Reading time: 20 minutes

The Feast that the Rev. Chappell built…

Up to the mid-1800s – and the centuries before – a Cornish town’s annual Feast Day, held in honour of a Patron Saint, was regularly an excuse for a Rabelaisian fair of gluttony, boozing, sports and lechery. For example, in 1857 the well-oiled attendants of St Clement’s Feast in Truro partook of a game of hurling through the streets, which culminated in violence and vandalism over a disputed goal. The offending goal-scorer was later fired in effigy outside St Clement’s Church1.

Camborne’s Feast was no exception. It was nominally held in celebration of the life and works of St Martin of Tours, who, along with St Meriadoc, is commemorated in the local church of the same name. The Feast is traditionally held over the weekend nearest to November 11, ‘Martinmas’2, and previously encompassed

…great hospitality, and the fullest enjoyment…of the good things of life, and not paying much, if any, regard to the origin of the festival…

Cornish Post and Mining News, November 12 1921, p6

“Intemperance and disorder” were the main characteristics of the celebrations. On 1824’s Feast Monday, a “sporting” gentleman of Camborne accidentally (we are told) shot a local woman3. The man in question may well have been an enthusiastic (and/or intoxicated) member of the Four Burrow Hunt, who traditionally rode from the town centre over Martinmas weekend.

(Of course, nowadays a much-reduced ‘Feast’ is kept up by the Camborne Old Cornwall Society, and the Four Burrow Hunt still rides – legally or illegally, depending on which source you trust5.)

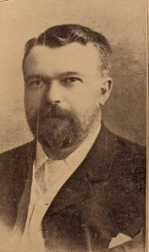

Camborne Feast’s glory years were in the late 1800s and the early 1900s, and this was due in the main to the efforts of the Rector of St Martin and Meriadoc’s, William Chappell (1829-1900).

Chappell sought to improve the reputation of his church, both visually and within the community. It’s due to the restoration work undertaken during his tenure (from 1860 until his death) that the building appears as it does today6.

Chappell was also a formidable cleric. He had to be, with the influence of Methodism and other nonconformist sects ever ready to shepherd away some of his flock. It was said of him that

…his church services grew on the affection of his people, and he was unremitting in visiting the sick and suffering…

Cornish Post and Mining News, November 12 1921, p6

But it was Chappell’s efforts to inject new spiritual vigour into Camborne’s Feast for which he is chiefly remembered. Year on year, church teas and suppers were provided, sermons digested, choirs applauded, and public lectures well attended.

In fact, so successful were Chappell’s innovations that Camborne’s Methodists, Wesleyans and Bible Christians of all stripes became involved. By 1880 posters advertised the Feast attractions well in advance, and townspeople, flushed with civic pride, whitewashed their houses in anticipation7.

The Feast took on a more orderly, Godly and teetotal manner. Nobody was reported as being drunk and disorderly over the Feast weekends in 1878 and 18828. A corrective sermon was delivered to the young in 1887 on the perils of “Gadding about”9, and the title of the public lecture in 1880, described as “interesting”, is worth quoting in full:

Reminiscences of a yachting tour in the Mediterranean…

West Briton, November 18 1880, p5

The Feast, in the jaundiced eyes of one commentator, was not being

…kept up the with best days of our forefathers…

Cornish Telegraph, November 16 1893, p8

But, fortunately, the old ways and customs died hard; indeed, in Camborne, they enjoyed an uneasy truce with the Feast’s new-found staidness. With the mines and factories in the area decreeing Feast Monday a half-day, there was still potential for, well, fun10.

In 1882 you could attempt to climb a greasy pole for a leg of mutton or race on a donkey. In 1883, you could gamble your pay on a wrestling match. In 1884 the ‘marrow-bone’ tradition (where a bone from a butcher’s is paraded about the town) was revived, and involved a good old-fashioned pub-crawl11.

Evidence of such activities may serve as a corrective to the notion that the Industrial Revolution, and rise of the fervently religious middle-class in 1800s Cornwall (the ‘protestant work ethic’) sounded the death-knell for many old games, sports and celebrations of the working classes12.

In any case, by the late 1870s, there was a new game in town. It vaguely resembled hurling, was easy to follow, and carried a frisson of violence.

The game? Rugby football.

Rugby pioneers…

Camborne’s pious middle-class had no option but to tolerate rugby football because, at this early stage of the sport’s incarnation, it was the almost exclusive preserve of well-heeled, muscular Christian young bucks. They were the kind of gentlemen who would nod thoughtfully at a Feast-weekend lecture with such a title as “Scriptural Holiness”, before retiring to a nearby field to beat seven bells out of each other in the name of character-building recreation13.

The historian and archivist David Thomas has highlighted the 1800s link between “mining, business and Methodism”14; to this we may add sport.

Elements in the Church of England and other Protestant denominations stressed the importance of exercise and recreation to

…refresh the strength and spirits after toil…both to the student and to those who were engaged in business…

Cornish Post and Mining News, October 27 1894, p415

Take, for example, Charles Vivian Thomas (1859-1941). The son of Josiah Thomas, staunch Methodist and manager of Dolcoath Mine, he was educated at Taunton Wesleyan College and Cambridge. In Camborne he set up practice as a lawyer, gaining a reputation as a firebreathing Wesleyan preacher along the way, coupled with a “magnificent physical development”16.

Thomas brought a sharp mind, a sharper tongue and a strong body home to Camborne. He also brought rugby football to the town, which he played while at Taunton Wesleyan College, where it was noted of him that he was

…a quick runner, a good scrag, and backs up well.

Wesleyan College Quarterly Magazine, 1877, p114. With thanks to Geoffrey Bisson, Queen’s College, Taunton

According to the Wesleyan’s records, Thomas returned home in the summer of 1877. He must have been desperate to continue playing rugby.

Fortunately for him (and for posterity), circumstances dictated that the time was now for rugby in Camborne. Redruth, after all, had formed their own club in 1875, so why shouldn’t Camborne have one?17

Camborne already had at least two cricket teams, Rosewarne and Roskear18, and the former club felt that, in the late summer of 1877,

…a football club [ought to] be formed in lieu of cricket…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, September 7 1877, p4

Charles W. Boot (1861-1938), a prominent member of the Rosewarne/Camborne Cricket Club, certainly agreed, and is often credited as the man responsible for forming Camborne RFC19.

Boot certainly had the right pedigree – indeed, those biographies I’ve traced of the town’s early footballers so far read like a Victorian Camborne’s Who’s Who. His uncle was William Bickford-Smith, his brother-in-law John R. Daniell, the lawyer. Boot’s wife, Florence, was the daughter of Wiliam Rabling, manager of Mexican silver mines, lumber merchant and Wesleyan kingpin20.

Boot himself was from Staffordshire, and an artisan smallware manufacturer. He was also a member of the Cornish Lodge of Freemasons, a Company Commander in the DCLI, and a Wesleyan preacher at Ponsanooth, who later promoted his faith in America21.

Boot had a team-mate who fancied chancing his arm (or breaking it) at rugby football: Josiah Rowe (1857-1932).

Rowe’s father was a mine-manager, and Josiah himself ran William Rabling’s lumber yard (where Camborne Bus Station is now located). Besides spending several years in South Africa and playing cricket and rugby, Rowe filled his spare time as Captain of Camborne Fire Brigade22.

James M. Holman (1857-1933) perhaps needs no introduction. MD of Holman Bros. from 1908 until his death, he was also a JP for Cornwall, a mining and banking director, as well as a governor of Camborne School of Mines23.

A Freemason like Boot, he must have also possessed some of Charles Thomas’s physical attributes in his youth. As part of Camborne’s 1879 Feast he was a ‘fox’ in a cross-country paper-chase, running 14 miles over rough ground in just over two hours24.

Thomas’s obituary in 1941 described him and Holman both as

…the pioneers of Rugby football in Cornwall…

Cornish Post and Mining News, January 18 1941, p3

In reality, Thomas, Holman, Rowe, Boot, and the eleven other men who made up Camborne’s first ever XV in 1877, were all pioneers25. Without them, Camborne RFC may not be celebrating the 150th year of its existence in 2027.

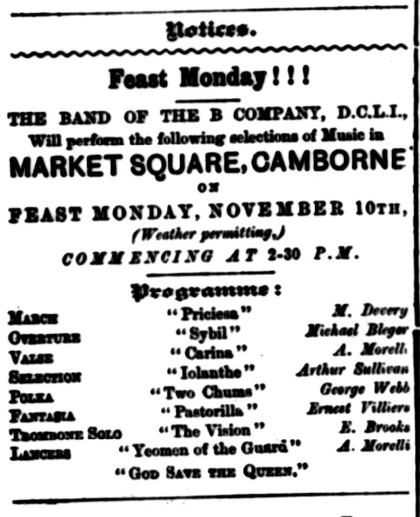

Feast Monday Rugby…

Camborne RFC’s first ever game was on Feast Monday, Martinmas itself, November 11, 1877. They played Penzance in a field let to them by Thomas Bath, owner of Higher Rosewarne Farm. Bath was not averse to hiring out his land; after all, Rosewarne CC were already established there, and he allowed a band to perform a concert on his property in 187926.

What’s more, in June 1877 Bath’s farm hosted the Annual Exhibition of the Royal Cornwall Agricultural Association, with a grandstand erected in one his pastures to hold a thousand spectators27. What better location for Camborne’s latest sporting venture? Indeed:

It being Feast-day, some hundreds of spectators were present; and at times became so enthusiastic that they could not restrain themselves from kicking the ball.

Cornish Telegraph, November 13 1877, p3

Camborne lost, by three tries to nil. Yet despite the defeat (and these rugby pioneers were playing for exercise, you understand; playing to win was seen as vulgar and demeaning to their station28), those who watched obviously enjoyed themselves, and Cornwall’s nascent sporting press made good copy from the event.

The Cornish Telegraph gave a list of both XVs, and a detailed report29. Meanwhile the Royal Cornwall Gazette salaciously listed

…two sprained ankles…stained handkerchiefs, scratches, bruises…

November 16 1877, p5

Rugby football was a hit. What the Rev. Chappell made of all these goings-on during his parish’s celebrations of the life of St Martin of Tours is unknown, but he can’t have minded all that much. Both Chappell’s sons played rugby for Camborne and by 1888, a club bearing the name ‘Camborne Church’ (which is local shorthand for St Martin and St Meriadoc’s) had been formed30.

All over Cornwall, rugby clubs were springing up like mushrooms31.

Large gates and annual customs…

Given the success of Camborne’s inaugural match, there are no reports of fixtures involving the club on Feast Monday until 1883, when they hosted a team simply known as ‘The Rovers’, and then again not until 1890 when Devon Albion visited32.

These gaps can be explained by recalling that fixture-arranging in this era was haphazard, and the reporting sporadic. Although the game had novelty value – a training session was worthy of an inch of column in 187933 – journalists would rather cover the religious aspects of the Feast, rather than the social. Rugby was played, as more clubs formed to accommodate a sport that had a broader class appeal than, putting it bluntly, a bunch of toffs hacking at each other for seemingly hours on end.

By the early 1890s, the Camborne XV already had a reputation as “burly miners”, and many local rivalries meant the gentlemanly notion of playing for playing’s sake (a modern coach might say, we’re not results-driven), had been forgotten34.

If Camborne didn’t play on Feast Monday, other teams in the town did. In 1895, Camborne Blues played Harlequins ‘A’ somewhere near Dolcoath Road, in a match of no real consequence other than the play being “very rough”35. We may rest assured that, if a match in these years is described as ‘very rough’, it must have been a borderline riot.

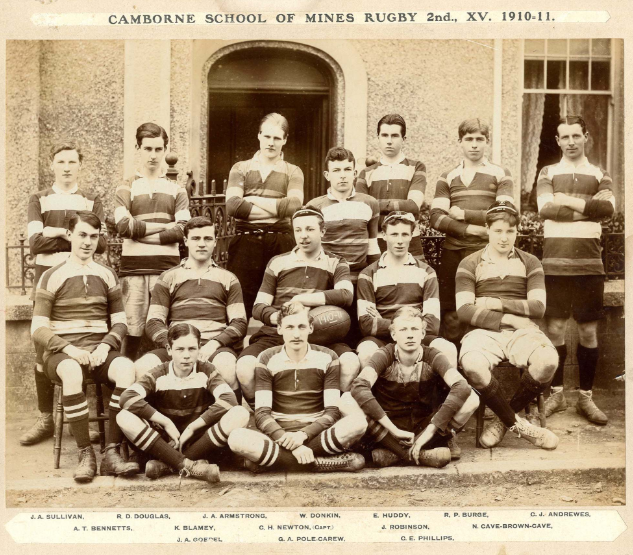

By the late 1890s, most Cornish newspapers ran columns dedicated to Association and Rugby football, naturally giving the game more coverage36. Camborne School of Mines RFC, formed in 189637, played four consecutive Feast Mondays against Redruth, and Camborne enjoyed parallel fixtures with Penzance or Newlyn38.

The CSM-Redruth fixtures were serious. The 1898 clash was “streets ahead” of the recent Cornwall fixture in terms of quality. The students approached it with great intensity; indeed

…they [were] practising hard every day…

Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 18 1898, p5

…for a fortnight before the match. Was this to be the great Feast Day rivalry?

No. Camborne, with their home now the Recreation Ground, first played Redruth on Feast Monday in 1900 (it was a scoreless draw39), but by 1908, of

…the many and varied attractions associated with Camborne Feast Monday, none can compare with the annual match between the local and Redruth Rugby Chiefs…

Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 12 1908, p10

(Redruth won, 14-8. Bert Solomon broke a collar-bone.)

This “annual custom”40 continued until 1919, and included some controversial wartime fixtures41. The crowds regularly rivalled that of Cornwall’s matches.

2,000 watched Redruth win in 1908; 4,000 saw Camborne win 8-6 in 190942. Fans wouldn’t just flock to the matches. Victorious ‘Town’ XVs would be lustily cheered in the streets by hundreds of well-wishers on their return to a Camborne hostelry to celebrate43.

In 1919, 4,000 saw Camborne win 6-3, and the club recorded its then biggest gate: £160 (£6,600 today). Its impossible, sadly, to calculate what the entrance fees were; women (regularly “a good many hundred”) had been allowed to spectate for free since 1903 at least, though it was chauvinistically observed that

…probably very few know anything of football…

West Briton, November 12 1903, p5

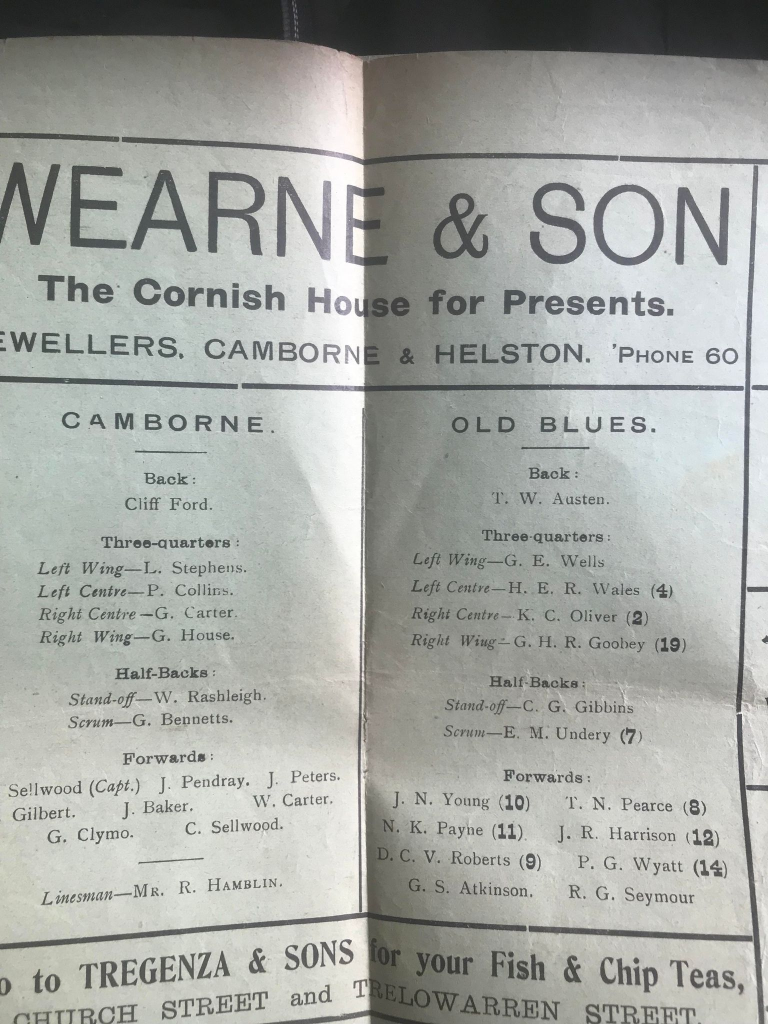

Even when a dispute with Redruth suspended their Feast Monday derbies in the early 1920s (more on that to follow next week), Camborne played Surrey’s Old Blues RFC on the date until the mid-1930s. There was no falling-off in interest: crowds still regularly topped 2,000, and the Blues could count on local support too. CSM students would bait their parent club mercilessly in the hope of an upset44.

The Old Blues were no fixture-padding also-rans. In a legendary era of Camborne rugby, with players such as Reg Parnell, Bill Biddick, Fred Rogers and Phil Collins (the father of John), the Blues “badly trounced” Town 31-5 in 192745.

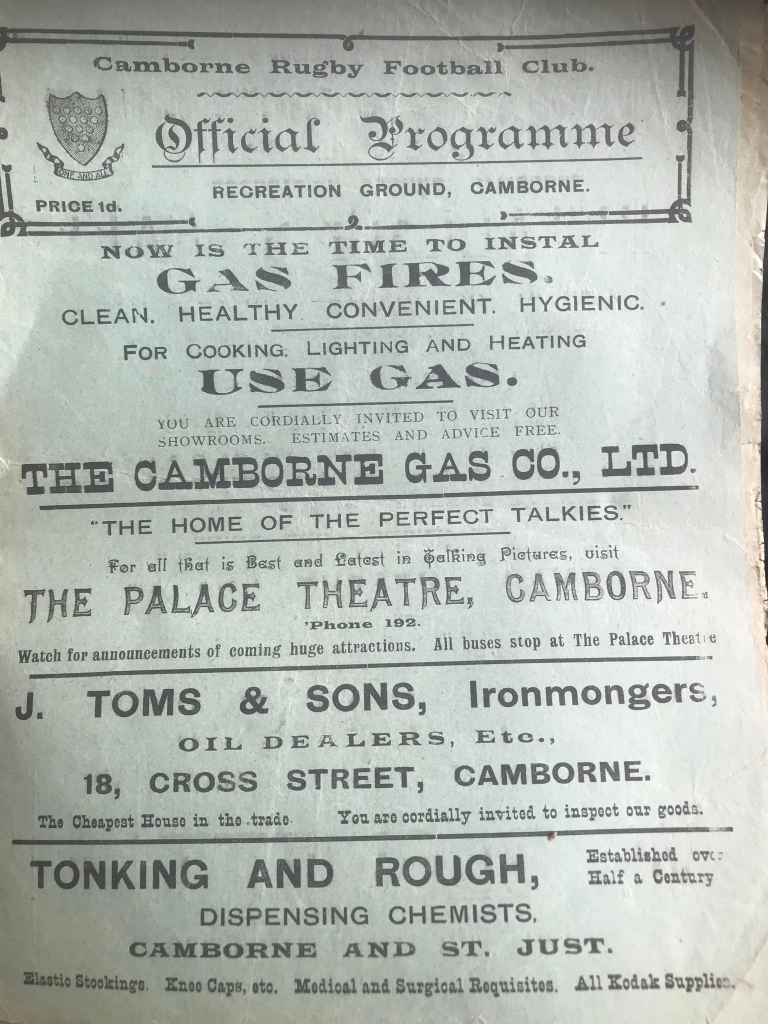

Feast hostilities with Redruth resumed in 1935. By 1937, Feast Monday was a half, or whole holiday for the entire town, schools included. The afternoon rugby match was the “great attraction”46. Camborne Town Band would lead the proud players from their changing quarters (Tyack’s, or Commercial Hotel) through the packed streets to the Recreation Ground, and perform for the masses at half-time, as in 194647.

Results would be the talk of both towns for days afterwards, such as in 1956 when Redruth humbled Camborne 41-348.

To state the obvious: Camborne’s Feast Monday fixture with Redruth was as big a game in Cornish rugby as the annual Boxing Day clash. The whole atmosphere of the occasion, with a holiday, hunt and livestock show showed that Camborne still knew how to do its Feast tradition proud, but above all it

…still has the same spirit in its Feast Monday football…

Cornishman, November 16 1950, p5

But the last game was played in 1963, and the writing had been on the wall since 1962. That year, Holmans had remained open (and would remain so) on Feast Monday, offering their thousands of employees (many of whom played, or followed rugby) an extra day’s holiday at Christmas. Other businesses followed suit, and quickly it became apparent that a Feast Monday rugby match would be a non-event, in terms of both fans and players.

Despite complaints as early as 1964 that, mainly due to the loss of the rugby, the Feast “isn’t what it used to be”, a great Cornish sporting tradition had definitively come to an end50.

A Holman gave birth to a club, and a tradition. The works that were his family’s legacy ironically ended that tradition. The Industrial Revolution had belatedly caught up with the Camborne Feast.

From 1877 to 1963, Camborne RFC had played over sixty Feast Monday matches.

With no competition, the Camborne-Redruth Boxing Day derby (held solely in Redruth from 1935 to 1963), rapidly increased in importance. Nowadays, it is believed to be the oldest continual rugby fixture in the world.

But is it? Find out by clicking here…

Many thanks for reading. Follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

References

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, November 27 1857, p5. For more on Cornwall’s Feast Days, see Cornish Feasts and Folklore, by Margaret Courtney, 1890. See my article on effigy burning in 1800s Cornwall here: https://cornishstory.com/2022/07/02/effigy-burning-in-nineteenth-century-cornwall/

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Martin’s_Day

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, November 20 1824, p2. The ‘intemperate’ nature of the Feast in days past is recalled in the Cornishman, November 18 1886, p5.

- From: https://www.cornishmemory.com/item/BRA_18_171

- David Thomas, Archivist at Kresen Kernow, assures me the Feast will go ahead this year. For dates, see: https://kernowgoth.org/member-societies/camborne-old-cornwall-society/. Four Burrow Hunt was still going strong – and killing animals – in the 1990s: see the West Briton, November 16 1995, p20. Follow these links for more on its post-ban activity: https://www.wildlifeguardian.co.uk/hunts/four-burrow-hunt/, https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/cornwall-hunt-accused-putting-dogs-8124091, and the Hunt’s own Facebook page.

- See: https://cambornecluster.org.uk/camborne-church/history/, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Martin_and_St_Meriadoc’s_Church,_Camborne

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, November 12 1880, p8. See the Cornish Post and Mining News, November 12 1921, p6, for more on the involvement of other religious groups, and Chappell’s obituary in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, February 8 1900, p7. On Victorian civic pride, see Asa Briggs, Victorian Cities, Penguin, 1968.

- As remarked in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, November 15 1878, p5, and the Cornish Telegraph, November 16 1882, p5.

- Cornish Telegraph, November 17 1887, p8.

- The local half-day is mentioned in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, November 15 1878, p5.

- Cornish Telegraph, November 16 1882, p5; Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 16 1883, p7; Cornishman, November 20 1884, p7. The ‘marrow-bone’ tradition is also mentioned in Margaret Courtney’s Cornish Feasts and Folklore, 1890, p10.

- A. K. Hamilton Jenkin makes this assertion in The Cornish Miner, 3rd ed., George, Allen & Unwin, 1962, p124. See Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the ‘Spirit’ of Capitalism, Penguin Classics, 2002.

- “Scriptural Holiness” was the lecture on offer at the 1888 Feast; from the Cornish Telegraph of November 15 that year, p5. Tony Collins has traced the middle- and upper-class origins of rugby (and how it supplanted the more plebeian hurling) in Rugby’s Great Split: Class, Culture, and the Origins of Rugby League Football, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2006.

- From: https://cornishstory.com/2022/03/25/mapping-methodism-beacon-wesleyan-chapel/

- The quote is taken from a debate on the necessity of sport by the Camborne Wesley Guild. It may not surprise you that Charles Vivian Thomas was present.

- As gleaned from the 1881 census, the Cornish Telegraph, August 25 1875, p3, and Thomas’s obituaries in the Cornishman, February 20 1941, p6, and the Cornish Post and Mining News, January 18 1941, p3, where the “physical development” quote is taken. He gave a notably “fiery” sermon on the alleged folly of ritualism, as noted in the Cornishman of November 24 1898, p7.

- Nick Serpell, Redruth RFC’s historian, and myself have searched in vain for the source of the following quote in Tom Salmon’s The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall (CRFU, 1983, p41) on the origins of Camborne RFC: “After all, Redruth have got one”. Alas, the quote may be apocryphal, but the sentiment probably wasn’t.

- The two clubs played each other regularly, for example see the Royal Cornwall Gazette, June 29 1872, p5.

- Noted in the Cornishman, January 5 1961.

- See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Bickford-Smith, and https://cornishstory.com/2022/03/25/mapping-methodism-beacon-wesleyan-chapel/ for information on William Rabling. For Boot’s connections see the obituary of his grandmother in the West Briton, March 11 1886, p4, Florence’s obituaries in the Cornishman, July 27 1941, p8, the West Briton, July 27 1941, p5, and the 1881 census.

- Taken from: the 1881 and 1891 census, the United Grand Lodge of England Freemason Membership Registers, 1751-1921 (Ancestry), Royal Cornwall Gazette, August 28 1890, p6, and Florence Boot’s obituaries (above).

- See Rowe’s obituary in the Cornish Post and Mining News, October 22 1932, p5, and him in the action for the fire brigade in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 27 1894, p4. David Thomas notes the location of Rabling’s yard here: https://cornishstory.com/2022/03/25/mapping-methodism-beacon-wesleyan-chapel/

- From Holman’s obituary in the Cornish Post and Mining News, March 4 1933, p4.

- Cornish Telegraph, November 12 1879, p5. Evidence of his freemasonry can be found at: United Grand Lodge of England Freemason Membership Registers, 1751-1921 (Ancestry).

- The team was named in the Cornish Telegraph, November 13 1877, p3. Early rugby matches, in fact, regularly featured sides of twenty players.

- See the 1881 census for information on Thomas Bath. Camborne’s game is reported in the Cornish Telegraph, November 13 1877, p3, and the Royal Cornwall Gazette, November 16 1877, p5. The Gazette has them actually playing on the cricket pitch. The concert on Bath’s farm is reported in the Cornishman, June 5 1879, p5. It wasn’t until the 1898-99 season that Camborne started playing at the Recreation Ground: see the Cornishman, September 22 1898, p2.

- From the Cornish Telegraph, June 12 1877, p3.

- See Tony Collins’ Rugby’s Great Split: Class, Culture, and the Origins of Rugby League Football, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2006, for more on the amateur ethos of early rugby.

- November 13 1877, p3.

- In September 1888, Camborne RFC was actually forced to wind up its affairs and fold: a debt of just over £2 (£213 today) is cited as the cause. Into this rugby vacuum the Camborne Church club was formed a month later; doubtless it contained many names from its previous incarnation. By late November, though, Camborne RFC had reformed at the Golden Lion pub; Camborne Church was still fielding a team in 1907. Hence, there was no Feast Monday game in 1888. See: Cornish Telegraph, September 27 1888, p5 and October 11 1888, p5; Cornish Echo, October 13 1888, p6; Western Morning News, November 23 1888, p6. The Rev. Chappell’s sons playing for Camborne is mentioned in the Camborne RFC Centenary Programme 1878-1978, by Philip Rule and Alan Thomas, 1977.

- As documented in Tom Salmon’s The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall, CRFU, 1983.

- The Rovers beat Camborne; no score is recorded for the Albion match. From the Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 16 1883, p7; and the Cornish Telegraph, November 16 1890, p5.

- The Cornish Telegraph noted the Camborne side were playing “by moonlight”: obviously, this was an evening workout. December 3, 1879, p5.

- The Camborne side were described as such in the Cornishman, November 24 1892, p10.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, November 15 1895, p5.

- For example: Cornish Post and Mining News, December 14 1899, p2; Cornishman, November 9 1899, p2.

- As documented in Tom Salmon’s The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall, CRFU, 1983, p95-6.

- For the CSM matches, see: Cornishman, November 12 1896, p5; West Briton, November 4 1897, p11; Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 18 1898, p5; Cornishman, November 23 1899, p3. For the Camborne matches, see: Cornishman, November 24 1898, p7; Cornishman, November 23 1899, p3.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, November 15 1900, p3. Camborne had been playing at the Rec since the 1898-99 season: see note 26.

- Cornish Telegraph, November 16 1905, p5.

- Although the CRFU had stopped play by November 1914, that year’s Feast derby went ahead, and came in for criticism: why aren’t these healthy young men at the Front? That said, all takings were donated to a patriotic fund. See: West Briton, November 30 1914, p2; Cornish Telegraph, October 22 1914, p2. Ironically, soldiers on leave enjoyed the 1915 derby, and the 1916 edition (against Plymouth) drew a large collection for the Royal Naval Hospital, Truro. See: West Briton, November 18 1915 p6; and November 16 1916, p8. Only two games were played on Feast Monday in World War Two: in 1944, the Camborne Home Guard played RNE Devonport, and lost. In 1945, Camborne beat Redruth 6-5. See: Cornishman, November 16 1944, p6; and November 15 1945, p6.

- Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 12 1908, p10; and November 18 1909, p10.

- As observed in the Cornubian and Redruth Times, November 17 1910, p5.

- From the Cornish Post and Mining News, November 14 1925, p8.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, November 19 1927, p6. In the scoring system of the time, a try was three points, but a converted try was 5 points, with the original try not to be added to the total. The Blues put five goals and two tries past Camborne. Converting a three-point try to a five-point goal was known as “majorised”: West Briton, November 15 1906, p3-5.

- West Briton, November 18 1937, p8.

- West Briton, November 14 1946, p7. The Camborne XV’s musical guard of honour for home fixtures is mentioned in the Camborne RFC Centenary Programme 1878-1978, by Philip Rule and Alan Thomas, 1977.

- West Briton, November 15 1956, p2.

- See: http://cornishstory.com/2021/02/10/holman-echoes-of-an-age/

- See: West Briton, November 15 1962, p9; November 14 1963, p5; November 19 1964, p6.

Bloody good read as always Francis. RoyJennings

LikeLike

Sutch

information

LikeLike

Francis gre

LikeLike

Cheers Frank!

LikeLike

Very interesting again Francis. So well written and researched. Enjoyable read

LikeLike

Cheers Alan

LikeLike