Reading time: 20 minutes

We haven’t had a stoppage like this for ages – not since the week before last ~ I’m All Right Jack (1959)

We’re organised, see? ~ Hue and Cry (1947)

Workers of the world, unite

In the years leading up to World War One, Britain experienced labour unrest on an unprecedented scale. Winston Churchill sent the infantry into the Welsh valleys as 30,000 striking miners ground the coal industry to a halt. Gunboats patrolled the Mersey, menacing intransigent dockers.

The country’s working class demonstrated steely resolve. London’s stevedores only returned to work under the threat of their children being left to starve. Railway workers refused to handle goods destined for Ireland, in a show of solidarity with their striking comrades in Dublin. All the unrest, observes one historian,

… demonstrated for the first time since the days of the Chartists that the working class could take the ruling class by the throat.

Tony Collins, Raising the Red Flag: Marxism, Labourism, and the Roots of British Communism 1884-1921, Haymarket Books, 2023, p45

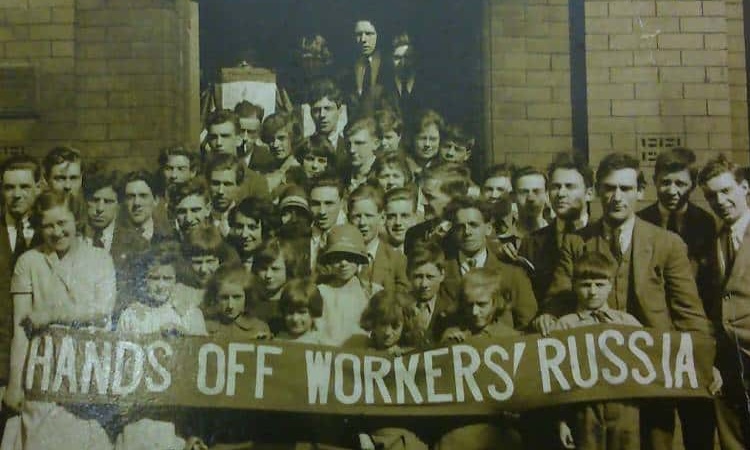

The Russian Revolution of 1917 and the subsequent seizure of power by the Bolsheviks raised the bar of socialist ambition. Britain’s leading communists undertook arduous journeys to the new workers’ paradise and sought the advice of Comrade Lenin. In the summer of 1920, the Communist Party of Great Britain was founded in London.1

These turbulent years saw a genuine commitment from vast swathes of the British working class toward protest and organised walkouts. Anything could be achieved by the simple act of downing tools. For what sadly seems like the last time in labour history, Britain’s proletarians had the whip hand in employment relations and exploited this advantage to its fullest.

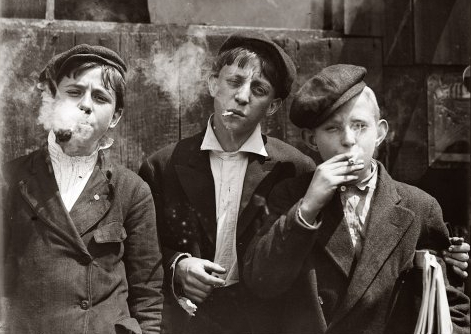

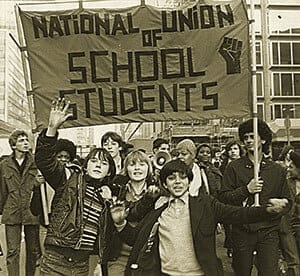

Seeing what could potentially be achieved by the politics of striking, the younger generation followed suit.

Abolish the cane

In 1911 over 60 towns in the UK experienced school strikes, mainly over the issue of corporal punishment.4 Several places of learning in the Edgehill district of Liverpool suffered walkouts, scholars committed acts of vandalism on protest marches and loyalist students were thrashed. The strikers’ demands were as follows:

An extra half-day holiday each week.

Abolition of the cane.

No school fees.

Monitors to be paid one penny each week.

Cornish and Devon Post, September 16 1911, p3

The ringleader shortly discovered the cane was still held in high regard by the school authorities, and the newspapers made light of the whole affair, describing it as a ‘Comedy’.5 This serves to belittle or marginalise the efforts of the children who were trying to improve their lot, a recurring feature of strike reportage. Dismissing a school strike as little more than a spontaneous prank does such acts a disservice. We would do well to recall that the longest running strike in British history – from 1914 to 1939 – centred around a school.6

Considering Cornwall, in 1914 the boys and girls of Bugle Council School organised themselves. It was their opinion that a new teacher had been treating them too harshly. To ‘convince the authorities’ of the gravity of their plight the children appointed a deputation, left the school to parade through the streets of Bugle and presented themselves at the school manager’s home.8

The juvenile strikers had chanted slogans – and taken inspiration – from the recent clay strike in nearby St Austell, but there was no police baton-charge in Bugle. Indeed, the strike only lasted an afternoon.

Blisland’s schoolchildren also walked out in 1914, as did their compatriots at Lanteglos-by-Fowey in 1919.9 By far the most serious Cornish school strike, though, took place at Polruan in 1922.

Polruan Boys’ School

The strike is important as it reveals, for better or worse, certain features of Cornish society at the time. Most evident is a fear or mistrust of outsiders that borders on the xenophobic (many would argue that this is an integral part of the Cornish character). There is also a semi-pathological mistrust of authority, and that that authority is inherently venal and corrupt. Post-war British and European society was bitterly divided between workers and employers, haves and have-nots, patricians and plebeians:

… crowns and thrones had perished, aristocracies had been vanquished, great estates and splendid possessions had been confiscated, and venerable titles abolished … Ordered, stable, traditional societies had been torn apart, as revolution was followed by civil war and anarchy …

David Cannadine, Class in Britain, Penguin, 2000, p127

Of course, Britain did not experience revolution, civil war or anarchy. But that doesn’t mean to say that many people at the time actively fomented such a state of affairs.

Another factor is the reverence held by many communities for those who had proven themselves in the recent conflict, in direct contrast to those (shirkers, conscientious objectors, cowards) who hadn’t. The final element to consider is the Polruan parents’ influence on their disgruntled offspring. Did the idea to strike form in the adults’ minds first, or did the children take the lead?

Boasting a total of 65 attendees, in December 1921 the school’s headmaster, Mr Widlake, was due to retire. Of the 12 candidates seeking his post, there were two front-runners.

James R. Roberts was in his late twenties and originally from St Agnes; he was the assistant head at Polruan. Although he had only recently gained his teaching certificate, Roberts had ten years’ experience in the job, at two other Cornish village schools, Millbrook and Fourlanesend. Popular with his pupils, Roberts also had a touch of glamour. He had seen action on the Macedonian Front during the war and had been wounded in 1918. He already had Mr Widlake’s vote for the job. In short, Roberts’ application was compelling.11

Samuel L. Tipping, a certified teacher from 1905, was 39 and from Liverpool. He had married a Polruan girl and wanted to move his family back to Cornwall. During the war, he had been on home service with the Royal Garrison Artillery. The only applicant from outside Cornwall, Tipping had vast experience of inner-city schools and must have been a teacher of the highest calibre.12

The six school managers, all locals, met before Widlake’s departure to appoint the new headmaster. The selection was to be informed by the following criteria: experience, qualifications and war service. The successful candidate was voted in by four to two, and the announcement was made on 8 November.

Polruan Boys’ new headmaster was to be Samuel Tipping. He would receive a higher salary than if Roberts had been awarded the post, which was taken to mean a greater strain on the ratepayers’ wallets.13

Then the problems started.

Flying pickets

Almost immediately, the parents took action. A deputation sent a written appeal to the school managers, requesting they rescind their decision and appoint Roberts as the new head. When this fell on deaf ears, they appealed to the County Education Authority, with similar results.

The parents then requested the managers meet them with the aim of coming to an agreement, but this was declined. The authorities’ stonewalling was a mistake. A petition, signed by 118 Polruan inhabitants, was sent to the managers on 3 December. The final paragraph carried a threat:

We again appeal to you to earnestly do your utmost to appoint the right man in the right place, thus preventing any calamity which might take place on the re-opening of the school after the Christmas holidays.

Cornubian and Redruth Times, January 26 1922, p5

An uneasy truce descended over Polruan.15

Then it was the children’s turn.

Monday, 9 January 1922. When Polruan Boys’ School reopened after the seasonal break, only half the 60-odd pupils showed up.

The managers arrived to formally welcome Tipping to his new post, then rapidly made themselves scarce. Trouble was on the way, in the form of around 30 pubescent protest marchers.

After striding up and down Polruan’s streets, chanting the slogans which had been painted on the their banners (‘Up Roberts!’ and ‘Down Tipping!’), the boys formed a picket outside the school.

For the next six hours, a miniature riot took place as the strikers made their presence known. The school was bombarded with stones and turves, while some of the bolder lads scrambled up the window ledges and gave their feelings full voice.

Inside, lessons were impossible. Tipping must have been wondering what the hell he’d done to merit such a reception. A local newspaper made it plain. Most of Polruan were incredulous that Roberts had lost out, seeing as he was

… very popular with the boys and the inhabitants, the latter of whom considered that as he is a Cornishman and had been on active service in Salonika he should have been appointed.

Cornish Guardian, January 13 1922, p5

The following day, Polruan Boys’ School was under police guard. An extra officer was drafted in, and he spent most of his shift confiscating numerous banners and flags from the still-parading children. Little good it did him; no sooner would he relieve one striker of their placard then it would be replaced by a budding adult.16

Had the children planned the protest and strike themselves, and their parents merely provided their equipment? Or had the children been directed to take the actions they did?

Either way, this was obviously no spur-of-the-moment appeal. The Polruan School Strike had a certain level of complicity on the part of the children and their parents. Convincing 30 kids to spend the best part of the day marching around outdoors – in January – would be difficult to achieve had not the children felt as passionately about the appointment of Tipping as their elders.

One thing we must also realise is that no adults were ever reported to have taken part in the protests, no matter how much they were involved in the preliminary objections.

This was a children’s act of defiance, which their parents rubber-stamped.

School’s out

The strike was quickly condemned in the press as undemocratic and ill-informed. In a political democracy,

… we must be very careful how far we object to the decisions come to by duly elected public authorities … we don’t get rid of them by incitement to disorder and law-breaking.

Cornish Guardian, January 20 1922, p5

Furthermore, the same columnist stated that the strike ‘has been given an importance which it hardly deserves.’ It is with great irony, then, that three pages later in the same edition of the Cornish Guardian, we discover that one of their stringers had visited Polruan on Thursday, 17 January, to better cover the ‘scene of action’.

The only action that day, with the strike now in its second week, was stirred up by the reporter themselves. Most of the 24 striking boys had gone winkle picking. When some did appear, they appeared nonplussed by the visitor’s erroneous insistence that their travelling companion was a detective from Scotland Yard.

On the front door of a local matriarch, though, was chalked the legend ‘Up Roberts, down Tipping’, and the inhabitant needed little prompting to speak plainly on behalf of Polruan’s community:

Why should the managers appoint Mr Tipping because his wife is a Polruan girl? Why didn’t they appoint Mr Roberts, who is a Cornishman, instead of a foreigner from Liverpool?

Cornish Guardian, January 20 1922, p8

The lady also asserted that Tipping had ‘got round’ the managers when he visited Polruan the previous summer. The authorities ought to be defied, because they had gone against the wishes of the ratepayers. The boys would ‘never’ go back to school with Tipping at the helm.

The Guardian‘s journalist found the school itself peaceful, albeit with two policemen standing guard, chilled to the marrow. The dispute was at a stalemate: the boys would not return unless Roberts supplanted Tipping, which is something the authorities were powerless to do. Talk had replaced action.

There were rumours of the girls’ school walking out in sympathy, and those boys attending lessons were pejoratively described as ‘black legs’ by the strikers. The reporter fomented a chorus of boos and jeers from a crowd of 50 locals who were sympathetic toward the strike, but you got the sense it was only going to end one way.

We the undersigned

The strike was comparatively easy to neutralise. Its young protagonists and the their backers were not involved in a more traditional dispute of employer-employee relations and were thus neither members of, nor recognised by, any trade union.

Their grievance as they saw it – the appointment of the wrong man as headteacher – had none of the universal appeal of the 1911 school strikes, which focused on the issue of corporal punishment. No solidarity walkouts, even from Polruan Girls’ School, would be forthcoming.

The strike was therefore localised and its participants isolated. Even within the school itself, only 24 of the 65 boys remained steadfast in their conviction. Apparently nobody considered clubbing together to hire a stand-in teacher, or take it upon themselves to provide some tuition for the strikers. It would have reinforced their status before the authorities.

On Monday, 23 January, with the strike about to enter its fourth week, twenty Polruan parents made their way to Liskeard Police Court. The charge contained in the summons, issued on the 16th, was that of

… failing to send their boys to school.

Cornubian and Redruth Times, January 26 1922, p5

Immediately the summons had been received in Polruan then the prosecutor received the following in a letter:

We the undersigned as parents and ratepayers declare that our boys will not attend school at Polruan until Mr Roberts is appointed headmaster of the Boys’ School, and Mr. Tipping withdrawn from the school.

Cornubian and Redruth Times, January 26 1922, p5

For all the bombast, the parents unanimously pleaded guilty and coughed up their five shilling fines. But they had their say in court.19

One remarked that it was unfair Tipping got the job. The word in Polruan was that he had been assured of the post in the summer; Mrs Tipping had told all who would listen. The whole thing was a fit-up.

Walter Olsen, who had a young teenager and a five year-old out on strike, declared it was ‘nothing but right’ that Roberts should have got the job.

Mariner Henry Smith, whose son William was ten, alleged that family influence had got Tipping in. The lack of transparency was also frustrating:

We asked the managers to give us a public meeting …

Cornubian and Redruth Times, January 26 1922, p5

His sentiments were echoed by Roderick Dow, an unemployed docker from Antigua. John Tomlin, a boatman whose two lads had spent the best part of a month at home, told the court that Roberts would have made the school ‘a little heaven’. Frank Thomas said his boy had ‘greatly improved’ as a scholar under Roberts, and ‘as a Cornishman’, wanted him in charge.

Archibald Allen, a GWR employee, had two sons on strike. He stated that

It is a bad job if you have to go out of Cornwall for schoolmasters … I should think that there are just as good men in Cornwall as in Liverpool for educating the boys.

Cornish Guardian, January 27 1922, p7

All present were reminded of the illegality of their actions. The parents should have employed ‘constitutional means’ to vent their dissatisfaction. Any school appointment was the business of the managers, who had, after all, had picked the man best qualified. The managers in turn had been elected by the parents themselves, who were also told that the rates would not increase.

That wasn’t quite the end of the affair.

Lighting a fire

The boys would return to school on the Tuesday, but one adult remarked darkly in Liskeard that Polruan had been set ‘on fire’.21 Luckily it didn’t get that far.

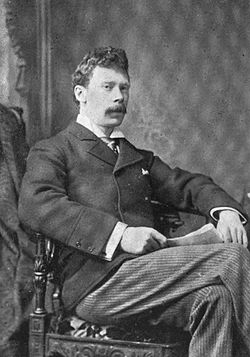

It is unclear who was abroad in Polruan on the Monday evening after the hearing, parents, children, or both. What is clear is that an unpleasant mob gathered outside Tipping’s house, challenging him to come out and face them. The distinguished literary figure, Sir Arthur Quiller-Couch, then of the Cornwall Education Authority, heard of the disturbance over in Fowey and sent police reinforcements over to break things up.22

‘Q’ realised bridges needed to be built and the air cleared. He would chair a meeting of the education committee and a deputation of the Polruan parents on Friday, 24th January. Beforehand, though, it became apparent that Roberts should not have even been considered for the job: under the regulations of the time, his lack of college training meant he was not eligible for the job ‘under any circumstances.’23

The committee, with Roberts, Tipping and Polruan’s vicar in attendance, faced a grim set of ratepayers, who regarded them with ‘deadly earnest’.24 You cannot help but think such a meeting should have taken place before Christmas 1921. Such laxity on the part of the authorities surely contributed to the discontent evident in Polruan.

Q and his cohorts were certainly taken aback by the organisation and resolution of their opponents. Their objections to Tipping’s appointment were listed point by point. Furthermore, evidence was presented that ‘personal influence’ had secure Tipping the post. His wife was related to at least two of the managers, and Tipping had even canvassed the vicar to champion his application. All this was stringently denied.

All Tipping had done, in reality, was enquire about the particulars of the job, as any sensible man would. He was also called on to refute the story that he had personally caned all the strikers when they finally returned to his school. That Mrs Tipping had used her family ties to get her husband appointed was baseless.25 Q closed the meeting by asserting that his authority would not be bullied, and that Tipping at least deserved a chance – especially as Roberts was ineligible. Ultimately, Tipping’s appointment was upheld.26

The people of Polruan, it was argued, hadn’t shown the best of themselves:

… it [the strike] was in no respect creditable to the Cornish character … actuated by narrow and ignorant prejudices … This is carrying the distinction between Cornwall and “foreigners” a great deal too far, and by this time the people of Polruan have got to know it.

West Briton, February 2 1922, p4

Perhaps so, but the situation only got out of hand thanks to the authorities refusing to listen to the people of Polruan in the first instance.

The aftermath

James Roberts, who it must be said seemed to have been rather embarrassed by the events, left Polruan in May 1922 to take up a post in Newquay. He died in Wales in 1956.28

Samuel Tipping, who overall maintained a dignified silence over the strike, took his chance and eventually proved himself the right man for Polruan. He was active in the local football club, and a vocal, forthright presence at local council meetings. The village he made home was always put first, and he was a fixture at rural committee meetings into the 1930s.29

But to some, he would always be an outsider. As late as 1934 locals sought to attack him in print over his activities as Lanteglos parish’s representative on the Liskeard Rural District Council. By now, though, Tipping had his champions. They would justifiably point out that Polruan, unrepresented at Liskeard for 18 years before Tipping took up its cudgels, had been in a state of ‘hopeless neglect’ before his arrival.30

He died in Devon in 1960.31

By then the school, erected in 1870 (a significant year for British education), had ceased to exist. On 19 July 1940, a lone German bomber machine-gunned Polruan’s harbour, and then dropped its cargo over the village, scoring a direct hit on the building. Polruan had finally been set on fire.

As this occurred at teatime, the school was deserted and nobody was injured. Standing as a ruin until it was finally demolished in 1958, the locals recalled with glee ‘the days of the great strike’ as the bulldozers moved in.32

Today, a car park on St Saviour’s Hill covers the site.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Tony Collins, Raising the Red Flag: Marxism, Labourism, and the Roots of British Communism 1884-1921, Haymarket Books, 2023, p190-224.

- See: https://thecommunists.org/2025/04/30/news/communist-work-in-trade-unions-resolution/

- See: https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2010/06/newsies-vs-world-newsboys-strike-of.html

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/School_strikes_of_1911. For more on the history of school strikes, see: https://socialistworker.co.uk/in-depth/school-s-out-when-we-learned-to-strike/

- Cornish and Devon Post, September 16 1911, p3.

- This happened at Burston in Norfolk. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burston_Strike_School

- For more on the clay strike, see: https://www.tolpuddlemartyrs.org.uk/history/hard-times-and-unrest/1913-china-clay-strike

- St Austell Star, February 26 1914, p5.

- Newquay Express, May 29 1914, p6; West Briton, December 4 1919, p2.

- See: https://chattingcritically.com/2022/09/07/school-children-resist-in-1911-a-historical-precedent/

- Cornish Guardian, January 20 1922, p8, 1921 census. Roberts’ war service records also available on Ancestry, but sadly in many places the writing is faded and illegible.

- Cornish Guardian, January 20 1922, p8; January 27 1922, p7, 1921 census.

- Cornish Guardian, January 20 1922, p8; January 27 1922, p7; Cornubian and Redruth Times, January 26 1922, p5.

- Still from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I64ewblmTUY&t=161s

- Newquay Express, December 2 1921, p6.

- Cornish Guardian, January 13 1922, p5.

- See: https://libcom.org/article/childrens-strikes-1911-dave-marson

- See: https://socialistworker.co.uk/in-depth/school-s-out-when-we-learned-to-strike/

- The details from the court hearing are taken from: Cornubian and Redruth Times, January 26 1922, p5, and the Cornish Guardian, January 27 1922, p5. The parents’ backgrounds are taken from the 1921 census.

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arthur_Quiller-Couch

- West Briton, January 26 1922, p6.

- Cornish Guardian, February 3 1922, p7.

- Cornish Guardian, February 3 1922, p7.

- Cornish Guardian, February 3 1922, p7.

- Cornish Guardian, February 3 1922, p7.

- Cornish Guardian, February 17 1922, p6.

- See: https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/history/luftwaffe-attacks-cornwall-destroyed-hospital-8219716

- Cornishman, May 10 1922, p3; England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995.

- Cornish Guardian, September 14 1923, p5, April 26 1928, p13, January 10 1929, p2, April 2 1931, p14.

- Cornish Guardian, March 29 1934, p15

- England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1995.

- Cornish Guardian, May 8 1958, p13. For more on the Education Act of 1870, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elementary_Education_Act_1870