Reading time: 15 minutes

The Hook1

The men of substance from Bristol were on to a good thing. There was William H. Brunt, a music-seller from St Augustine’s Parade. There was Mr Hyde, a banker, and William Chilcott, a bullion merchant. There was James Bigwood, a merchant on Great George Street2. There was Mr Atchley, a solicitor, and a Mr Pring. They were businessmen, with experience of the stock market, and they had travelled to Cornwall to view, and inspect, their latest investment: South Wheal Leisure Mine (not to be confused with the considerably larger Wheal Leisure concern), at Penwartha Coombe, Perranzabuloe, near Bolingey.

What they saw, in June 1865, did not disappoint. Miners were hard at work, the main shaft had a fully-functioning engine housed above it, and the impression that the whole concern was a family-run business must have further assured them. The purser’s cousin owned the account-house and the land around it; Brunt for one met the purser’s elderly father, and was quite charmed. The purser had also shown Brunt, and maybe the other investors, samples of ore from Wheal Leisure before their journey to Cornwall. He had also made it known the mine was very profitable, not in debt, and that a ‘call’ on shareholders to make up any financial shortcomings incurred during operations, was highly unlikely3.

The investors had seen what they wanted to see, and doubtless strolled away from the slopes of Penwartha Coombe anticipating some easy money to be had from the backs of these Cornish tinners. Brunt, for example, had purchased 125 shares in South Wheal Leisure, paying the purser £532 for them. Furthermore, the purser had intimated that he was starting a new mining venture, to be called Bolingey Hill Consols, which Brunt, amongst others, should be anxious to invest in. Brunt quickly snapped up 500 Bolingey Hill shares, for £200.

And why not? The purser, a disabled Cornishman in his mid-forties, resided at a notable Clifton residence in Bristol, employed a liveried servant, tooled about the town in a coach and pair, and presented the very image of a successful Victorian businessman. He splashed his cash on diamond rings, harmoniums, and impressive quantities of port and sherry. He told all who would listen in Bristol that his income would soon be around £20-30,000, thanks to his shrewd mining ventures, and that buying shares in his mines was, in modern parlance, a no-brainer.

The problem for the Bristolians was this: the purser in question was Paul Rabey, the Younger.

The Player

Though virtually unheard-of nowadays, Paul Rabey (or Raby) the Younger is deserving of the accolade of Cornwall’s most notorious con-man. Born in Gwennap, in 18185, and raised at Radnor, near Scorrier, in his day he was recognised as

…one of the cleverest men in the county of Cornwall in mining transactions, which was saying a great deal.

Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 29, 1866, p8

Rabey was blessed with an incredibly “acute” mind, and one prosecuting lawyer had to grudgingly admit that he was as able

…to conduct business for his own benefit as any man that he had heard of in the whole course of his life.

Western Daily Press, April 6, 1866, p3

Shame, then, that he was as crooked in his business ministrations as the night is dark.

Wherever he went – and Rabey was as peripatetic as he was a rogue – he left ruined dreams, decimated bank accounts, and simmering resentment. In 1856 he was to appear in York as an insolvent debtor; his previous addresses up to this point were listed as Sheffield, two residences in Birkenhead, another two in Anglesea, three in Manchester, Kingston-Upon-Hull, Bath, another two in London, Liverpool, New Brighton (Merseyside), Chelsea, and Westminster. Oh – and Portreath6.

Such was the regularity of his appearances in various law courts throughout the 1860s, that reports of these hearings in the ‘papers carry their own sense of weary resignation. For example, the heading

appears at least twice7. Or this, from the London Morning Herald8:

It got so that his activities needed no introduction to the regular reader9:

Such was Rabey’s notoriety, he was actually cited in public lectures that sought to caution the unwary public on the dangers of bubble-schemes, market rigging, and various dubious business practices10. People taken in by his get-rich-quick enterprises were embarrassed to admit to being so foolish, even when under oath in court11.

All of which begs the following questions: how did he operate, and how did he get away with it? Some historical context is needed.

Victorian White-collar Crime

The Industrial Revolution and expansion of Empire changed British society for ever. It also gave rise to a new variety of financial crime, known at the time as ‘high art’ crime. The railway boom of the 1840s saw a number of attempts to exploit the trend for investment, and many fraudulent ‘bubble’ companies were set up solely to dupe unwary financial speculators. That people were easily gulled by these outwardly respectable crooks-in-suits was largely due to the prevailing culture of the era, namely a belief that all members of Victorian society’s respectable upper- and middle-classes were just that: respectable and, above all, honest.

One of the central tenets of the newly-formed police force was to protect the middle- and business-class from what was seen as society’s criminal elements, ie the lower, working-classes. Crime therefore came to be viewed as the preserve of poor people, committed on the better-off: it would be unthinkable for a gentleman, or gentlewoman, to break the law.

But break the law, they did, with financial fraud becoming the crime of choice for ‘respectable’ criminals. London bankers Strahan, Bates and Paul misappropriated their clients’ money in 1855; likewise the directors of the Royal British (1858) and City of Glasgow (1878-9) Banks stood in the dock to answer for their embezzlements. One of the ‘brains’ behind the Great Train Robbery of 1855 kept a fashionable address in Shepherd’s Bush; another member of the gang was a corrupt barrister13.

On the whole, though, people trusted ‘respectable’ citizens because they appeared to be just that – respectable14.

No one appeared more respectable than Paul Rabey the Younger, and this appearance could not have been further from the truth.

Indeed, his career could have been written by Charles Dickens. Think of the younger Ebenezer Scrooge, and, like Scrooge, in the end, Rabey’s past caught up with him. But there was to be no redemption.

It’s beyond the scope of these posts to itemise every shady deal and every shameless con-operation Rabey carried out15. Instead, I’m going to focus my attention on the years 1864-1872, the later period of his colourful career. This ought to serve to illustrate the (often questionable) business practices of the high Victorian era, and serve to remind the reader that mining wasn’t just a risky business for the men below the ground16.

As with my previous work on the Cornish Food Riots of 184717, I’ve divided my work on Paul Rabey the Younger, entitled They Died With Their Shoes On18, into separate posts, of which this is the first:

Part two, Paul Rabey and the False Imprisonment, can be read HERE.

Thanks for reading and following

References

- The narrative for this section is taken from the Royal Cornwall Gazette (hereafter RCG), 29 March 1866, p8, and the Western Daily Press, April 6 1866, p3.

- 1861 census.

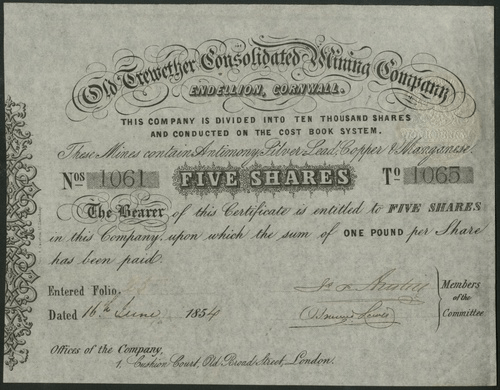

- For a brief explanation of the Cost Book system in Cornish mining, see John Rowe, Cornwall in the Age of the Industrial Revolution, 2nd enlarged edition, Cornish Hillside Publications 1993, p23-5.

- See https://spink.com/lot/18021000293

- England, Select Births and Christenings, 1538-1975, film #1595598, ref ID p139, Ancestry

- North Wales Chronicle, September 13, 1856, p2. Debtors’ known residences were listed publicly in the hope any creditors in those areas would be made aware, and could act accordingly.

- RCG, November 9, 1865, p8, and March 29, 1866, p8.

- March 28, 1866, p8.

- RCG, August 9, 1866, p5.

- Such a lecture was advertised in the Western Daily Press, September 10 1868, p1. The lecturer, Mr H. I. Brown, was one of Rabey’s victims; see the Bristol Times and Mirror, 12 & 13 August 1868, p3.

- See the Western Daily Press, May 18, 1866, p2.

- See: https://institutionalhistory.com/homepage/prisons/major-prisons/woking-prison/woking-invalid-convict-prison-inmate-list/william-strahan/

- Michael Crichton fictionalised the story of The Great Train Robbery; it was also made into a memorable 1978 film starring Sean Connery and Donald Sutherland.

- See Sarah Wilson, “Fraud and White-collar Crime: 1850 to the Present”, in Histories of Crime: Britain 1600-2000, ed. Anne-Marie Kilday and David Nash, Macmillan, 2010, p146-51.

- Kresen Kernow hold records of his earlier exploits, references as follows: STA/693c/1441, 1443, 1446, 1460.

- See “A Risky Business: Death, Injury and Religion in Cornish Mining 1780-1870” by John Rule in his book Cornish Cases (Clio, 2006), for more on the hardships of Cornwall’s mining population.

- See: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2022/01/09/the-cornish-food-riots-of-1847-background-and-context/

- Rabey once wished his enemies would “die in their shoes!”. The reason for this will be explained in my final post. (See: The Cornubian and Redruth Times, October 16, 1868, p4.)

Can’t wait for the next installment

LikeLike

Looking forward to the detail of Rabeys scandalous dealings.

LikeLike

Thank you – very interesting. I am waiting for the next part.

LikeLike

I am pleased to see this, as I have come across Paul Rabey in my researches on the London & South Western Bank.

John Dirring

LikeLike

Thank you for covering cousin Paul

LikeLike

My pleasure! Fascinating character…

LikeLike

My husbands GG Grandmother was a sister to Paul Rabey , she married John Nathaniel Earle they had a printers and Stationers at 1 Fore St Redruth. She was called Cordelia, I have found this most interesting and a brilliant read.

LikeLike