Reading time: 30 minutes

Through all the ways of our unintelligible world, the trivial and the terrible walk hand in hand together… ~ Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White (1860)

Jarndyce and Jarndyce drones on. This scarecrow of a suit has, over the course of time, become so complicated, that no man alive knows what it means. The parties to it understand it least; but it has been observed that no two Chancery lawyers can talk about it for five minutes without coming to a total disagreement as to all the premises… ~ Charles Dickens, Bleak House (1853)

Legends…make what are perceived to be extraordinary claims. Because legendary narratives tend…to make such claims, they require the deployment of a rhetoric to ally doubts and foil challenges. ~ Elliott Oring, “Legendry and the Rhetoric of Truth”, The Journal of American Folklore, 121.480 (2008): p127-166

She called herself The Duchess of Cornwall, they said. She claimed there was a plot to take away her property, or even poison her, they said. She believed listening devices were in the walls of her homes, they said. She’d ordered her gardens to be dug up, to locate the tunnel she imagined her enemies used to infiltrate her mansion, they said.

She carelessly left piles of cash unattended in her rooms. Her wealth was indeed bordering on the incalculable.

She wrote rambling letters full of fantastic – and accusatory – tales.

She issued her butler pistols with which he was to shoot employees of the Marquis of Westminster.

She laid claim to the throne of England, and was alleged to have stated that Queen Victoria had been sentenced to death.

Small wonder, then, in December 1843 a jury found that Mary Hartley nee Harris was

…of unsound mind, and incapable of managing herself or her affairs…

With almost supernatural powers of precision, the same jury backdated her insanity to having commenced on October 31, 18341.

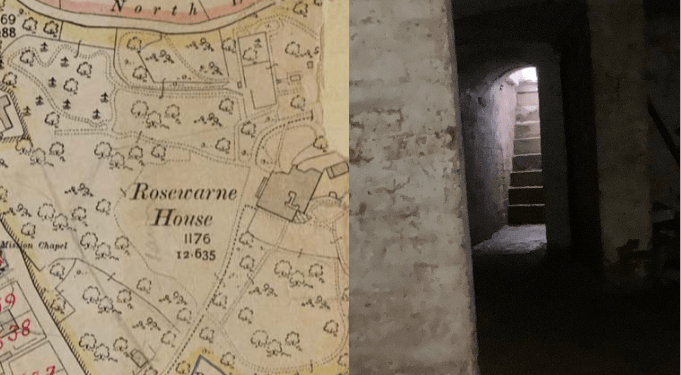

Yes, in modern parlance, Mary Hartley was stark raving mad. She became a solitary, reclusive figure on her Rosewarne Estate in Camborne, a figurehead of Cornish gentility shorn of the power to administer her vast inheritance. Meanwhile, the legends grew, serving to further reinforce the judgment handed down to her in 1843. By 1871 it was remarked of her that she believed Rosewarne to be infested by serpents2.

Of course, by now Hartley herself could neither confirm nor deny this particular rumour.

In 1868 Cornwall’s own ‘madwoman in the attic’ cemented her reputation for all time as a raving lunatic. Whether by accident or design is unclear, but alone in her rooms at Rosewarne one dark night, Mary Hartley burned to death3.

Surely such an horrific demise was reserved solely for those on society’s margins, such as the insane? To be sure, Mary Hartley wasn’t the last Victorian madwoman to go up in flames, or meet a similarly gruesome end5.

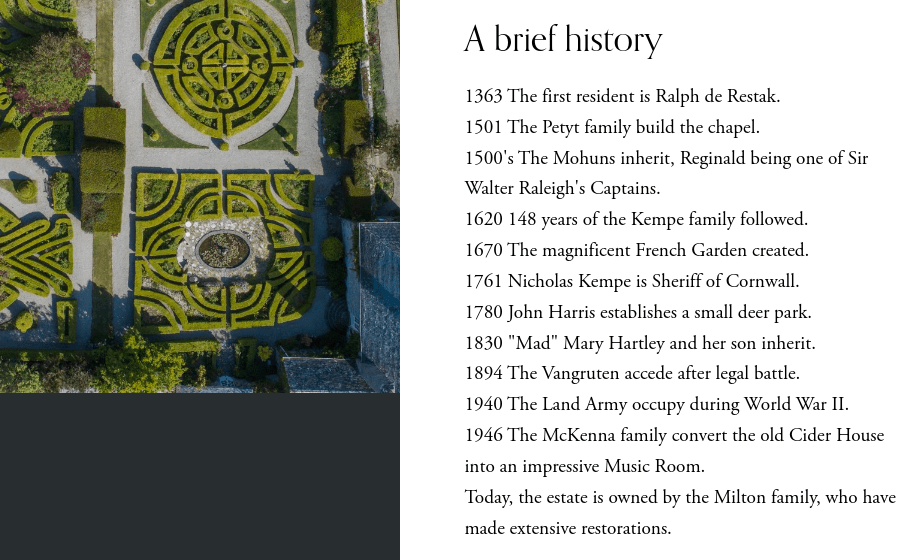

You may think my tone is somewhat insensitive. But isn’t Mary Hartley’s madness a well-known and accepted fact? Professor Brown’s in-house guide to Rosewarne gives the story ample coverage. Her name on the list of Rosteague’s owners (see image above) is preceded by the sobriquet “mad”.

But, due to the harrowing circumstances of her death, the estate of Rosewarne is the one with which Mary Hartley is most often associated. She was mad, as was her son, William Henry Harris Hartley (1823-94). He had been judged to be as mad as his mother at the conclusion of the 1843 investigation. It was this double-madness that generated decades of litigation into confirming the rightful heir of Rosewarne, Rosteague, and everything else that had landed in Mary Hartley’s lap.

But this post isn’t overly concerned with the painfully convoluted inheritance trials, which after all are pretty common knowledge. A piece on the subject would take years to write, and I would require extensive legal training.

What concerns us here is the manner in which Mary Hartley’s insanity has, since 1843, been generally accepted as gospel.

It’s the contention of this post that, for people to benefit from the Harris/Hartley wealth, Mary had to be insane. If the poor lady was, in fact, sane, then there would have been no protracted (and costly) legacy hearings, hearings realised at the time as notably profligate:

…for centuries estates have vanished from rightful owners, Chancery hugged its spoils, and its myrmidons laughed and grown fat.

The motivations of those involved might have been questioned, but Mary’s sanity wasn’t. Cornishman, July 8 1897, p5

To begin to understand why Mary Hartley may not have been as deranged as is often made out, we first need to trace the facts of her life up to 1843. Then we also need to consider the judgment made on her as insane in its historical context. Then we can ask another question: cui bono – who benefits?

Thus, Mary Hartley might be remembered more as an actual human being, rather than a Victorian caricature of a raving yet rich heiress too insane to be even seen in society, whose tragic end is oddly fitting.

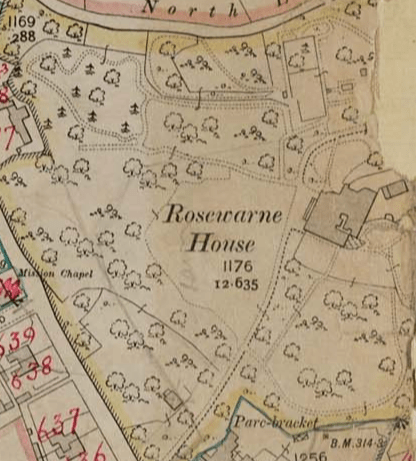

Mary’s grandfather was Thomas Harris (c1701-88), a scion of the wealthy Devonshire Harris family. By the 1740s he was the owner of the manor of Roswarne Wartha, or Higher Rosewarne, and had a healthy interest in Cornwall’s boom industry: mining6.

In 1749 he struck a deal with another up and coming mineral entrepreneur, Christopher Hawkins of Trewinnard, St Erth. Hawkins had permission to open a sett on Higher Rosewarne to mine for copper and tin; Harris of course got a percentage of the profits. Soon, the money began to roll in, and Thomas, along with his two sons William (c1738-1815), and Henry (c1749-1830), could extend his family’s operations and influence7.

By 1775, stamping mills had been erected at Rosewarne, and the mine became known as Wheal Chance. In 1779 its engine house was due an upgrade, and the builders were given three weeks to do the job9.

And the cash kept piling up. William Harris was involved with the Cornish Copper Company, who purchased properties from him in 1779 worth £4,000, or £584K today10. The family had interests in the Camborne/Tuckingmill setts of Wheal Gerry, Wheal Hatchet, Wheal Vernon and Wheal Lovely11, Wheal Crenver at Crowan12, Penhale near Carnhell Green13, Nancemellin near Gwithian14, and setts at Barripper and Penponds15. (This list is far from exhaustive.)

With the money from mining, came power. By 1773, William Harris was Sheriff of Cornwall16. He held lands at Roseworthy, St Breock, Crowan, and Godolphin Manor at Breage17.

In 1768, Thomas Harris had acquired the ancient manor of Rosteague, on the Roseland peninsula. This he bequeathed to Henry18.

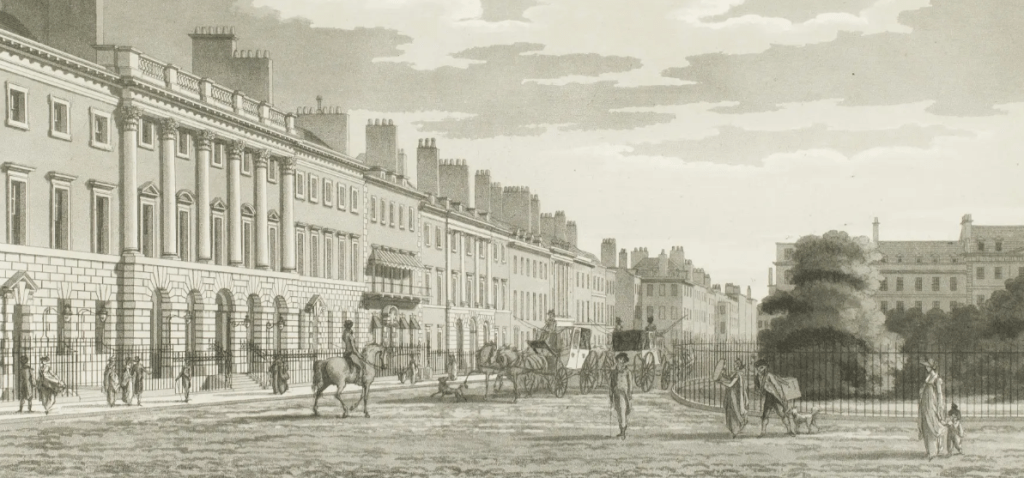

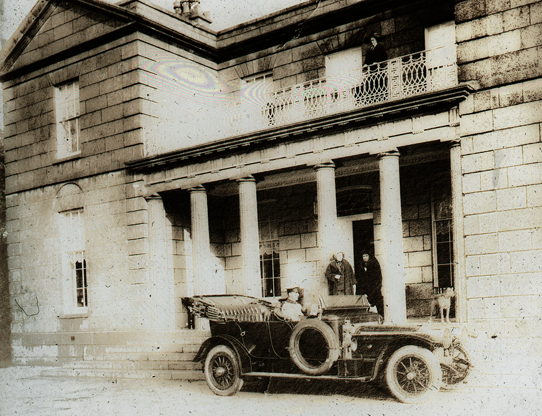

William got Higher Rosewarne. At this point the property probably resembled Roswarne Wollas, or Lower Rosewarne, itself the proud possessor of a colourful history19. Evidently desiring a dwelling befitting a man of his station (and doubtless wanting a pile as grandiose as his kid brother’s), William set about developing Rosewarne into the beautiful, neo-classical Georgian mansion we see today20.

William Harris probably never saw the completion of Rosewarne; he was dead by December 1816. He also never saw how much the industry he invested so heavily (and so successfully) in would transform Camborne. If he had intended Rosewarne to be a country retreat along the lines of the Basset family’s Tehidy Estate, he was to be mistaken.

In around 1819 the town’s population was estimated to be around 400; by 1880, the total was put at 7,000. Tuckingmill, once a village, had been swallowed up, and Treswithian was under threat. Rosewarne was now very much a town-house22.

On William’s death, Rosewarne went to his daughter Mary, who had been born in 1791. When her uncle Henry died without issue in 1830, Rosteague became hers too. Mary also took possession of houses on The Crescent, Bath, and Grosvenor Square, Mayfair. In 1843 her estates generated an annual income of £5,000. In 2024, that figure would be £533,840/annum23.

Mary was stupendously wealthy, and apparently at all times

…exhibited self-will and eccentricity, such as is usually observable in rich heiresses and only children…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4

So, Mary was a spoilt rich brat, as well as later going mad? The above statement was made by Sir William Carpenter Rowe (1801-1859), a lawyer from Launceston who became Chief Justice of Ceylon24. He made this appraisal of Mary’s character in support of the investigation into her alleged lunacy in 1843. He was presenting his opinion of her personality to realise the commission’s goal: to have Mary declared insane.

Therefore Rowe’s statement is unreliable. You could infer, though, that Mary was independently-minded and possibly rebellious, and didn’t fit neatly into the Regency/Victorian ideal of a chaste, obedient and meek lady.

In 1819 she ran away and married, at the British Embassy in Paris, Winchcombe Henry Eyre Hartley (1773-1847), a judge who had been employed in South Africa. It’s hard to ascertain, over two hundred years later, what exactly Mary’s motivations were26.

She might have married – against her family’s wishes – genuinely from love. Or, it might have been a match made on the rebound: her involvement with a Penzance gentleman had been thwarted by the Harris seniors27.

In contrast it’s relatively straightforward to unravel Eyre Hartley’s intentions. A widower, he had five children by his first wife, Lady Louisa Lumley-Saunderson (1773-1811). She was a daughter of the 4th Earl of Scarborough, a peer of the realm whose ancestor had put a King on the throne of England28.

Having married into money, land and power once, with Mary, Eyre took the opportunity to do so again. He also got a bride twenty years his junior and may have hoped for a compliant wife to tend him in his dotage.

At first, he was proved right. Mary’s dowry (held in trust by Sir Christopher Hawkins, who’s not to be confused with her grandfather’s old business partner) included the parish of Kenwyn, land at Penponds and various mining interests29.

Obviously, as Eyre’s wife Mary also surrendered any legal rights she may have had. Georgian England had a value system so patriarchal one commentator has remarked that

…a married woman was the nearest approximation in a free society to a slave…

Laurence Stone, Road to Divorce: England, 1530-1987, Oxford University Press, 1990, p13

With the birth in 1823 of their son William, Eyre Hartley ensured the Harris wealth would now go to his family.

But all was not well with the marriage. Shortly after William’s birth, the couple executed what was known at the time as a deed of separation. Hawkins and the noted St Erth engineer Davies Gilbert were the deed’s trustees30.

Carpenter Rowe lays the blame for their breakdown of relations solely at Mary’s door, citing the

…temper of the lady and her eccentric habits…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4

But then he would say that. In order for Mary (and lest we forget, her son) to be declared insane, her reputation must be made as questionable as possible. If that meant implying that she was half-way down the road to the asylum in the 1820s, then so be it.

In truth, there is no evidence whatsoever to suggest why Mary and Eyre could no longer cohabit. It could just as easily have been Eyre’s temper and eccentricity that precipitated the separation. In fact, that is exactly what Mary said before the Lunacy Commission of 1843 – but nobody listened31.

Mary got custody of her son. Eyre had to relinquish the assets included in Mary’s dowry, but still received annual payments from her estates. In 1825 Mary finalised her will, which made it plain that Eyre Hartley or any member of his family was to have nothing to do with her property33.

A separation is not a divorce. Eyre Hartley had married money twice, and both times failed to realise lasting riches. A third attempt was now out of the question. Mary was effectively a well-off single mum for the rest of her life.

In the late 1820s, Sir Christopher Hawkins, along with Davies Gilbert, decided Mary was incapable of managing her estates by herself. By 1830 a suit in Chancery was granted and John Tyacke, a businessman and oyster farmer of Merthen Manor, Constantine, was appointed to receive the rents34.

The conventional image of Tyacke is that of a trusted and loyal confidante of Mary35. But we might be well advised to remember that the man mainly responsible for his appointment, Hawkins, was probably the most avaricious and corrupt Cornishman of the whole Georgian era36.

Luckily for Mary, he was dead a year before Tyacke took up his station. If Hawkins did have designs on her wealth, orchestrating one of his proteges to collect the money was certainly one way to go about it.

Therefore we have to ask if Mary was truly incapable of managing her estates at this stage, or did Hawkins (with Gilbert) manipulate the whole suit for his own ends? Certainly, Tyacke made the most of his situation. In 1844, he was selling Rosteague’s deer – but where was the money going?38

And Mary clearly bridled at the arrangement, on two points. First, that she still had to hand over an annual sum to Eyre Hartley; second, that Tyacke controlled the purse strings. In 1832 he was ordered to pay Hartley’s annuity,

…despite wishes of Mary Hartley…

Kresen Kernow, ref. FS/3/1547/7

In 1841 a labourer on the Rosteague estate was dismissed for paying his rents directly to Tyacke, and not to Mary. Tragically the man became so confused and disheartened he later killed himself39.

Is it really very surprising, therefore, that Mary began to suspect people had nefarious designs on her wealth, that her Harris inheritance might be wrested from her?

She had an estranged husband whom she claimed had been abusive, yet could still profit from her property. Small wonder she petitioned Parliament for an actual divorce40. She had another man, Tyacke, foisted upon her and who, in collecting her rents, was surely acting as if he himself was lord of the (many) manors.

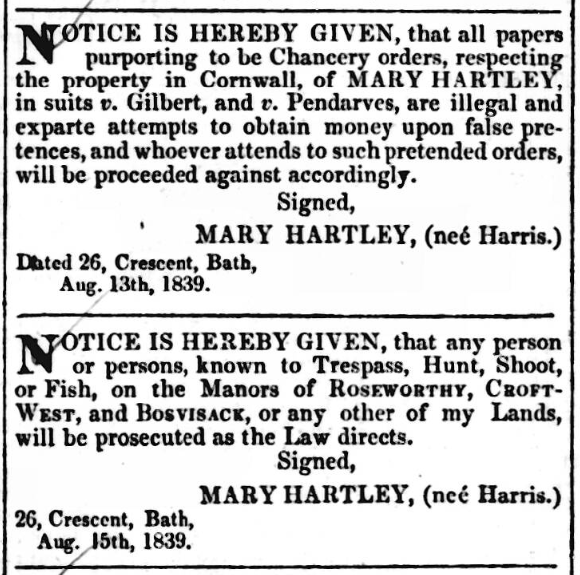

She made regular attempts to reassert her authority, an authority that was rapidly diminishing:

Desperation was setting in. Mary began to style herself ‘Duchess of Cornwall’ in person and in writing, tooled around Bath in a coach-and-four emblazoned with complex coats of arms, and had her rooms decked out in the manner of a monarch of ancien regime France41.

Lawyers, men of standing and Mayors were bombarded with letters, telling stories of conspiracies to steal her fortune:

…I must request that the town clerk may not be consulted, as it is publicly known that the system of eavesdropping, &c…at his house is connected with the difficulties of my case in various ways…

London Weekly Chronicle, December 10 1843, p3

More than one exasperated solicitor abandoned her completely, leading to a certain unravelling in her estates’ affairs42.

All of which served as grist to Mary’s mill. Very soon, people were genuinely acting to release her from the cares of her wealth and property.

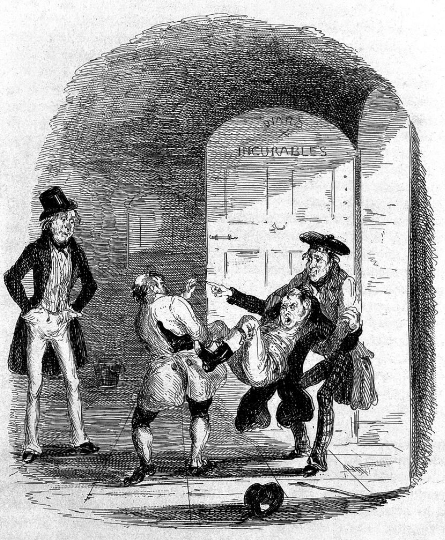

With the passing of the 1828 Madhouse Act, two people (often relatives of the suspected lunatic) had to notify two different doctors in writing of their concerns. The doctors would each interview the subject and, if required, sign certificates of lunacy44.

Maybe the individuals who first expressed their concerns for Mary’s (and her son’s) sanity genuinely had her best interests at heart. Maybe they sincerely believed the woman needed help.

However, the duo in question here were Winchcombe Henry Hartley (1803-1858), a son of Eyre Hartley by his first marriage, and Lady Louisa Saville, the aunt of Eyre’s dead wife, Louisa Lumley-Saunderson45.

As noted earlier, Mary’s will of 1825 had debarred any of the Hartleys from succeeding to her estates. True, Eyre Hartley received a healthy annuity, but what about the real money? If Winchcombe and Louisa could get Mary declared mad, along with Winchcombe’s own half-brother, William, then might not the will of 1825 be invalid..?

If that proved too ambitious, then might not the Hartleys contrive to benefit in some other way?

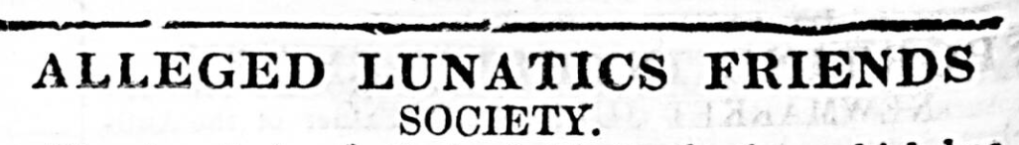

This may sound cynical and melodramatic, but wrongful incarcerations happened regularly in the early Victorian period. Eccentric, simple-minded and wealthy persons could find themselves certified insane at the hands of their own kin and flung in an asylum, whilst the same unscrupulous relatives took control of the cash47.

In fact, so often were perfectly sane people being thrown in the madhouse, that a pressure group formed to investigate any serious cases, and rescue the unfortunate victims. They called themselves the

Though Mary’s case was covered by the London ‘papers, sadly the Society didn’t come to her aid. They didn’t have the wherewithal to take on the Court of Chancery, and assisting allegedly mad women wasn’t really their thing anyway48.

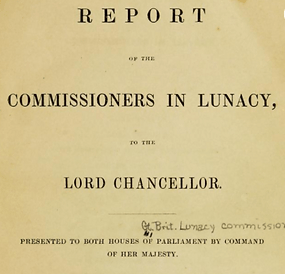

Mary would not be confined in an asylum. She would become a particular private patient known as a ‘Chancery lunatic’, whereby her money and property would be under the protection of the Lord Chancellor49.

Representing the Chancellor in the day-to-day care of the patient and the administration of their affairs, would be two persons appointed by the Court of Chancery. These officials were paid a percentage of the estate’s wealth, and could claim expenses on the said estate50.

Before all that could happen, as a possible ward of Chancery Mary’s state of mind would be investigated at a hearing (for her case, in London) by the Government’s Lunacy Commission. A de lunatico inquirendo, or lunacy inquisition was to be held under the auspices of the Master in Lunacy, Francis Barlow51.

Barlow had a jury of 18 magistrates in tow, who all listened to a speech lasting six hours by Sir William Carpenter Rowe, the man appointed by Winchcombe Hartley and Louisa Saville to get Mary certified.

Mary chose not to attend, which was probably a good thing. She hadn’t have many friends in the room, and her defence is all-but silent in the reports.

One Bath lawyer told of how the woman had pestered him with her voluminous, barely-coherent letters for over two years. One suspects no lawyer likes to be bothered with a case they can’t hope to win.

A tax collector told of how she refused to pay, styling herself Duchess of Cornwall on the returns and stating she had legal claims on the crown. Surely, all tax collectors prefer people who pay up without hassle.

John Tyacke spoke of how Mary had appointed him to manage her estates in 1831, and that she turned against him when Chancery made him the receiver. She had had men digging up the gardens at Rosteague, he said,

…to find out how her enemies got into the house…she was not right in her mind…

She had apparently accused him of treason, and tried to have him arrested. Tyacke owed her no favours.

A butler whom Mary had recently dismissed claimed she had given him pistols with which to shoot the workmen employed on the Marquis of Westminster’s house. She wouldn’t handle sovereigns with the Queen’s head on them, he said,

…as she had a title to the throne…no sane person would speak in the excited way she did…

Others gave similar stories, of imaginary serpents, listening devices, and turning her back on the monarch.

Of course, the witnesses may have thought they were acting in Mary’s best interests – or they may have told Barlow and the jury what they believed the officials wanted to hear.

Either way, it played into Winchcombe Hartley’s hands. One witness had

…no doubt as to her insanity…

There was one false note amongst all these testimonies. And that came from Mary herself.

Four days into the inquisition, the jury decided they ought to hear from the unfortunate woman herself. With Commissioner Barlow, they visited Mary at her home in Grosvenor Square.

If they were expecting to encounter a semi-demented, drooling paranoiac, they were wrong. The Mary Hartley they met was lucid and obstinate. Like other potential lunatics interviewed by Barlow, she clearly had little time for the man54.

Barlow asked her if she believed she had any claim to the crown. The reply was curt:

Certainly not. What claim could I, as simple Mrs Hartley, have to the crown?

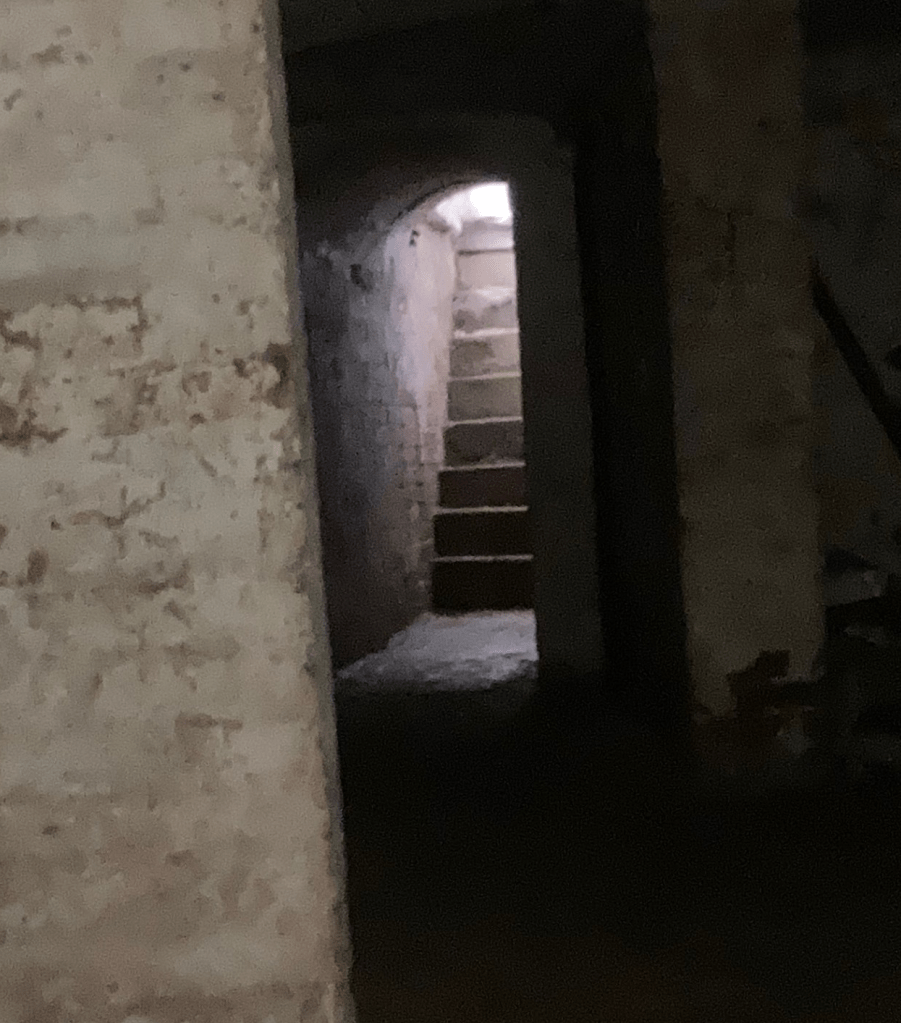

Barlow then asked her about the digging at Rosteague to discover the conspirators’ entrance:

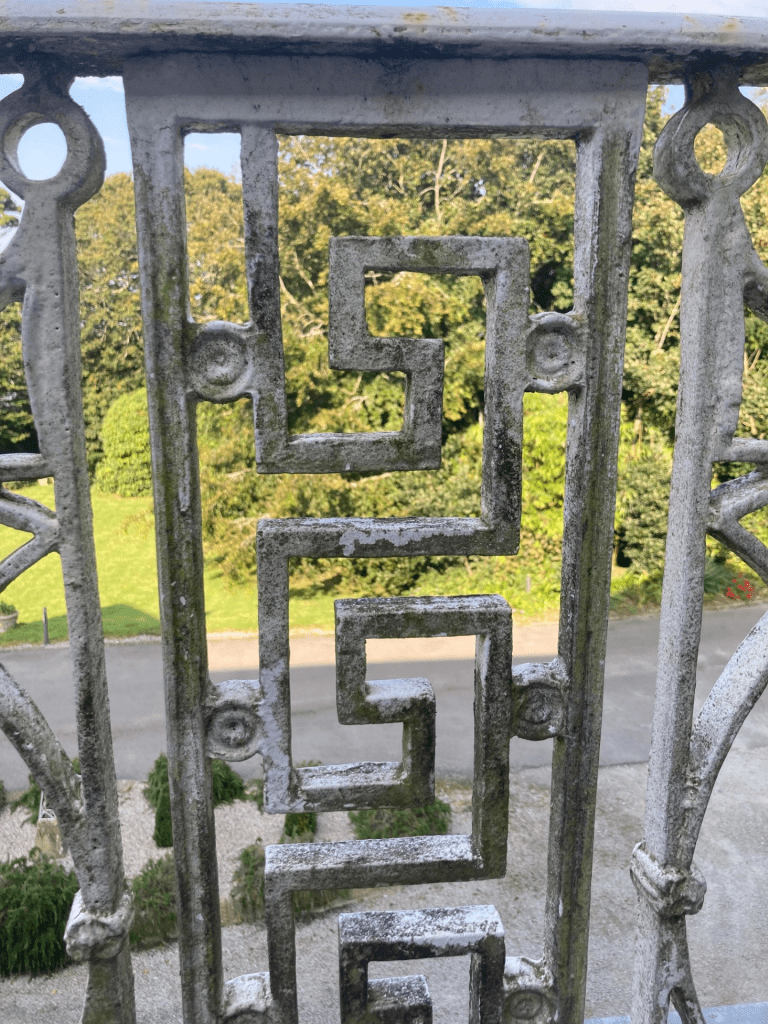

…not for that reason. There was an old tradition…that there was a subterraneous communication between Rosteague and the sea, and I was anxious to ascertain the fact.

(There certainly was a tunnel leading from Rosteague to the sea, though it has long since vanished55.)

What about the noises in her various properties?

…they might have been occasioned by rats, or any other cause.

Clearly Barlow was irritating Mary. When he asked her why she had driven her carriage right past the Queen’s own, she snapped back

I shan’t tell you that. It is not your business. You let me off the insanity, and then I am ready to enter upon the case of treason…I am anxious to have my affairs out of Chancery…

What did she have against John Tyacke?

…he made up his accounts in the Court of Chancery £250 more than he really ought…

And the box from which Mary claimed to communicate with the Foreign Ministry?

You can’t call that insanity. It was only a joke…

One doubts Barlow saw the funny side. Next she was asked about the pistols and her murderous designs on the Marquis’ workmen. Mary was ready:

…they [the workmen] used to jump over the wall of the back-yard…the house was quite invaded by them. I ordered the servant to fire at them to frighten them, but not to hurt anybody.

You have to admire her nerve. Mary was facing a government agent and an 18-strong jury. But it was too little, too late.

On Friday, December 8 1843, the commission and jurors assembled to give their verdict, with Mary and her son in attendance. It was noted she spoke with a certain “incoherency”, and that

…her whole deportment was strange.

She was about to discover whether she was insane, with all that that entailed. Mary could perhaps be forgiven for being on edge.

Though her defence argued that a delusion did not imply general lunacy, this time Barlow was prepared. It’s not known from which authoritative tome he quoted, but it was probably A Treatise On the Law Concerning Lunatics, Idiots and Persons of Unsound Mind (1833). After all, he would use it in at least one other case. The crucial lines are:

A sound mind is one wholly free from delusion…An unsound mind is marked by delusion, mingles ideas of imagination with those of reality…the true test of the absence or presence of insanity, may be comprised in a single term, viz, delusion.

Qtd in Sarah Wise, Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty and the Mad-Doctors in Victorian England, Vintage Books, 2012, p171-3. Barlow quoted these words to prove another patient’s insanity.

Though it’s not mentioned, Mary’s alleged insistence that Queen Victoria was not the true monarch would have counted against her. By the time of Mary’s certification, there had already been three attempts on Victoria’s life in her short reign56.

Mary was declared mentally unsound, was freed of all worldly concerns, and all that was hers put under the protection of the Court of Chancery.

The very next day, Mary’s son William was judged insane, incoherent, irrational and possibly suicidal by the same commission; he was twenty58. Put yourself in his situation. His mother had just been categorised as a lunatic by the machinations of her stepson, Winchcombe Hartley. Now the same man, William’s half-brother, was about to do the same to him.

He had never known his father. Eyre Hartley left for Europe when he and Mary separated and spent the rest of his life abroad. Living alone with an eccentric and over-protective mother who denied him the company of other children, William can’t have been the most worldly or well-adjusted of men59.

Now, his entire world had been turned upside-down. The events of the previous twenty-four hours had very possibly traumatised him. A stronger character might have steeled themselves to come out fighting, but William was simply not made that way. His intellect, it was written, had “failed”60.

A music-lover who was a familiar face at concerts, William became an object of curiosity in Camborne. It seems strange to read of him being driven about in an open carriage, all 300lbs of him in a white silk top-hat, through a modern 1890s town that was fully industrialised and no longer a small ‘Churchtown’. He must have been seen as a quaint, if odd, throwback to the Georgian era61.

Back to 1843. Mary and William moved back to Rosewarne. The Hartleys – literally – moved in too.

In 1851 Rosewarne’s head and Chancery Committee appointee was William Price Lewis (1812-1853). His first wife had been Louisa Arabella Hartley (1803-1847), a daughter of Eyre Hartley and therefore Mary’s stepdaughter. Arabella’s brother was of course Winchcombe Hartley.

Their three children were still living at Rosewarne in 1861, along with William Lewis’s second wife, Cecilia Bassett Rogers (d1868). Cecilia was now one-half of the Chancery Committee with her brother Francis, a solicitor62.

All their wants and needs were provided for by the Court of Chancery, who funded them through the returns from Mary’s estate. It can’t have been a frugal existence.

How much cash, exactly, are we talking about here? In 1882 the Chancery appointee at Rosewarne was Frederick Townley Parker. He had links to the Hartleys through his wife, and received £2000/annum for the upkeep of Rosewarne. That’s around £202K today63.

It was also rumoured that a Hartley family member was receiving £600/annum from the estate, in direct contravention of Mary’s will of 1825. Today, that person would be earning £60K a year for nothing64.

Townley Parker evidently lived the high hog. The 1891 census shows that Rosewarne boasted a butler, a groom, two footmen and five servants. This army of staff had to tend the needs of two men, William and Townley Parker himself. Why not? Townley Parker certainly wasn’t paying.

Long before this, though, the Hartleys were taking an even firmer grip on the estates of Rosewarne and Rosteague. In 1871, three years after Mary’s horrific death, Charlotte Van Grutten (1831-1874) was named heiress-at-law and would succeed William. She was a daughter of Winchcombe Hartley, who had married a French count65.

By 1877, the Lunacy Commission reported to the Lord Chancellor that Charlotte’s son, Lucien Van Grutten (1862-1932), was now heir-at-law. He was already taking £300/annum (£24K in 2024) from the estates to pay his way through school66.

You might be lulled into thinking, then, that Lucien’s succession would be a peaceful one, but far from it. As early as 1882, members of the Harris dynasty were preparing for an inheritance battle royale67.

In other words, quite a few people, many of them his own kin, were waiting for William to die. He wouldn’t oblige them until 1894. He also died intestate, though anything he’d put his name to after 1843 would have been automatically invalidated.

The vultures closed in.

The inheritance suit was only definitively concluded in 1907, when Lucien Van Grutten was belatedly confirmed as the one true heir of estates valued in 1901 at a staggering £112,937. That’s £11.5 million now69. The suit was variously described in the Press as being

…one of such considerable importance in point of the law…that it has practically become a test case…

Cornish Post and Mining News, July 27 1899, p5

…or, alternatively, a

At least one litigant went bankrupt as a result. There’s claims and counter-claims, appeals and still more appeals. There’s deeds and probates, wills and codicils. There’s fee simples, fee entails and disentailing deeds. There’s hired Irish thugs. There’s Harris descendants from Australia and America, armed to the teeth with more genealogical data than Ancestry could ever hope to obtain.

There’s battalions of lawyers who could convince a jury that black was white, or vice versa if it suited them. There’s repartee, jargon, statutes and precedents70.

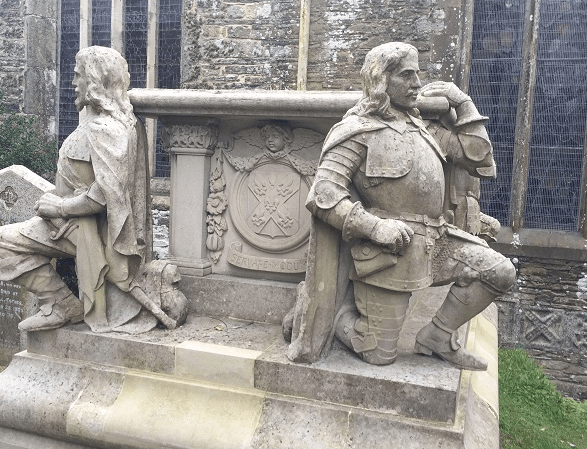

Yes, it was a sickening waste of money. But perhaps most sickening of all is how not one of Mary and William’s Harris relatives came to their aid back in 1843. All that concerned them was the wealth – just like the Hartleys. The Harris clan only acted, rapaciously, after William and Mary were interred in the family vault at Camborne Church71.

Nobody questioned the twin-verdicts of 1843. The only issue surrounding Mary’s state of mind was when she was truly insane.

For example, during the first inheritance hearing of 1895, the Van Grutten side submitted a deed made by Mary in 1835 – a disentailing deed. This, it was argued, reversed the wishes of her will of 1825, thus enabling the Hartley/Van Grutten line to succeed. (One doubts this was Mary’s actual intention.)

The claim was quashed by the Harris party. Mary was already insane by October 31, 1834. Anything she put her name to after this date was obviously open to objection72.

In contrast, back in 1871, a court attempted to prove a codicil to her will that Mary made in January 1834 – when she was of sound mind. The judge denied the codicil’s standing on the grounds that

…the jury [in 1843] did not negative the proposition that she had been lunatic before ’34, only saying that she had been at the time…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, Janaury 28 1871, p8

In one instance, Mary was conclusively insane on October 31, 1834. In another, her insanity could be conveniently backdated. Black is white, and white is black.

At the conclusion of the inheritance suit in 1907, Camborne’s own ‘Bleak House’ was in a state of disrepair73. Before 1914, James M. Holman, MD of Holman Bros and one-time rugby pioneer, had purchased Rosewarne. By 1950, it was the firm’s administration block74.

In the mid-1960s, Rosewarne was bequeathed to the Spastics Society by the Holman family, and renamed Gladys Holman House. From 2013, when the Price family purchased Rosewarne (renaming it Roswarne), the building has been restored to its former Georgian glory. To visit now is to gain a sense of the rural retreat old William Harris had once surely envisaged75.

All the while, the sad story of Mary Hartley was told and retold, and the legends grew. Her ghost was said to be seen at Gladys Holman House, a pitiful figure dressed in grey. But that’s not all.

In 1871, it was remarked of the (then-dead) Mary that she hadn’t attended church since 183076. Over the years, this tale has grown. In 2024 I was told that Mary had had secret tunnels dug from Rosewarne’s cellar, one stretching all the way to Camborne Church. This enabled her to go to church unseen, inadvertently fuelling the 1830s rumour of her irreligious ways.

A former employee of Gladys Holman House once claimed to have walked the tunnel themselves, right up to Camborne Church.

However a one-time caretaker has rubbished the story, as has the highly-respected former archivist at Kresen Kernow, David Thomas. A member of Camborne Church for over sixty years (and the present warden), he has never come across any evidence of a tunnel.

Clearly, Mary’s investigation into the whereabouts of the genuine tunnel at Rosteague was too good a story not to be claimed by Rosewarne, and was altered in the transition77.

Mary Hartley believed in the existence of a tunnel at Rosteague – and she was right. She also believed there was a plot afoot to claim her inherited wealth.

She was ultimately right there too, and therein lies the tragedy of her story.

Listen to me discuss Mary Hartley’s story on The Piskie Trap Podcast with Keith Wallis here.

With special thanks to Alan Rowling, who arranged a private tour of Roswarne; Becky Vage, Roswarne guide; Jay Milton, owner, Rosteague; David Thomas, Churchwarden; Pat Herbert, Gladys Holman House.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4, contains a detailed account of the Hartley Lunacy Trial. The hearing and verdict meted out to her son, William, is noted in the St James’s Chronicle, December 12 1843, p2.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 21 1871, p6.

- The jury at the inquest recorded a verdict of accidental death: Royal Cornwall Gazette, October 29 1868, p6. The ‘madwoman in the attic’ refers to a famous character in Charlotte Bronte’s 1847 novel Jane Eyre. The wife of the text’s protagonist, Mr Rochester, is declared insane and kept hidden from view in the mansion’s attic. In 1979 Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar published The Madwoman in the Attic: The Woman Writer and the Nineteenth-Century Literary Imagination, a landmark feminist text.

- Image from: https://www.rosteague.com/about. Hartley’s seasonal use of Rosteague is noted in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, October 29 1868, p6.

- A stricken Norfolk woman burned to death in 1897; a London madwoman cut her own throat in 1830. Lynn News and County Press, January 9 1897, p3; London Evening Standard, January 14 1830, p3.

- See Thomas Harris’s burial record here: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=burials&id=4670368. Professor Brown’s in-house guide to Roswarne notes that Harris’s original Cornish seat had been the manor of Upton, near Hayle, but the ever encroaching sand dunes had forced him to look elsewhere.

- The deal between Hawkins and Harris is held at Kresen Kernow, ref. TEM/143/6. This particular Christopher Hawkins is not to be confused with the later (and more well-known) Sir Christopher Hawkins (1758-1829) of Trewithen, who also features in this story. See William and Henry’s burial entries here: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=burials&id=4645258, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=burials&id=4673812. For more on Trewithen, Trewinnard, and the interlocking of the Hawkins family, see: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1143620?section=official-list-entry, and https://www.trewithengardens.co.uk/our-story/history-of-the-estate

- Image from: L. J. Bullen, Mining in Cornwall, Volume Eight: Camborne to Redruth, History Press, 2013, p10.

- Kresen Kernow, refs. TEM/81/1, AD2258/2/35.

- Kresen Kernow, ref. X473/102.

- Kresen Kernow, ref. EN/1516.

- Kresen Kernow, ref. TLP/694.

- Kresen Kernow, ref. BRA/1489/64.

- Kresen Kernow, ref. TEM/181/3.

- Kresen Kernow, RH/1/438.

- As mentioned in the Salisbury and Winchester Journal, February 15 1773, p1.

- Kresen Kernow, refs. AD/864/68, BRA2355/15-16, X327, RH/1/1859.

- Sherborne Mercury, September 5 1768, p4; Kresen Kernow, ref. BRA/1489/60.

- See: Rosewarne (Cornish Houses and Gardens), by Tamsin Sandfield, Kresen Kernow, ref. 728.8094238. John de Rosewarne rebelled against Henry VII in 1497. See: https://agantavas.com/one-leader-of-the-uprising-john-rosewarne-of-rosewarne-near-camborne/.

- Professor Brown’s in-house guide at Roswarne gives a detailed survey of the property’s architectural heritage.

- Image from: https://www.rosteague.com/gallery

- West Briton, October 18 1880, p1. I’m not going to vouch for the accuracy of those population figures, but you get the general idea. For more on the Basset family, see: Tehidy and the Bassets: The Rise and Fall of a Great Cornish Family, by Michael Tangye, Truran, 2002.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4. Mary’s baptism entry is here: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=baptisms&id=6524940

- From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Carpenter_Rowe

- Image from: https://www.forumauctions.co.uk/130600/Egan-Pierce-The-Life-of-an-Actor-first-edition-hand-coloured-aquatints-original-boards-1825?view=lot_detail&auction_no=1142

- Bristol Mirror, October 9 1819, p3.

- Professor Brown’s in-house guide at Roswarne notes this.

- The 1st Earl of Scarborough was one of the men who had conspired to bring William of Orange to England during the Glorious Revolution of 1688. See: https://www.thepeerage.com/p46500.htm#i464997, https://www.thepeerage.com/p46500.htm#i464996, https://www.thepeerage.com/p2600.htm#i25991, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Lumley-Saunderson,_4th_Earl_of_Scarbrough, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Lumley,_1st_Earl_of_Scarbrough

- Kresen Kernow, ref. BRA2355/169-170.

- Without the concerned parties acquiring a private Act of Parliament, divorce was to all intents and purposes impossible in 1820s England. Many well-to-do yet unhappy couples took the same route as Mary and Eyre, but a deed of separation in no way nullified a marriage. Divorce only became enshrined in English law in 1857. See: Laurence Stone, Road to Divorce: England, 1530-1987, Oxford University Press, 1990, p141-3, 368-82. For more on Davies Gilbert, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Davies_Gilbert

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4.

- Image from: https://londonopia.co.uk/the-wife-auctions-of-spitalfields/. For more on wife sales, see: E. P. Thompson, Customs in Common, Penguin, 1991, p404-66, and my post on a wife sale that took place in Redruth in 1819: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/12/10/two-shillings-and-sixpence-a-cornish-wife-sale/

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4; Cornishman, August 31 1882, p7.

- For more on Merthen Manor, see: https://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/library/browse/issue.xhtml?recordId=1146108&recordType=GreyLitSeries. Tyacke was plagued by people stealing his oysters. See: Kresen Kernow, ref. QS/1/13/170.

- Professor Brown’s in-house guide at Roswarne makes this clear.

- For more on Hawkins, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sir_Christopher_Hawkins,_1st_Baronet. He features in my post on parliamentary corruption here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/01/06/the-grampound-potwallopers-corruption-in-georgian-cornwall/

- Image from: https://www.cornwallheritage.com/ertach-kernow-blogs/ertach-kernow-sir-christopher-hawkins-boroughmonger/

- Penzance Gazette, October 23 1844, p1.

- Penzance Gazette, July 24 1844, p3.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4. Without the concerned parties acquiring a private Act of Parliament, divorce was to all intents and purposes impossible in 1820s England. See: Laurence Stone, Road to Divorce: England, 1530-1987, Oxford University Press, 1990, p141-3, 368-82.

- Penzance Gazette, December 13 1843, p3.

- Penzance Gazette, December 13 1843, p3.

- Image from: https://www.amymilnesmith.com/post/paths-to-the-asylum. For more on the Lunacy Commission, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commissioners_in_Lunacy, and I highly recommend Sarah Wise’s Inconvenient People: Lunacy, Liberty and the Mad-Doctors in Victorian England, Vintage Books, 2012.

- Wise, Inconvenient People, xxi.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4, and: https://www.thepeerage.com/p46500.htm#i464996. Winchcombe Hartley died a brigadier in the Punjab: Sun (London), August 26 1858, p8.

- Image from: https://wellcomecollection.org/concepts/uaem25fs#

- Wise, Inconvenient People, chapters 1-3.

- Wise, Inconvenient People, chapter 2. An appendix of this book (p394-400) contains a list of cases they investigated – Mary’s name isn’t amongst them. You can read of Mary’s case in the London Weekly Chronicle, December 10 1843, p3.

- Wise, Inconvenient People, xiii.

- Wise, Inconvenient People, p15.

- Wise, Inconvenient People, p15-16. All the details and quotations of Mary’s and her son’s hearing are, unless otherwise stated, from the Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 15 1843, p4. For more on Barlow, see: http://studymore.org.uk/6bioh.htm#H36

- Image from: https://artmuseum.princeton.edu/collections/objects/37618

- Image from: https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/grosvenor-square

- Wise, Inconvenient People, p160-1.

- Like priest-holes in Warwickshire stately homes, no Cornish mansion is complete without the rumour of a secret tunnel somewhere in its environs. The knee-jerk reaction to their existence is to assume a connection with smuggling in the area. Rosteague, though, must have genuinely had a tunnel at one time. Indeed, another tunnel was discovered at Higher Tregassa Farm near Portscatho in 1908 – this property was part of the Rosteague estate. In 1945, Rosteague’s tunnel was certainly still in existence, though the current owner, Jay Milton, assures me it’s vanished now. She’s conducted a very thorough search of the grounds, but it seems the previous residents of Rosteague, the McKennas, had it blocked up on grounds of safety. See: Cornish Echo, February 14 1908, p8; West Briton, April 23 1945, p2.

- And seven in total: https://www.historyextra.com/period/victorian/queen-victoria-assassination-attempts/

- Image from: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/chm/outreach/trade_in_lunacy/research/womenandmadness/

- St James’s Chronicle, December 12 1843, p2. See William’s baptismal record here: https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=baptisms&id=6249740

- Cornishman, July 5 1894, p6; January 30 1896, p7.

- Cornishman, July 5 1894, p6.

- Cornishman, July 5 1894, p6.

- Information from 1851 and 1861 census, Ancestry Public Member Trees, and: https://www.thepeerage.com/p46500.htm#i464997, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=marriages&id=1929417, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=baptisms&id=6695711, https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=burials&id=4836396

- Cornishman, August 31 1882, p7; July 5 1894, p6.

- Cornishman, August 31 1882, p7.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 21 1871, p6; Ancestry Public Member Trees.

- Cornishman, June 20 1895, p6; August 25 1932, p2.

- Cornishman, August 31 1882, p7.

- Image from: https://www.charlesdickenspage.com/illustrations-web/Bleak-House/Bleak-House-title-page.jpg

- Cornishman, October 10 1907, p3. The valuation of the estates is from Kresen Kernow, ref. FS/3/1548.

- If you really want follow this up, see: Cornishman, June 20 1895, p6; July 8 1895, p5; August 15 1895, p4; January 30 1896, p7; April 9 1896, p2; Cornish Post and Mining News, July 27 1899, p5; Royal Cornwall Gazette, April 12 1900, p7; West Briton, November 7 1900, p3.

- The vault no longer exists; it was demolished in the 1960s to enable the building of the church hall. The Harris coffins are interred under its foundations. With thanks to David Thomas, Churchwarden.

- Cornishman, June 20 1895, p6.

- Cornish Telegraph, April 18 1907, p7.

- From Professor Brown’s in-house guide to Rosewarne, and Cornishman, March 9 1950, p7. James M Holman was a founder-member of Camborne RFC: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/08/26/cambornes-feast-day-rugby/

- From Professor Brown’s in-house guide to Rosewarne, and Cornish Guardian, August 12 1965, p4; West Briton, October 20 1966, p6.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 28 1871, p8.

- For Rosteague’s tunnel, see note 55. Over the years, the old mine workings under Rosewarne have periodically collapsed, giving weight to the stories of old tunnels. Discoveries of waste water pipes in the 1950s and 60s had a similar effect. See: https://www.facebook.com/groups/604486726292230/search/?q=gerry%20treloar

Thanks for all that. Good reading and much to think about!Alan

LikeLike