Reading time: 25 minutes

…there were always people who were responsible. The bad guys. ~ Stieg Larsson1

The Napoleonic Wars created shortages of practically everything in Britain. As victory on the Peninsula looked increasingly certain, the financial consequences of a wartime economy looked equally dire. Luxury goods were at never-before-seen premiums (which resulted in a late flourish for smuggling), as were the everyday essentials. Arguably the pinch was felt most here regarding wheat, flour and bread2. When bread was available, it was of dubious quality and origin:

There is at present scarcely a white loaf to be bought in London, half of which does not consist of the very worst foreign and heated flour mixed up with…other ingredients, to make it please the eye.

British Mercury, September 18 1811, p2 (emphasis mine)

Part of the problem was that the British people, on the main, preferred white bread. Healthier brown, wholemeal and coarser-grained loaves were the traditional foodstuff of labourers, peasants, the dirt-poor, and even horses3.

This stubborn – and erroneous – insistence that white bread is the best bread reached its apogee in the early 1900s with the advent of the mass-produced sliced white. A sliced brown loaf was a non-starter, and from this we may deduce that the general public took a lot of convincing that brown bread is better for you. In 1847, another time of dearth, the British people were exhorted to see the error of their ways and buy wholemeal4:

…it is known by men of science that the bread of unrefined flour will sustain life, while that made with the refined will not.

The Leamington Spa Courier quotes from the Monthly Journal of Medical Science, February 13 1847, p4

The whiter and finer the flour, the less healthy it is. Men of science might have known this, but they were largely ignored. Thus, when the wholemeal National Loaf replaced the ubiquitous white in 1942, it was met with popular opposition:

…the public has consistently turned a deaf ear to all arguments and allurements.

West Briton, April 16 1942, p45

In the final years of the Napoleonic Wars, however, no voices of officialdom or science appear to have preached the benefits of wholemeal flour to a predominantly disdainful – and snobbish – public. White was best, and the whiter, more refined, the flour, the better. The purer.

White flour, though, was relatively scarce, and therefore expensive; but even money-saving tips downplayed the wholemeal option. One newspaper recommended adding boiled rice to your dough. This produced a loaf that was

…very palatable, and lighter and whiter than wheaten bread.

Pilot (London), November 8 1811, p3 (emphasis mine)

In purely economic terms, the demand was for white bread, but supply couldn’t keep up with this demand. This created a gap in the market. Some merchants, millers and bakers realised this, and took steps to fill the gap.

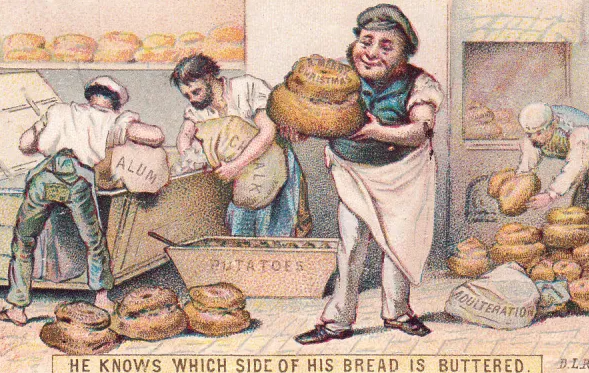

Unscrupulous steps. Refined white flour was expensive. The solution was to mix the flour with another white substance. Said substance would be cheaper to buy and more readily available than flour, and also denser. (If it made your flour whiter too, that was an added bonus.) Any loaves baked could then be sold on to unwitting shoppers for the stipulated price, at the stipulated weight. This practice was as dishonest as it was illegal.

The production of bread was heavily regulated (after all, the health of the nation was at stake), but the strain of the War perhaps led to a lowering of watchfulness. For example, the medieval Bread and Ale Assizes had fallen into desuetude by the early 1800s. Furthermore, the Making of Bread Act (1757), introduced to punish those who sought to further ‘purify’ flour by adding whiteners such as alum (a compound of aluminium and potassium), failed to perturb any rogue baker during the period of our concern7.

In May 1811 the Liverpool Militia bridled at a batch of bad bread that had been consigned to them. Their superiors’ solution was to flog a private for insubordination9.

In 1813 an Oxford baker was caught making loaves from flour mixed with alum and potatoes. He used this method, he claimed, for

…the purpose of improving the flavour of the bread.

Oxford University and City Herald, October 2 1813, p4

In October of that year another baker in Greenwich was fined for combining his flour with a “Derbyshire stone” which he had burnt and then ground10. That same month, inspectors raided a baker’s shop in Clerkenwell and discovered a bathtub full of mashed potato, ready to be mixed with a batch of dough. Another was caught employing the same technique over Christmas11.

The situation was bad enough for flour merchants to publicly reassure buyers as to the purity of their flour, and the honesty of their trade. A Birmingham businessman took just this course of action in April 181312.

It was realised that the cost of flour wasn’t rising as fast as other foodstuffs because, due to adulteration practices, less was being sold. The use of potatoes had

…become so prevalent as to over balance the extra consumption…Three years back…Potatoes were frequently hardly saleable; whereas the quantities bought up these last two winters, for the avowed use of adulterating bread, have been immense.

Evans and Ruffy’s Farmer’s Journal, April 18 1814, p1

Leaving the obvious dishonesty aside, a loaf of bread part of which contained potato wasn’t all bad. The buyer may have been duped, but at least they were getting some nutrition. Cutting the flour with alum, say, or ‘Derbyshire’ stone however was downright dangerous, and concerned newspapers sought to inform their readers how to identify an adulterated loaf13.

There was one fail-safe way to conclude that you’d been sold a spiked loaf: it made you ill. As one food historian has observed, if a miller sold a baker adulterated flour, which was in turn adulterated further by the baker himself, there could be serious consequences:

If you were a worker eating 2lbs of bread a day and not much else, when you consider that a third of what you’re eating won’t benefit you at all, you can see why chronic malnutrition is such an issue. And when your adulterants are things like plaster of Paris and alum, you can also see why chronic gastritis [an inflamed stomach caused by excessive intake of acid] is a problem…you’re going to start off with constipation, then…irregular bowel movements, and that will lead to chronic diarrhoea…in workhouse children, that will lead to death15.

The whitest flour and the whitest loaf could ironically have been the purest poison. To be sure, the bakers mentioned above were, in criminal terms, small fry. Their cottage industries of adulteration, though despicable, would only affect people in their immediate vicinity.

One group of men, though, had the raw materials, financial wherewithal, network, greed and total lack of morality to, where adulterating flour was concerned, think big. They turned a grubby backstreet act of swindling into a full-scale operation.

And they were Cornish.

James Osler and William Trahar were prosperous Truro businessmen, Osler being described as a grocer. Trahar was a flour merchant at one of Truro’s more desirable locations: the newly-developed and quintessentially Georgian Lemon Street. For reasons already discussed, Trahar may have been struggling financially: in early 1813 he was auctioning off land for rent. He also turned to more dubious business practices. Back in 1811, a Scorrier man had issued copper trade tokens or ‘Cornish pennies’ for exchange; Trahar had produced his own cheap counterfeits with a view to ripping off his competitor17.

Much of Osler and Trahar’s collateral, though, was tied up in their mills: Osler owned one at Penweathers, Traher’s had his at nearby Treyew (both are long-vanished). Judging by the plan both men seem to have concocted around 1812, the mills weren’t generating much income: maybe local grain crops were of a quality too inferior to compete with finer produce elsewhere19.

Whatever the reason, Osler and Traher were conscious of the necessity to produce the finest, whitest flour they possibly could – it’s what the public wanted. They were obviously prepared to do this by any means possible. And that meant adulterating their flour, which in turn meant breaking the law and endangering public health.

So be it. Question was, what to adulterate their flour with? They needed something cheap, denser than the product they were claiming to sell, readily available nearby, and with a seemingly inexhaustible supply. Oh – and it had to make their flour whiter too. Such additives as alum and plaster of Paris were, for Cornwall, out of the question. The transport overheads and attendant hassle would not be easily overcome. That old standby, the humble potato, doesn’t appear to have been considered either20. Then either Osler or Trahar had a brainwave:

What about china clay? It ticked all their immoral boxes.

For all their crookedness, Osler and Trahar were men of their times: venture capitalists of the Industrial Revolution. They sought to buy, and produce, an item in the cheapest market, and sell it in the dearest. China clay (cheap) would become refined white flour (dear).

They also appreciated the need to incorporate others into their scheme, create a convincing cover-story, and (as much as possible), stay in the background.

A Redruth haulage firm, Trenerry & Co., were sent to the china clay works at St Stephen-in-Brannel. There, they bought a quantity of clay, ostensibly for transport to a pottery on the Isles of Scilly. Of course, no such business existed, but a credible reason for buying up large amounts was required, as was a fictional location that was difficult to check. Osler and Trahar were not spending pennies on a hundredweight of clay here and there21.

No. Trenerry & Co. must have presented a vast order at St Stephen. From 1812 to 1814, it was estimated that two hundred tons of china clay had been

…vended to the public…

Taunton Courier, May 19 1814, p7

…under the guise of flour from the mills of Osler and Trahar.

Though cheap, buying two hundred tons of clay was a considerable outlay. It retailed at £6/ton, so Osler and Trahar invested £1,200 in the raw materials. That’s £80,900 today23.

They must have been confident in the success of their scheme.

Trenerry & Co. never took the clay to the Scillies. It was transported straight to the mills at Penweathers and Treyew. In other words, Trenerry was in the know, and they were probably paid off. After what must have been a big first shipment, Osler and Trahar decided to keep this part of the operation in-house. One of Trahar’s employees, James Rowe, and a servant of Osler’s were charged with the cross-country clay run24.

The businessmen also desired to (literally and figuratively) keep their hands clean of the adulteration process at their mills. From Christmas 1813 (or so he would later claim), Trahar let his mill, Treyew, to John Rowe, the brother of James. Osler went a degree further in cunning. His front-man at Penweathers was Henry Rundle; he claimed to be renting the mill from a shadowy Mr Dunstone – maybe Osler had sub-let Penweathers to this man. Either way, both Osler and Trahar now had ‘cut-outs’ in place, and the whole operation could proceed25.

The refined clay brought from St Stephen was described as having

…in appearance the finest hair powder, [and] is quite soft to the touch…It improves the appearance of the flour with which it is mixed in a considerable degree, so that persons, not aware of the cheat, would prefer it to that which is pure.

Taunton Courier, May 19 1814, p7

Just how much clay was being mixed into the flour varied. The “villains concerned”, one report ran,

…finding the imposition pass so readily, gradually increased the quantity…until at length one fifth, and sometimes one fourth, of the whole was clay.

Taunton Courier, May 19 1814, p7

It was also noted that two quarts of adulterated flour weighed as much as three quarts of normal, uncontaminated flour. A Falmouth physician later analysed samples of flour that had been sold to the people of the town. One contained one-ninth of clay, the other was wholly clay27.

(As we shall see, Osler and Trahar would ultimately make the outrageous decision to completely abandon the notion of cutting flour with clay, and just sell the clay…as flour.)

The ever-increasing confidence and recklessness of the perpetrators goes some way to explaining the varying amounts of clay found in their flour, but the haphazard preparation methods must also have been a contributory factor. John Holman, an employee at Treyew, would later describe mixing heaps of “whiter” flour and a duller variety with a spade. He also saw John Rowe empty “four or five” peck tubs (a peck was around 9 litres) of “white stuff” into the six gallon tub of flour that he was mixing28.

Clearly, precision was not the order of the day, and ingesting clay in any great amount is far from advisable:

When taken by mouth: Clay is POSSIBLY SAFE when taken by mouth for a short period of time. It has been safely used in doses up to 3 grams daily for 3 months or 4 grams daily for 6 weeks. Side effects are usually mild but may include constipation, vomiting, or diarrhea. Clay is POSSIBLY UNSAFE when taken by mouth for a long period of time. Eating clay long-term can cause low levels of potassium and iron. It might also cause lead poisoning, muscle weakness, intestinal blockage, skin sores, or breathing problems.

The ill-effects of imbibing clay were also realised at the time:

Upon the clay no acid will operate, consequently it resists all the powers of the juices of the stomach, and must have had the most serious effects upon the health of those who were in the general habit of using this pernicious mixture.

Taunton Courier, May 19 1814, p7

In short, eating clay makes you constipated.

Mary Arthur of Falmouth baked a loaf from Trahar’s flour, which failed to rise. Her entire family objected to it, and she herself

…found that it lay hard on her stomach and made her ill.

West Briton, August 23 1816, p3

This came from a bag purported to be “the best” at Treyew mill – one dreads to think what ‘the worst’ was like. The Falmouth shopkeeper who purchased it, and sold some to Arthur, correspondingly paid “the best price” for it29.

What we must understand is that Mary Arthur was perhaps merely one of dozens, hundreds, even thousands who fell foul of Osler and Trahar’s activities. As I remarked earlier, both men thought big. The extent of their operation, and their arrogance, is breathtaking.

On May 2 1814 the sloop Diligence, skippered by a Thomas Chapman, was impounded at Plymouth and searched. It had sailed from Truro. The sixty-four sacks of “fine” flour in her hold turned out to be anything but. Twenty-four sacks (some of which had already left the port), contained a mixture of flour and clay, and were for Mr W. Smith of Plymouth. They had been sent from Osler. The other forty, though shipped by John Rowe of Treyew, had been sold by Trahar and were for Mr John Bartlett of the nearby Widey Mills. These sacks

…consisted entirely of pulverized china clay, resembling flour of the best quality.

Taunton Courier, May 26 1814, p5

The Diligence had a deadly cargo.

The authorities must have been distressed to discover several other sacks of ‘flour’, via Osler at Penweathers, had arrived in the city some 6 to 8 weeks previously. Then, on May 14, the local magistrates busted a baker on Market Street by the name of Potter. He was in possession of thirty-six sacks of Osler and Trahar’s adulterated flour, and was viewed to be

…knowingly concerned in this shameful imposition.

Taunton Courier, May 26 1814, p5

Therefore, the question we have to ask is, how much adulterated flour (or pure, unadulterated clay) did Osler and Traher manage to ship out of Truro? There may have been more vessels, and other ports, but we only know for certain that the Diligence, with Chapman (who of course would claim ignorance at the contents of the sacks), sailed the flour from Truro to Plymouth.

If the two-year lifespan of the operation is accurate, the Diligence made the journey from Truro to Plymouth on ten other occasions31.

Let’s assume the Diligence carried the adulterated flour on each voyage, and also assume that sixty-four sacks was the normal amount shipped. Each sack would have been the regulation weight, 280lbs, so sixty-four sacks would have been 17,920lbs.

That’s around 8 tons of clay/flour. So, for the ten shipments Diligence made prior to discovery, we can posit that 80 tons of Osler and Trahar’s poisonous substance was sent to Plymouth alone.

If that isn’t frightening enough, remember that Osler and Trahar purchased at least two hundred tons of clay from St Stephen-in-Brannel. They must have had other outlets. We’ve already observed how their flour appeared in Falmouth; three more sacks were located in Flushing and unceremoniously dumped in the sea32.

The compound was also delivered to

…all neighbouring mines.

West Briton, May 13 1814, p2

Indeed, the Adventurers of Wheal Unity near St Day clubbed together a £50 (£3,300 today) reward for anyone who could put the finger on the men who made their workforce ill33.

Stories abounded that the contaminated flour had been sold to the Army on the Peninsula, to the Royal Navy, and to the PoW prison at Dartmoor34.

(Over time, these tales have grown with the telling. I can find no further contemporary evidence to confirm much later reports of the Wheal Kitty Adventurers at St Agnes offering a similar reward as their counterparts at St Day, or that the flour turned up at the RN depot at Deptford, or the Army stores in Spain. Of course, it could have happened; at least one baker, a Portsmouth man, was convicted of selling adulterated flour to Dartmoor Prison. Alas, we aren’t told what the flour had been cut with35.)

If true, Osler and Trahar were war profiteers, as well as criminals. Clearly people championed white flour in peacetime as well as periods of conflict, but the Napoleonic Wars probably presented them with another market to exploit.

And the money rolled in. It was estimated that Osler and Trahar made between £4-5K from their adulterated flour. In 2024, that would be a return of between £269,900 and £337,000. Even when you account for the overheads (labour, transport, shipping, raw materials, bribes etc), you’re still looking at a massive profit36.

All this is easily calculable. What is impossible to measure, is how many people and families in Cornwall, Devon, possibly the entire South West region, were affected. How many were made ill? How many suffered malnutrition? How many lost their jobs as a result, their income, their homes? How many wasted away and died?

All the while, Osler and Trahar gave the appearance of gentlemen. Both donated to a public subscription to provide aid for a German population much distressed by the War. Which, when you think about it, is rather ironic38.

It must have been beautiful. But it couldn’t last. It didn’t last. Osler and Trahar, in the end, were undone by their own stupendous greed. Trahar appears to have had to step in on several occasions to reduce the cost of flour sold by his man Rowe after complaints were made about its quality. Also, the public by now had been well educated on how to detect a suspect loaf – and Trahar’s must have been suspect. Indeed, people later remarked that they had never seen

…flour like it…

West Briton, August 23 1816, p3

…much less want to eat it. Eyebrows would have been raised, questions would have been asked. Suddenly, the heat was on. Although in two years the Diligence made ten trips to Plymouth before the fateful final voyage, five of those took place between September 1813 and March 1814. Osler and Trahar must have been rapidly selling off the evidence39.

Every good crime story needs a grass, and this one has it. We are never told who tipped the wink to the Truro magistrates, but a strong candidate has to be John Osborne, a local carter. He had already intimated to Rundle at Penweathers that he would blow the whole gaffe, and had been strongly discouraged from this course of action by the Rowe boys. Osborne had once been part of the transport leg of the operation, but wasn’t to be trusted. As a precaution, Penweathers received no further deliveries of clay for six months41.

Nevertheless, on April 28, 1814, two constables, Edward Clemence, Richard Brown, plus a surly bunch of locals raided Penweathers and Treyew. The former, with Henry Rundle present, contained a small amount of adulterated flour. Rundle, like all good (and well paid) front men, stated that he rented the mill off a Mr Dunstone, and that Osler had only ever asked him to grind clay, never flour.

John Osborne, though, gave the authorities the link between Osler, Trahar and the adulterated flour trafficking ring. It was he who said that Osler’s servant had been on the clay run with James Rowe, who was of course linked to Treyew through his brother42.

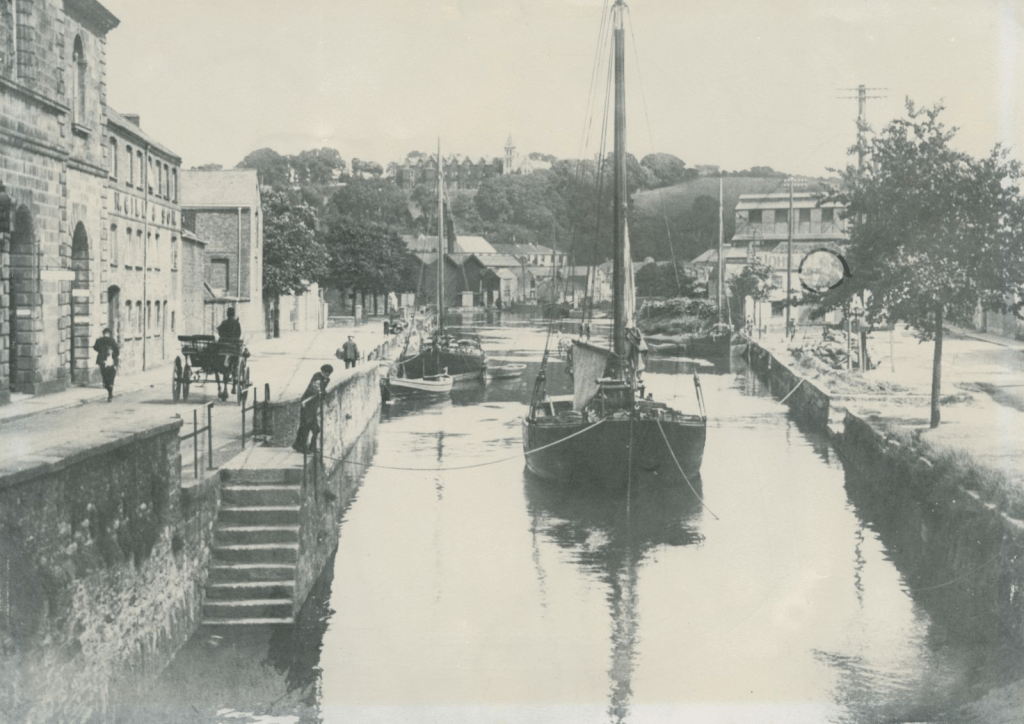

At Treyew, John Rowe was caught bang to rights. Over a dozen sacks of adulterated flour were discovered, ready for sale. In another room was around two tons of fine clay, all of which was later slung over the side of Lemon Quay. Cross-examined, Rowe played his part. The clay and flour were his property. He was renting the mill for his business from Trahar. He had never mixed clay with flour. The clay was only there for sale. He couldn’t remember who he’d sold the clay to, or for what purpose. In fact, he couldn’t remember who he’d bought the clay off in the first place, Your Honour…43

Rowe and Rundle were each fined £10 (£670 today). The magistrates expressed

…their regret that the law did not allow them to inflict a punishment more proportionate to the enormity of the offence…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 7 1814, p2

The Press also harboured suspicions that the two men were

…by no means the principals in this nefarious transaction.

Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 7 1814, p2

Who were the real bad guys? Equally pressingly, how much adulterated flour had already left Truro? With as much urgency as they could muster, revenue officers followed the trail all the way to the Diligence, which had recently sailed for Plymouth.

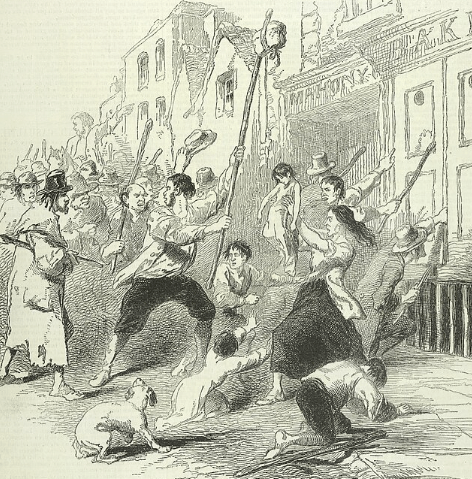

Before Osler and Trahar could be (hopefully) brought to book, there was an outcry, and the public believed they knew who the culprits were. On Wednesday May 11 two effigies were paraded and burnt on the streets of Truro. Though unidentified, the figures represented

…two persons supposed to be no strangers…

West Briton, May 13 1814, p2

…to the events. One imagines Osler and Trahar kept their curtains drawn that day. Besides the bounty posted by Wheal Unity, a dozen Cornish flour merchants offered their own cash reward, as well as professing their non-involvement in such practices44.

(Only the Truro constable, Richard Brown, ever received a reward. He blew his £5 on the public rejoicings at the end of the War45.)

One broadsheet described the trafficking as “beyond belief”46, while another waxed lyrical on the

…abominable composition by which the health, if not the lives, of so many people have been put in jeopardy…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 14 1814, p2

In London, one journalist blithely wondered if it would

…not be a great improvement of this system to send the clay to market in balls ready for eating, which would save the expense of baking?

Sun (London), May 23 1814, p3

On the whole, though, there was outrage, and small wonder. Bread, the staff of life itself, the very foodstuff starving rioters used as their banner, had been corrupted and poisoned. People in the areas worst hit must have viewed their loaves with a caution bordering on paranoia47.

Trahar himself hit back in print, making a public and strident denial of ever having adulterated flour. John Rowe, doubtless assured of a good drink later, backed his boss up, stating that he would “at any time make oath” that he ran Treyew on his own account. Another employee took up the cudgels, making clear his belief that clay had never been used at the mill. Trahar even published another worker’s statement, that of Peter Hancock, making similar denials, but Hancock was not easily bought. In the same newspaper, Hancock issued a rebuttal of what Trahar had put his good name to, and wrote that in July 1813

…I was discharged from Mr Trahar’s service, in consequence of my refusal to adulterate wheaten flour with barley meal.

Royal Cornwall Gazette, June 18 1814, p3

Hardly a smoking gun, but it must have served to further blacken Trahar’s reputation. Bills had apparently been prepared against him, Osler, Trenerry and John Rowe49. The public waited for justice to be done. In fact, they waited two years, until August 1816.

Only Trahar and Rowe stood trial, for

…defrauding the public and endangering the health of His Majesty’s Subjects.

West Briton, August 23 1816, p3

Evidently the screen Osler had built around himself was more bulletproof than Trahar’s. Trenerry & Co.’s complicity was relatively peripheral and thus easy to play down.

The key witness was of course John Holman, who we met earlier. He could put Trahar in Treyew Mill whilst the adulteration process was taking place, as well as describe how the practice was undertaken. Sadly, Holman was a dud. A drunken one. Trahar’s counsel neatly demonstrated how the man stood in court “evidently intoxicated”, and could rubbish his whole testimony. William Trahar was a free man50.

John Rowe had no guardian angel. He must have known he was going down, especially after the testimonies of constables Brown and Clemence. He was fined a further £10, and sentenced to two years in prison51.

He was the only member of the gang convicted.

Yet, Osler and Trahar’s trust credit was utterly, and unsurprisingly, destroyed by the events. Osler was already bankrupt by late 181452.

Trahar sold up and left Truro in 1817. By 1826, we find him bankrupt too, in Southwark53.

It’s difficult, if not impossible, to have any sympathy.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- The Girl Who Played With Fire, Quercus, 2009, p78.

- See: David Cannadine, Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906, Allen Lane, 2017, p59-104; Gavin Daly, “English Smugglers, the Channel, and the Napoleonic Wars, 1800-1814”, Journal of British Studies, 46.1 (2007), p30-46; Walter M. Stern, “The Bread Crisis in Britain, 1795-6”, Economica, 31.122 (1964), p168-187.

- See: William Rubel, “English Horse-bread, 1590-1800”, Gastronomica, 6.3 (2006), p40-51.

- See: Aaron Bobrow-Strain, “White Bread Bio-Politics: Purity, Health, and the Triumph of Industrial Baking”, Cultural Geographics 15.1 (2008), p19-40. Late 1840s Cornwall was not a place for the hungry; see my series of posts on the 1847 food riots here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2022/01/09/the-cornish-food-riots-of-1847-background-and-context/ . Nowadays, the benefits of the brown loaf have finally been taken on board. Sales of white bread have fallen 75% since 1974. From: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2017/jan/04/i-love-sliced-white-bread-its-the-best-thing-since-er-sliced-white-bread

- For more on the National Loaf, see: http://www.teatoastandtravel.com/the-national-loaf/. The West Briton article quoted goes on to summarise the events of 1814 which are the main content of this post.

- Image from: http://www.teatoastandtravel.com/the-national-loaf/

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assize_of_Bread_and_Ale , https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Making_of_Bread_Act_1757 , and J. Kirkland, “Bread Laws and the Price of Bread”, Economic Journal 5.19 (1895), p413-423.

- Image from: https://www.meisterdrucke.uk/fine-art-prints/Thomas-Rowlandson/163700/Dinners-Drest-in-the-Neatest-Manner-%28Satirical-Cartoon-on-Culinary-Hygiene%29.html

- The News (London), June 2 1811, p6.

- Johnson’s Sunday Monitor, October 17 1813, p2.

- Star (London), October 23 1813, p4; Sun (London), January 7 1814, p1.

- Aris’s Birmingham Gazette, April 12 1813, p1.

- Pilot (London), November 2 1813, p4.

- Still from: New Killers of the Victorian Home, Sterling Documentaries, 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9gv5528JZQ

- Dr Annie Gray, New Killers of the Victorian Home, Sterling Documentaries, 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9gv5528JZQ

- Image from: https://www.mediastorehouse.com/heritage-images/great-lozenge-maker-hint-paterfamilias-14829229.html

- Osler was probably born in 1764 (https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=baptisms&id=4750114), Trahar in either 1769 (https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=baptisms&id=4746031), or 1782 (https://www.cornwall-opc-database.org/search-database/more-info/?t=baptisms&id=6545087). For a brief outline on the development of Lemon Street, see: https://bernarddeacon.com/2021/04/24/the-rise-of-the-lemons/. See also: Royal Cornwall Gazette, October 31 1812, p1, and February 13 1813, p2. John Williams, the Scorrier businessman in question, publicly uncovered Trahar’s forgery in the West Briton, February 19 1813, p1. For more on Cornish pennies, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornish_currency#

- Image from: https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/225658937071

- When the crime was uncovered in April-May 1814, it was estimated to have been in operation for around two years. West Briton, April 13 1814, p2.

- Which is surprising: the 1812 harvest had been so successful that potato prices were expected to rapidly fall. Royal Cornwall Gazette, August 15 1812, p3.

- West Briton, May 13 1814, p2; Royal Cornwall Gazette, June 18 1814, p3. It was never proved that Trenerry ever did transport the clay, but they were involved in some respect and a Redruth firm was suspected of doing the work. Plus, Trahar mentions them by name when publicly refuting the allegations made against him.

- Image from: https://www.prints-online.com/new-images-july-2023/tregargus-china-clay-quarry-st-stephen-cornwall-32364032.html

- The price of clay is noted in the Taunton Courier, May 19 1814, p7.

- West Briton, May 6 1814, p2; Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 7 1814, p2.

- West Briton, May 6 1814, p2; Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 7 1814, p2, and June 18 1814, p3. John Rowe would claim in the latter newspaper that he had been in residence at Treyew since February 1814. Generally speaking, he never contradicted Trahar.

- For the image, and more on the china clay industry, see: https://cornishstory.com/2021/01/02/the-china-clay-industry/

- West Briton, May 6 1814, p2, August 23 1816, p3.

- West Briton, August 23 1816, p3. Holman, when giving his testimony, was found to be intoxicated, and thus discredited.

- West Briton, August 23 1816, p3.

- Image from: https://www.hallforcornwall.co.uk/heritage/the-collection/lemon-quay-1905/. For more on Lemon Street and Quay, see Petroc Trelawny, Trelawny’s Cornwall: A Journey Through Western Lands, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2024, p257-9.

- For the record, as recorded in: West Briton, April 24 1812, p4, February 19 1813, p3, September 24 1813, p3, December 24 1813, p3, March 25 1814, p3; Royal Cornwall Gazette, April 17 1813, p3, June 12 1813, p3, July 3 1813, p3, September 10 1813, p3, November 6 1813, p3.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, August 20 1814, p4.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 14 1814, p2.

- West Briton, May 13 1814, p2.

- These probable embellishments are from: West Briton, April 16 1942, p4; Cornish Guardian, October 8 1959, p9. The Portsmouth conviction is noted in Johnson’s Sunday Monitor, November 27 1814, p4.

- Figures from: Taunton Courier, May 19 1814, p7.

- Still from: New Killers of the Victorian Home, Sterling Documentaries, 2018: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j9gv5528JZQ

- The list of subscribers is in the West Briton, February 25 1814, p2.

- See note 31.

- Image from: https://www.mediastorehouse.com/mary-evans-prints-online/new-images-august-2021/bakers-bread-christmas-card-23076524.html

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 7 1814, p2.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 7 1814, p2.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 7 1814, p2; West Briton, August 23 1816, p3.

- West Briton, May 20 1814, p1. See my study of the Cornish cult of effigy burning here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/11/05/effigy-burning-in-1800s-cornwall/

- West Briton, June 17 1814, p2.

- West Briton, May 13 1814, p2.

- For more on food riots in this era, see: E. P. Thompson, Customs in Common, Penguin, 1991, p185-259. See my series here on the Cornish food riots of 1847: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2022/01/09/the-cornish-food-riots-of-1847-background-and-context/

- Image from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_food_riots

- As noted in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, August 20 1814, p2.

- West Briton, August 23 1816, p3.

- West Briton, August 23 1816, p3.

- West Briton, October 7 1814, p3.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 24 1817, p3; Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, October 25 1826, p1.

Fantastic article, congratulations, having been in the industry and later taught the science of bread, I knew about the addition of china clay although more in the upper classes who wanted really white bread as opposed to the working classes who had to eat the healthy wholegrain bread. I find Trahar quite an interesting rogue, especially the fake Scorrier pennies, which I have a small collection of, but the Wiiliams did deserve it to a certain extent, the first evidence of insider trading, and the buying back of the copper coinage as the copper content was worth more than the face value. I look forward to more of your investigations Dave Trevena

http://www.avg.com/email-signature?utm_medium=email&utm_source=link&utm_campaign=sig-email&utm_content=webmail Virus-free.www.avg.com http://www.avg.com/email-signature?utm_medium=email&utm_source=link&utm_campaign=sig-email&utm_content=webmail <#DAB4FAD8-2DD7-40BB-A1B8-4E2AA1F9FDF2>

LikeLike

Thanks for the kind words – stay tuned!

LikeLike