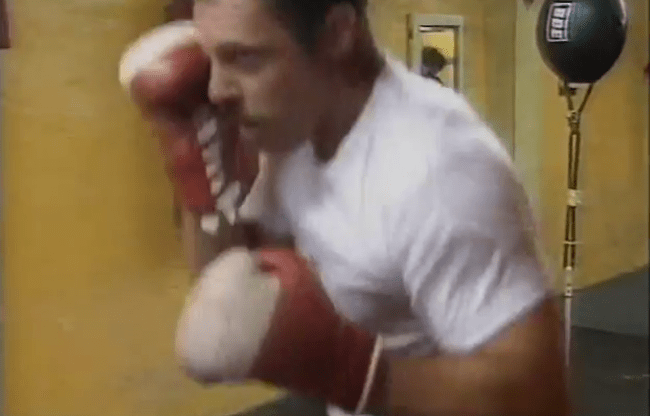

He found bodybuilding and, later, boxing:

I never went near a boxing club until later in life when my eldest was ten, I took him to learn to box. Rather than just drop him off, I used to stay there and do it, more a recreational boxer!

I was looking for something else…just to see what you can do. You challenge yourself, because it’s not a team sport. It’s man-on-man, and it’s all down to you. So you take the glory or you take the stick – there’s only one winner! You wanna be the best, but you’re testing yourself.

With a full-time, physical job and a young family, Gerry trained whenever he found the time, or the mood took him:

I didn’t do a lot of training! You’d be wrestling all through the summer every other weekend, then you’d do demonstrations, so you were always basically doing it. Practising was just down the park, on the grass with your mates and you would try things and have a good time.

As far as bulking up, I would work hard with the weights, but again with no real club. You weren’t tied to set training, I ran when I wanted and swam when I wanted. I didn’t have anything hard and fast, but then I was spoilt really because I do think I was natural for the sport. I could always beat me brothers, and they were all older than me. I’ve been described as a coiled spring!

Just when they [my opponent] went to do something, I’ve countered on it, and it’s all over. It’s all speed. As I got older, I only added experience to it and got stronger and heavier. But I was never going to make a national heavyweight…You’ve got to rely a lot of the time on those natural abilities.

Gerry said he also wanted more ‘timber’ on him, as he put it, to counter being knocked about as a youngster in the ring with older men. When he began there was no real youth categories in the sport, he told me, so if you wanted to practice outside of tournaments, you took what you got.

By 1983, he was Cornish heavyweight champion. But a bigger challenge awaited him.

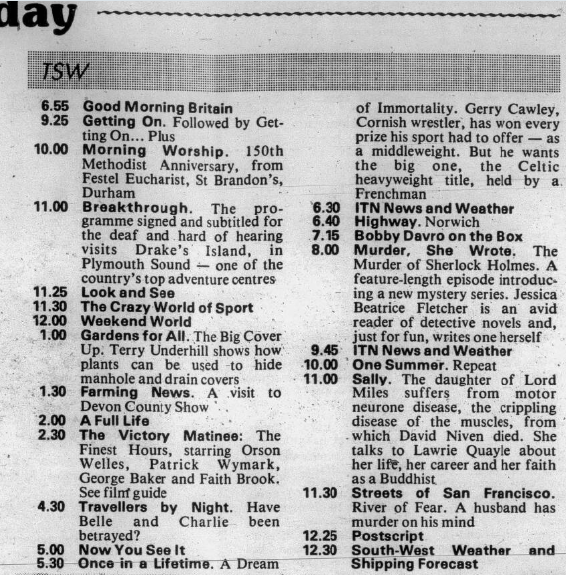

A Cornish wrestler on TV

In 1985, Gerry became a star of the small screen when he appeared on the ITV documentary Once in a Lifetime. Being Cornwall‘s wrestling champion was all well and good, but could he unite the Cornish and Breton belts as inter-Celtic champion? Any heavyweight unification bout is newsworthy, and Yorkshire Television’s Barry Cockroft, who resided in Cornwall, got wind of the match-up17.

Gerry was to meet Jean-Yves Péran, gouren‘s alpha male, in Brittany. Today, Gerry is phlegmatic:

I’d started building up then, just out of my teens, they came to you, and you weren’t going to turn them down! Personally I wasn’t ready for it, I didn’t win, but I got a shilling out of it, wonderful experience.

Jean-Yves Péran, he’s a typical Breton wrestler in that he’s been there since he was a toddler, trained in the academies…he’s a very good technician, taller than me, but he was so much more advanced in his technique and training.

I wasn’t mature at the time. I would have liked to have done it a few years later. But it was a wonderful experience!

Mature or not, Gerry wasn’t going to turn down the chance to promote his sport nationally, nor the significant payday on offer:

I took the time off work, we didn’t do much filming, we shot the opening sequences down St Mawgan because the trees and the church make a beautiful amphitheatre. But then we all had to pack up and go over to Brittany. It all took a week. But they were paying for it – that’s where I got me £400 from! The family went, my mum had a thoroughly good time.

It was a fairly small outfit, one main cameraman, producer, director, assistant and sound man. It wasn’t a big affair.

The £400 Gerry received was his biggest career earnings. From around 40 years in the sport, he reckons to have made £1,000 from wrestling. But of course, like all amateur sportspeople, you do it because you love it.

It wasn’t always so. Even in the 1960s, Gerry said, you could wrestle all summer and earn decent money:

When I started in the 70s, you used to win a few bob, in the novices there might be £5 for first prize. One of the measurements for not being a novice anymore was when you’d won £7! So then you had to compete in the open tournaments.

In the 1980s the money had run out, apart from the heavyweight [championship], one day a year for the belt, that would be a £10 prize. The wrestling community was getting smaller and they were all doing it for the sake of the sport. But when it comes to the championships, we’ve got five belts, and a big silver two gallon cup for the light-heavyweights (which holds 16 pints!), which was given by Walter Hicks of St Austell Brewery.

You would enter them for nothing: to become champion of Cornwall, for a Cornishman, that’s what it’s about. Pride for the belt. Down at St Mawgan we still give some good prize money; if you won the open tournament you’d probably win £50, but we’re the only remaining committee left! There’d be 30 or more in the 1920s, under the auspices of the [Cornish Wrestling] Association, but it’s not like that now.

The CWA has to organise and run most of its tournaments itself. Unfortunately they’re so often tacked on as a bit of a sideshow to a rally, a fete or a fair. Ours at St Mawgan stands alone nowadays, apart from Castle-an-Dinas the last couple of years. Nothing else stands alone as wrestling for wrestling’s sake.

But for me it’s always been the pride of it, anyway.

Cornwall’s tournament king

Gerry’s stellar wrestling career continued. He was Cornish heavyweight champion again in 1984, 1991, 2002 and 2007. Besides the bouts and the tournaments, he has given countless demonstrations all over Cornwall. He still prepares the ground for the annual St Mawgan tournament to this day:

They [events organisers] always come looking for you. There’s a lot of regular regattas and fairs and fetes and things in Cornwall. I think it’s some years ago now they all learnt, really, that if you want us, you’ve got to get in contact with the secretary the year before. There’s always the tournaments, which aren’t so numerous as they used to be, then the fixture list will be compiled for the year around who wants a demonstration.

But you’ve got your standards in your big towns, your standard tournament is more or less the same time because you’ve got to allocate your championships for the year, and you want a good venue with the best possible attendance.

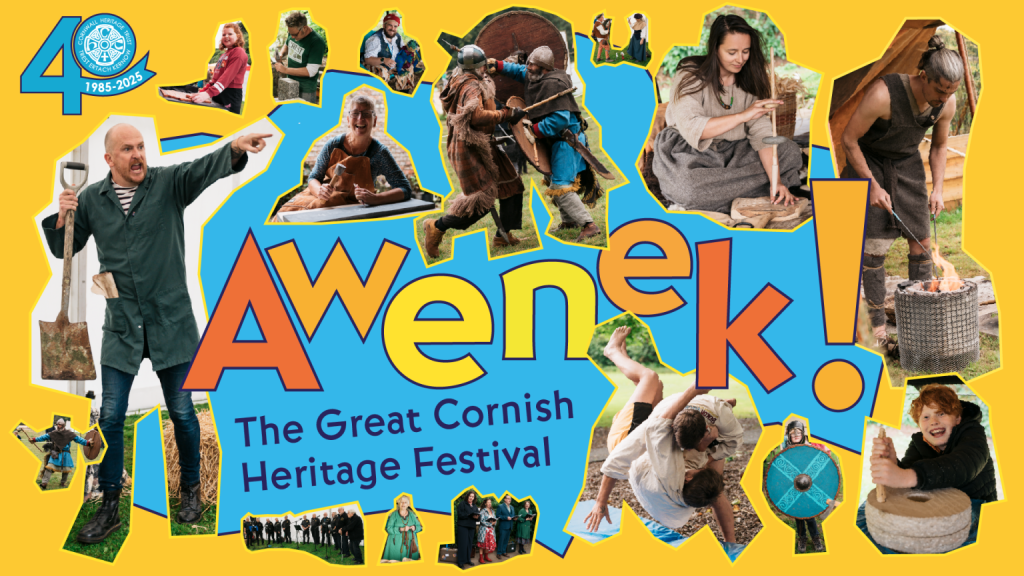

Naturally, Gerry and his fellow wrestlers are cultivated by various pro-Cornish groups21:

Because it’s always been there, it’s integral. If they have a country fair people would want you for a demonstration, because you’re Cornish, because you’re traditional. It’s nice to work in harmony with other Cornish people. We get assistance from the Cornwall Heritage Trust, so we all help each other.

Another external challenge hit Cornish wrestling in the late 1970s and early 1980s: judo.

The last round?

Otani was the first judo wrestler that came over to this country and toured in the music halls, taking on all-comers. The challenge was for them to stay 15 minutes with him.

They came down to Plymouth, and the secretary of the Cornish Wrestling Association took some wrestlers up. Francis Gregory threw him several good turns, but he was only 16! And our heavyweight champion, Fred Richards, he became the first man to hold and contain Otani and won the forfeit that they had never had to pay out before.

From these music-hall, exhibition origins, judo has grown. A quick online search shows nine clubs in Cornwall alone, and additionally 20 karate or martial arts clubs.

…but the youth of today, the vast choice is for martial arts now, they’re all usually indoors on soft mats and other good aspects to it. To get youngsters to go out and smite each other on the floor and on the grass, it’s not easy nowadays. To them, it’s looking backwards to old traditional stuff, but there’s so much new stuff, everyone wants something more exciting and more attractive in other ways.

I mean, look at the success of judo around the world, with the structure, the way its built and what they offer. It [judo] was there, it was in schools, you had a job to get Cornish wrestling in schools, but everybody took to judo because it got established internationally, governing bodies, everything was done right.

Hollywood played its part here too. Who didn’t fancy a crack at martial arts in the 1980s after watching The Karate Kid? I know I did. Controversy arose, though, when judo exponents took up Cornish wrestling themselves, many of whom met with easy success. There was a certain sense among the Cornish wrestling establishment that, though they respected the judokas‘ skill, they were bringing too much of their own sport into the ring:

…sometimes they don’t stray very far away from the judo. When you get two of them in the ring, you can see them reverting back! Yeah…I would prefer to see good Cornishmen, as long as they were traditional Cornishmen, I would like them to learn and take on all the ins and outs of the sport.

Because what’s important is to pass it [wrestling] on. You might gain a competitor, but you haven’t gained a man for the sport if he isn’t passing on the correct, pure way. You want this sport to continue in the manner it’s always been played.

I’ve nothing against judo players, and they’ve produced some very good champions, Keith Sandercock in particular, lightweight. Fantastic. We’ve had many a good tussle!

Critical mass was reached in 2000. Glyn Jones, a formidable black belt judoka originally from Devon, had won the heavyweight title in the previous two years. Obviously some felt it was time the title was returned to a Cornishman, and a pure wrestler at that. Gerry was 38 and had been wrestling for over 20 years, but he had retired. Gamely, he agreed to step back into the ring one last time and restore Cornish honour.

If all this sounds like a hackneyed movie script, that’s exactly how it was marketed. The BBC series Close Up made a documentary of the match’s build-up entitled The Last Round?, the preview of which states

…what is at stake is more than just personal pride – some say it is a fight for the very heart and soul of the sport itself…In the programme Gerry hits the comeback trail determined to win back his crown for the traditionalists24.

Gerry, in between pounding the heavy bag, says in the film that

I would like to take the belt, there’s no two ways about that, just for the sake of the sport, and to make sure there was a Cornish wrassler as the champion25.

Gerry lost. Jones took the title again in 2001, and then turned his back on the sport. Nowadays Gerry is sanguine about the whole affair:

I’d retired and was long past me best. But likesay they [the CWA] had nobody to match him. My youngest wasn’t old enough, he was coming up through the ranks…but, again, they come to me and if you wanna shine a camera, I’ll dust off me shorts!

Don’t get me wrong, judo is a good sport and your form of wrestling isn’t the only one in the world. There’s about 83 different styles of wrestling around the world. Any country has usually got their own blend. We’re all in the same game. And we don’t mind interaction, we have a lot of people giving it a go now, because the Mixed Martial Arts are popular now, and these people, right away you know they’re open to trying different sports. And they’re usually adept at picking it up and being able to stay within the rules.

As regards Glyn Jones, Gerry told me he bore no personal animosity toward him; indeed, he barely knew him:

I don’t know if he took it to heart because he never wrestled no more after that.

Jones certainly did take his casting as the villain to heart, putting his thoughts in print via The West Briton:

In my opinion all the people…who run wrestling have their heads stuck in the last century and refuse to move with the times. If you are not Cornish or in a real Cornish job [he worked for McDonald’s] then you are a real pariah. They do not actively teach the sport and do nothing to publicise it…

Qtd in Mike Tripp, Cornish Wrestling: A History, Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 2023, p134

That was over 20 years ago, and Cornish wrestling has moved with the times. Besides the modernisations stated earlier, YouTube is awash with Cornish wrestling footage, including a very informative history of the sport narrated by Gerry himself27. Facebook groups advertise forthcoming events, and Gerry is keen to stress the healthy nature of the sport. In all his long career, he only ever received a few ‘duck eggs’.

It’s also economical. To wrestle at a tournament on the day is a couple of pounds, jacket provided. The clubs start at U10s, membership costing around £5 after a couple of taster sessions. To register as a senior with the CWA is £10 for the season. Anyone who shows a bit of ‘game’, Gerry told me, is more than welcome.

The Cawley legacy

Gerry wrestled on after coming out of retirement, winning the heavyweight title again in 2007 at the age of 44. Gerry is the most successful Cornish wrestler – at all weights – in the last quarter of the 20th century. His children are no slouches either. Ashley was nine times heavyweight champion, and his youngest son Joe won all youth categories until a dislocated collarbone meant that ‘mother called time’.

Nowadays Gerry is a stickler, and organises the St Mawgan tournament with his brother and nephew, and admits there’s something in wrestling that just gets into your blood:

Your opponent, you might not know him, but if you go in there for a ten-minute round with somebody, you come out and you’re kindred spirits. I’ve seen it myself; I’ve run the St Mawgan tournament to this day, and I’ve seen novices go in that’ve never done it before, and after that struggle between two men…and after they come out, they’ve got their arms round each other, laughing and talking about it, it just moves people.

For all Cornish wrestling’s obvious positives, does it have a future? Gerry is very optimistic, but is more than aware of the realities his sport faces:

The world is changing. I mean, the tug-of-war teams were prolific in Cornwall then, there was sheaf-pitching all over the place, there isn’t even the fetes, fairs and carnivals in the numbers there were. But all the old things aren’t the same as they are, and Cornish wrestling is no different.

And when you look and say, yeah, it’s just another martial art, but look at the number of all the other martial arts that we don’t even remember now29.

You’ve got to have a Cornish heart to want to support the sport and come into it.

This June (2025) there will be a demonstration of Cornish wrestling at the Royal Cornwall Show. If you’re going, be sure and lend support to a sport that stretches back millenia and steadfastly remains a part of Cornish culture. Gerry’s continuing wholehearted contribution to Cornish wrestling’s existence is surely his greatest achievement.

My previous Cornish sporting hero was Tony Penberthy, the Troon, Cornwall and Northants cricketer. Find out all about him here.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Can be viewed at: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1083209555517034

- The historical and factual information in this post is heavily indebted to Mike Tripp’s authoritative Cornish Wrestling: A History, Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 2023.

- See: https://www.trevithickday.org.uk/events/

- Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8LgKtzSty4

- The opening of the Troon is reported in the West Briton, July 2 1987, p4.

- For more on Merckx, see: Merckx: Half Man, Half Bike, by William Fotheringham, Yellow Jersey Press, 2013.

- See the Cornish Wrestling Association’s website here: https://www.cornishwrestling.co.uk/

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornish_wrestling, https://kernowgoth.org/, and https://www.cornishwrestling.co.uk/rule-book/

- Image from: https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/truro-cornish-wrasslin-tournament-shows-523946

- AberFest is an annual Easter festival celebrating all things Cornish and Breton, alternating its location between Brittany and Cornwall. Other events are held throughout the year. See: https://www.facebook.com/AberFest/?locale=en_GB

- From: https://www.cornishmemory.com/item/BRA_17_004. For more on Gregory, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Gregory_(sportsman)

- Gerry’s first victory is noted in the West Briton, September 4 1975, p3.

- Image from: https://www.facebook.com/FILC.IFCW/

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Brittany. Of course, that the migrating Britons from sub-Roman Dumnonia took their wrestling to Brittany is unknowable.

- From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Stephen-in-Brannel

- Image from: https://mobile.x.com/CornishWrasslin/status/885874387970379780

- For more on Cockroft, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barry_Cockcroft

- Image from: https://www.facebook.com/stmawgancornishwrestling/

- From: https://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/lJqV8VLzT0e2Y7XeM9Abwg

- From: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTSfK_Cobb4

- For example, a demonstration at Gorran in 1980 was organised by the Cornish Nationalist Party; St Keverne’s An Gof Day in 1981 held similar. From: West Briton, May 7 1980, p15; July 2 1981, p17.

- From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masutaro_Otani

- From the BBC documentary Close Up: The Final Round?, 2000. Excerpts can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTSfK_Cobb4

- From: http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/tv_and_radio/1108228.stm

- From the BBC documentary Close Up: The Final Round?, 2000. Excerpts can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTSfK_Cobb4

- From the BBC documentary Close Up: The Final Round?, 2000. Excerpts can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTSfK_Cobb4

- See: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?ref=search&v=1348383931897147&external_log_id=f6d6827c-5f2b-4a4a-834b-e6be1eb4c1f6&q=gerry%20cawley

- From the BBC documentary Close Up: The Final Round?, 2000. Excerpts can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTSfK_Cobb4

- It’s reassuring to see that Cornish wrestling is not on the martial arts’ endangered list: https://rarest.org/sports/rarest-martial-arts

2 thoughts on “Cornish Sporting Heroes, #6: Gerry Cawley, Champion Wrestler”