Reading time: 30 minutes

(A version of this post was presented as a speech at the 100th Anniversary Celebrations of the Cornwall ~ All Blacks match at Camborne RFC on September 20, 2024)

It’s just after lunchtime on Wednesday, September 17, 1924. Camborne is a ferment of expectation. Over the past few years, the town hasn’t had much to look forward to, but today is different.

Today, any minute, special guests are arriving.

Tomorrow, Thursday the 18th, a special game will be played.

Camborne will be hosting the Cornish rugby team – and their opponents.

Camborne’s people know how to welcome visitors. Even when their arch-rivals, Redruth, come to play at the Recreation Ground for the annual Feast Monday fixture, houses and fences would be whitewashed anew. Camborne Town Band would march ahead of the XVs from the town centre to the pitch, and folks would line the streets to cheer on (or hurl insults at) the iron-jawed, muscled players1.

Today, even the Town Hall is decked out in flags and ferns. Today, even the grandees of the Cornwall RFU are here, in their very best Sunday best. They’re currently up at Camborne Railway Station, pacing the platform with equally starch-shirted members of various town councils, straightening their ties and checking their pocket-watches2.

Everything, and everyone, had to be ready.

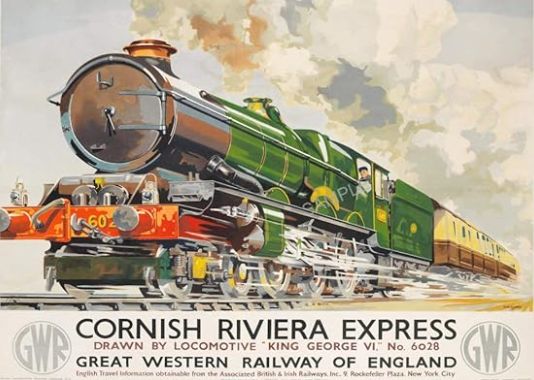

For the first time in several years, Camborne was the centre of attention – for all the right reasons. Great Western Railways were attempting to cash in on the town’s new status as a visitor hotspot by offering cheap excursion trips3. Camborne’s hoteliers and businessmen were rubbing their hands with glee.

It seemed every entrepreneur and raconteur wanted to get in on the act. Hell, there was probably even some wild rumour going about the place regarding an aeroplane display tomorrow?! But no, surely that was crazy talk.

Yes, Camborne needed something positive to get behind. For in Camborne in 1924, it was hard times. Holmans may have been employing over 500 men, Roskear Mine may have looked promising, but Camborne was no longer the epicentre of a Cornish mining industry that had once dominated world trade4.

Prayers had been offered in the churches for God to intervene and save Camborne’s mines, but God wasn’t listening6. Nor was the Government. A loan of £200,000 (that’s £7.5 million today) was requested to keep Wheals Dolcoath and Grenville open. The miners themselves sent petitions, but to no avail7.

The price of tin was too low, the price of coal too high, developmental work was impossible, and machinery was out of date. Dolcoath hadn’t paid dividends since 19138.

As the miners were laid off by the hundred, their fatalism was apparent:

I have tramped this road daily for more than thirty years, and now I am doing it for the last time…God knows whether I shall have dinner next Sunday…

Cornishman, June 30 1920, p5

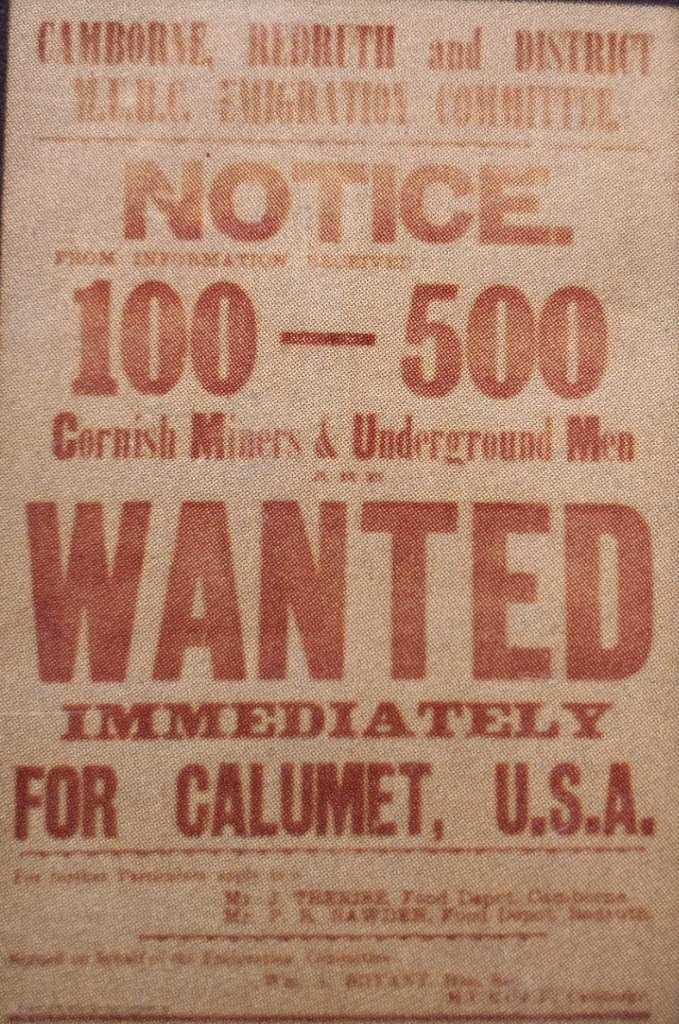

By 1921, there were 3,000 unemployed miners in Cornwall. By 1924, Camborne had the highest Cornish unemployment rate. Burial rates for nearly a thousand people had been excused. Since 1922, the Camborne Relief Fund had distributed £75K, or £2.8 million in 20249.

In desperation, the ex-miners formed charity choirs, and must have cut a pathetic sight on the streets, or at half-time during rugby matches10.

Others simply left. In 1920 a hundred Dolcoath men sailed for Ontario, with another hundred to follow11. Others, such as Camborne RFC’s Ernie ‘Tatsy’ Wills, backed their sporting abilities and joined the Northern Union. In 1922 he signed to Rochdale Hornets for £350 – that’s £16K now. Not bad for a man who, in 1921, was just another unemployed miner. He wasn’t the first, and he wouldn’t be the last12.

By January 1924 Camborne’s unemployment figures revealed an astounding fact:

…it seems that all the miners have gone.

Cornish Post and Mining News, January 19 1924, p5

Some had gone to seek a better life in New Zealand14, and it is here that we begin to understand why Camborne’s townspeople had so extravagantly pushed the boat of welcome out.

Camborne was hosting a County rugby match, yes, but this was bigger.

For, on Thursday 18th, 1924, Cornwall’s opponents would be New Zealand – The All Blacks.

And the people of Camborne wanted to say thank you. When the train finally pulled in that afternoon (proving once and for all that the train does indeed stop at Camborne on a Wednesday), the tourists were addressed by the Chair of Camborne’s Unemployment Committee:

…our fathers and grandfathers emigrated to the dominions, and wherever there is mining you will find Cornishmen…During the time of the mining depression New Zealand assisted us and many of our young men went to your country to work…

Cornish Post and Mining News, September 20 1924, p4

From the Copper crash of the 1870s (which has traditionally marked the beginning of the end for Cornish mining), over 5000 Cornish emigrants travelled to New Zealand. This number swelled through the early 1900s, creating a ‘dependency culture’ in Cornwall: the wages sent home from countries such as New Zealand put bread on the table in the former mining districts16.

Things may have been bordering on the desperate in Camborne, but the money earned and the support given from New Zealand had truly kept the wolves from the door.

And Camborne wanted to show its gratitude. New Zealand, represented that day in 1924 by its rugby team, was a symbol of hope, of better times.

The people of Camborne had another reason to celebrate too, and be at the game en masse.

Seven of the Cornwall XV to line up against the All Blacks were Camborne players. An eighth, scrum-half Albert Gibson, was a Hayle player but had guested on occasion for Camborne the previous season17.

And when I say they were Camborne players, they were Camborne men too. They worked at Holmans, or Climax, or were miners – if they could find a mine that wasn’t a scat bal, as they used to say. They were ordinary men, working men, who had given up a day’s pay (that they could scarcely afford to sacrifice), to represent Cornwall and face down the mightiest rugby team on the planet.

If we’re being uncharitable, we could say that, in picking seven Camborne men for a game at Camborne the Cornwall RFU were ensuring plenty of local bums on seats. However, the CRFU’s selection committee were from Redruth, Hayle and Falmouth, and would have doubtless pressed the merits of their own players18.

For Camborne was easily the strongest club in Cornwall. Though earlier that year they had lost the services of their skipper, County centre Leonard Hammer, to Birmingham19, the 1923-4 season ended with 32 wins from 49 matches, and 3 draws. 605 points had been amassed, and 305 conceded20.

That season, they were undefeated against Redruth. In fact, they beat Redruth a record five times21. Their play overall was noted as “splendid”, but Town were also the meanest, most “brutal” XV on the block22.

In one victory against Redruth, Reds’ skipper Ray Jennings was booted unconscious after taking a penalty. In that same match, three other Redruth players were knocked out and spectators had begun to ask why the perpetrators weren’t arrested23.

Even by the standards of the day, Camborne were hard.

So, who were The Magnificent Seven?

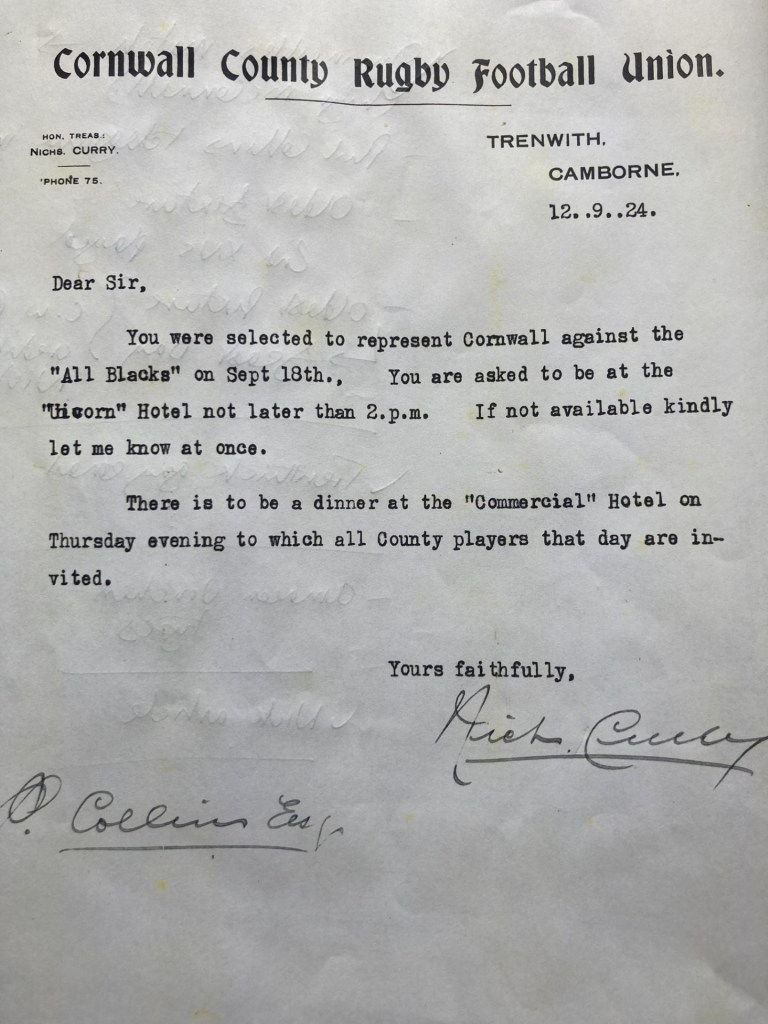

Phil Collins (1905-1964) was the kind of centre you did not want to be tackled by. A 5ft 9, 12 stone rock-drill engineer at Climax, the stocky lad was picked for Cornwall at the tender age of 17, and was only 19 when he faced New Zealand – or rather, they faced him. He earned over forty caps for his County, and was their skipper in three separate seasons (1925-6, 1928-9, 1930-1).

Such a strong, fast tyro was always going to attract the attention of bigger clubs, and so it proved. Phil guested for the powerful Plymouth Albion XV in 1923; family tradition has it they ‘looked after’ him financially.

In 1922 the Northern Union club Leeds had come knocking. Phil was offered £600 down to sign (that’s £28K today), £4 (£190) per match, and a job at a local engineering firm. For one reason and another, he turned them down. Likewise Oldham, who approached him twice.

On his retirement in 1934 he was described as

…one of Camborne’s great footballers.

Cornishman, November 29 1934, p9

Of course, his other claim to fame is as the father of the only Camborne player (to date) who has represented England, John Collins. One of John’s earliest memories of his dad is watching him play for Camborne at Plymouth Albion. So aggressive was Phil, and so devastating his tackles, that he endured no end of stick from the home crowd. Apparently, this wasn’t uncommon. Such was his speed that a 3-versus-2 overlap could be negated by him making two tackles himself.

Cornwall were going to need all of him in 192425.

Collins’ centre partner was to be Fred Barnard (1895-1976). Of the seven Camborne men who played the All Blacks, Fred’s story best illustrates how tough life in Camborne could be at the time.

When Fred was six, his father (aged 35) and eldest brother (12) both died from lung disease. As soon as they were able, Fred and his five siblings had to find work, with their widowed mother scratching a living from charring. In 1921, he was out of work – in Camborne surface labourers for the mines were a dying breed. Poverty and destitution were a constant threat.

Fred must have been a tough, cussed character. In 1923 he quit Camborne RFC when he wasn’t selected for the inaugural Crawshay’s fixture, and then did the unthinkable in joining Redruth. (In those days, such an act was liable to get your windows smashed and you barred from all of Camborne’s pubs.) He saw the light, however, and returned to the fold for the start of the 1924-5 season.

He didn’t know it yet, but this game was to be the last of his three caps for Cornwall – but what a fixture to go out on26.

Half-back Rafie Hamblin (1904-1990) was a genuine Camborne character. For many years he ran the family butcher shop on Trelowarren Street, and was a regular at the old clubhouse on East Terrace, dispensing sage advice to youngsters. His son, Paul, who also came to be known as ‘Rafie’, proved an equally fine servant to the club.

As a player, Rafie must have been sharp, quick and alert. Not the biggest man on the pitch, he was elected skipper for the 1927-8 season, at a time when the Camborne side of the Roaring Twenties were at the peak of their powers. This was a period when Town could best the ‘Welsh Barbarians’, Crawshays, and do a number on Bath.

Rafie had other interests besides rugby, including exhibiting his prize cockerels and racing a 500cc BSA on grass tracks. He once assisted in saving a man from drowning at Kynance Cove. He was also renowned for the dark red hue of the tomatoes he grew and sold; unbeknownst to his customers, the colour was achieved by liberal applications of pigs’ blood to the plants’ soil.

Nevertheless, one of Rafie’s proudest moments was the day he played the All Blacks, and he would often recall it as the biggest of gates, and the friendliest of matches27.

Though hailing from Wadebridge, forward Bill Biddick (1896-1984) is a Camborne RFC legend. Another Holmans/Climax man, while apprenticed during WW1 he joined the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (1/5th Battalion), and probably saw action on the Western Front.

He played his first rugby for Beacon, and was associated with the village’s cricket team for many years. However, Town soon secured his services – as did Cornwall. He was a master of the line-out, and by all accounts possessed a massive punt.

Inevitably, Biddick’s prowess and physical presence on the pitch rapidly attracted the interest of the Northern Union clubs, and Rochdale Hornets offered him £100 (nearly £5K today) to join them in 1922. With a steady job at Holmans, he could afford to turn them down.

Equally inevitably, Biddick became Camborne’s skipper, and led them during their most successful season, 1926-7: played 38, won 32, drew 2; points for, 651; against, only 151. As we saw earlier, during the 1924-5 season they scored over 600 points yet conceded over 300: this time round, Town were a much tighter unit.

As Bill himself remarked,

Camborne were on top in those days, and no matter where we played they were all after our blood because we were the tops.

Camborne RFC Centenary Programme, 1878-1978

Those who knew him would know this was no idle boast. All the people I spoke to, including his son Derek who, along with brother Max, also played for Camborne, recall him as a modest, distinguished gentleman, who would make a point of not bragging about his achievements.

Indeed, the only time he would truly open his mouth was to sing, as he regularly did in a choir at the Carnhell Green pub on a Sunday evening.

Humble or not, Bill could have bragged plenty. When Cornwall beat Middlesex in the County Championship semi-final of 1928 (they lost to Yorkshire in the final), Biddick’s performance was singled out for being truly monstrous. When you consider that his opposite number that day was the England Captain (and no shrinking violet himself) Wavell Wakefield, you begin to understand how good Bill Biddick was, and how unlucky to never gain international recognition.

Remembered as

…a giant in every respect…

West Briton, January 5 1984, p6

…in 1924 he could show the All Blacks what he was made of28.

Wing-forward Walter Mayne (1903-1981) was a rugby pioneer. A fitness fanatic who could sprint up Camborne Hill, in 1921 he was an 18 year-old miner and out of work. Like Fred Barnard’s, Walter’s dad had died of lung disease, leaving him the family’s sole breadwinner.

When he eventually found work, it didn’t suit Walter – perhaps understandably. His job underground was to wade through deep water and clear the mine’s drainage channels, so when opportunity knocked, he took it.

Walter emigrated to Chicago in 1926, taking a job at Crane Co., a valve engineering firm. During WW2 his department was unknowingly part of the Manhattan Project, and Walter went on to work at several nuclear power plants and submarines, such as USS Nautilus.

Such were Walter’s services to the Atom in the States that he once met President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

More importantly for us, Walter brought rugby union to Chicago, forming the Chicago Southerns club in the 1920s.

Along with Penryn’s George Jago (who played with Walter against the 1924 All Blacks), Walter deserves recognition as a forgotten trailblazer of rugby union in America. Once a game confined to colleges, nearly a hundred years later the USA’s Major League boasts 13 professional clubs.

Walter Mayne went a long way, but he never forgot where he came from. In 1972 he visited Camborne (and his elderly mother in Beacon), receiving a hero’s welcome from old friends and team-mates.

Naturally, he watched his old team, and said of them that

…they are just as good as ever we were. They have the speed and the courage and the will to play good football…I say to Camborne folk, ‘Get down there and give the Camborne lads some support. They deserve it’.

Qtd in: Henry Cecil Blackwell, From a Dark Stream: The Story of Cornwall’s Amazing People and Their Impact on the World, Truran, 1986, p220

Back in 1924, they were coming through the gates in their thousands29.

In the amateur game, working men had to accept that work came before play, and that where you worked, or where you came from, might hinder the progression of your play.

Witness the story of Herbert Wakeham (1897-1963), who has a reputation of being one of Camborne’s toughest ever forwards, and also the unluckiest. As a drill salesman for Climax, his frequent and far-from brief journeys abroad counted against a fully realised rugby career.

A WW1 Warrant Officer in the DCLI (he was stationed at St Antony), Herbert played all three England trial matches during the 1920-1 season, yet missed out on selection.

In the final match, he was the only player representing a Cornish club, trying to prove his worth against servicemen, University dons and gentlemen of the Home Counties. One suspects his face didn’t fit.

At this time he was also offered a Northern Union contract, but in late 1921 Climax sent him to South Africa; he only returned in 1924. Luckily for Herbert, he was able to keep his rugby hand in by playing for Transvaal’s Pirates RFC.

Rushed into the Cornwall XV for the All Blacks fixture, he was also selected for another international trial. Again, full honours eluded him.

In 1927 Herbert sailed once more, this time for Malaya. Camborne RFC presented him with a silver tea service (now a precious family heirloom), and it was said of him that he was

…undoubtedly a tower of strength to the side…an inspiration to any team…[who] always played a clean and sporting game.

Cornish Post and Mining News, January 1 1927, p2

(That said, Herbert was one of three men sent off – and later suspended – for fighting during the notorious 1926 Camborne-Redruth match that led to fixtures being abandoned between the clubs for two years. In his defence, he seems to have retaliated.)

He wouldn’t return home until the mid-1930s, by which time, sadly, he was past his peak. A serious dose of malaria contracted whilst abroad can’t have helped.

Like Bill Biddick, Herbert was a big, strong, tough man. In September 1924, he would be relishing the challenge of playing against the best30.

Herbert’s greatest pal was George Thomas (1895-1971). They both joined the DCLI’s Territorials in 1914, and people who knew them said that

…they were very keen and friendly rivals for promotion during the war and for county rugby honours afterwards.

Cornish Post and Mining News, September 9 1933, p6

Wakeham achieved the higher military rank and greater rugby recognition. George, no slouch, rose to be Sergeant Major himself, and won eleven caps for Cornwall. Of similar build to Phil Collins (5ft 10, 12st 7), he gained something in the war that Herbert didn’t: George was wounded in France, and hospitalised near St Quentin.

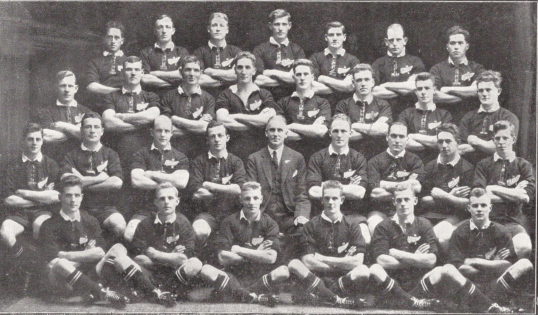

Fortunately, his injuries can’t have been serious, and he was back playing for Camborne – alongside Herbert – for the 1919-20 season. By 1924, he was Town’s Captain, which tells us that George was, with his military experience, a good leader of men. That 1924-5 XV is, by common consent, the finest Camborne side ever assembled: thirteen of the players pictured (above) represented Cornwall; if Rafie Hamblin hadn’t been injured and absent from the photo, the number would have been fourteen.

On his retirement in around 1933 (and George had a long career, making his Camborne debut in 1912 aged 17), he became the side’s trainer. Being a PT instructor in the Army doubtless helped, and his love of Swedish Drill and physical jerks whipped the Town boys into shape throughout the 1930s.

(That Camborne had a gym instructor as early as 1919, a role George was to occupy later, serves as a corrective to the notion that coaching and training are relatively modern phenomena. In the amateur era, Camborne’s methods were bordering on the professional. Small wonder they dominated the 1920s.)

Clearly not a man to be taken lightly, George was also something of an entertainer. His banjo playing made him a valued member of a local black-and-white minstrel band, such forms of entertainment being popular at the time.

One imagines that, for the All Blacks, George certainly had his game face on31.

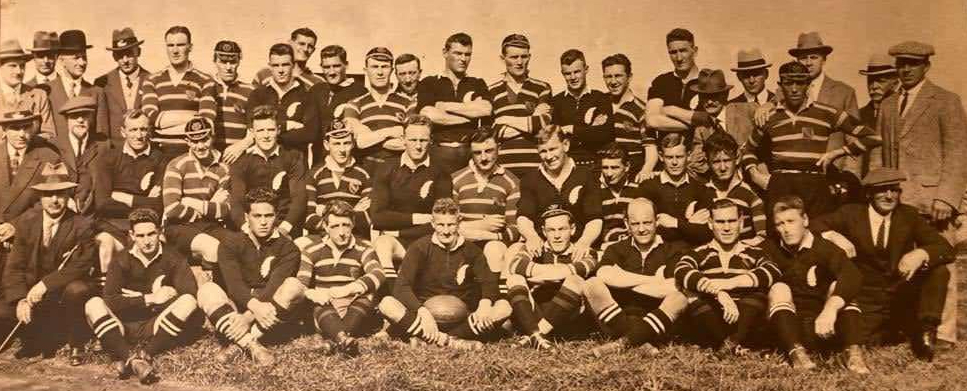

The New Zealanders had their frivolous side too. Rafie Hamblin would recall how, when the following photograph of the two XVs was taken, there was so much fooling about the lensman finally lost his rag. Certainly, they all look happy to be there.

But that wasn’t all the tomfoolery on display. Shortly before kickoff, the 12,000 crowd crammed cheek by jowl in temporary (and permanent) grandstands were treated to a breathtaking aerobatic display by WW1 Ace Captain Percival Phillips, DFC, of the Cornwall Aviation Company.

Phillips’ Avro 504 biplane swooped low over the trees, looped the loop and bombarded the pitch with leaflets advertising cheap joyflights, while the punters gasped in awe.

It later transpired that neither the Cornwall RFU or Camborne RFC had hired, or indeed given Phillips permission to indulge in his little sortie. Hauled before Camborne magistrates’ court, accused (amongst other things) of dangerous flying, Phillips confessed that the only people to consent to his buzzing the Recreation Ground…were the All Blacks themselves34.

But it was about to get serious. Camborne Town Band had run through ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. The crowd, thousands of them, had naturally belted out ‘Trelawny’. The National Anthems had been sung. The All Blacks had treated the crowd to what was described as

…their weird war cry…

Cornish Post and Mining News, September 20 1924, p4

Finally, everyone was about to see what the All Blacks were about.

For it was the rugby people had paid their money for. The tourists were supposed to be the best. The sport historian Lynn McConnell has written that

New Zealand’s sporting success demands that no ground be conceded in the ever improving quest for excellence and staying a step or two ahead of rival nations.

Lynn McConnell, Will the NZ Government be a Party Pooper?37

The All Blacks’ Tour Manager in 1924, Stanley Dean, went further:

Rugby is almost a religion in our country.

Cornubian and Redruth Times, September 25 1924, p6

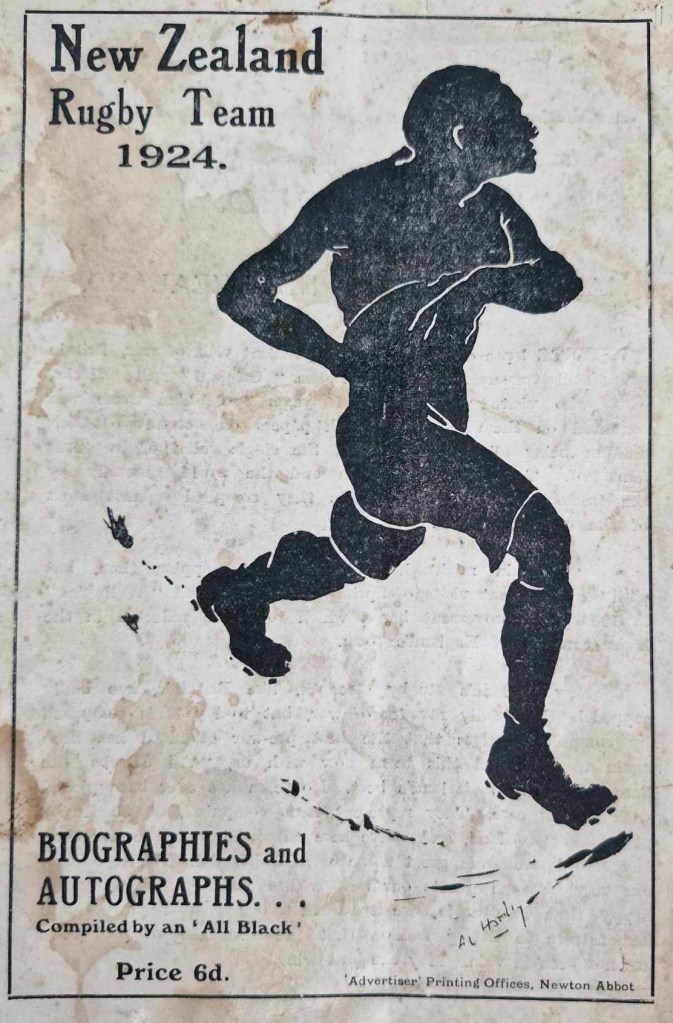

New Zealand’s players had a reputation to uphold. The previous visitors to the British Isles in 1905, known as ‘The Originals’, had only lost one match, against Wales. They had slaughtered the English XV and made each and every one of their opponents look lumpen and outmoded.

Indeed, before The Originals lost to Wales, the press were in fact calling them The Invincibles38.

The Originals had played the legendary John Jackett’s Cornwall XV too, and beaten them easily. (One Cornish great from that era, Redruth’s international half-back James ‘Maffer’ Davey, was at the match in 192439.)

Could this New Zealand party go one better than The Originals, and beat everyone? Could Cornwall upstage their 1905 counterparts and pull off a shock victory?

Few at the time thought Cornwall had it in them40, but there was a feeling that these tourists were not of the same calibre as the 1905 vintage. Nobody was calling them ‘The Invincibles’ yet (obviously), and in their opening match, Devon had run them surprisingly close41.

Before the All Blacks had sailed for Britain, Auckland had beaten them in a warm-up match, leading one Original to say that this was

The weakest team New Zealand has ever had; weak in scrums, weak in defence, and lacking in pace…

From Lynn McConnell, All hell breaks loose after Auckland loss43

Even a concerned New Zealand Government had intervened in the tour’s selections. They had a full-back, George Nepia, who looked out of position, and a captain, Cliff Porter, who had no idea why he’d been elected44.

However, this was a touring party selected after nine trial matches. This was a touring party who had gelled as a XV in a series of warm-up matches in Australia. This was a touring party who, in their month or so at sea, barring the Sabbath trained every morning from 6:45am till noon. This was a touring party who, reckoning they’d soon be meeting some of the players in person, watched Camborne beat Torquay in Devon, and doubtless made mental notes45.

Once arrived, they practised daily at Newton Abbot, and were rapidly getting admiring murmurs from the press. Their impressive, if not imposing vital stats were recorded, as were the

…exceptionally clever exhibitions of the short passing game…[they] are one of the fastest teams ever sent over, and they are also great tacticians.

Cornishman, September 10 1924, p6

Compare this to Cornwall’s preparation. The final XV was picked from one trial match47, and, as Phil Collins’ notice of selection makes clear, there was to be no further warm-ups or training:

In the previous season’s County Championship, Cornwall had lost all three matches, and were described as the “weakest” XV in England48.

After the All Blacks ran in three tries in the opening ten minutes (the final scoreline was 29-0), victory was a foregone conclusion. They were just too good and, like the thousands fortunate enough to see them play at Camborne that day, Cornwall’s players could do little else but admire them49.

Cornwall’s big, heavy forwards weren’t big and heavy enough. The All Blacks shoved them off the ball and, indeed, all over the pitch. In a game that featured no less than fifty-five scrums, the visitors had ample opportunity to assert themselves. Always unlucky, late in the game Herbert Wakeham had to come off injured. Biddick, Mayne and Thomas were all hard men, but Maurice Brownlie (6ft), Ian Harvey (6ft 1), and Les Cupples (6ft 2) were something else.

England skipper Wavell Wakefield would later say of Brownlie that attempting to tackle him when on the rampage was like trying to fell

…a moving tree-trunk…

Qtd in the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame

Phil Collins, as you would expect, tackled like a demon, but he and Fred Barnard struggled to attack from the centre. Bert Cooke and ‘Snowy’ Svenson closed them down before they could feed Jago and Rees on the wing. Nepia was always lying in wait anyway.

Albert Gibson and Rafie Hamblin were starved decent possession too. Only fullback Harvey Ham from Redruth emerged from the experience with any credit.

Rafie would later claim that Cornwall’s gracious acceptance of New Zealand’s wish to have both XVs play with a five-eighth formation cost them the match. A seven-man scrum allowed for an extra fly-half, or ‘five-eighth’ outside. Cornwall had never played with such a system before, and it showed. Bert Cooke, a specialist five-eighth, excelled, but then he was probably up against a Cornish forward who had been drafted into the position at the last minute.

Although one suspects Cornwall would have been beaten whatever the formation, Rafie may have had a point. After all, The Originals had employed similar tactics back in 1905, and surely a little homework and practice matches experimenting with the formation wouldn’t have been a waste of time.

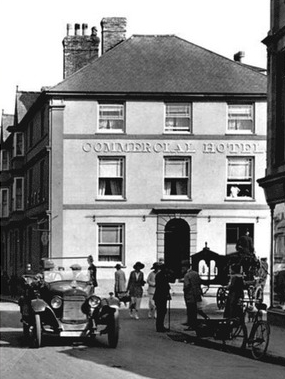

Battered and bruised (Cornwall had been brave, and were frequently hurt in the tackle, so tough and conditioned were their opponents), the local boys had earned a drink. They joined the tourists for a slap-up meal at Camborne’s Commercial Hotel.

New Zealand’s play was rightly eulogised, as was the spirit in which the game was played. Cornwall had shown plenty of guts, but ultimately the All Blacks were superior in every respect.

After their meal, the tourists repaired to the Town Hall, where a dance was laid on. The large number of female spectators at the match had been earlier remarked upon, as had the fact that many of the All Blacks were currently unattached.

What goes on tour, stays on tour.

The next morning, Friday the 19th, crowds gathered in Commercial Square to see the tourists leave. They had other teams to conquer, they would ultimately conquer them all, and would go down in history as the greatest XV to tour the British Isles ever – The Invincibles52.

The people of Camborne had seen something special, something they wouldn’t forget. For those few hours, life in the town wasn’t as bleak. They could leave their concerns behind, and appreciate what New Zealand meant to so many Cornish people: hope.

Maybe the All Blacks sensed this. In the Square they gave the onlookers a private demonstration of their ball-handling skills, which surely thrilled as much as Percy Phillips’ aeroplane.

At the train station, on the platform, the All Blacks turned to face the hundreds of well-wishers and autograph hunters. And there, right there, they performed the Haka, one last time53.

And then, they were gone.

But the memories remained.

With special thanks to: Malcolm Collins (Phil Collins’ grandson); Brett and Kelly Hamblin (Rafie Hamblin’s grandchildren); Leslie Fiedler (Walter’s Mayne’s granddaughter), Hugh Trevarthen (his nephew), and Kathy Oxenham (his niece); Lizzie Mitchell (Fred Barnard’s great-niece); Derek Biddick (Bill Biddick’s son); Peter Thomas (George Thomas’ grandson); Pamela Best (Herbert Wakeham’s daughter).

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is much appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Read all about Camborne’s Feast Day sporting traditions here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/08/26/cambornes-feast-day-rugby/

- From: Cornish Post and Mining News, September 20 1924, p4.

- Cornishman, September 10 1924, p4.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, March 23 1924, p5, and May 3 1924, p5. For more on the decline of Cornish mining, see: John Rowe, Cornwall in the Age of the Industrial Revolution, 2nd ed, Cornish Hillside Publications, 1993, p305-326.

- Image from: Mining in Cornwall: Volume 8, Camborne to Redruth, by L J Bullen, History Press, 2013, p56.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, June 26 1920, p5.

- Cornishman, June 9 1920, p4; West Briton, June 24 1920, p4.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, March 27 1920, p5; April 3 1920, p5.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, June 29 1921, p5; June 21 1924, p5; May 10 1924, p4; April 26 1924, p5.

- Cornubian and Redruth Times, October 20 1921, p6.

- Cornishman, November 3 1920, p3.

- Cornishman, October 4 1922, p6; Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, September 30 1922, p14; 1921 census. For more on the cream of Cornish rugby going North, see: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/02/03/the-great-cornish-rugby-split/

- Image from: Henry Cecil Blackwell, From a Dark Stream: The Story of Cornwall’s Amazing People and Their Impact on the World, Truran, 1986.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, January 19 1924, p5.

- From: Read Masters, With the All Blacks: In Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia, 1924-5. Christchurch Press, 1928, p6.

- From: Philip Payton: The Cornish Overseas: The Epic Story of the ‘Great Migration’, Cornwall Editions, 2005, p256-322.

- As noted in the Cornishman, February 2 1924, p7.

- The make-up of the committee is noted in the Cornubian and Redruth Times, August 7 1924, p5.

- Cornubian and Redruth Times, February 7 1924, p6. The reporter reckoned Camborne would struggle without him. They were wrong.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, August 2 1924, p8.

- West Briton, May 1 1924, p3.

- Cornubian and Redruth Times, February 7 1924, p5.

- Cornubian and Redruth Times, February 7 1924, p5.

- Tom Salmon’s The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall, CRFU, 1983, contains lists of all who represented Cornwall.

- 1921 census, Western Morning News, September 10 1923 p2; Cornishman, November 29 1934, p9. For more on the career of John Collins, see: https://www.epcrugby.com/european-professional-club-rugby/content/rugby-legend-john-collins-reminisces. With special thanks to John’s son, Malcolm.

- 1911 and 1921 census, Cornubian and Redruth Times, October 4 1923, p5; September 4 1924, p6; Cornishman, October 24 1923, p4; West Briton, December 16 1976, p19. With special thanks to Lizzie Mitchell, Fred’s great-niece.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, April 16 1927, p6; September 17 1927, p6; October 6 1928, p6. Cornishman, December 15 1932, p3; August 23 1934, p7. West Briton, June 30 1932, p7; November 8 1990, p41. With special thanks to Rafie’s grandchildren, Brett and Kelly Hamblin.

- Cornishman, August 3 1927, p2; West Briton, September 15 1927, p3; February 9 1928, p3; Janaury 5 1984, p6; Cornish Post and Mining News, September 10 1927, p3. Camborne RFC Centenary Handbook, 1878-1978. Biddick was a Private in the 1/5th regiment, DCLI, #2486/240390, which saw action on the Western Front between 1926 and 1918: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Duke_of_Cornwall%27s_Light_Infantry. With special thanks to Derek Biddick, Terry Symons, and Roger Moyle.

- Walter’s story is summarised from: Henry Cecil Blackwell, From a Dark Stream: The Story of Cornwall’s Amazing People and Their Impact on the World, Truran, 1986, p213-220. Though Blackwell’s book credits George Jago with introducing the game to Yale, he was only in the USA for little over a year: Cornishman, April 25 1929, p6; West Briton, December 25 1930, p12. See also: 1921 census, Cornishman, August 4 1926, p7; West Briton, June 22 1972, p3. For more on Chicago’s Crane Co., see: https://www.craneco.com/about/history/. For more on Major League rugby in America, see: https://www.majorleague.rugby/history/. With special thanks to Leslie Fiedler, Walter’s granddaughter, Hugh Trevarthen, his great-nephew and Kathy Oxenham, Walter’s niece.

- See: Western Morning News, January 3 1921, p3; July 5 1921, p2. Cornubian and Redruth Times, August 30 1924, p8; September 25 1924, p5. London Daily Chronicle, December 6 1924, p9. Cornish Post and Mining News, April 17 1926, p3; January 29 1927, p2. We know Herbert was back in Cornwall by 1935; he was in court for fighting on a bus to Hayle: Cornish Post and Mining News, December 21 1935, p8. For more on the infamous 1926 Camborne -Redruth derby, see: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/09/02/camborneredruth-the-oldest-continual-rugby-fixture-in-the-world-part-one/. See also: 1921 census, Herbert’s obituary (West Briton, April 18 1963, p11), UK, British Army World War I Medal Rolls Index Cards, 1914-1920 for Seth H Wakeham, here for Transvaal’s Pirates RFC: http://piratesclub.co.za/. With special thanks to Pamela Best, Herbert’s daughter.

- See: Cornish Post and Mining News, September 9 1933, p6, which contains a profile of George. Swedish drill image from: https://shop.memorylane.co.uk/mirror/0000to0099-00080/scout-sports-kingston-display-swedish-drill-21381495.html. See UK, British Army World War I Medal Rolls Index Cards, 1914-1920 for Sgt 2471/240385 George Thomas, DCLI. With special thanks to Peter Thomas (of New Zealand), George’s grandson.

- Thirty minutes of precious Invincibles footage can be viewed here: https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F7026/. Sadly, the film crew were not present for the fixture against Cornwall.

- Still from the short film on Phillips: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-SSn0g7pYTM

- Cornish Post and Mining News, September 20 1924, p4; Cornish Guardian, November 28 1924, p5. Tragically, Phillips died in a ‘plane crash aged 45 in 1938. See: http://www.gamlingayhistory.co.uk/james-browns-blogs/a-poignant-death/, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-SSn0g7pYTM, https://www.cornishmemory.com/item/CHA_05

- Thirty minutes of precious Invincibles footage can be viewed here: https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F7026/. Sadly, the film crew were not present for the fixture against Cornwall.

- Thirty minutes of precious Invincibles footage can be viewed here: https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F7026/. Sadly, the film crew were not present for the fixture against Cornwall.

- From: https://lynn.substack.com/p/will-the-nz-government-be-a-party

- Yorkshire Evening Post, October 11 1905, p3. For more on the 1905 Tour, see: Fifty Years of The All Blacks, ed. Wilfred Wooller and David Owen, Sportsmans Book Club Ltd, 1955, p13-56.

- For more on Jackett, Davey, and the Cornish XV of the early 1900s, see: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/13/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-three-a-modern-bartram/, and https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/07/20/in-search-of-john-jackett-part-four-the-king-of-cornish-sport/

- Cornish Post and Mining News, September 20 1924, p4. That Cornwall had a chance against New Zealand was something of a joke.

- For a report of the Devon match, see: Cornubian and Redruth Times, September 18 1924, p6. The 1925 newsreel footage of the Tour calls the players ‘Invincible’: https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F7026/.

- Image from: Read Masters, With the All Blacks: In Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia, 1924-5. Christchurch Press, 1928, p18.

- See: https://lynn.substack.com/p/all-hell-breaks-loose-after-auckland

- See Lynn McConnell’s articles: https://lynn.substack.com/p/all-hell-breaks-loose-after-auckland, and https://lynn.substack.com/p/11-cliff-porter-captaincy-surprise

- Read Masters, With the All Blacks: In Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia, 1924-5. Christchurch Press, 1928, p1-14. The All Blacks’ presence at the Camborne-Torquay match is mentioned in the Cornishman, September 10 1924, p6.

- Image from: Read Masters, With the All Blacks: In Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia, 1924-5. Christchurch Press, 1928, p1-14. The All Blacks’ presence at the Camborne-Torquay match is mentioned in the Cornishman, September 10 1924, p18. See Lynn McConnell’s account of the match (and Nepia’s play) here: https://lynn.substack.com/p/17-referees-get-under-all-blacks. For more on John Jackett, see: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/06/29/in-search-of-john-jackett-king-of-cornish-sport-part-one/

- Cornishman, September 10 1924, p6.

- Tom Salmon’s The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall, CRFU, 1983, p117; Cornish Post and Mining News, September 20 1924, p8.

- The match is summarised from reports in: Cornish Post and Mining News, September 20 1924, p4, 8; Cornubian and Redruth Times, September 25 1924, p6, and https://lynn.substack.com/p/17-referees-get-under-all-blacks

- Thirty minutes of precious Invincibles footage can be viewed here: https://www.ngataonga.org.nz/search-use-collection/search/F7026/. Sadly, the film crew were not present for the fixture against Cornwall.

- See above.

- See: Fifty Years of The All Blacks, ed. Wilfred Wooller and David Owen, Sportsmans Book Club Ltd, 1955, p57-94, and Read Masters, With the All Blacks: In Great Britain, France, Canada and Australia, 1924-5. Christchurch Press, 1928. Neither book gives much space to the matches against Cornwall.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, September 20 1924, p8.

One thought on “The Magnificent Seven Meet The Invincibles”