Reading time: 25 minutes

NOTE: This post contains historically racist language and images that readers may find offensive. Neither the language quoted, or the images shown, represent the views of the author.

I recently watched a powerful documentary on the history of minstrel bands in England. There is perhaps no better place to start this post than by quoting the programme’s narrator, the black actor and activist David Harewood, OBE1:

…in telling this story, we have no choice but to use toxic racial language. In fact, minstrelsy was a major delivery system of it, into British culture.

David Harewood on Blackface: The Hidden History of Minstrelsy, BBC, July 27 2023

It is a great irony, Harewood states, that “an art form that was once mainstream British popular culture”, was also one of its most poisonous.

It’s another great irony that what was once such a common feature of everyday life is now so difficult to study. An example. The BBC’s main Saturday night entertainment from 1958 to 1978 was The Black and White Minstrel Show. It’s stated on Harewood’s documentary that, at its peak, the programme reached 20 million viewers, yet throughout its existence received (justifiable) accusations of racism, from both within the Corporation and without2.

I couldn’t quite believe this tacky, racist trash was still on TV the year I was born. I also couldn’t believe I’d never heard of it – a symptom, it is asserted, of the society I live in:

The destruction of the past, or rather of the social mechanisms that link one’s contemporary experiences to that of earlier generations, is one of the most characteristic and eerie phenomena of the late twentieth century.

Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991, Abacus, 1995, p3

Maybe people don’t want to remember that they watched, and enjoyed The Black and White Minstrel Show (or indeed admit such a thing was ever broadcast to the nation), because nowadays such a thing would be completely beyond the pale of tasteful mainstream television. To be found appreciating a racist TV programme makes its viewer racist in turn.

Now, take the BBC’s current Saturday night flagship show, Strictly Come Dancing, which hit a high of nearly 11 million viewers in 2020, and has also been running for twenty years3. Imagine if, tomorrow, the show was cancelled due to accusations of racism, sexism or whatever, and in over forty years time, had been all-but forgotten in the history of broadcasting? Doesn’t that sound downright weird?

But this process of historical airbrushing occurred with the Minstrel Show, and a good thing too, I hear people cry. But this is precisely the point Harewood makes in his documentary:

The history of blackface minstrelsy is hidden, it has been shelved, and put out of sight, because the subject is too difficult, or too uncomfortable, for people to face.

David Harewood on Blackface: The Hidden History of Minstrelsy, BBC, July 27 2023

Why, you may ask, is someone whose research interests are primarily Cornish history, investigating the murky area of British blackface minstrelsy? I hadn’t intended to. A contact suggested I might like to address the controversy surrounding what is now known as Padstow’s ‘Mummers’ Day’.

This is a Boxing Day tradition until recently known as ‘Darkie Day’. It involves the townspeople parading the streets in fancy dress and/or blackface, singing Cornish folk songs, and collecting money for charity.

(I ought to mention here that the word ‘darkie’ in this context is a contraction of the Cornish dialect word ‘darkening’ which, in Cornish guize or masked dancing, means to darken one’s face, and not as a racist slur.)

As it was called then, Darkie Day fell foul of some unwelcome publicity in 1998. Accusations of racism by an MP led to a police investigation. Besides the obvious target of white people blackening their faces, it’s long been realised that elements of some of the songs sung of Darkie/Mummers’ Day contain lyrics of old minstrel tunes. Apparently such a band was active in Padstow before World War Two, and by some process of social osmosis left their own legacy on the Boxing Day parade. (More on this band later.)

My own work on Mummers’ Day was stillborn. The Cornish academic Merv Davey has produced his own study, and I felt I could add nothing further to it5.

But for me, questions remained. Who was this obscure Padstow minstrel band? Was it the only one of its kind to operate in Cornwall? (The Cornish National Music Archive could provide no answers, and Padstow Museum only hinted at how big a phenomenon minstrel music was.) Could there have been more bands? (As it turned out, there was.) What motivated them to perform? Cultural influences and/or change, cold hard cash, philanthropy, or just the desire to get onstage with your mates and, well, show off? Who were the players – moonlighting pros, or rank amateurs? How popular were they? How did they go down with the punters? Did they use the ‘disguise’ element of minstrelsy to their advantage? When did they fall out of fashion, and why?

The big question: how aware were these bands that their act was communicating a racist stereotype of black people?

To begin to answer this last, we can set up the following conflicting viewpoints. Minstrel bands conveyed

…an idea that black people are either savages in Africa, or they’re happy-go-lucky simpletons in America.

Professor David Olusoga, from David Harewood on Blackface: The Hidden History of Minstrelsy, BBC, July 27 2023

In contrast, one study attempts to

…undercut the tired old story that black-faced minstrelsy is about unrelenting hatred of blacks…for I believe that interpretation to be ahistorical. It ascribes meaning without understanding context…For some…the basic impulse was toward entertainment.

Dale Cockrell, Demons of Disorder: Early Blackfaced Minstrels and Their World, Cambridge University Press, 1997, p162

As we shall see, unwittingly or not, Cornish minstrel bands performed an act that perpetuated grotesque racial stereotypes. In America, at least one contemporary certainly thought as much. W. E. B. Du Bois spoke of the “debasements and imitations”, the theft of black culture, such as

…the Negro ‘minstrel’ songs, many of the ‘gospel’ hymns, and some of the contemporary ‘coon’ songs,—a mass of music in which the novice may easily lose himself and never find the real Negro melodies.

The Souls of Black Folk, 1903, p2096

Yet at the same time, they performed a valuable community function in late 1800s and early 1900s Cornwall.

With that in mind, I realise that I’m writing about an area of Cornish history that, if David Harewood’s previous assertion is correct, people may not want to read. And yes, this post may make you feel uncomfortable. How could it not, when you consider that, in 1931, a journalist for the Cornishman could lament that

One does not see much of the nigger minstrel troupe these days…

December 12, p3

Aren’t such uncomfortable things best left alone? I confess, I came close to not writing this post at all, but surely the historian’s job, however modest they may be, is to inform people of the events of the past, pleasant or not, and attempt to make some sense of them. As one far greater than me bluntly states,

…it really happened…

Richard J. Evans, In Defence of History, new edition, Granta,2000, p253

…so we’d better best get on with it.

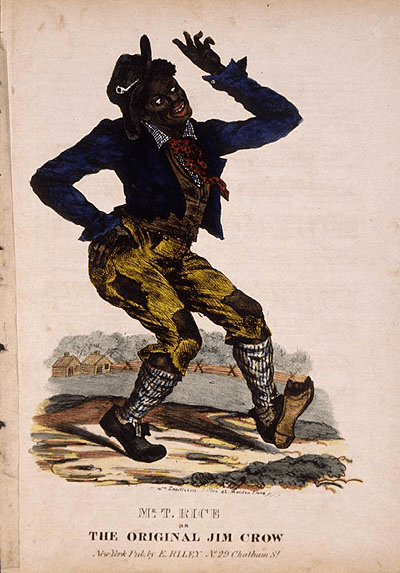

It was the American performer Thomas D. Rice who brought blackface minstrelsy to these shores. He toured his wildly successful act ‘Jump Jim Crow’ in 1836, and by the late 1850s there was at least fifty minstrel troupes in Britain. Even Queen Victoria was a fan8.

This process was not a like-for-like cultural transfer. It couldn’t be, when slavery had been abolished throughout the British Empire in 1834. The USA would not follow suit until 1865, and Britain’s black population was “very few in number”:

The conviction that John Bull was the chosen protector of the slaves was clearly growing in the public mind all through the period from 1830 to 1860…

J. S. Bratton, “English Ethiopians: British Audiences and Black-Face Acts, 1835-1865”, The Yearbook of English Studies 11.2 (1981), p127-42

Britain/England was the land of the free, not America, and minstrel lyrics were altered on British stages to reflect this:

Den I jump aboard de big ship,

And cum across de sea,

And landed in ole England,

Where de nigger be free.

Qtd. from: J. S. Bratton, “English Ethiopians: British Audiences and Black-Face Acts, 1835-1865”, The Yearbook of English Studies 11.2 (1981), p127-42

Free maybe, but still a n_____: slavery might have been abolished, but the language and imagery of racism lingered on. Lest we forget, these were the halcyon days of the British Empire9. Practically anyone not white and bourgeois was an inferior being to be subjugated and controlled. The black man, or a crude parody of him, still danced and sang for the diversion of white people:

…the ideological degradation of the black as socially, culturally and psychologically inferior…worked in concert with the accompanying elevation of…white English civilisation, to confirm, at the other end of the scale, a position of racial superiority and predestined imperiality.

Michael Pickering, “John Bull in Blackface”, Popular Music 16.2 (1997), p181-201

Another reason for the success of British minstrel bands was the public’s desire for alternative forms of entertainment in a newly-urbanised, industrial country:

There is very much the sense of a break occurring at this time with the older, rural cultural forms…

Michael Pickering, “John Bull in Blackface”, Popular Music 16.2 (1997), p181-201

Minstrel bands caught the zeitgeist. Similar happened in Cornwall.

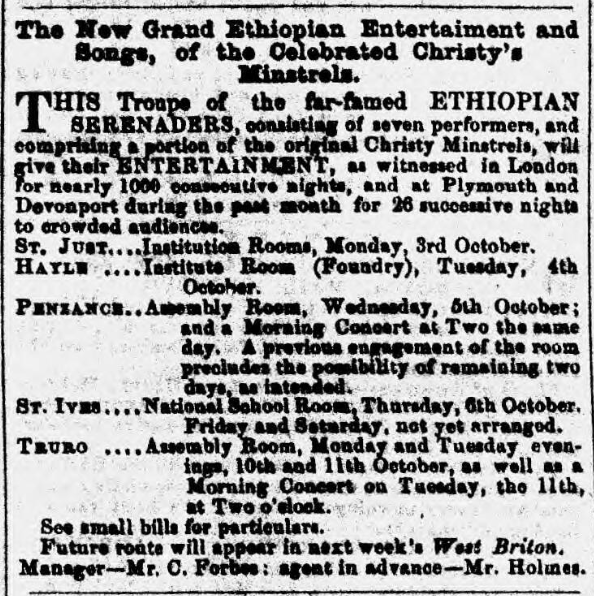

Naval man Henry Rogers noted seeing a minstrel show at Clowance in late 1850 – this is the earliest reference to such an occurrence in Cornwall10. However, it wasn’t until the acclaimed Ethiopian Serenaders (an offshoot of the famous Christy’s Minstrels11) tour in 1859 that the Cornish minstrel craze genuinely took off.

As was later to happen with Padstow’s Mummers’ Day, elements of the latest fad’s songbook rapidly found their way into more established repertoires, as acts looked to cash in. In 1860 the Royal Cornwall Rangers performed in aid of the Bodmin Volunteers, and featured tunes plundered from Christy’s Minstrels12. By 1861, the Wadebridge Volunteers had formed their own minstrel troupe, in an aggressively modern move away from traditional brass band fare.

Others (towns, villages or just groups of musicians) followed suit.

Matthews’ Minstrels were at Hayle in 1872. The Diamond Troupe of Christy Minstrels were at Praze in 1873. The Star Amateur Minstrels played at St Day Town Hall in 1874 and “brought down the house”. Seworgan Prize Band’s performance at Helston in 1877 featured “nigger minstrels”13.

As in England, minstrel bands in Cornwall were prolific throughout the later Victorian era and into the early 1900s. In 1886 alone, there are 14 recorded Cornish shows, from the St Agnes Ebony Minstrels to “Sambo with his banjo” in Ludgvan14.

Note that these are ‘recorded’ instances. It’s a safe assertion that fourteen was the lowest number of minstrel shows taking place in Cornwall for that year. The larger towns would have had a local correspondent, but the newspapers had no designated ‘showbiz’ or ‘entertainment’ columnists yet. For example, the Cornish and Devon Post‘s stringer ‘Mounted Postboy’ was based in Launceston (where the ‘paper was produced), but they were no Nick Ferrari15. We only know that two

…nigger minstrels…

May 8 1886, p2

…performed in the street outside the White Hart Hotel because ‘Postboy’ objected to their obstructing the traffic. As to the contents of the minstrels’ act or how Launceston’s public received them, we can only guess.

Any traces that shows took place further from Cornwall’s urban centres in this era would be lost too, unless a willing local took the time to send a note to the offices of the nearest broadsheet – and said broadsheet deemed it newsworthy enough to run. This is what happened in March 1886, and is why we know the village of St Teath once boasted its own minstrel troupe16.

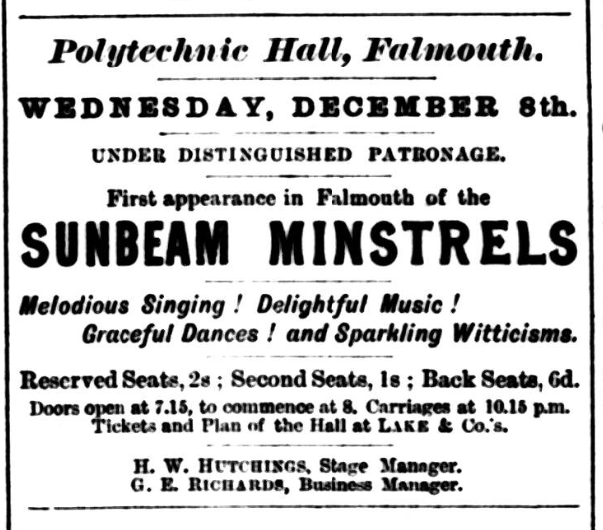

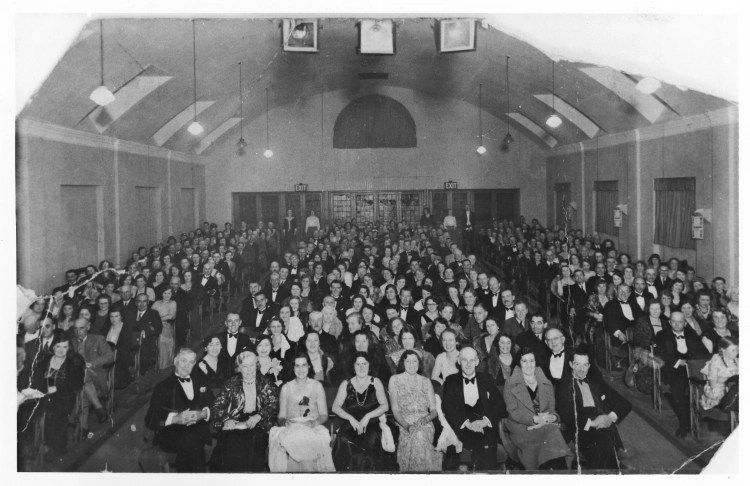

We cannot conclude however that street-shows on the fly, or obscure acts in remoter areas meant that minstrel shows were purely milk for the masses, and that the upper classes still preferred the operas and sonatas on offer in Truro17. Falmouth’s Sunbeam Minstrels were polished and confident enough to hire out the Poly:

A classier minstrel troupe could expect expert guidance. The director of music for the 30-strong Merry Magpie Minstrels of Penzance was George Sellers, a London-born professor of music18.

Cornish minstrel bands, therefore, appealed to a broad swathe of society, were fairly ubiquitous – and successful. The only poorly-attended show I can find owes more to parochialism than a lack of quality on the performers’ part:

(The seemingly inexhaustible examples of Camborne and Redruth’s age-old animosity is becoming something of a running joke in my posts.)

Audiences knew when they were being ripped-off too. A troupe claiming to be the famous Christy’s Minstrels attempted to play at Druid’s Hall, Redruth, in 1871. They drew a bigger crowd than Camborne’s minstrels had back in 1869, but the punters rapidly realised this troupe were a bunch of impostors, with inevitable results:

Somehow or other the troupe cleared their heels without sustaining personal injury, and it is hoped such a lot of nondescripts of the sable order will not again venture to trifle with the temper and forbearance of a Redruth audience.

West Briton, January 26 1871, p5

On the whole, though, minstrel bands met with great success. The Merry Magpie Minstrels’ show at Falmouth Poly

…superadded the charm of burnt cork and lamp black…

Cornish Echo, December 11 1886, p5

The Star Amateur Minstrels of St Day “brought down the house” in Christmas 187419. Ludgvan’s concert in 1886 furnished

…a rich fund of hilarity, without the least scintillation of vulgarity…

Cornish Telegraph, April 29 1886, p5

The Diamond Troupe of Christy Minstrels passed through Praze in 1873, performing “negro melody” to

…a crowded and highly respectable audience.

West Briton, April 10 1873, p3

An all-female troupe toured Cornwall that same year, and a review of their show in Truro noted

…several capital singers…a first class violinist…and the performances throughout are so spirited and superior…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, June 28 1873, p4

From the St Day mining district to genteel Truro, minstrel bands were a hit. A night spent at such a show practically guaranteed a good time. Were it not for the content of these displays, such success would not be so uncomfortable to recall now.

For example, The Merry Magpie Minstrels, though run by a professional director, rejoiced in such stage names as

…’The Golden Cornstalk’…’The Porthminster Coon’…’Our Darkey Dreamer’…

St Ives Weekly Summary, April 17 1914, p2

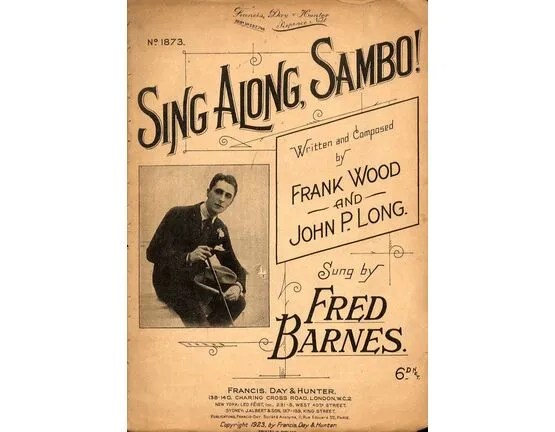

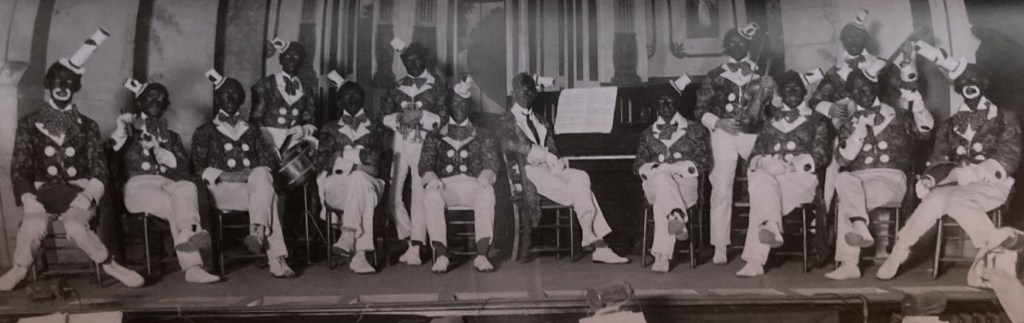

Doubtless these were localised variants of common minstrel characters. There was the dancing simpleton ‘Jim Crow’, and ‘Zip Coon’, a pretentious persona with dandified, chi-chi mannerisms21. They certainly dressed to look the part:

Though the evidence is scanty (reports tend to say how well the minstrels performed, rather than what they performed), the content was undoubtedly racist. When a troupe of twenty in “nigger costume” played at St Ives in 1914, one of the songs in their repertoire was ‘Old Folks at Home’ (more commonly known as ‘Swanee River’), a tune in its then form known to romanticise slavery22.

In 1880 at Truro, the Excelsior Minstrels sung, amongst other staple minstrel hits, ‘Oh! Susanna’, which would have contained something like the following lines:

I’ve come from Alabama, wid my banjo on my knee

I jumped aboard the telegraph, and trabbled down the ribber,

De ‘lectric fluid magnified, and killed five hundred nigger.

Oh! Susanna22

The Excelsiors’ rendering of this song “created roars of laughter”23.

Padstow’s Missouri Minstrels had the following as part of their act in 1930:

We really don’t need to go any further with this to reach the following conclusion: minstrelsy, Cornish minstrelsy, made manifest onstage blacks and black culture as representations that were created and

…pinned down by the sovereign subject. The construction of the subaltern subject in minstrelsy was such that the black as low-Other acquired breath only in the atmosphere of imperial mastery.

Michael Pickering, “John Bull in Blackface”, Popular Music 16.2 (1997), p181-201

The ‘Porthminster Coon’ singing, say, ‘Oh! Susanna’ reinforces white-British superiority at the same time as denying – and denigrating – the very people the entire act lampoons.

Of course, this process probably played itself out unconsciously (which doesn’t make it any less pernicious). It’s possible no Cornish minstrel band set out with the avowed intention of doing any harm, racist or otherwise. As noted earlier, there was little or no coloured population in the country to actively persecute, should they have wished to. In this sense, they (the bands) were as caught up in the cult of imperial mastery as those they impersonated onstage.

And the rise of the British Empire, forged with the Industrial Revolution, made the new entertainment of minstrelsy the success it was in Cornwall. For the Revolution, as we all know, spelt the end for many traditional forms of recreation and community celebrations26.

Progress stops for nobody, and those in control of the wheels of industry frowned upon the activities (which had been largely tolerated in days gone by) of their employees which they perceived as detrimental to production, or profit. For example, it was written of the Helston Feast in September 1886 that the

…excitement, carousing, wrestling and holiday keeping of former days have become obsolete, and a good thing too. Folks in general were attending their business…nothing in particular showed it to be holiday time.

Cornish Telegraph, September 30 1886, p5 (italics mine)

The Mevagissey Feast of 1909 was marred by assaults on policemen and served as further grist to the mill of authority. If there was no feast, there would be no disturbance:

That sort of thing must be stopped.

Cornish Echo, July 9 1909, p7

Of course, you may argue the other way and say that, if there were no policemen present at the Feast, they would not have been assaulted. Mercifully, the Mevagissey Feast has endured27.

Margaret Courtney’s fascinating work Cornish Feasts and Folklore (1890) was perhaps written for precisely this reason: the old ways were dying out. Without her efforts, many aspects of Cornish traditions would be lost for ever.

The pages of her book are littered with such phrases as “was formerly held…” (p4), “has quite died out…” (p7), “formerly practised…” (p9), or “it was customary…” (p16). Nearly everything she records is spoken of in the past tense.

Cornwall’s population needed something new. Minstrel shows, for a time, filled the void.

Yes, they were entertaining; with Cornwall’s new railway system they could reach more destinations and, correspondingly, audiences. Even back in 1859, when the Ethiopian Serenaders sojourned through Cornwall, they played consecutive nights in St Just, Hayle, Penzance, St Ives and Truro28. The age of the train was also the first age of the musical tour, as we would understand it, and we cannot rule out the sheer attraction of being involved in such a novelty for many a budding minstrel.

But the overriding motivation for many a minstrel band to get onstage was, undoubtedly, philanthropic. Two shows in March 1886 illustrate this community spirit. The St Teath Minstrels performed in order to raise funds for the restoration of Delabole Church; the St Agnes Ebony Minstrels raised £7 (£770 today) for the Cornwall Royal Infirmary29.

The Excelsior Minstrels were at Truro in 1880 to generate cash toward the purchase of a new organ for St Paul’s Church. In 1919 the catchily named Holman Number 3 Works Minstrel Troupe from Camborne raised £90 (£3900 in 2024) for St John’s Ambulance30.

Padstow’s Missouri Minstrels avowed mission statement was that all performances

…have been and will be given in aid of deserving charities, the Minstrels only getting their travel expenses…

Cornish Guardian, September 25 1930, p15

When top of the bill at the (long demolished) Cosy Nook in Newquay, the Missouri Minstrels gave the proceeds to the Newquay School of Physical Culture and Gymnasium Club31.

Earlier that year, the Missouris had donated their takings from a show in their hometown to the coffers of Pendeen Church33. Here’s the original poster:

Although the evidence is once more depressingly spartan, we can suggest that Cornish minstrelsy filled another void left by the erosion of feast day customs, and this is to do with the carnivalesque:

The temporary suspension, both ideal and real, of hierarchical rank created during carnival time a special type of communication impossible during everyday life…[which was] liberating from norms of etiquette and decency imposed at other times.

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, Indiana University Press, 1984, p10

As a community’s safety-valve, a carnival-like event could reverse roles and upend hierarchies. For a brief time, the world was turned upside-down. Thus it was at Camborne’s Carnival in 1888, James M. Holman, scion of the engineering dynasty (and its head from 1908), JP for Cornwall and mining-school governor, could be witnessed wearing blackface as a member of a “nigger group”35. A figure synonymous with Cornwall’s industrial might, for one day, cast himself in the role of civilisation’s (literally) dark Other.

This social inversion cut both ways. As carnivals and feasts came under threat, the blackface personas prevalent in minstrel troupes gave those people under the mask a freedom they lacked in their everyday lives. Helston’s Hal-an Tow, which traditionally presented that town’s working-class population with a chance to “subvert the natural order…and claim power for the day”36 by wearing masks and flirting with each other in the woods, had fallen into disrepute by the late 1800s. Minstrelsy presented the opportunity to wear another mask. As one critic has asked,

Why not don the attire of a coalminer or pit lassie, whose faces after work somewhat resembled those to which burnt cork had been applied?

Michael Pickering, “John Bull in Blackface”, Popular Music 16.2 (1997), p181-201

The answer is because these people hadn’t the same social licence (or audience) that a minstrel perhaps had. Coalminers and pit lassies (or, considering Cornwall, tinners and bal maidens), although the underclass, were still very much part of liberal-bourgeois society. The minstrel-as-Other, by contrast, represented a figure who wasn’t part of the social structure at all, or certainly didn’t count enough to be recognised as such: they merely existed onstage. This outsider position allowed those playing minstrels the opportunity to comment on and criticise the society which they, in their everyday lives, were part of.

In other words, a poor undernourished miner could become the ‘Porthminster Coon’ and arm himself with the freedom to speak his mind, before a paying audience.

James M. Holman’s brief cameo aside, what we know of the minstrels’ lives suggests they were predominantly working-class.

Banjo player George Thomas of Camborne was a plumber. Ted Rogers, another Camborne man, was a cabinet maker. James Pillage of Michaelstow was a gardener. Thomas Cleave of Egloshayle was a mason37.

Considering Padstow’s Missouri Minstrels, Dennis O’Keeffe was a shipwright (as well as a coastguard, a Naval Petty Officer in the War, and Vice President of Padstow’s British Legion), Archie Gard was a fish merchant, and Joseph Apps a ploughman38.

Ordinary working men by day, but as dusk fell, they were

…a new breed of adventurers, urban adventurers who drifted out at night with a black man’s code to fit their facts.

Norman Mailer, The White Negro, 195739

In 1930 at St Merryn, O’Keeffe performed a “topical song” which earned an encore40. Frustratingly, we are not told what issues he commented on. He took the same opportunity to sing his mind in 193141.

An earlier Padstow troupe performed as part of the celebrations of the Relief of Ladysmith during the Boer War in 1900:

Many of the quips and comicalities were decidedly original, and were, especially those which referred to local affairs and celebrities, much enjoyed.

Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 8 1900, p342

Would working men publicly mock their betters under normal circumstances, and be applauded for it?

Launceston’s newshound ‘Mounted Postboy’, who in 1886 objected in print to a minstrel duo blocking the street with their act (see above), also wondered

Would the Salvation Army be allowed equal freedom?

Cornish and Devon Post, May 8 1886, p2 (italics mine)

A rhetorical question, but the point is clear: normal social relations were temporarily suspended whenever, and wherever, a minstrel troupe performed.

Although sporadic performances by minstrel bands continued until the Civil Rights Movement gathered pace in the 1960s43, the brief appearance in the 1930s of the Missouri Minstrels was the act’s last hurrah in Cornwall. Several factors contributed to its demise.

The first was World War One, which, wrote A. L. Rowse,

…swept away the old landmarks in a tide of change.

A Cornish Childhood, Truran, 2010, p444

Though not exactly ‘old’, minstrelsy was, by 1919, thought to be on the wax and wane. When the Holmans Troupe visited Newquay, a columnist hoped that

…the old minstrel show is by no means played out yet…

Cornish Guardian, August 29 1919, p7

The journalist was wrong. When the Missouri Minstrels hit Bodmin in 1931, it was noted that such an act hadn’t performed in the town for years45. Indeed, when the Missouris’ driving force, Dennis O’Keeffe, died in early 1935, the troupe appears to have broken up46.

The war also swept away a great deal of a more ancient Cornish landmark: mining. Cornwall had weathered slumps before, but this felt final. By 1921, there was 3,000 unemployed miners west of the Tamar, with men emigrating by the hundred47.

The Industrial Revolution, which in Cornwall had trampled all over so many ancient ways of life, looked to be over too. It’s little surprise many were unsure what the future held:

I have tramped this road daily for more than thirty years, and now I am doing it for the last time…God knows whether I shall have dinner next Sunday…

a soon-to-be out of work miner, Cornishman, June 30 1920, p5

Some concluded that the only way forward was to get things back to how they had once been – or at the very least recreate an idealised version of the past. The Old Cornwall Society was formed in 1920 and sought to deliver on the following manifesto:

…to try to rouse the interest of the young people in the old dialect, customs, beliefs, and spirit of Cornwall before these things have become utterly a thing of the past.

Cornishman, April 28 1920, p6

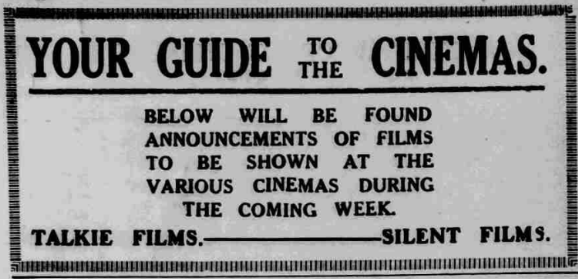

Helston’s Hal-an-Tow, for example, was proudly resurrected in the 1930s48. I doubt they even reached the debating table, but the social retention/revival of minstrel bands was clearly not on the Society’s agenda. Too American, too British, and too modern. Plus, by the 1930s, a new form of entertainment could replace many of the minstrels’ functions.

Cinema was the new thing on the block, and if you wanted a taste of minstrelsy, well, many a feature of the 1930s included a professionally choreographed routine. The 1934 film Kid Millions, shown in picture houses across Cornwall in 1936, for example49. Likewise the Fred Astaire/Ginger Rogers vehicle Swing Time (1936), which you could see at the Cape Cinema, St Just50.

A year before she realised she wasn’t in Kansas anymore, Judy Garland starred in Everybody Sing, which was shown at the St Austell Odeon51. The Wikipedia entry for the film fails to mention that the girl who would be Dorothy appears on the screen in blackface:

It’s oddly fitting that, on the same newspaper page that carried one-time Missouri Minstrel and philanthropist Dennis O’Keefe’s obituary, there is an advertisement for a cinematography show in Foxhole. All proceeds were to go to charity52.

Moving pictures had superseded the stage.

In theatres, town halls and church rooms, the once eagerly-anticipated appearance of a Cornish minstrel band had become a thing of the past.

Thankfully, we will never see their like again.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Harewood, whose ancestors were slaves on a Barbadian plantation, is a passionate advocate of having the British government apologise for its involvement in the slave trade. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Harewood

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Black_and_White_Minstrel_Show

- See: https://www.radiotimes.com/tv/entertainment/strictly-come-dancing-2024-ratings-newsupdate/ , and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strictly_Come_Dancing

- Image from: https://www.cornwalllive.com/news/cornwall-news/cornwalls-controversial-festival-once-known-2321390

- See: Guizing: Ancient Traditions and Modern Sensitivities, by Merv Davey, 2006. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/1786363/Guizing_ancient_traditions_and_modern_sensitivities . That some of the songs sung on Mummers’ Day contain racially offensive words is noted here: https://www.padstowmuseum.co.uk/mummers.html . Mummers’ Day has also been the subject of a Radio 4 broadcast, and work by an independent filmmaker. See: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2rLzDFR653mHgzFzXKpfpDB/harmless-tradition

- Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/408/408-h/408-h.htm

- Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_D._Rice

- See: Richard Waterhouse, “The Internationalisation of American Popular Culture in the Nineteenth Century: The Case of the Minstrel Show”, Australasian Journal of American Studies 4.1 (1985), p1-11.

- For those wanting further confirmation of this, see: Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire 1875-1914, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987.

- Kresen Kernow, ref. EN2626.

- For more on Christy’s Minstrels, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christy%27s_Minstrels

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, June 8 1860, p5.

- West Briton, December 2 1872, p3, and April 10 1873, p3; Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 2 1875, p5, and January 4, 1878, p7.

- Cornishman, March 18 1886, p7; Cornish Telegraph, April 29 1886, p5.

- Before bringing topless darts to our screens, Ferrari cut his journalism teeth as a showbiz reporter for The Sun and edited its ‘Bizarre’ gossip column in the 1980s. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nick_Ferrari

- Cornish and Devon Post, March 6 1886, p4.

- As surveyed in Petroc Trelawny’s Trelawny’s Cornwall: A Journey Through Western Lands, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2024, p249-54.

- Cornishman, December 5 1901, p8, Cornish Telegraph, December 11 1901, p6, 1901 census.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 2 1875, p5.

- Image from: Michael Pickering, “John Bull in Blackface”, Popular Music 16.2 (1997), p181-201.

- See: Richard Waterhouse, “The Internationalisation of American Popular Culture in the Nineteenth Century: The Case of the Minstrel Show”, Australasian Journal of American Studies 4.1 (1985), p1-11.

- St Ives Weekly Summary, April 17 1914, p2, and: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Old_Folks_at_Home

- Lyrics from: https://songofamerica.net/song/oh-susanna/

- West Briton, February 12 1880, p5.

- Image from: https://www.sheetmusicwarehouse.co.uk/20th-century-songs-s/sing-along-sambo-song-featuring-fred-barnes-1/

- I recommend the following on the Industrial Revolution: Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution 1789-1848, Abacus, 1977; and Robert C. Allen, The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective, Cambridge University Press, 2009. For the demise of many Cornish customs, see: A. K. Hamilton Jenkin’s The Cornish Miner, 3rd ed., George, Allen and Unwin, 1962, p288-98.

- See: https://www.mevagisseyfeastweek.org.uk/about/history/

- West Briton, September 30 1859, p1.

- Cornish and Devon Post, March 6 1886, p4; Cornishman, March 18 1886, p7, and April 1 1886, p6.

- West Briton, February 12 1880, p5; Cornishman, December 2 1919, p7.

- Newquay Express, May 1 1930, p4.

- Image from: https://reconnectcornwall.wordpress.com/2013/02/21/coming-to-newquay-11th-18th-april/

- Newquay Express, February 20 1930, p12.

- Image purchased and downloaded from: https://www.alamy.com/stock-photo-antique-missouri-minstrel-poster-padstow-cornwall-england-uk-europe-12130867.html , January 17 2025.

- Cornishman, September 20 1888, p7. For more on Holman, see: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/08/26/cambornes-feast-day-rugby/

- For Hal-an-Tow, see Petroc Trelawny’s Trelawny’s Cornwall: A Journey Through Western Lands, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2024, p110-11.

- For Thomas, see the 1921 census and: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/09/21/the-magnificent-seven-meet-the-invincibles/ . For Rogers, see the 1901 census and the Cornishman, July 18 1901, p2. For Pillage, see the 1901 census and the Cornish Guardian, December 27 1901, p5. For Thomas Cleave, see the 1861 census and the West Briton, August 2 1861, p5.

- O’Keefe was obviously popular in Padstow; his obituary is in the Newquay Express, January 17 1935, p8. See the 1921 census, and the Cornish Guardian, October 30 1930, p3.

- Available at: https://www.dissentmagazine.org/online_articles/the-white-negro-fall-1957/

- Newquay Express, November 27 1930, p12.

- Cornish Guardian, January 15 1931, p4.

- For more on the Relief of Ladysmith, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relief_of_Ladysmith

- One of the last was given by the St Columb Church Guild Group in 1966. See: Cornish Guardian, August 11 1966, p5.

- For more on this catastrophic historical fissure, see: Eric Hobsbawm, Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, 1914-1991, Abacus, 1995, p1-54.

- Cornish Guardian, February 5 1931, p2

- Newquay Express, January 17 1935, p8, carries O’Keefe’s obituary.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, June 29 1921, 5; Cornubian and Redruth Times, October 20 1921, p6.

- See Petroc Trelawny’s Trelawny’s Cornwall: A Journey Through Western Lands, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2024, p110-11.

- Cornish Guardian, March 19 1936, p3, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kid_Millions

- Cornishman, July 8 1937, p5, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swing_Time_(film)

- Cornish Guardian, October 13 1938, p15.

- Newquay Express, January 17 1935, p8.

Hah, a trigger warning. I love these.There was one on a Netflix thing I was watching that warned we might see alcohol consumed.

Interestingly, when I was at Radio Cornwall I interviewed the then Labour MP, Bernie Grant, about Darkie Day in Padstow. I think he had written a piece in one of the national newspapers complaining about it. I did point out to him that it was a pagan festival that went back generations, and the purpose of blackening their faces was to avoid the participants being recognised if they indulged in wild behaviour or begged on the streets. It was something that happened up and down the country at the Winter Solstice.

Of course, he’d already decided it was a racist event so he wasn’t interested. I also remember that Diane Abbot put forward a motion in the House of Commons to have it banned.

We need to have a chat at some stage. As the Spring approaches I’m thinking about the next book

>

LikeLike