Reading time: 20 minutes

Sport and journalism in the nineteenth century

As the 1800s progressed from Georgian to Victorian, Britain became increasingly urbanised. People from the countryside migrated to the burgeoning cities in ever greater numbers, and they brought their sports and games with them as well. A city or town’s rhythms, however, are very different from that of a village or hamlet. The working practices, laws and sensibilities generated by the Industrial Revolution meant that many ancient pastimes were gradually superseded by the mass spectator sports we recognise today1.

That other child of the Revolution, the popular press, contributed massively to the eventual cultural dominance of football, rugby and cycling. Tony Collins states that print culture

…not only provided publicity for and voiced the ideological aspects of sport, but the newspaper industry also initiated and organised the development of competition and other structures.

Sport in Capitalist Society: A Short History, Routledge, 2013, p59

Mass sport and the mass press evolved symbiotically; one did not beget the other. It is generally agreed that

…sport and the media are not two separate industries that have been juxtaposed coincidentally. Rather, their evolution, particularly throughout the twentieth century, has resulted in them being inextricably bound together.

Matthew Nicholson, Sport and the Media: Managing the Nexus, Elsevier, 2007, p7

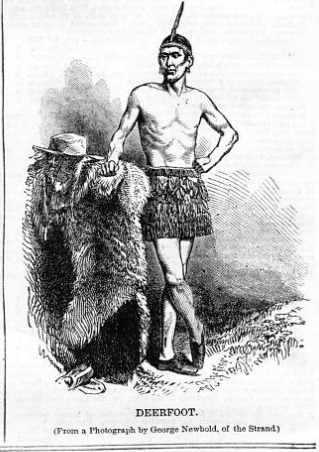

Of course, in the mid-1800s nobody could have known that the new kids on the sporting block – football, rugby and cycling – would come to dominate everyday life. The FA was only formed in 1863, the RFU in 1871. The first mass bike race rolled out of Paris in 1869 – and was won by a Briton.

Thus the major sport-oriented ‘papers of the day, such as Bell’s Life or the Illustrated Sporting News, gave equal coverage to newer, modern games as well as the older and perhaps less respectable ones. The people who read these journals, watched the games and gambled their income – the sporting ‘fancy’, as they were known – seem to have been equally comfortable with the sight, physically or in print, of soccer or rat-baiting.

And the newspapers gave the public what it wanted. You could read reports of football matches between Richmond and Civil Service College (18 a-side), or Norfolk versus Mackenzie, which lasted two hours3. Like the sound of leather on willow? A fulsome appraisal of the 1862 cricket season would be available for your perusal4.

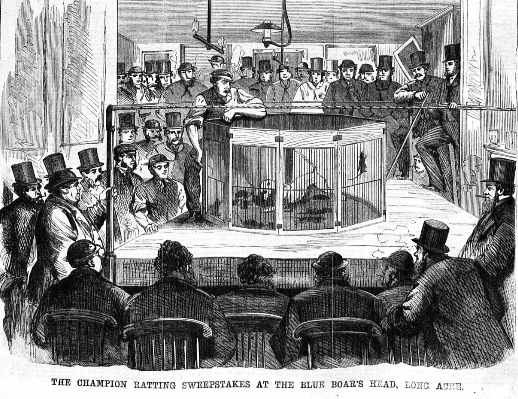

If your tastes ran more to the louche, you might consider venturing down to the Queen’s Head Tavern in Haymarket. As Bell’s Life promoted in May 1864, the noted dog ‘Pincher’ could be seen there, attempting to kill over 200 rats in ten minutes 30 seconds, ‘the shortest time ever heard of’5.

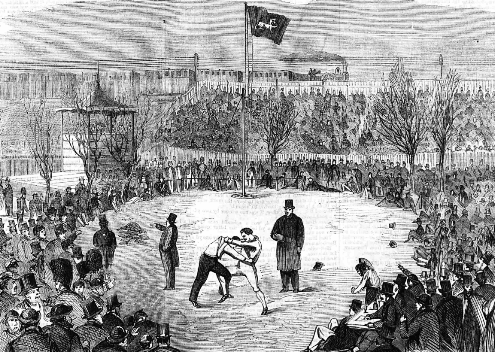

Bareknuckle prizefighting might have been illegal, but its top exponents enjoyed all the trappings of fame and rejoiced in such brutal nicknames as ‘The Tipton Slasher’6. Big fights, then as now, drew crowds from all levels of society and generated many inches of column.

When Jem Mace knocked Joe Goss cold after over two hours of pugilism for the English middleweight title (and a £1,000 purse) in 1863, Bell’s Life devoted practically an entire page to the build-up, the weigh-in and ‘the mill’ itself7. Its reporter took the opportunity to gleefully remind the reader that prizefighting is not a ‘Carnival of Brutality’, but rather

…one of the mainstays of English character in a muscular Christian point of view.

September 9 1863, p7

Bell’s is not only reporting on sport but attempting to influence the public’s opinion of it, and justify its own coverage. But if the fighters, their entourages, the 400-odd members of the fancy who spectated and Bell’s intrepid correspondent all wanted the fight to go off, the authorities certainly didn’t. Trains took the whole lot of them to a secret location near Royal Wootton Bassett, which was raided by policemen before a punch was thrown. Undeterred, the fight crowd decamped by steam power to Purfleet, where Mace beat Goss to a quivering pulp undisturbed8.

It may not surprise you, but another ancient, rural sport found its way to the metropolis in this period. For a time, it thrived. Less cruel than rat-baiting, less bloody and more lawful than boxing, yet certainly not as genteel as football or cricket, Cornish wrestling was most definitely a part of London’s sporting calendar.

The Cornwall and Devon Wrestling Society, London

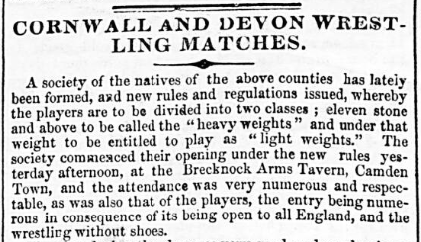

Cornish wrestling came to London in the 1820s and enjoyed popularity through to the 1870s9. Competitions were generally held over Easter or Whitsuntide and promoted, inevitably, in the pages of the sporting press.

By 1845, in an attempt to regulate the sport in its unfamiliar urban surrounds (and combat the Cumberland and Westmorland style of wrestling which had also hit London), a society was formed: The Cornwall and Devon Wrestling Society, or Devon and Cornwall, depending on which side of the Tamar you’re from. Though its competitions were open to all-comers, the Society strictly prohibited the Devonshire style of kicking your opponent in heavy-shod boots:

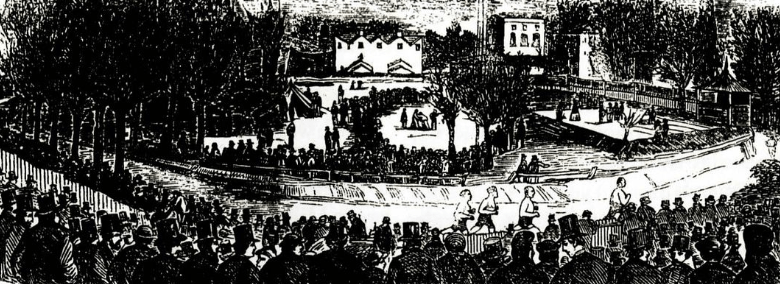

The most consistent promoter of Cornish wrestling in London was James Baum10. He was the proprietor of The White Lion pub in Hackney Wick, and owned enough land nearby to encircle a wrestling green with an athletics track. In Easter 1864, the entertainments lasted several days, including several wrestling events, mile racing and a pedestrian race11.

Baum and the Society realised they needed each other. By 1868 the latter had held 51 wrestling tournaments at The White Lion, and convened their meetings within its walls12. Bell’s Life gave Baum’s sporting extravaganzas ample coverage and, as we shall see, contributed to the success of competitions and bouts.

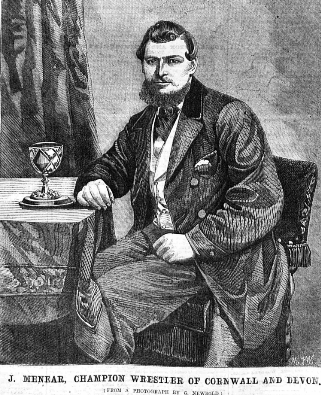

A governing body, a set of regulations, a more-or-less fixed venue, a capital investor and media promotion: London’s Cornish wrestling in the 1860s suddenly took on the trappings of a modern, commercial sport. This isn’t the place, though, to discuss why it declined, which in any case has been done admirably elsewhere13. What is pertinent here is to demonstrate how Cornish wrestling in 1860s London was so successful, and to realise this we need to trace the career of one of the ring’s leading lights: Joseph Menear.

Will wrestle any man in London – or the world

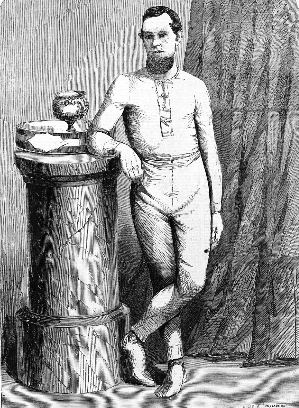

Joseph Menear (or Minear) was born in November 1837 at Tregonissey, near St Austell. His father was a miner15. Joseph stated he was one too when we find him on the 1861 census, lodging at Buckfastleigh. He was certainly only passing through Devon. In March 1861, Joseph’s wrestling at Hackney Wick. In May, he’s winning a £6 (or £600 in 2025) first prize at the Whitsuntide meet in front of a crowd of 1,80016. By September he’s sufficiently confident in his ability to place the following in Bell’s:

J. Menear will wrestle any man in London at catch weights in the Cornish and Devon style, for £5 or £10 a side. Menear can always be found at Mr Pace’s, Plough and Harrow, Battersea Fields.

September 15 1861, p7

Though Hackney Wick was his venue of choice, Joseph would always follow the money. In 1862, with his brother John also on the card, he took the first prize of £3 at Manor House Gardens, Walworth. In 1864 he featured at The King’s Arms on Whitechapel Road. Five hundred of the fancy were to be treated to a double-bill of boxing and wrestling17.

Menear was astute enough to get himself a backer, or manager, and promote himself via the media. Clearly, he was as good for Bell’s as they were for him. If the below excerpt is anything to go by, he also knew the meaning of the word hyperbole:

The organisation Joseph operated under enjoyed considerable patronage too. Prince Albert Edward, the future Edward VII, was also Duke of Cornwall and a great lover of sport. Many Cornish societies enjoyed increased exposure with a royal member of the fancy as a figurehead.

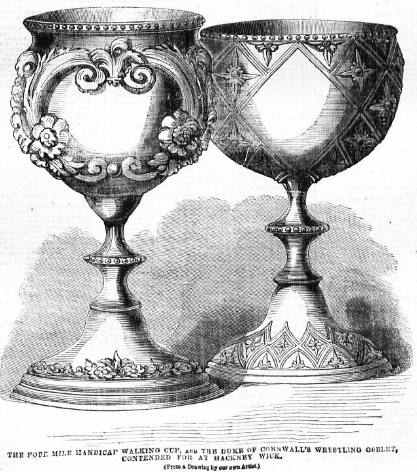

For example, one of the prizes at 1865’s Royal Cornwall Regatta was a ‘Duke of Cornwall’s’ cup, valued at £50 (or over £5K in 2025)19. The Cornwall County Races, held near St Columb in the 1860s, annually awarded its own Duke of Cornwall’s cup to a victorious jockey. In 1868, a Mr Sobey, riding on ‘Why Not’, received another Duke of Cornwall’s cup – but that’s a tale for another time20.

The Cornwall and Devon Wrestling Society did well from this royal benefactor too. For the Hackney Wick meet of Easter 1863 it was announced that

…not the least interesting event, however, will be the extra “Great Duke of Cornwall Cup” in honour of the patron of the society…

Bell’s Life, March 29 1863, p6

Bell’s further stated that the cup competition was exclusively confined to ‘natives’ of Cornwall. It’s easy to imagine Menear reading this in his digs at the Plough and Harrow (after all, that’s where he could always be found), and nodding his head in resolve. Now, that was surely a prize for any Cornishman to covet.

Three thousand spectators convened at The White Lion’s grounds on Monday, 6 April for two days of action. The preliminary wrestling bouts had taken place on the previous Friday, with Menear progressing easily, all the way to the final bout on Tuesday evening. Menear’s fellow combatant was to be a Devon man. As insufficient Cornish entrants had materialised, the organisers had thrown the competition open to wrestlers from Cornwall’s nearest neighbour21.

The Devon man, as Menear discovered, was no chump. As darkness fell and the crowds dwindled, it became evident there wasn’t going to be a conclusive winner. Who took home the Duke of Cornwall’s cup came down to the toss of a coin.

Menear called incorrectly. The Devon man won the prize22. A Cornish prize.

Menear must have been livid. If he’d lost fair and square, the pill might have been sugared somewhat, but to lose by mere chance? That would cut you deep. Menear probably had to stand there and applaud as the victor held the cup aloft.

The victor, from Devon, was John Slade.

Thus began London’s great wrestling rivalry.

A fight for the very heart and soul of wrestling

Skip forward. In 2000 Cornwall’s most successful wrestler of his generation, Gerry Cawley, came out of retirement. His mission was to defeat Glyn Jones, who had held the Cornish heavyweight belt for the previous two years. Nothing wrong there, you might say, were it not for the fact that Jones was from Devon, and a formidable black belt judoka to boot. Obviously, some felt it was time the title was returned to a pure wrestling Cornishman23.

The BBC made a documentary of Gerry’s quest (there was no fairy tale ending; Jones won), the preview of which bombastically states

…what is at stake is more than just personal pride – some say it is a fight for the very heart and soul of the sport itself…24

Gerry states in the film that

I would like to take the belt, there’s no two ways about that, just for the sake of the sport, and to make sure there was a Cornish wrassler as the champion.25

Rewinding to the 1860s, it’s not unreasonable to assume Joseph Menear held similar sentiments toward the Duke of Cornwall’s cup, and to John Slade.

Slade had pedigree, and must have come to London at around the same time as Menear, where it was noted of him that he was

…the holder of the Champion Wrestling Belt of the West of England, and is a well-known player in that part of the country.

Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, April 11 1863, p52

On the same page in Bell’s as publicity for the forthcoming slugfest between Tom King and John C. Heenan, was news of Menear’s challenge to Slade for the cup26. Menear called for £10 a side and had stumped up £2 out of his own wallet to move things along. This was all in keeping with the Society’s dictates as regards the cup. If Slade retained the trophy at next Easter’s meet, it was his to keep. In the meantime he had to ‘hold himself in readiness’ for a best-of-three backs challenge issued via – where else? – Bell’s, at six weeks’ notice. The Society also stipulated that any challenge match was to be held at The White Lion, Hackney Wick27.

Sport thrives on rivalries, challenges and controversies. It maintains public interest in that sport, inspires others to try their hand, and keeps the coffers – of both governing bodies and events organisers – full. The sport media thrives on rivalries too, but also foments them at the same time as being profitable to the industry itself. It was good for Joseph Menear and John Slade. It was good for The Cornwall and Devon Wrestling Society. It was good for James Baum. It was good for Bell’s. It was good for an entertainment-hungry public. Everybody won.

The match was set for Monday June 8 – Whitsuntide. Bell’s talked it up:

…these renowned champions will enter the ring to decide the point of the champion “wrestler” of the famed “two counties”…Slade, a proud Devonian…Joseph Menear, who has earned, and justly so, the title of “Pride of Cornwall”…an exhibition of the “ancient pastime” will take place, which bids fair to eclipse all others.

June 7 1863, p3

Bell’s was right about it getting dark. Before a ‘strong muster’ at Hackney Wick, hostilities commenced at 6pm. Three hours later, they were still at it. Slade had reckoned on disposing of Menear quickly, but the latter was more than his match. No clean backs were made, but as time wore on, and the numerous ‘dog falls’ stacked up, it became increasingly evident that Menear had the greater stamina.

The failing light forced a premature end to the bout, but there was to be no coin-toss this time. Menear was confident, and Slade ‘much distressed’ as the rematch was set for Saturday June 20. The Bell’s columnist could barely hide his delight:

The champions having played in such magnificent style…adds much additional interest to the match among those who are admirers of the sport…

June 14 1863, p6

This time round, Menear was in fine fettle, and Slade, the fancy reckoned, looked off-colour. They weren’t wrong. Forty minutes in, Menear gained a dominant grip on Slade’s jacket, and slammed him on to the turf. Menear was hunting one more back like that, and the Duke of Cornwall’s cup would be his. Slade may have been unfit, and he may have been hurt, but he was still a winner. The only thing for it now was all-out attack.

Slade attacked for over an hour, but to no avail. Menear’s first back proved to be the winner, and would later see Slade hospitalised. With a severely bruised side, the Devon man had to retire. Menear had brought it home29.

Then the war of words began.

Champion wrestler of Cornwall and Devon

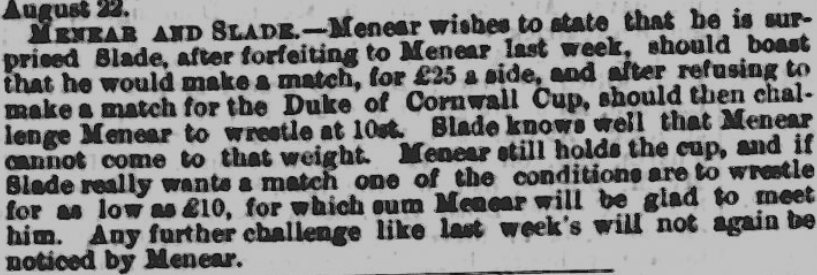

As soon as Slade was able, he was challenging Menear, but on his own terms:

Menear could brush off the challenge. Under the Society’s rules, any wrestler of 11st and above was a heavyweight. Menear wrestled as such, and had moreover won the cup at that weight31. Surely a mere challenger should accept the terms of the champion? Menear certainly thought so.

It’s probable the two men never wrestled each other again. Even in 1867 there was talk of a wrestling ‘superfight’, with Slade and Menear supposed to meet at The Spotted Dog on The Strand, and agree to terms. But nothing came of it32.

Slade would haunt Menear. At the Society’s 51st Hackney Wick meet in 1868, he was present when Joseph stepped on to the turf for the title bout against another St Austell man, W. Harper. Each could appoint an umpire; Menear selected his brother. Harper, perhaps aware of the two men’s animosity, asked Slade to protect his interests. It initially proved a canny move:

After they had been wrestling two minutes, Slade objected to Menear’s hold…

Bell’s Life, April 18 1868, p10

Menear, who surely by now had seen it all, was probably anticipating something of the sort from Slade, and wouldn’t be phased. Indeed, the piece of gamesmanship appears to have fired him up. A minute later, Harper was on his back, and Menear was acclaimed ‘Champion of the London ring’ for the eighth time running. One imagines he gave Slade the eye33.

Even in the 1880s, Slade was still sniping at Menear in print, claiming he was the better man34.

In London wrestling terms, though, Menear was the better man. His prowess was unmatched. His fame reached back to Cornwall, where he was the star draw at a Marazion tournament in 1868. To be honest, the Cornish scene needed a boost:

Cornish wrestling within the last 20 years has fallen very much into disuse in the county where one would expect to find it at home.

Bell’s Life, May 2 1868, p7

As Menear’s sojourn to the land of his birth illustrates, the top grappling talent was no longer to be found in Cornwall, but in London. Problem was, Menear was too good for the city scene as well.

No better known place in all London

As early as 1866, Easter crowds at Hackney Wick had dwindled to just 1,00036. Although to a ‘certain section of provincials’,

…there is no better known place in all London than Mr Baum’s recreation grounds…

Uxbridge and West Drayton Gazette, March 3 1868, p7

…more seasoned city dwellers were patently looking elsewhere for their sport. Menear’s wrestling dominance throughout The White Lion’s heyday may have been a contributory factor. If sport becomes predictable – and Menear being victorious was getting pretty predictable – it ceases to be entertaining. The Society, perhaps sensing this, met in May 1868. Unbelievably, there were calls to bar Menear from their next meet, in a quest for a new champion. The Society must have forgotten just who had put their name in lights these past few years, but in the end a slightly less cynical solution was sought. They would find a man, that could beat the man37.

One who did offer his services was John Slade, but as before, no bout materialised38. Though his older brother John wrestled at Hackney Wick in June 1868, Joseph wasn’t present. He wrestled sporadically on into the 1870s, but his glory days were over. By 1880, he and his old foe were umpiring a tournament at Lambeth Baths39.

In the 1921 census, Joseph was living alone in Hackney, yesterday’s man, a retired night watchman. He died in 1923, aged 8640.

The White Lion is permanently closed, the days when it was one of London’s premier sporting attractions practically forgotten41.

The trophy with which Joseph’s name is forever linked – the Duke of Cornwall’s cup – had been bequeathed him by the Society in recognition of his achievements42. Sadly, it appears to have been lost, yet one hopes that, some day, it will show up. Such things do happen. In fact a Cornish trophy from the 1860s was discovered in California in June 2025. Read all about that by clicking here…

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Tony Collins, Sport in Capitalist Society: A Short History, Routledge, 2013, p14-20 and 48-59.

- From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Moore_(cyclist)

- Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, February 7 1863, p428, and November 18 1865, p589.

- Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, January 10 1863, p396.

- May 14 1864, p7.

- The Slasher’s real name was William Perry. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Perry_(boxer)

- September 9 1863, p7.

- For more on Mace, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jem_Mace

- Much of this section is indebted to Mike Tripp’s Cornish Wrestling: A History, Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 2023, p68-73 and 81-3.

- For more on Baum, see: https://www.layersoflondon.org/map/records/athletics-at-the-white-lion-hackney-wick

- Bell’s Life, April 2 1864, p7.

- Bell’s Life, April 4 1868, p8, and May 9, p7.

- See Mike Tripp’s Cornish Wrestling: A History, Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 2023, p74-95.

- Image from: https://www.layersoflondon.org/map/records/athletics-at-the-white-lion-hackney-wick/gallery/3

- From: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=baptisms&id=6849430

- Bell’s Life, March 31 1861, p8, and May 26, p6.

- Bell’s Life, April 27 1862, p7, and May 14 1864, p7.

- Image from: https://newsfeed.time.com/2013/03/09/royal-diaries-reveal-the-life-of-edward-vii-in-the-1800s/

- Bell’s Life, August 26 1865, p1.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 21 1868, p5. The story of John Hicks Sobey and his cup is a fascinating one: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2025/08/10/john-hicks-sobey-and-the-duke-of-cornwalls-cup-1868/

- Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, April 18 1863, p69.

- Bell’s Life, April 12 1863, p10.

- See my interview with Gerry here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2025/06/07/cornish-sporting-heroes-6-gerry-cawley-champion-wrestler/

- From: http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/tv_and_radio/1108228.stm

- From the BBC documentary Close Up: The Final Round?, 2000. Excerpts can be seen here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eTSfK_Cobb4

- April 12 1863, p7. For more on Tom King, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_King_(boxer)

- Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, April 18 1863, p69.

- Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, March 22 1862, p12.

- Bell’s Life, June 28 1863, p3 and 6.

- Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, April 2 1864, p1. For more on Newbold’s work, see: https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp58908/george-newbold?role=art, and https://www.abebooks.co.uk/History-Great-International-Contest-HEENAN-SAYERS/18280495198/bd

- Sun (London), May 13 1845, p7; Bell’s Life, May 4 1862, p6.

- Bell’s Life, November 30 1867, p7.

- Bell’s Life, April 18 1868, p10.

- Sporting Life, November 13 1883, p1.

- From: https://www.flickr.com/photos/tetramesh/8665593363/in/photostream/

- Bell’s Life, March 31 1866, p8.

- Bell’s Life, May 9 1868, p7.

- Bell’s Life, June 20 1868, p7.

- Bell’s Life, June 6 1868, p10, October 21 1877, p9, December 1 1877, p9, January 31 1880, p9.

- Civil Registration Death Index 1916-2007, vol. 1b, p302.

- See: https://www.layersoflondon.org/map/records/the-white-lion-wick-road-hackney-wick

- Illustrated Sporting News and Theatrical and Musical Review, June 12 1869, p3.

One thought on “Joseph Menear and Cornish Wrestling in London”