Reading time: 25 minutes

(If you missed Part One, click here…)

As we saw in Part One, Camborne’s Police Force in the early 1870s was believed by many townspeople to be taking their duties to oppressive extremes. Over the first weekend of October 1873, two brothers, James and Joseph Bawden, were arrested for assaulting several officers. When in prison awaiting trial, they were alleged to have been beaten up by the constables.

Several thousand angry and armed people crowded around Camborne Town Hall on Tuesday, October 7 to hear the outcome of their hearing. It was hoped that the counter-accusation of police brutality would get the brothers off. Failing that, rescue was contemplated…

4pm…

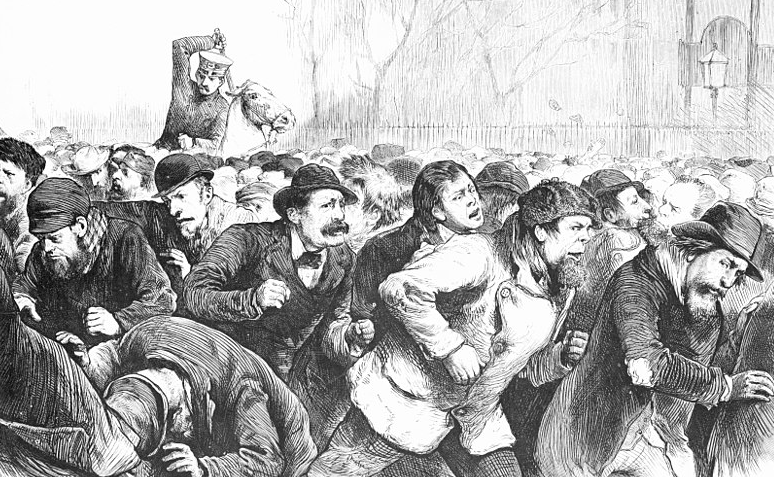

Suddenly the doors of the Town Hall fly open, and out rush a half dozen PCs. No doubt screaming like banshees and waving their staves, they fall on the crowd. Taken by surprise, the mob falls back but rapidly regroups to recommence hurling stones at their assailants2.

But this is only a feint. Col. Walter Gilbert, Cornwall’s wily Chief Constable, had the officers sent out front whilst, quietly and around the rear of the Town Hall, the now-sentenced Bawden brothers, with Gilbert himself, are slipped away in a carriage. They escaped via Treswithian Turnpike and on to Bodmin Gaol3.

James and Joseph Bawden were to endure five harsh months on the treadmill at Bodmin for their assault on PCs Harris and Osborne5.

Whilst the subterfuge was taking place, the police were busy taking retribution out on the crowd that had been pelting them with rocks for several hours. One was PC 28, Sgt Currah, who, upon coming across a “tall youth in dark clothes and a billycock hat” engaged in the act of hurling a rock,

…cut him down with my staff, right enough…

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

The distraction had done its job. The Bawdens were gone. The officers retreated indoors, doubtless pleased to have meted out some rough justice.

Dreadful…

James and Joseph may have been halfway to Bodmin, but the crowd wasn’t going anywhere. When the discovery was made that the brothers had exited, quite literally stage-left, a cry of anguish from the outraged mass went up that was

…positively dreadful…

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

What followed can only be described as carnage. Rocks fell on the Town Hall with renewed vigour. Miners, bal-maidens and their brats joined in. Windows were shattered. Glass spilled onto the streets as well as covering those cowering inside. The noise was terrific. The heat was on. It was too hot for some.

Richard Holloway, prosecuting, must have realised that the man who’d sent the Bawdens to prison and come from Redruth to do so was in serious danger. He took no chances and escaped by running through a garden and climbing a wall6.

Supt. Stephens was the detested commander of the Camborne force. Like some kind of Oriental despot he was said to have had female prisoners stripped naked in his presence7. But with his back to the wall, he abandoned his post, and his men, in a carriage. For this, he was denounced in the Press as being as

…great a coward as he was a tyrant…

West Briton, October 16 1873, p4

He was never seen in Camborne again. Citizens rejoiced, and the men under his command must have been glad to see him go as well. Because right now, they were in trouble.

Toughing it out in the Town Hall was quickly abandoned as unfeasible for the 30 or-so besieged and injured police force. All around them lay broken glass. All they could hear was people outside baying for their blood. Stephens had deserted them. Gilbert had gone with the Bawdens. What the hell are we going to do?

The beleaguered officers had no choice but to make a run for it to the relative safety of Moor Street station. And this meant charging through an armed mob thousands strong under a hail of rocks.

To get themselves out of trouble, they first had to get into more trouble.

Gathering themselves and their weapons, they hurtled out of the Town Hall and met the townspeople head on. Staves striking flesh. Stones finding their mark. Screams of pain and anguish. Grunts of masculine effort. Fists pounding faces. Claret spilled. This maelstrom of a brawl continued up Market Place and into Trelowarren Street. Nowadays we would identify it as having happened between The White Hart, JJ Kebab, and USA Chicken8.

You’ve got company…

Here and there, through the haze of battle, individuals can be discerned. Inspector George Pappin, pressganged into coming to Camborne that day (and probably regretting it), was struck on the head by a rock. His alleged assailant, a man called James Kent (and more on him later), felt the full force of law and order when Pappin cracked him one in retaliation over the face with his stick9.

PC 124 George Bowden may well have been the officer who was noted to have “hewed his way through the maze” with his bludgeon. He was the last to leave the Town Hall, at 5pm. He later said, with brilliant understatement, that there was

…plenty of company…

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

On the whole, however, the Police were outnumbered and outgunned.

They didn’t know whether to make for Moor Street or quit the town completely. Several of them obviously weren’t sure how to get back to the station. They couldn’t know if anyone they came across was going to attack them, offer them shelter, or, if their erstwhile protector might have a change of heart and turn them over to the rioters. Every bend in the road, every new street, might result in fresh dangers.

PC 17 Richard Oliver’s normal beat was Devoran. He was found hiding in a van by the mob and set upon. On later examination, he was found to be concussed, with a heavily bruised back, legs and shoulders. One leg was lame, and an eyeball was seriously inflamed10.

PC 58, Aaron Dingle, was from Hayle. He hid in a kindly citizen’s house, who guarded Dingle by standing in his doorway, brandishing an axe11.

An anonymous policeman was found hiding under a bed in an upstairs room of a restaurant by members of the mob. He was dragged out, screaming, one imagines, and beaten up in the street.

Eight PCs ran down Gas Street, pursued by a large number of attackers. So desperate were they to make their escape, the officers nobly abandoned two of the slowest among them to their fate; one of whom, allegedly, fought off two hundred rioters with his stave. They dashed pell mell through a cobbler’s shop – one can picture them upending stock in their panic, the stooped, bespectacled cobbler narrowing his eyes at the intrusion – and got to Moor Street12.

As a Camborne officer, PC 4 Martin Burton was a marked man. Of him, the mob demanded

…severe treatment…

West Briton, October 9 1873, p4

Thomas Hutchinson, a surgeon, advised him to scarper to Redruth on the Redruth-Helston conveyance. Hutchinson even went so far as to advise the driver to take an alternative, quieter route.

Well, that’s the story Hutchinson gave the authorities at any rate. Somehow, Burton’s escape vehicle was located and its windows smashed. Burton was hauled into the road and kicked senseless13.

And so it went on, all afternoon and evening. The people of Camborne were sick of their policemen. They wanted them kicked out of town. And in this, they were victorious. They’d taken back the streets.

In recognition of their triumph, an officer’s helmet was jammed onto a pole and paraded about the streets, in a time-honoured mob ritual14.

It was grudgingly conceded that

…the whole town, was from about five o’clock in the afternoon until about four o’clock the following morning at the mercy of the mob.

West Briton, October 9 1873, p4

Moor Street

For those officers that did make it back to Moor Street, the station offered them as much shelter as the Town Hall previously. But many had no choice – their wives were inside.

They must have known that, sooner or later, the miners would come knocking. Like a Norman keep oppressing the Saxon peasants in its shadow, the capture and ownership of this building must have represented to the rioters the final transfer of authority and justice in Camborne from the Police to themselves.

From 6pm onwards, the station was ransacked. Supt. Stephens’ trap was dragged outside, then smashed and hacked to pieces. Windows were shattered. Stable doors turned to kindling.

The officers and their spouses, described as terrified and snivelling, were allowed to leave unmolested, apart from one. He was fool enough to hand over his jacket, with assurances of a safe passage. Thus emasculated, he was soundly thrashed before his distraught colleagues.

The truce, if truce there was, didn’t last long. One of these policemen was later discovered in Trelowarren Street, beaten unconscious amidst the debris that had been made of the Superintendent’s conveyance.

The station was completely vandalised, with furniture, utensils and decorations being destroyed. Prisoners were released. Fires lit. Ruination reigned – think of the animals entering Jones’s house in Animal Farm. A handful of the Bawdens’ belongings was discovered and spirited away to their families.

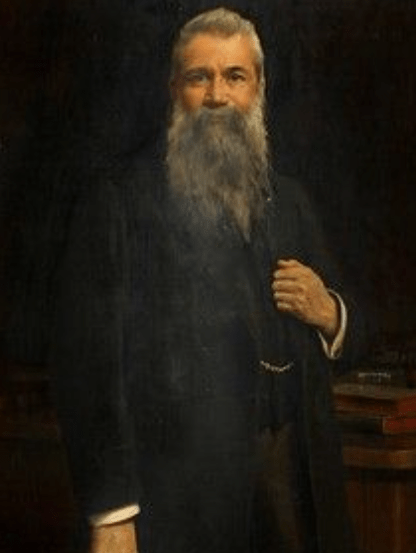

As if from nowhere, fuse magnate William Bickford-Smith appeared at the entrance to the station on horseback, in an attempt to justify the sentencing of the Bawdens to the mob. It may have fallen on deaf ears, but you have to admire the man’s courage15.

For he was on his own. He couldn’t read the Riot Act, as there was nobody in town with which to enforce it. The nearest armed force was in Plymouth. And swearing in willing deputies was also a non-option, for he would have been all-too aware that

…prejudice against the police force was by no means confined to working miners…

Royal Cornwall Gazette, October 11 1873, p8

Nowhere in Camborne was safe.

Night shift

The Reynolds Arms, on the corner of Trevenson Street and Stray Park, was attacked in the evening. Either the gang of emboldened rioters, led by a local cobbler called George Pascoe17, had suspicions that landlord William Newming was harbouring an officer, or they had some scores to settle.

The pub doors were forced open, and the bar completely trashed. A barrel of ale was rolled on to Trevenson and smashed up. While his wife and niece hid upstairs, Newming was coshed. Some enterprising young spark then daubed the hostelry’s exterior with the following warning:

A Camborne mob, its mark.

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

Several hundred shadowy characters were now abroad, using the circumstances of the riot as an excuse for general anarchy. They menaced Bickford-Smith’s mansion on Beacon Hill, harangued the residence of a lieutenant of the volunteers, and supposedly tore the railings off a magistrate’s house18.

All was done with complete impunity. Camborne’s police force and its reinforcements were lying low and sleeping rough. It can’t have been a comfortable night.

At or around this time, the combined forces of St Ives and Redruth’s miners made contact with their compatriots in Camborne. The plan was simple, yet outrageous: to blow up Redruth County Court, a building long unpopular with working men for

…frequent summonses…for small debts…

West Briton, October 16 1873, p4

No rebellious horde from St Ives or the other side of Carn Brea materialised. Redruth County Court wasn’t blown to smithereens, like a bank in a spaghetti western. No longer a court, the building still stands, on Penryn Street.

Another figure of authority had returned to Camborne by the evening. This was Colonel Gilbert, Cornwall’s Chief Constable, fresh from delivering the Bawdens to Bodmin Gaol20. Where he stayed however is not known.

Surely, though, he and Bickford-Smith must have conversed. And if they did, they must have concluded that enough was enough.

Dawn, Wednesday 8th October…

The early hours. Whoever took the decision is unclear, but we can posit Bickford-Smith or Col. Gilbert. Time to pull things back. Time to send a hasty telegraph message.

Camborne was now about to experience martial law.

At around 4am, a hundred soldiers of the 11th Regiment alighted at Camborne Railway Station and set about patrolling the town. Some Red Jackets were billeted at the Reynolds Arms. Indeed, until their departure on the Saturday, this military presence was highly visible.

Curtains twitched. Doors locked. Miners hurried to their shifts. Glances were exchanged. Were they ordered to shoot on sight? No one knew.

Pubs were ordered shut. Plainclothes policemen sauntered about, eyeing up any likely lad, hoping for a name. Shards of glass were on the streets outside the Town Hall. The Reynolds Arms was covered in graffiti and vandalised. Moor Street station was a sorry wreck. Detritus of the events of yesterday spread over the streets21.

It wasn’t until Thursday 9th that around 50 Special Constables were sworn in, with instructions to

…proceed instantly, in case of any outbreak, to the police-station in Moor-street…

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

Clearly the local magistrates had little hope of maintaining order after the departure of the Redcoats, though the men they deputised can’t have instilled them with much confidence either. For example, one unenthusiastic Special gave the following statement to the magistrates, the object being to

…justify my dislike to taking this oath, and to state that I do it under protest – in fact I would not do it at all were I not compelled to…

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

But the authorities had two important jobs to perform. The first was a straightforward find-the-rioters. Second, and more delicately, they would have to be, to some extent, investigating themselves. The allegedly heavy-handed, tyrannical conduct of Camborne’s policemen couldn’t be brushed under the carpet.

A petition signed by prominent tradespeople and presented to Col. Gilbert highlighted the ill-feeling Camborne’s force had cultivated amongst the citizens of the town – not just the miners and the working classes.

It emphasised the harsh nature of the officers’ conduct and the (not-unfounded) accusations of brutality toward arrested suspects. The charges, stated the petition,

…can be partially, if not wholly, substantiated…

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

This petition was the silk glove of respectability around the mob’s fist.

The magistrates must have looked at each other. The lower orders griping about the forces of law and order was nothing new, but respected tradespeople? The great majority of Camborne’s population had lost faith in the police.

Time to restore trust. Col. Gilbert gathered himself. He stated that he would

…in a spirit of fairness…investigate any charge, and also the general charges, brought against the police…

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

Trial and dismissal

Gilbert was as good as his word. By October 18,

…with reference to the late Camborne riots, the Chief Constable of Cornwall has decided upon careful inquiry that the police exceeded their duty. All the men will be removed.

London Graphic, October 18 1873, p363

Supt. Stephens was dismissed on October 12. PC 51 John Harris was moved to the Helston borough. PC 4 Martin Burton was forced to resign on October 21. PC 136 Francis Bartlett was transferred to Truro on October 13. PC 61 James Osborne was transferred, then forced to resign in December. PC 21 Charles Nicholls was transferred to Truro in November 187323.

The trial of the alleged rioters, which took place a week later in a Town Hall still devoid of windows, was a complete farce.

George Pascoe, the man who led the attack on the Reynolds Arms, was never caught. He skipped town before being arrested, though he was later back living in Union Street24.

Three men eventually stood in the dock: James Kent, of Tuckingmill Foundry; Inspector Pappin had lashed him one across the chacks at the height of the riot; Cornelius Burns, a miner from Dolcoath alleged to have been throwing stones; and James Bryant, another Dolcoath man who may have been present during the sacking of the Reynolds Arms.

They were all acquitted for lack of evidence. Indeed, the witness statements barely establish evidence of a riot at all in Camborne, let alone anything else. Here’s a sample, all made by respectable citizens:

…I cannot recognise any rioter…Boys mostly threw the stones…[I] could not give the Bench the name of any one who rioted…I did not know any of the rioters…

Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3

Either the witnesses had been ‘got at’ by the miners, or they were suffering the biggest case of collective amnesia in human history, or they knew very well who the perpetrators were – but decided to keep quiet.

No one was ever convicted of participating in the Camborne Riots of 1873.

It remains the biggest anti-police riot in Cornish history.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

References

- From: One & All: A History of Policing in Cornwall: The Cornwall Constabulary 1857-1967, by Ken Searle, Halsgrove, 2005, p18.

- West Briton, October 9 1873, p4.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, October 11 1873, p8.

- From: One & All: A History of Policing in Cornwall: The Cornwall Constabulary 1857-1967, by Ken Searle, Halsgrove, 2005, p18.

- From: Cornwall, England, Bodmin Gaol Records, 1821-1899, Reg. #12, Vol. no. AD1676/4/11, Ancestry. For more on Bodmin Gaol’s treadmill, see: https://www.bodminjail.org/discover/about-bodmin-jail/punishments/

- Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3. For more on the interesting career of Richard Holloway, see my post here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2022/09/06/murder-debt-riot-richard-holloway-redruth-solicitor/

- See Part One of the Camborne Riots here.

- West Briton, October 9 1873, p4.

- Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3.

- Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3.

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, October 11 1873, p8.

- Cornish Telegraph, October 8 1873, p2.

- West Briton, October 9 1873, p4; Lake’s Falmouth Packet, October 11 1873, p1.

- Cornish Telegraph, October 8 1873, p2. Few riots or popular disturbances in 18th and 19th century England were seemingly without this trope: that of the object of the mob’s anger being symbolically paraded before them, be it a loaf of bread or ear of corn in a food riot or, as here, a policeman’s helmet. See E. P. Thompson, Customs in Common, Penguin, 1991, p257.

- From: West Briton, October 9 1873, p4; Lake’s Falmouth Packet, October 11 1873, p4; Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3.

- As mentioned in the West Briton, July 31 1950, p2. The pub was reported as being discovered to be open after licensable hours. Not for the last time.

- 1871 census.

- From: Lake’s Falmouth Packet, October 11 1873, p1; Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3.

- See: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1142565

- West Briton, October 9 1873, p4.

- From: West Briton, October 9 1873, p4; Lake’s Falmouth Packet, October 11 1873, p1; Royal Cornwall Gazette, October 11 1873, p8; Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3.

- West Briton, October 16 1873, p4.

- From: One & All: A History of Policing in Cornwall: The Cornwall Constabulary 1857-1967, by Ken Searle, Halsgrove, 2005, p81, 86, 99, 106, 111, 113.

- Cornish Telegraph, October 15 1873, p2-3, 1881 census.

Another good one Francis

<

div>

Nick SerpellSent from my iPad

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike

Thankyou!

LikeLike

Thank you Francis for this continuation of the story of the Camborne Riots 150 years ago – well written and gripping.

LikeLike

Many thanks Elaine

LikeLike

Interesting! My late father, born in 1902, left Cornwall and all sorts of trouble to come to Australia. Landing in Fremantle, W.A., he worked his way across to S.A. , then to Victoria, where he married my mother and lived out his life. He spoke of all sorts of things in Cornwall, but he was, of course, not old enough to have known the riots. Strikes, yes!

These events provide an understanding of the riot in Ballarat at Eureka Stockade! No freeman liked a policeman!

LikeLike

a riveting read , i hope the bawdens were allowed to settle back into the community. i hate to think how they were treated . i would like to know more about anthony cock , he sounds like a fair man. thank you for the information

LikeLike