Reading time: 25 minutes

With that serious matter attended to, the County Rugby Championship was revived in season 1919–20. ~ Kenneth Pelmear, Rugby in the Duchy, CRFU, 1960

Lest we forget

Nick Serpell (Hellfire Awaits: 150 Years of Redruth RFC) and myself are currently writing the first book-length history of Cornish rugby, to be published in late 2027. This will build on two previous histories, shatter a few comfortable myths and bring the story of Cornwall’s national sport right up to the present.1 It will also seek to reveal several unheard or forgotten aspects of our winter game.

A previously unexamined facet of Cornish rugby concerns the game during World War One. The long-held assumption is that, as no official rugby was played, then nothing rugby-related can have happened. The years from 1914 to 1918 can be glibly summarised in a neat sentence, like the quote that opened this post. And why not? In August 1914 the CRFU resolved to let the Cornish XVs honour their fixtures as much as possible, but this quickly proved untenable, such was the rush to join up. One by one, the clubs abandoned their matches. So inactive was Cornwall’s rugby calendar that the CRFU didn’t reconvene until January 1919.2

That’s one way of looking at it.

Another way is to appreciate that World War One heralded what one historian has accurately called the age of catastrophe.3 Socially, economically and politically, the nineteenth century, its entire structure of feeling, had not so much been ended as destroyed. The liberal bourgeois democracies of the late 1800s, their empires and capitalist economies, lay shattered. In their place on the world stage came revolutionaries, communists, socialists, Bolsheviks, anarchists, fascists and Nazis. Meanwhile, 20 million people had been either killed or wounded.

Additionally, rugby union’s governing body, the RFU, allied itself to the war effort like no other sport.4 As one historian has stated:

Rugby union saw itself as the very embodiment of the public school imperial ideal: masculine, militaristic and patriotic.

Collins, T. A Social History of English Rugby Union. Routledge, 2009. Page 49

The harrowing results of this campaign and the mindset that allowed it to happen are well documented. Of the England XV that beat Scotland to win the Grand Slam in March 1914, six were killed in action. (Scotland lost six of their team too.) Twenty-seven England internationals died during the war.

But it doesn’t stop there. Rosslyn Park RFC lost 109 of its 350 members who served. Of the 30 who played in the 1912 Varsity Match, 13 were to die. Studies of numerous team photographs taken in late 1913 or early 1914 have led some to conclude that the death rate for rugby players was around a horrifying 30 per cent. That’s four to five players for every XV.5 The RFU thought this was glorious. As the former international (and future RFU president) Bob Oakes put it:

We now know how splendidly the Rugby footballer, in common with every British soldier, fought – aye, and how magnificently he died!

From: Collins, T. A Social History of English Rugby Union. Routledge, 2009. Page 62

If ever you’re walking to Northampton RFC’s stadium at Franklin Gardens from the carpark at Sixfields, you’ll probably find yourself strolling along Edgar Mobbs Way. Mobbs, a wing for Northampton and England, was at first judged too old to enlist and formed his own battalion of fellow sportsmen. He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel and was killed at the battle of Passchendaele in 1917.

Such was the level of warlike dedication the RFU demanded of its players – and the price they paid. His sacrifice is also commemorated on the trophy which shares its name with the Australian international Mark Ella.6

We can conclude then that the relationship between rugby and war is worthy of study. Mine and Nick’s forthcoming book, amongst many other things, considers this relationship as it applies to Cornwall, and will not be discussed here. What this post seeks to do is remember as best we can a group of men whose Cornish rugby club saw more players killed in the war than any other. This post also tries to demonstrate just why this was so. The club in question is the Camborne School of Mines RFC.

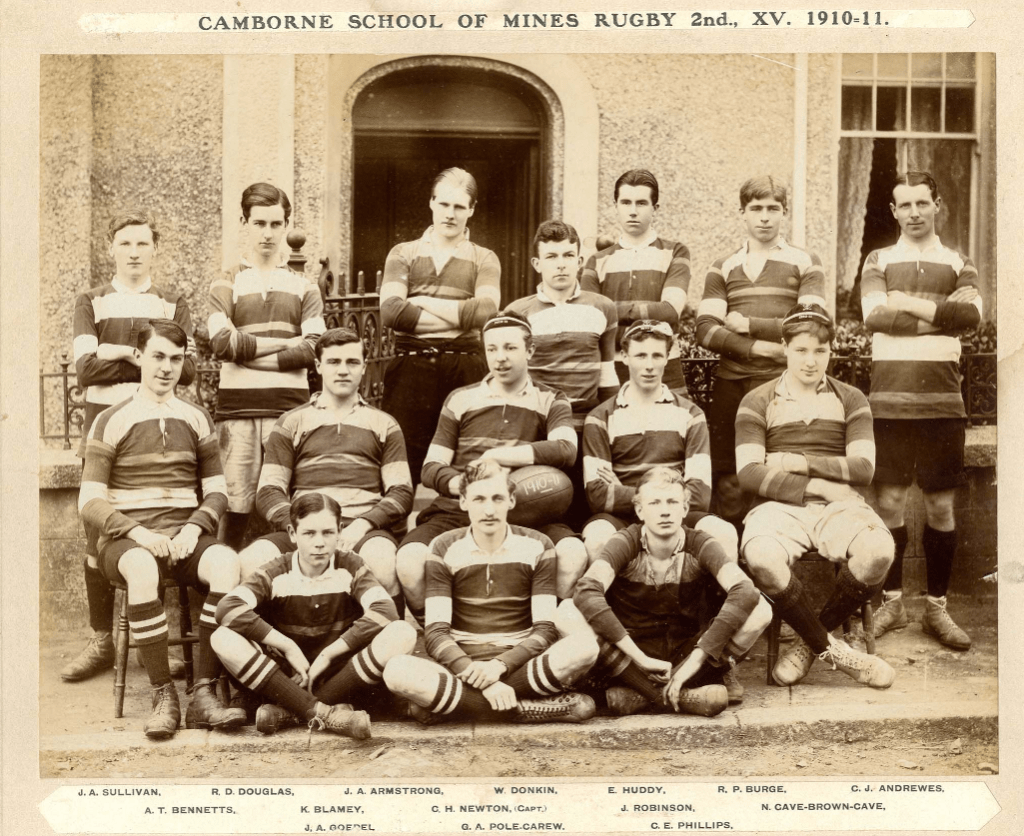

CSM

With its rigorous and lengthy courses, steep fees and qualifications respected worldwide, the Camborne School of Mines was a university in all but name. Advertisements in internationally circulated journals ensured entrants were not just from Britain, but from around the world. In their specialist field, the Camborne school was second only to the Royal School of Mines in South Kensington. Young men, mainly from middle class, public school backgrounds took Camborne and Cornwall to as many distant locations as the Cousin Jacks and Cousin Jennies did.7

The school’s rugby club, formed in 1896, was a force to be reckoned with in this period. By 1914, four of its students were England internationals. Two alumni were in the victorious 1908 Cornwall XV.8

In fact, it was hard to tell which team in Camborne – Camborne RFC, or Camborne School of Mines RFC – held ascendancy. Camborne RFC didn’t even compete in the 1896/97 season, and spent that playing year in abeyance. Journalists began to write of the ‘Camborne Students’ and ‘Camborne Town’ in match reports, thus giving the latter club its nickname. C’mon Town…9

On the declaration of war the students flocked to the colours. By Christmas 1914, 47 of them (and three of their teachers) were in the services, 23 of whom had gained commissions. Only two new students enrolled in September 1915.10 The roll of honour, on display at the school’s new home of Exeter University’s Tremough campus, Penryn, lists 79 pupils who died in the conflict.

The Roll of Honour website also lists the school’s fallen. This has been supplemented by biographical details for each entrant, and here I must congratulate Carol Richards and Martin Edwards on the work they have done. The CSM Association has also produced an impressive booklet on the subject.11

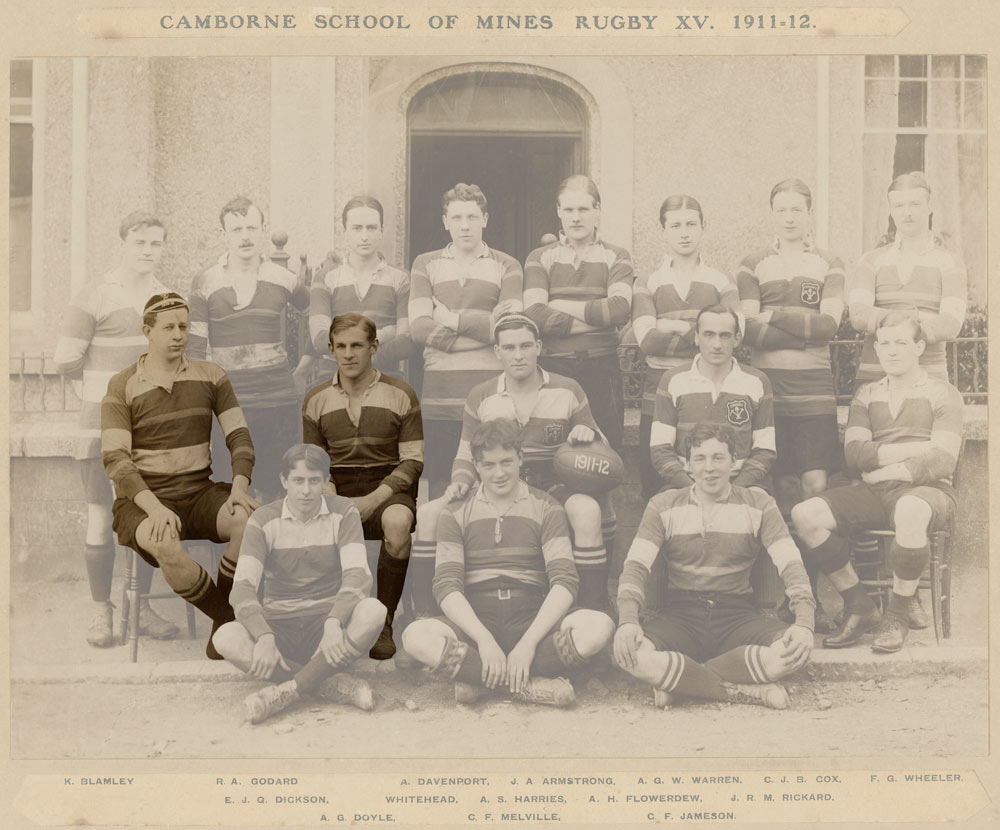

How many played rugby, or were connected to the game? The above webpage gives no clues, but the Association’s memorial booklet has details of some of the school’s most famous sportsmen. Furthermore, it has identified two members of the 1911/12 XV:

In January 1921 the school’s Memorial Committee observed that, of their fallen:

Quite a large number of them stand out as football players. Some of them players with much more than a local reputation.

The Cornishman, 19 Jan 1921. Page two

The names of 11 rugby footballers are listed and, most painfully of all, in some instances their nicknames are also given. But even this number is an underestimate. What follows is, as best I can make it, Camborne School of Mines RFC’s Roll of Honour. I’ve also included those who were involved in the club’s administration.

Charles Percy Lionel Balcombe

‘Bilks’

Born in Tunbridge, Bilks Balcombe attended Camborne School of Mines from 1905 to 1908, and the Memorial Committee in 1921 remembered him as a fine forward for the club. A Cornwall trialist in October 1907, he was unlucky to miss selection and the County Championship glory that came with it in March 1908.12

From 1910 to 1914, Bilks worked for mining companies in Brazil and Mexico, before returning home to enlist with the Royal Engineers. He eventually rose to the rank of Major, was wounded whilst on the first Somme advance in 1916, and was awarded the MC. He was further decorated with a bar in September 1918 for conspicuous gallantry, including rescuing an isolated detachment of men under heavy machine-gun fire.

Charles Balcombe died of his wounds on 29 October, 1918. He was 31.13

John Rowland Barratt

On Saturday, 26 January 1914, Camborne Town hosted the Camborne Students. It was their third fixture of the season. Appearing at scrum-half for the Students was John Barratt, whom the report noted for his ‘good work’, but it was not enough. His XV failed to register a score and Town won comfortably.14

Coming to Camborne from Cheltenham in 1911, John had been an army reservist before joining the Royal Army Service Corps and attaining the rank of lieutenant. He died in France on 24 January, 1919. He was 25.

William Joseph Bellasis

A Londoner, William Bellasis must have been something of a demon sportsman. During his time as a student at Camborne, from 1903 to 1905, he not only played rugby for the school but also enjoyed football and cricket. In 1907 he represented Cornwall’s hockey team.15

William became a private with the East African Mounted Rifles. He died in November 1914 in German East Africa. He was 29.

Morley Berryman

Morley was a Troon boy, the son of a builder. He was a teammate of John Barratt and a member of the XV that lost to Camborne in January 1914. He played on the wing, but isn’t mentioned in the report, which tells us something about the Students’ lack of attacking play that day.

Morley responded to Kitchener’s call and joined a newly-formed battalion of the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry (DCLI). Private Berryman was taken prisoner and died in Turkey in August 1916. He was 21.

Humphrey Layland Braithwaite

One cap for Cornwall, 190616

Born in Cheltenham, Humphrey represented Cornwall as a forward just once, against Gloucestershire in January 1906. John Jackett was in charge, and the XV contained men (for example, Bert Solomon, Nick Tregurtha and Tommy Wedge) that would win the County Championship with him in 1908. But their time was not now. In poor weather at Redruth, the game ended in a pointless draw. Humphrey also played alongside two fellow students, the brothers Henry and John Milton.17

Humphrey attended the Camborne school from 1903 to 1906, and was an outstanding student. He was awarded a place on a postgraduate course, which he took in Mysore, India. He then managed a mine in Newfoundland, and was surveyor of a Brazilian gold mine.

In May 1915 he was a lieutenant with the tunnelling section of the Royal Engineers, and later that year was posted to France. Humphrey was on the Western Front barely five weeks before he was killed in action. He was 31.18

Frederick Crathorne

Not a player, but an administrator: Fred was a student and secretary of the rugby club during the time Humphrey Braithwaite was there. The post was no sinecure. In December 1905 he successfully argued that a referee’s decision to send one of his players off was incorrect and should be overturned. That Fred had to put his case before a CRFU committee chaired by the indomitable Willie Hichens means he had some courage and considerable powers of persuasion.19

Fred had already worked for a year in Swaziland before coming to Camborne; after graduating he held various surveying and assaying positions in Africa, particularly on the Gold Coast. He returned to England in 1915.

As a lieutenant, Fred was attached to the 252nd Tunnelling Company, Royal Engineers. He was killed in action on the Western Front in January 1916. He was 37.20

William Westaway Daw

William, who heralded from Torquay, was mentioned by the school’s Memorial Committee in 1921 as a solid forward for the rugby club. Previous to studying at Camborne from 1900 to 1904 he had been educated in Norway and King’s College London.

After working as an engineer in West Africa and Mexico, in 1908 he returned to Cornwall and managed the Parbola Mine, Gwinear. In 1911 he went back to Africa to oversee mining concerns there.

William became a lieutenant with the Royal Engineers and died of pneumonia in France in November 1918. He was 35.21

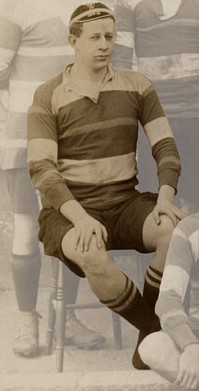

Edward John Quale Dickson

‘Kaffir’

As his un-PC nickname suggests, Dickson, who attended the Camborne school from 1908 to 1911, had been born in South Africa. His talent as a rugby forward lay in his ability to control the ball with his feet, an important aspect of the game in those years. In a match against Camborne in 1910 he dribbled the ball practically the entire length of the pitch, but was denied a try, and had to come off with a dislocated finger. His XV lost.22

He took up mining appointments in Mexico, and during the Revolution there carried out several missions against various bands of armed insurgents.

Commissioned with the Royal Engineers in 1915, Edward achieved the rank of captain and was awarded the Military Cross. He was killed in action in Belgium, in October 1917. His Commanding Officer wrote of him that:

If ever there was a gallant officer he was one, looked up to by all and loved by all.

Royal Cornwall Gazette, 6 Dec 1917. Page five

Edward was 28.23

John Harold Farrar

Though the Memorial Committee mentioned John’s merits as a rugby player in 1921, perhaps he wasn’t a model student. In 1908, the Cape Colony-born John’s last year at the school, he pleaded guilty and was fined for disorderly conduct in Camborne.24

He became a captain with the Northamptonshire regiment and was killed in action in France, in April 1915. He was 27.

Harold Gowans Ferguson

Harold, who studied in Camborne from 1911 to 1913, came from London. A Redruth team inspired by Dick Jackett and Bert Solomon were too much for the students’ side of which Harold was a forward in 1913, but he did earn his 1st XV cap that year. One of his teammates for that Redruth match was Edward Huddy.25

Harold became a major with the Royal Engineers and saw two years’ duty in France, winning the Military Cross. He died in London in November 1918, a result of double pneumonia following influenza. He was 28.26

Harold Greatwood

Harold attended the school from 1905 to 1908, and was born in Tiverton. A back with a massive kick, he made a ‘remarkable’ clearance for the students against Falmouth in 1908, but his team still lost.27

From 1909 to 1912 he was a surveyor for some Brazilian gold mines before returning to England and joining the Royal Geographical Society. He then travelled to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) before taking up his former position in Brazil. A commission in the Royal Field Artillery was offered him in 1916.28

Lt Greatwood died of his wounds in October 1917 in France. He was 30.

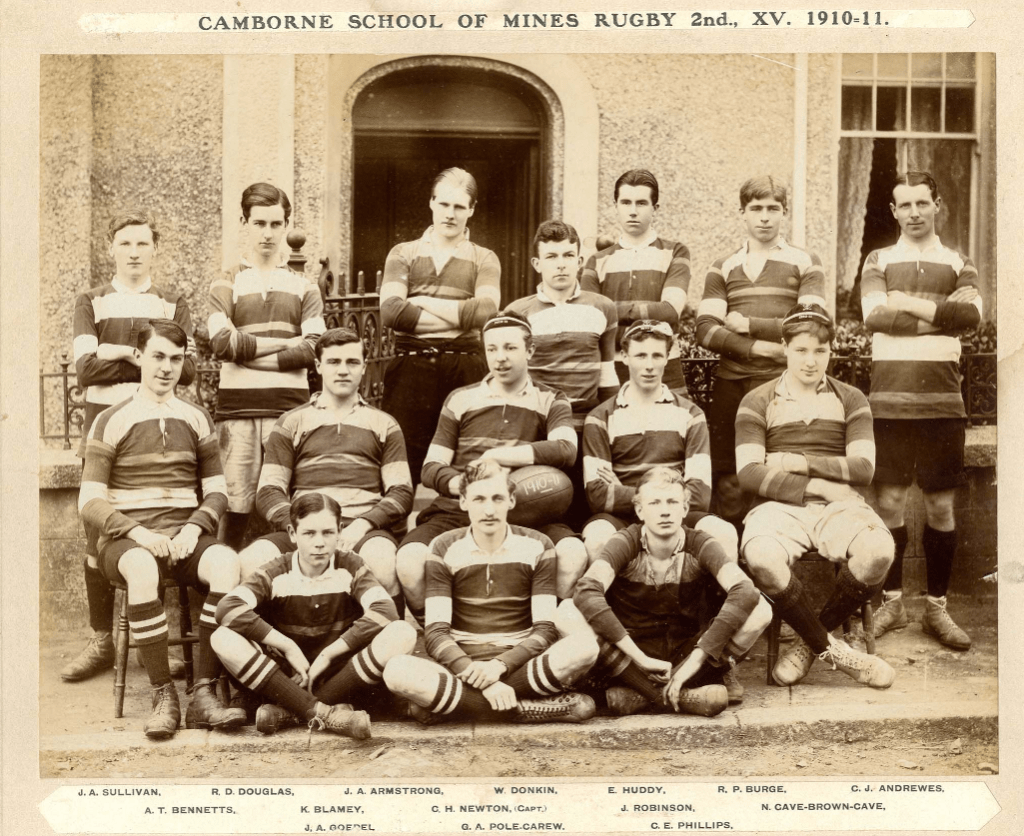

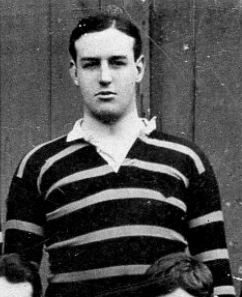

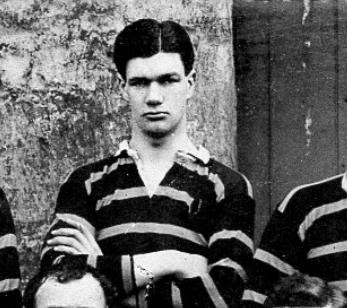

Edward Huddy

As we can see above, Devon-born Edward was a 2nd XV regular, but he did make the odd appearance for the students’ chiefs, alongside Harold Ferguson.

Edward took the rank of lieutenant with the Gloucestershire regiment and was posted to the Western Front. He was killed in action on 30 July 1916 at the Battle of the Somme. He was 24.29

John McMaster Hutchinson

John Hutchinson, a Scotsman who attended the school from 1906 to 1909, played in the same Cornwall trial as Charles Balcombe. Like ‘Bilks’, John’s ambitions on a rugby pitch would get no further.30

John however was a top student. He gained a first class certificate on completing his course, and won prizes in geometry and hydrostatics competitions. An impressive career beckoned. He spent three years at Broken Hill, New South Wales and was home on leave when war broke out.

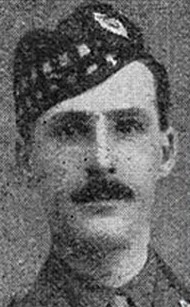

John became a lieutenant with the 9th Gordon Highlanders and was killed in action during the final stages of the Battle of the Somme in October 1916. He was 29.

Alexander Downing Johnson

On Thursday, 23 April 1903, five mining students were up before the beak, charged with causing a disturbance and assaulting police officers. The fracas predictably originated in:

… connection with a football match, where some ill-feeling was engendered.

Reports of the incident outside Cornwall greatly inflated the events, presenting the students as desperadoes armed with revolvers and knives. In truth, it was a minor disagreement between ‘town and gown’, the miscreants apologised, were bound over to keep the peace, and all was forgotten. One of the youngsters in the dock was Alexander Johnson.31

Johnson, from County Kildare, was a player as well as a brawler, being remembered as such by the school’s Memorial Committee in 1921. On graduating he worked for four years in South Africa, and from 1908 to 1912 worked in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), eventually being put in charge of a gold mine.

He resigned his post in November 1914 and joined the South Staffordshires, achieving the rank of captain. He was killed in action at the Battle of Loos in September 1915. He was 34.32

Colin Johnstone MacLaverty

A vicar’s son from Monmouthshire, Colin was as much a career soldier as a mining engineer. He attended the school from 1897 to 1900, but must have left pretty rapidly to serve as a trooper in the South African Constabulary, fighting the Boers. At or around this time he was also prospecting in Alaska. Somehow he found the time (and the energy) to represent the school both as a rugby and football player.33

Colin held surveying and engineering posts in the Transvaal and Nigeria throughout the 1900s; on the declaration of war he joined the North Nigerian Regiment.

Wounded in May 1915, Colin was invalided home, but not for long. That autumn he was appointed captain with the Shropshire Light Infantry. Colin was killed in action on the Western Front in September 1916. A fellow officer wrote:

His company was the leading company, and it was thanks to his fine and gallant leading the whole attack was such a magnificent success. After having captured the first trench he was killed, collecting his men to go and attack the second.

From the Roll of Honour website

Colin was 37.34

William Douglas Madore

A student from 1906 to 1908, William was born in the Orange Free State and was a fine full-back. When St Ives defeated the students 14-3 in early 1909, his strong tackling and clearance kicks ensured his XV weren’t completely embarrassed.35

William sailed for Natal in 1911, but enlisted and was made a captain with the Royal Engineers. He died of his wounds in February 1917, on the Western Front. He was 30.

Ernest Edward Milton

A student from London in the early 1900s, Ernest played rugby, but at first not for the school. The Camborne rock-drill engineering firm, Holmans, formed a team in 1903 and Ernest turned out for them, scoring a try in their victory over Hayle. In August 1903 he crushed two of his fingers in an engine at the firm’s works. No bones were broken, but Ernest’s name disappears from match reports around this time. In 1907, though, he seems to have made a comeback, this time turning out for the school in a defeat by Camborne, alongside William Madore and George Roberts.36

Upon completing his studies, Ernest travelled to Bolivia where he worked as a mining engineer. Like so many others, he returned to England to enlist and became a lieutenant with the Royal Engineers. Ernest was killed in action in France in January 1917. His major wrote that:

The company loses a valuable officer, who was very popular with all ranks.

Marylebone Mercury, 3 Feb 1917. Page two

Ernest was 32.

George Herbert Milton

Ernest’s younger brother, George attended the school from 1907 to 1909. Like Ernest (indeed, like all the Milton boys), he was a keen sportsman, representing the school at rugby but progressing to represent Cornwall as a hockey player too.37

George worked at a Colombian gold mine for three years before taking up a post in Bolivia. From there he went to Nigeria, but returned to England in autumn 1915.

George became a lieutenant with the Royal Field Artillery, and was killed in action in France in October 1917. He was 29.38

The war years were not kind to the Milton family. John G ‘Jumbo’ Milton died aged 30 of pneumonia in South Africa in June 1915. Besides playing rugby for the school, he had represented Cornwall as a forward on 17 occasions, being a member of the 1908 Championship XV. He also won five caps for England.39

Henry Cecil Milton survived the war, but was wounded in France as a captain with the DCLI. He won ten caps for Cornwall whilst a mining student, and a solitary cap for England. He died in 1961.40

Charles Hercules Augustus Francis Newton

With a name like that, why wouldn’t you make him captain of a rugby team? London-born Newton studied in Camborne from 1910 to 1912, and perhaps best personifies here English rugby’s intention to embody imperialism and militarism. His father, Sir Francis Newton, was a senior colonial administrator, mainly in what is now Zimbabwe. In 1924 he was appointed High Commissioner of Southern Rhodesia.41

It was probably natural with such a background that, on declaration of war, Charles would join up. He became a lieutenant with the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. Charles may have carried the name of a mythical hero, but he was all too human. He was killed in action in Belgium, in March 1916. He was 26.

Ian Campbell Penney

Ian came to Camborne from Perth, Scotland, in 1902. The Memorial Committee recalled him as a fine forward; in 1904 he appeared for the students against ‘Town’ alongside Humphrey Braithwaite and Henry Milton. As so often in this period, the match featured no little violence and a Camborne player was forced to leave the field with an injury sustained in a fracas. The game ended in a 13-all draw.42

Upon completing his studies, Ian worked as a surveyor in North Wales, before spending three years at a Tasmanian gold mine. He then travelled to Nigeria, and was home in Scotland when war broke out.

Ian rose to the rank of captain in the Lothian Regiment, and was killed in action at the Battle of Loos in September 1915. His body was never recovered. He was 30.43

George Jewell Roberts

A Perranporth lad, George was a mining student from 1906 to 1909. In 1907, appearing for his school with Ernest Milton and William Madore, he scored a try against Camborne from a five-yard scrum. It was the students’ only touchdown as they went down 18–5.44

George’s qualifications took him all over. He had a year in Spain and two years in Egypt before sailing to Minnesota. He cut his career short on the outbreak of war and returned home to enlist.

A lieutenant with the Royal Engineers, George died of his wounds in June 1916, near Ypres. He was 27.45

William Roland Turner

William only attended the school from 1913 to 1914, but he did get a chance to play rugby. With Morley Berryman and John Barratt, he was a member of the XV that lost a low-scoring match against Camborne in January 1914. A missed tackle by Turner at full-back allowed Town to cross the line, but luckily for him the try was disallowed.46

Originally from London, William became a lieutenant with the Royal Engineers’ 250th Tunnelling Company. He succumbed to wounds in November 1917, on the Western Front. He was 29.

Percy Neil Whitehead

‘Snowball’

Devon-born Snowball had it all. Before arriving in Camborne in 1910 he had been educated at Charterhouse and Cambridge. No slouch on a rugby pitch, he was a Cornwall trialist in 1912.47

He joined the Royal Engineers in 1915 and eventually attained the rank of captain. In August 1916 he was awarded the Military Cross for the following piece of conspicuous gallantry:

When a party of our troops had lost their direction during an attack, he immediately went out and led them to the correct line. At the enemy’s parapet he was wounded in two places at point blank range, but was rescued.

Evening Mail, 26 Aug 1916. Page six

Percy was killed in action on the Western Front in March 1918. He was 29.

Arthur James Wilson

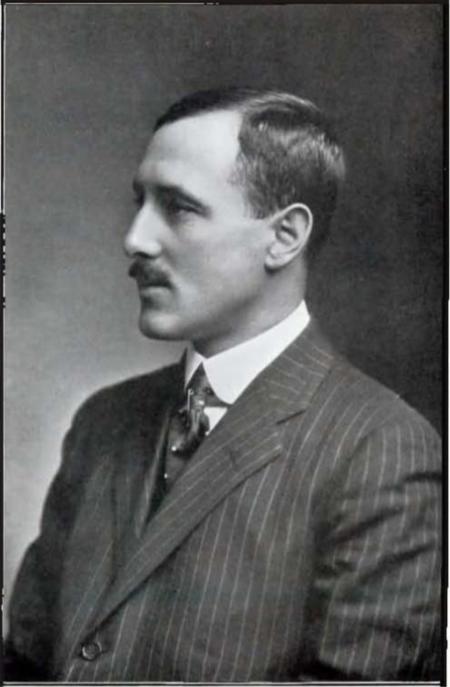

‘Ajax’, 17 caps for Cornwall, 1907–1909

One of Camborne School of Mines greatest forwards was born in Newcastle. Arthur’s rugby career was brief but memorable. He won the County Championship with Cornwall in 1908, and played in their unsuccessful bid for a gold medal against Australia at that year’s London Olympics. A year later he was capped by England, assisting them to victory over Ireland. In the same XV were Edgar Mobbs and Ronald Poulton-Palmer, two of English rugby’s most famous casualties.

He worked in mines along the Gold Coast and in South Africa, and also as a tea planter in India.

Arthur joined the Royal Fusiliers as a private, and was killed at some point during the opening stages of the Battle of Passchendaele in July 1917. His body was never recovered. He was 29.49

The Officer Class

That these 24 men all played rugby for, or were involved with Camborne School of Mines RFC doesn’t in any way explain why they were killed in World War One. Indeed, the fact that they played rugby at all is only important because the RFU insisted it should be so, and I appreciate that this post in no little way perpetuates the RFU’s own myth. No other sport carries its death-toll with such pride.

Indeed, how important was the game of rugby football to these men? All embarked on successful professional careers after completing their courses in Camborne; none seem to have continued playing the game, or taken an active interest in it, when their studies were over. One, Fred Crathorne, doesn’t seem to have played at all. Even the most successful, Arthur Wilson, abandoned rugby to sail to Africa.

Yet they all came back to fight. Patriotism and defence of the Empire, therefore, meant more to these men than facing up to Camborne RFC on a damp Saturday afternoon as a welcome break between lessons. Here we begin to see just why these men joined up, and were killed.

Public schools, said Cardinal Henry Manning (1808–1892):

have made England what it is – able to subdue the earth.

From: Davenport-Hines, R. Enemies Within: Communists, the Cambridge Spies and the Making of Modern Britain. William Collins, 2019. Page 174

Public schools were muscular, Christian, middle class and British. They sought to prepare their pupils for an adult life as members of the ruling cadre, at home and abroad. Nationalism, toughness, conformity, camaraderie and emotional repression were virtues that were instilled with a will. Was not rugby football developed in public schools with these very aims in mind?50

Look at where our rugby players schooled before coming to Camborne. The Milton brothers went to Bedford School, as did William Madore. Snowball Whitehead went to Charterhouse. Charles Balcombe attended Felsted School. Arthur Wilson boarded at Glenalmond College.

They were as much sons of the British Empire as they were of the Industrial Revolution. Almost pre-programmed to answer the call to arms when their country was in danger, their breeding and education also qualified them as leaders of men – the officer class.

It also greatly increased their chances of getting killed. In World War One, ten per cent of all combatant men died; for officers, this figure doubles to 20 per cent.51

Of the 24 members of the Camborne School of Mines RFC who were killed in World War One, 12 were lieutenants, seven were captains, two were majors and three were privates.

One historian writes that:

The toll taken on those recruited was hideous. Young middle-class men – the archetypal rugby players – became junior officers, first in the sights of machine-gunners as they led charges out of the trenches.

Richards, H. A Game for Hooligans: The History of Rugby Union. Mainstream Publishing, 2007. Page 107

Therein lies the tragedy of the men of Camborne School of Mines RFC. We will remember them.

Author’s note

The ‘killed in action’ stamp that appears on the photograph of the 1910/11 XV that heads this post is taken from the service papers of my great-uncle, William George Edwards. He was in killed in action on the Western Front in July 1916.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Pelmear, K. Rugby in the Duchy: An Official History of the Great Game in Cornwall. CRFU, 1960. Salmon, T. The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall. CRFU, 1983.

- The Cornishman, 27 Aug 1914. Page two. West Briton, 23 Jan 1919. Page four.

- Hobsbawm, E. Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century 1914–1991. Abacus, 1995.

- Collins, T. A Social History of English Rugby Union. Routledge, 2009. Cooper, S. After the Final Whistle: The First Rugby World Cup and the First World War. The History Press, 2016.

- Cooper, S. After the Final Whistle: The First Rugby World Cup and the First World War. The History Press, 2016.

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edgar_Mobbs

- Piper, L. The Camborne School of Mines: The History of Mining Education in Cornwall. Trevithick Society, 2013.

- See my post on the 1908 County Championship here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2025/03/28/1908-and-all-that/

- See my post on mining and rugby in Camborne here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/12/26/rugby-and-mining-in-camborne/. The earliest rugby reference I can find to ‘Students’ and ‘Town’ is in The Cornishman, 3 Oct 1895. Page three.

- Piper, L. The Camborne School of Mines: The History of Mining Education in Cornwall. Trevithick Society, 2013.

- See: https://roll-of-honour.com/Cornwall/CamborneSchoolOfMines.html. The player’s biographical details, unless otherwise stated, are taken from here. See also: Richards, C. In Grateful Memory of the Men of Camborne Mining School Who Gave Their Lives for King and Country in the Great War 1914-1918. Camborne School of Mines Association, 2014.

- West Briton, 17 Oct 1907. Page five.

- From: https://nmrs.org.uk/resources/obituaries-of-members/b/charles-percy-lionel-balcombe/

- West Briton, 26 Jan 1914. Page three.

- The Cornishman, 26 May 1904. Page five. Royal Cornwall Gazette, 26 Jan 1905. Page three. West Briton, 28 Feb 1907. Page three. Western Morning News, 21 Mar 1907. Page seven.

- Information from: Salmon, T. The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall. CRFU, 1983.

- The Cornishman, 11 Jan 1906. Page three.

- From: https://nmrs.org.uk/resources/obituaries-of-members/b/humphrey-layland-braithwaite/

- The Cornishman, 2 Nov 1905. Page four.

- See: https://nmrs.org.uk/resources/obituaries-of-members/c/frederick-crathorne/

21. See: https://nmrs.org.uk/resources/obituaries-of-members/d/william-westaway-daw/

22. West Briton, 3 Mar 1910. Page three.

24. West Briton, 5 Nov 1908. Page seven.

25. Royal Cornwall Gazette, 3 Apr 1913. Page three. West Briton, 27 Jan 1913. Page three.

26. London Daily Chronicle, 3 Dec 1918. Page seven.

27. West Briton, 24 Feb 1908. Page three.

28. See: https://nmrs.org.uk/resources/obituaries-of-members/g/harold-greatwood/

29. See: https://stjamestaunton.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/WW1-Memorial-Huddy-E.pdf

30. The Cornishman, 31 Oct 1907. Page six.

31. Cornubian and Redruth Times, 24 Apr 1903. Page three.

33. Royal Cornwall Gazette, 13 Oct 1898, page three, and 22 Dec 1898, page three.

35. Western Echo, 6 Feb 1909. Page three.

36. The Cornishman, 12 Feb 1903, page six, and 13 Aug 1903, page four. West Briton, 23 Feb 1907. Page three.

37. Cornish Telegraph, 28 Feb 1907. Page five. Cornubian and Redruth Times, 5 Mar 1908. Page ten.

39. West Briton, 21 Jun 1915. Page three. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jumbo_Milton

40. West Briton, 22 May 1916. Page three. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cecil_Milton

41. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_James_Newton

42. The Cornishman, 24 Nov 1904. Page two.

44. West Briton, 23 Feb 1907. Page three.

46. West Briton, 26 Jan 1914. Page three.

47. West Briton, 26 Sep 1912. Page eight.

48. Images from: https://worldrugbymuseum.com/from-the-vaults/players/lest-we-forget-arthur-james-wilson-england-31-07-1917, and https://www.crfu.co.uk/home/gallery/

50. Collins, T. A Social History of English Rugby Union. Routledge, 2009.

51. Cooper, S. After the Final Whistle: The First Rugby World Cup and the First World War. History Press, 2019. Page eight.

Hard reading .

tourguidepenzance.wordpress.com

07919681535

LikeLike

Francis,

Thank you for this wonderful article. I am so pleased that my original research in 2013 has helped you in your forthcoming book.

I have a few items that might be of use;

A photo of Charles Balcombe is at the Imperial War Museum – see link https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205289968 * A photo of Joh Farrar is attached * In 2015, there was a project by Bridging Arts and a talk at Penponds Church about the men on the memorial in the porch. Clive Clinch-Carey did the research. I canât find the original spreadsheet, but I will try to find this, as there may have been some non-CSM [Camborne?] rugby players on his list who attended the church. * It took me 4 years to find Michael Stackpole Coxon. He is listed on the brass memorial plaques, but didnât die until 1925 in poverty in Melbourne. A terribly sad story, but I donât think he played rugby. * As a result of the internet, I found additional CSM men, not on the original list. J.R. Barratt, E.J. Pascoe, J Philpot, P.D. Morgan, T O Kelly, E E Lawford, H C Rickard. I think you have them all, but let me know.

Please let me know if there is any help that I can give you in the research for your book. I congratulate you on this long-overdue story.

Regards,

Carol

LikeLike

Francis,

P.s. attached is an article from the CSMA Journal.

Would you like a print copy of the WW1 booklet?

Regards,

Carol

LikeLike

Dear Carol, thank you for your kind words (and the image of Charles Balcombe which I missed). I must congratulate you on the research for the Roll of Honour you carried out; I can genuinely appreciate the amount of digging you must have done! I’m afraid I can’t see any attachment, would you be able to email me at thecornishhistorian@outlook.com? Thanks again and speak soon

LikeLike