Reading time: 15 minutes

In consequence, however, of the failure of the potato crop, prices had gone up beyond their expectation.

Report of the Annual Meeting of the Wadebridge Farmers’ Club, Royal Cornwall Gazette, 25 December 1846, p1

The history of Cornwall in the 18th and 19th centuries was punctuated by rioting, for various reasons. The Camborne Riots of 1873 were motivated by anti-police sentiment; the later riots of 1882 were motivated by prejudice towards Irish workers2. Most riots, however, were generated by hunger.

From the 1720s, to 1847, there were 21 recorded Cornish food riots. The miners, perhaps unsurprisingly, participated in any, and every, incidence of social unrest. So did the other men, women and children of the working class. Where recorded, the number of people prepared to march for grain can be as impressive as it is intimidating: 5,000 on the streets of Truro in 1796, or 2,000 in Manaccan in 18313.

The moral economy of the Cornish crowd

In times of hunger, rioting was the last resort of the starving poor, an option turned to in desperation, yet the discipline and focus of a famished Cornish crowd is noteworthy. A food riot in Cornwall often featured little violence, and no wanton looting, vandalism, or anarchy – though it can be argued that the mere threat of such practices were enough for a large mob to realise its aims. These were not reckless hordes bullying their way into a town and laying waste to all they beheld, in an orgy of injustice and rage. On the contrary, large groups of malnourished outsiders elected spokespeople to negotiate with town officials to fix corn prices, or to ensure no grain was exported from the area by the corn merchants or corn-factors, as they were known. It was only when these more diplomatic efforts failed, that force was employed. The five stages of a food riot have been identified as follows:

- Invasion of the agricultural districts by miners in search of farmers withholding grain from markets;

- Mob action to force magistrates to fix maximum prices of grain;

- Direct action by rioters to impose lower prices on market sellers;

- Looting of grain warehouses;

- Riots to prevent the export of grain in times of scarcity5.

Throughout the May and June of 1847, looting and riots were seen rather a lot.

The causes of the 1847 Riots

The fundamental conflict of a food riot was between builders of Britain’s Empire and commerce, who believed in operating a free inland trade in grain, and the lower orders who maintained that trade should be regulated in their interests, with corn to be sold at a ‘just’, or traditional price: the forces of modern economics meet the forces of folk traditions.

In Cornwall farmers preferred to sell their corn in bulk to factors, rather than piecemeal in local markets. These middlemen, of course, increased the price of corn and looked to export it from the county in an effort to maximise their profits. This is classic capitalism: buy in the cheapest market, and sell in the dearest; or, take your supply to where the demand is willing to pay top mark. Obviously, the Cornish labouring poor could ill afford what they took to be inflated prices, and took a dim view of merchants of any stripe. As the crowd at Redruth told one factor in no uncertain terms that year, they believed that

…all flour-merchants were rogues of the first order…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, July 9, 1847, p1

In years of poor harvests or dearth such as 1847 (the potato blight that resulted in the famine that decimated Ireland also hit Cornwall that winter), farmers would sell all their crops to factors rather than risk them turning bad. Why not? The prospect of a good harvest would lower prices, and their profits, over the summer. More corn was therefore exported from Cornwall in years of bad harvest, and, paradoxically, more was also imported by landlords and mine owners to keep their workers fed. Importing in this fashion of course cost more than simply buying locally. Conflict was perhaps inevitable, between those who sought to maximise their profits – farmers, factors – and those who saw wagons of grain leaving the county and little or none to buy in the local market7.

Why write about the 1847 Riots?

…food rioting [in the rest of England] was already a thing of the past. In Cornwall the riots of 1847 were the final fling of this traditional form of protest.

John Rule, Cornish Cases, Clio, 2006, p43

The Cornish Food Riots of 1847 have received little detailed academic attention over the years. In choosing to riot for food in 1847, it’s maybe perceived that the people of Cornwall persisted with outmoded beliefs and value systems, whilst the English have moved on8.

There’s more to the Cornish Food Riots of 1847 than the last-gasp attempt of the labouring classes to regulate the new market forces in their own interests. At the time, the people who rioted, the farmers, factors and dealers who they rioted against, the figures in authority who sought to pacify and/or patronise and punish the rioters, the soldiers sent in by the authorities to pacify and/or shoot the rioters, and the citizens caught somewhere in the middle, didn’t know that these were to be among the final uprisings motivated solely by dearth and the corresponding high prices of food in the county9.

The Cornish Food Riots of 1847 are worthy of study because, at the time, they had a geographical heft significant enough to be a real cause of concern to the authorities. There were outbreaks in Wadebridge, Callington, Delabole, Camelford, St Austell and Breage. These were not isolated or localised incidents of a few dozen village roughs, putting the frighteners on the farmers and officials, to secure grain at an advantageous price before melting away to their cottages. 300 miners took to the streets of Helston. 3,000 demanded corn in Penzance. 2,000 in Pool. 5,000 faced off against the militia in Redruth. This was a concerted fight for survival, virtually county-wide.

Study of the Riots also give us an insight into the attitudes and culture of the people who lived then, through the reports on the events and individuals involved. There’s emboldened miners, self-righteous women, high-handed magistrates, dutiful constables and victimised merchants. There’s patronising lectures and short, impassioned speeches. There’s cowardice, and bravery. There’s handbills, and tip-offs. There’s negotiation, and violence. There’s fugitives from the law, and harsh punishments. In short, there’s a lot worthy of historical interest.

I’ve broken my work on the Cornish Food Riots of 1847 into four more separate posts:

- Part two takes in the tumults of Wadebridge, Callington, Delabole, Camelford, and St Austell. As they’re all linked, particular attention is given to the uprisings in Breage, Helston and Penzance.

- Part three discusses the rioting in Pool.

- Part four analyses the uproar in Redruth.

- Part five looks at the disturbances in St Austell, and summarises the events as a whole.

Click here to read part two: Rise of the Miners

With special thanks to Deana Schultz Wade, who recommended I start using footnotes.

References

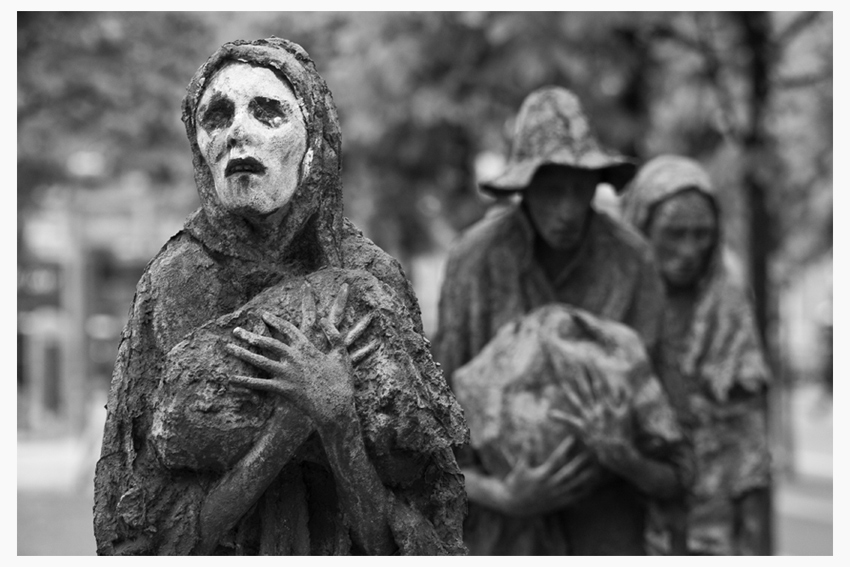

- https://www.visitdublin.com/see-do/details/famine-memorial

- See https://www.camborneriot1873.com, and Louise Miskell, “Irish Immigrants in Cornwall: the Camborne Experience, 1861-1882”, in Roger Swift and Sheridan Gilley (eds.), The Irish in Victorian Britain: the Local Dimension, Four Courts Press, 1999, p31-51.

- See John Rule, Cornish Cases, Clio, 2006, p35-74.

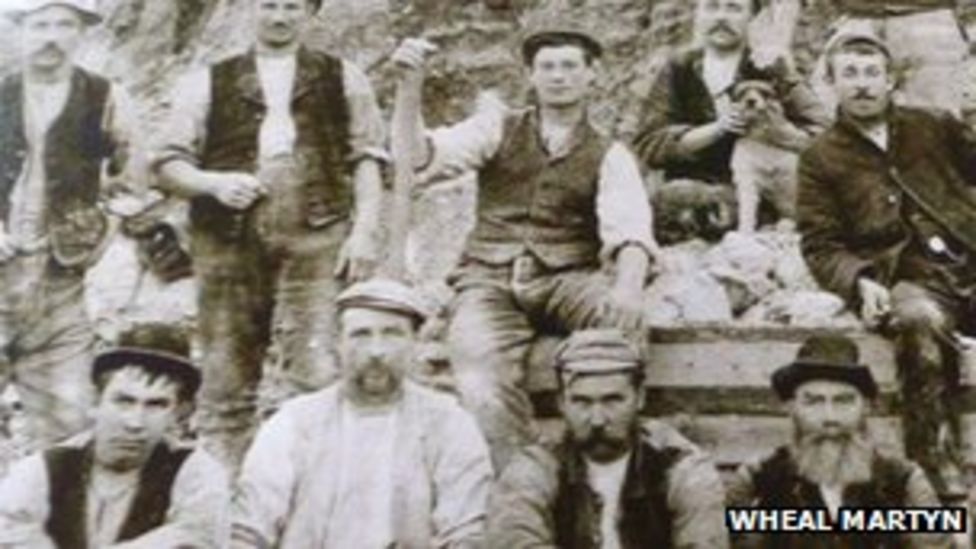

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-cornwall-22294189

- See Rule, Cornish Cases, p35-74. His work draws heavily on what E.P. Thompson called “the moral economy of the English crowd”, in Customs in Common, Penguin, 1991, p259-351.

- https://fineartamerica.com/featured/london-protest-1840s-granger.html?product=greeting-card

- See Rule, p35-74. For more on the growth of free trade capitalism, see Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Capital 1848-1875, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1962, p36-9. A good general text on Ireland’s suffering at this time is The Great Irish Potato Famine, by James S. Donnelly, Sutton, 2001.

- John Rule’s fascinating essay on Cornish food rioting in Cornish Cases sadly omits the events of 1847. Ashley Rowe produced an article for The Report of the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society, vol. 10, in 1942 (p56-67), and this is a worthy narrative. However it lacks any socio-historical analysis, which Rowe himself admits. This will be discussed in a later post. Kresen Kernow hold a research project by Kevin Thomas from 1996, Food Rioting in Cornwall (1727-1847): With Some Comparison to Contemporary Wales, but is relatively short, and employs the same timescale as Rule. Philip Payton discusses the Riots in The Cornish Overseas to develop his theme of the Cornish emigrating on account of the food shortages of the time (Cornwall Editions, 2005, p129-35). There is also an article online by the Penwith History Group, which is really more of a brief survey.

- Incidentally, the year 1847 didn’t mark the end of food rioting in England. The London Express of January 13, 1854 reports the trial of food rioters in Exeter (p2), and Reynolds’s Newspaper of November 17, 1867 reports a “desperate” food riot in Oxford (p4). For more information on the Exeter riot, it’s discussed on the Devon Radical History Facebook page, and an article is available here. Thanks to Dave Parks for sharing this.

No food banks then.

LikeLike

What a fantastic article, my only question is, why on earth don’t we get taught this at school, it’s such an important

piece of history. My grandfather was a miner at East pool mine as were most of my relatives. Please keep up the good work.

LikeLike

Brian- we must share a few genes. My Temby line started in pool but migrated to the USA about 1860.

LikeLike

My IVEY line was in Pool there in 1841 census and in Illinois Usa in 1850.

LikeLike

Excellent article and I look forward to reading the subsequent ones.

I also can echo an earlier comment – why are we not taught this important part of local history? It’s far more interesting and relevant.

LikeLike

Great job Mr. Edwards. I hadn’t any idea all this went on. Your articles are so educating. P.S. Thanks for the shout out.

LikeLike

Enjoyable read. Only one thing, Cornwall was not a county then. The legality of it as a county now is dubious according to the Kilbrandon Report or Royal Commission into the constitution.

LikeLike

Thank you very informative.

LikeLike

Why are we as cornish people not taught this at school? we are taught very little of our Cornish heritage, disgraceful

LikeLike

Worth mentioning that the same blight that affected Irish potatoes also struck Cornish potatoes – meaning a subsistence crop that would normally be available was lacking in 1846 and contributing to famine locally. So it seems a bit like ‘Trevelyan’s corn’ grain merchants in Cornwall were also profiteering whilst the working class starved.

LikeLike

I think the failure of the potato crop in Cornwall in those years must also have been a contributing factor to the Cornish diaspora as was the discovery of copper in South Australia where many Cornish emigrated.

LikeLike

And also the Scots at the exact same time, the weather had been biblical all over the British isles & had little time to dry out between seasons and the many diseases created by the then lethal asiatic flu that had conquered all in many areas at the exact same time .

This Asian Flu came up from the South West & was only 2nd in devastation levels to the Spanish Flu brought back by our troops from WW1 , a Flu that affected the majority of all the nations that fought in that horrible 1914 – 1918 conflict, the Spanish Flu itself had killed millions of people overall .

CC

LikeLike