Reading time: 30 minutes

He was outspoken in his opinions and feared no man.

~ The Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5

Human life was the cheapest thing in Butte.

~ Hell With the Lid Off: Butte, Montana, by Horace Smith, New Bay Books, 2021. Kindle edition, p178

From Gas Street to Montana

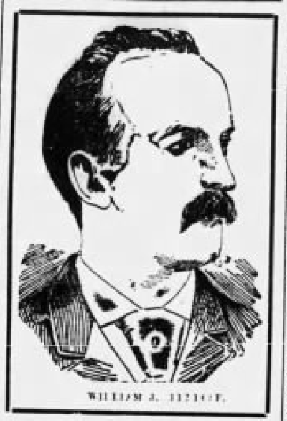

One of Butte, Montana’s more controversial citizens – and there were many in his day – was born in Camborne in 1855. In 1861, young William John Penrose was living with his family in Gas Street1.

His father was a miner and a “religious enthusiast”, and Penrose may have inherited his flair for the dramatic and sense of self-promotion. Hundreds of people once flocked to witness Penrose Senior’s spiritual trance that was alleged to have lasted over a week2.

Although in 1871 the Penroses were still residing in Camborne, by the end of the decade they had emigrated to the United States. The US Census of 1880 finds W. J. Penrose in Braidwood, Illinois, and making a living as a coal miner.

Though we may question claims that he had been an itinerant preacher and a gun-packing lawman, he was certainly well-travelled. Before shaking the dust off his boots in Butte in around 1885, Penrose, acquiring a wife along the way, had also passed through Vermont, Pennsylvania, and Eureka and Virginia City in Nevada3.

During his adventures, he also developed a taste for hard liquor, strong tobacco, working-class activism, sport, politics, the night-life, fast women, and journalism (though not necessarily in that order).

All these, along with a caustic tongue, he brought to Butte.

Hell With the Lid Off

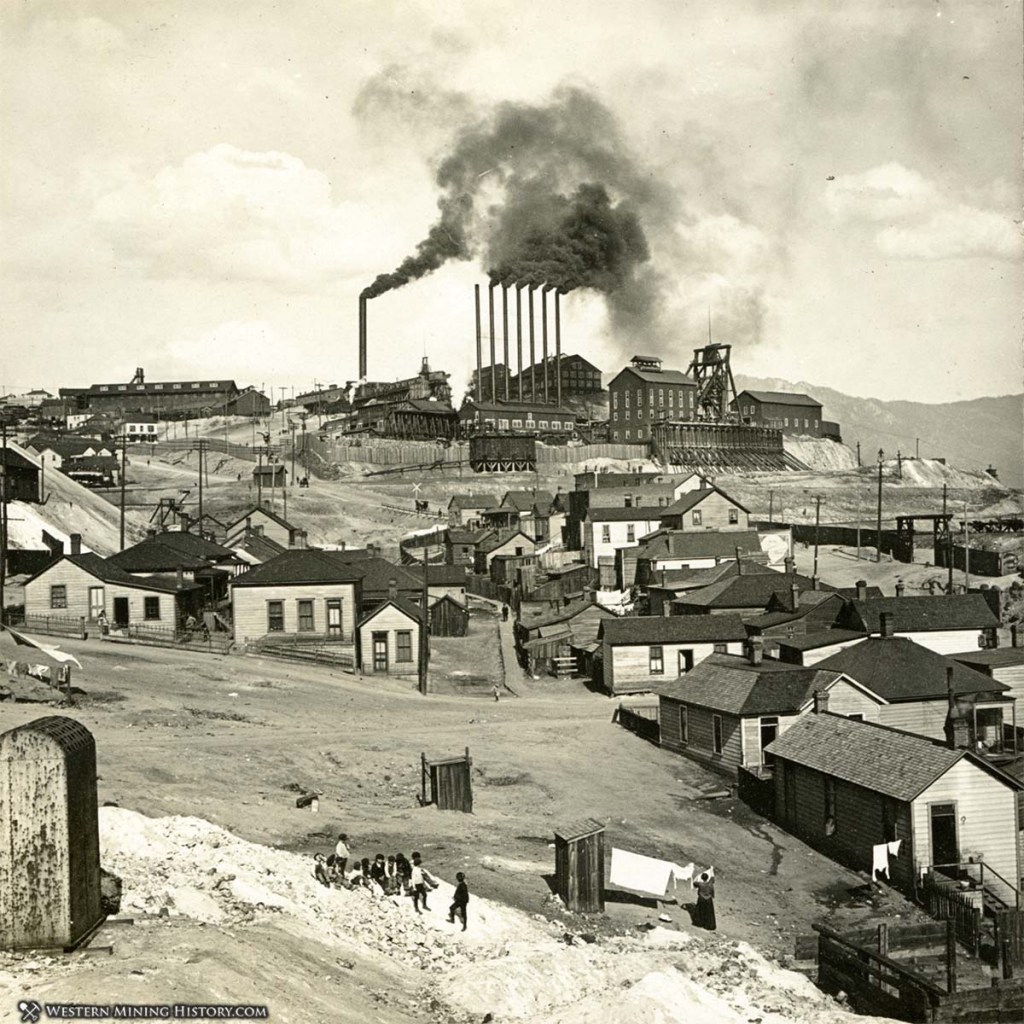

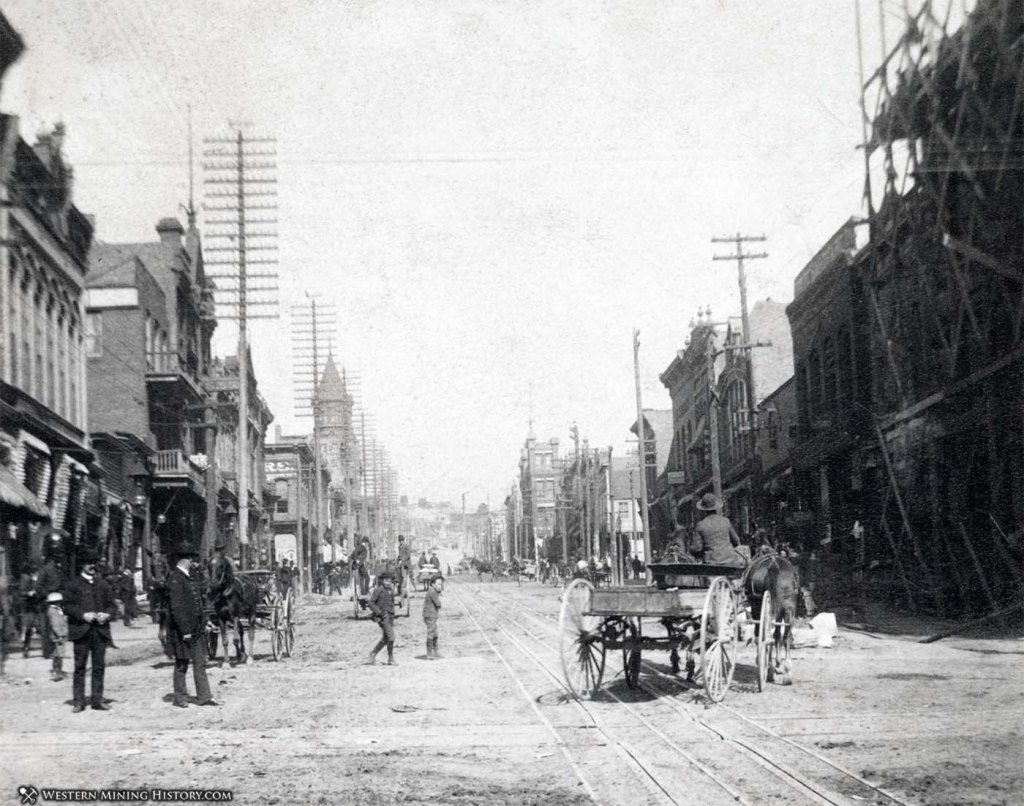

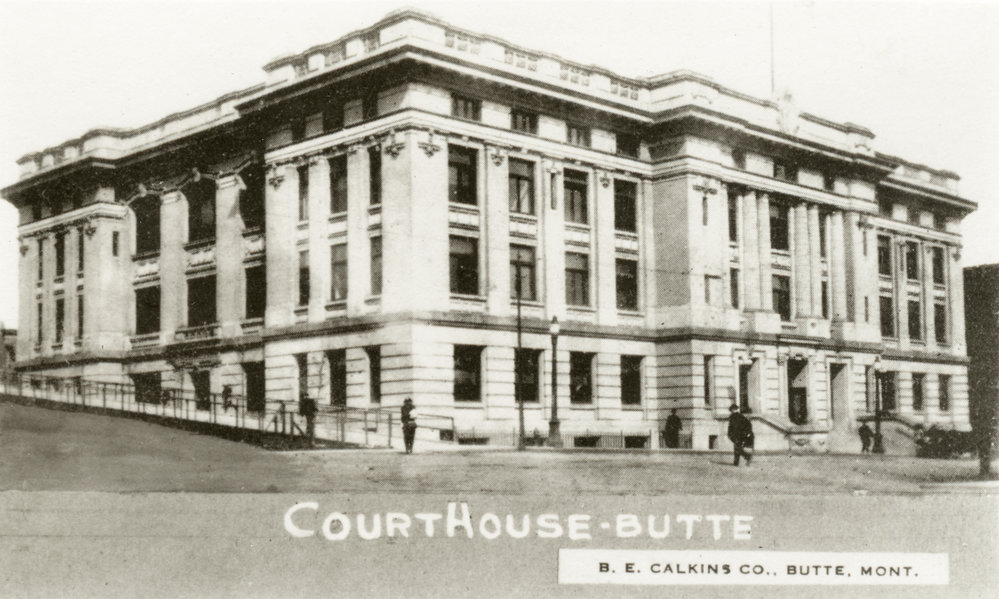

Butte (pronounced bewt, as in bewty), Montana. Even its name sounds tough, though perhaps not as intimidating as the nearby settlement of Anaconda. In 1874, Butte’s residents were a measly 61 scrabbling prospectors. By 1917, it had a population of a 100,000, and was a bona fide Wild West boomtown5.

With the accelerated industrialisation, population growth and attendant disparities of wealth, Butte bore many characteristics of your classic frontier settlement. We are blessed that a personal memoir exists, describing Butte in the 1890s. It’s called

Hell With the Lid Off

Never has a book had a better title, or there been a town with a more fitting description6. Not only was Butte

…the wickedest town in the United States, but with the added offense of boasting of that fact…

Horace Smith, Hell With the Lid Off: Butte, Montana, New Bay Books, 2021. Kindle edition, p78

Butte had it all: saloons, spittoons, joyhouses, opium dens, card-sharps, horse-thieves and pickpockets. There was corruption, brawls, vigilantes, lynchings and, of course, gunfights. So regular an occurrence were shootouts that

There was never anything approaching a panic at ordinary little encounters of this kind…

Horace Smith, Hell With the Lid Off: Butte, Montana, New Bay Books, 2021. Kindle edition, p35

Murder, therefore, was rather commonplace. Human life was reckoned

…the cheapest thing in Butte…

Horace Smith, Hell With the Lid Off: Butte, Montana, New Bay Books, 2021. Kindle edition, p178

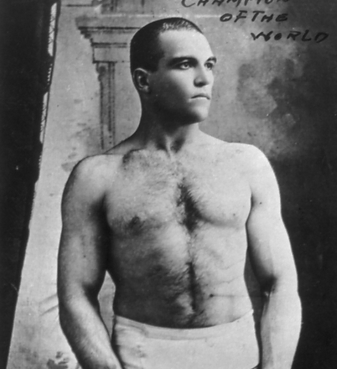

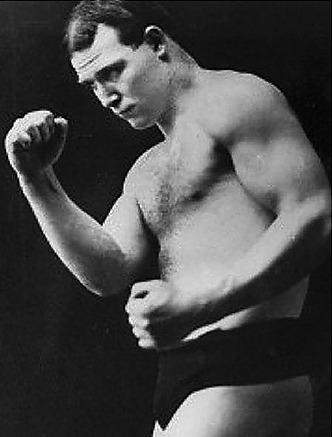

So ornery were Butte’s residents that, when World Heavyweight Champion James J. Jeffries breezed through in 1903, a local hardman challenged the man they called ‘The Boilermaker’ to an unofficial four-round exhibition bout (prizefights being of course illegal). Jack Munroe, or ‘Shagnasty’ as he was known8, not only went the distance with the Champ, but was awarded the decision by the referee as well. It remained the only blot on the formidable Jeffries’ record until his defeat at the hands of Jack Johnson in 19109.

(Of course, in the fight that really mattered, a rematch for the actual World Title in 1905, Jeffries beat Shagnasty Munroe to a quivering pulp inside of two rounds11.)

Shamrock City

With its abundance of gold, silver and copper mines, not for nothing is Butte known as the “Richest Hill on Earth”13. Rich maybe, but in Penrose’s era,

…Butte’s mines were among the most dangerous in the world.

David M. Emmons, “Immigrant Workers and Industrial Hazards: The Irish Miners of Butte, 1880-1919”, Journal of American Ethnic History, 5:1, 1985, p41-64.

For 1906-7, the mining fatality rate for Butte has been calculated at 5.3 per 1,000 men – the worst anywhere. Not only that, Butte’s death-rate for respiratory illness in 1916 was over 500 per 100,000 – twice the USA’s average. 277 miners died of such conditions that year; their average age was 4214. Horace Smith wrote that, at night,

…the smoke from the smelters would envelop the camp in a yellow vapor that produced violent fits of coughing.

Hell With the Lid Off: Butte, Montana, New Bay Books, 2021. Kindle edition, p84

Although people came from all over the world to work in Butte, the city was predominantly populated by first- and second-generation Irish men, women and children, and it was they who bore the brunt of Butte’s dangers15.

Adrift in a strange, hazardous land, the Butte Irish at least had strength in numbers, and a tradition of organisation and self-help. By the early 1880s, the Butte branch of the largely Catholic and nationalist Ancient Order of Hibernians had been established16.

A pro-Irish society projected a pro-Irish workplace. Studies have noted that, whilst the AOH and the more militant Clan na Gael took care of its members at home, these same members also campaigned for better working conditions through the auspices of the Butte Miners’ Union17.

Obviously, the Union had its work cut out. One of its more protracted campaigns was for the introduction of an eight hour working day, which would

…allow the miner to return to work refreshed and more alert in addition to reducing…the number of hours spent breathing the air three thousand feet below the surface…

David M. Emmons, “Immigrant Workers and Industrial Hazards: The Irish Miners of Butte, 1880-1919”, Journal of American Ethnic History, 5:1, 1985, p41-64.

This would not be realised until 191918. Of course, Butte’s Irish miners didn’t have a monopoly on their trade in the city. Cornish and English miners, along with other groups, competed for prominence too. Indeed, Butte’s two principal mine owners almost exclusively championed one nationality of workforce over the other.

And both men hated each other.

The Copper Kings

The two biggest cocks on Butte’s dunghill weren’t just interested in making money, though obviously both were extremely talented in this regard20. In the true traditions of America’s Gilded Age21, the activities and enmity of these two ‘Robber Barons’, Marcus Daly and William A. Clark,

…affected almost every aspect of the political and economic life of…Montana. Gigantic corporate mergers, the location of the state capital, the election of US Senators and Congressmen…

David M. Emmons, “The Orange and the Green in Montana: A Reconsideration of the Clark-Daly Feud”, Arizona and the West, 28:3, 1986, p225-245.

Daly was an Irish Catholic from County Covan, and a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians. The Irish nationalist and advocate of Home Rule, Charles Stewart Parnell, was a friend22. Unsurprisingly, Daly was known to give exceedingly preferential treatment to Irish Catholics in his mines. It was even rumoured that posters adorned the entrances of his establishments, bearing the following legend:

NO MAN OF ENGLISH BIRTH NEED APPLY.

Qtd from: David M. Emmons, “The Orange and the Green in Montana: A Reconsideration of the Clark-Daly Feud”, Arizona and the West, 28:3, 1986, p225-245.

Clark had a Scottish-Irish Presbyterian lineage, was a Grand Master Mason, and possibly may have been a member of the anti-Irish American Protective Association. His mines, on the main, employed Cornishmen; one such working was even nicknamed ‘The Saffron Bun’23.

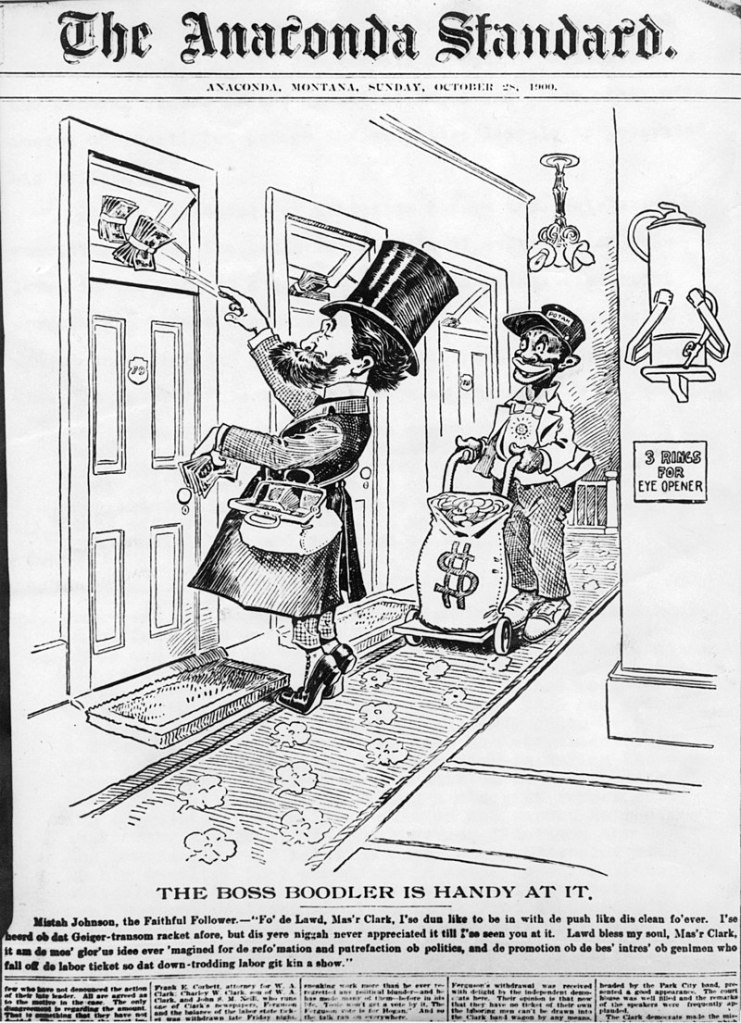

Daly devoted a lot of time, energy and money to keeping Clark out of the US Senate; Clark by contrast expended similar trying to get in. When it was revealed that Clark had bribed members of the Montana Legislature for their votes, Daly’s ‘paper, The Anaconda Standard, did not hesitate in lampooning him:

Naturally, Daly made sure his Standard was available on every Butte newsstand24. Clark used his own organ, The Butte Miner, to curry Irish favour and successfully promote Helena as the state capital of Montana – Daly of course wanted Anaconda25.

Clark also needed to allay suspicions amongst his Cornish workforce that he was going soft on the Irish – Cornishmen of the time being, as a rule, no great lovers of people from the Emerald Isle26. In short, his pro-Cornish credentials needed a boost.

Enter William J. Penrose.

‘Pen’

Penrose may not have been judged a man of “scholastic education”28, but he possessed many of the characteristics that make a good journalist: honesty, guts, tenacity, a good eye, and a way with words. That said, it may have been the very qualities he utterly lacked (diplomacy, humility, restraint) that made his newspaper, The Butte Mining Journal, a success.

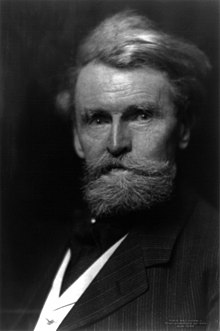

He must have also known what sold. In Gilded Age America, the most popular newspaper was The National Police Gazette, whose owner, Richard K. Fox (1846-1922), packed its lurid pages full of tales of sex, scandal, murders, more sex, fantastical achievements, and sports. The Gazette‘s contents changed the face of journalism, and made Fox a fortune29.

Like many others, Penrose took the hint. His ‘paper may have had ‘Butte’ on its masthead, but it was certainly national and popular in scope. For example, in 1889 Penrose travelled to Mississippi and covered the Sullivan-Kilrain boxing epic for his bloodthirsty readers back in in Montana – and doubtless had a high old time rubbing shoulders with the insalubrious sporting cognoscenti present31.

Penrose didn’t forget his roots either, and would have also been aware that Butte’s Cornish population was struggling for recognition under the dominant Irish culture. The Journal began to regularly feature a ‘News From Cornwall’ column, where the homesick Cornish of Butte could glean all the latest from Liskeard, or Tolgarrick32.

The Journal also regularly carried reports of local wrestling matches and tournaments, and was sure to keep its public in the know whenever an all-Cornish affair was in the offing – and what the stakes were33.

As well as reinforcing a Cornish identity in Butte, Penrose and his Journal sought to improve the status of his fellow Cousin Jacks and Jennies. When the pro-Cornish William A. Clark first ran for Senate – as a Democrat – in 1888, Penrose’s championing of his campaign has been accurately described by one historian as “sycophantic”34:

…Mr Clark is the superior of his competitor…so able a gentleman, so progressive a man, and so upright a citizen…

Butte Mining Journal, October 31 1888, p3

Penrose sounded the clarion-call for the Butte Cornish to get behind their principal employer in his bid for office. The Cornish must

…relieve themselves of a political thraldom…they are a mighty power…

Butte Mining Journal, October 31 1888, p3

But it was all for naught. Marcus Daly (like Clark, a Democrat) influenced the numerically superior Irish electorate (who, of course, largely worked for him) to vote Republican, something the Irish were rarely inclined to do35. Thomas H. Carter was elected, much to Penrose’s ire:

Lots of wind, but no honesty…As a promiser and gay deceiver Carter is a success…but…He has been tried and found wanting…

Butte Mining Journal, September 21 1890, p1

Daly, meanwhile, had

…sacrificed his principles upon the altar of policy…the Anaconda Standard…is…dishonorable in the extreme…trash…

Butte Mining Journal, January 18 1891, p4

Such utterances would not have gone unnoticed by the Butte Irish, Daly, or his employees at the Standard. But, for the time being, Penrose’s star was in the ascendant, especially among the Butte Cornish.

‘Pen’, as he was known in Butte36, became familiar to

…hundreds of men in Cornwall and thousands in Montana and other American mining camps…

Cornishman, July 2 1891, p7

Others from Cornwall making their way in the States sought him out. One such was Herbert Thomas (1865-1951), who was taken on as a stringer at Penrose’s Journal before returning home to edit the Cornishman for over fifty years37. He recalled Penrose as

…a great figure in those days…with his pungent pen…

Cornishman, May 1 1913, p4

Not that Penrose was all pungence and spleen. He could be kind-hearted and charitable39, with a soft-spot “for all mankind”40.

Penrose’s standing was such in Butte that he was voted onto the Montana State Legislature, as well as being elected President of the Butte Press Club41. Miners and working men of whatever creed must have thought they had someone to fight their corner in print, and in matters of government.

And then, in around early 1891, it all started to unravel.

Judas Penrose

Penrose’s chickens were coming home to roost. Two separate women with whom he had been recently involved had both allegedly pulled guns on the wayward reporter. One husband (that we know of) had also threatened to stab him43.

His most persistent paramour however was a lady known in Butte as Belle Browning, being euphemistically described as a “woman of the town”44. Her real name was Emma Turner, and she plagued Penrose – and his wife – in the months before his murder45.

She was known to have threatened to kill Penrose unless he left his wife for her – and her fearsome reputation ensured he took this seriously. Browning was not above disguising herself as a man in order to go about her nefarious business undetected, and would turn up, at all hours, in the Journal‘s offices, with

…a fiendish look in her countenance that did not betoken any good.

Butte Daily Post, June 18 1891, p4

Letters, by turn begging and menacing, came from her hand to Mr and Mrs Penrose. Unsurprisingly, Penrose sought solace in the bottle, and would cut a distressed figure in the streets.

What his good lady wife thought of all this is unknown, but she would have been aware that, in the event of her husband’s death, $10,000 insurance would have been paid out to her and their daughter46.

What made Penrose many more enemies than his roving eye, however, was his political stance on a crucial issue for Butte’s working class. In February 1891 the eight-hour day mining bill was brought before the Montana Legislature…and was defeated.

Mining magnates Clark and Daly both voted aye for the bill. Powerful men, they nonetheless appreciated the strength of the Butte Miners’ Union. Penrose, a Cornishman and one-time miner, inexplicably in the eyes of many, voted nay48.

The bill’s defeat caused outrage, and not just among Butte’s miners. Many other unions in the town expressed anger and solidarity. The naysayers in the Legislature were condemned in no uncertain terms, particularly those naysayers who had previously been on the miners’ side:

W. Judas Penrose deserves the contempt of all workingmen. As a professed friend of labor in the past his actions on the eight-hour bill will have placed him in his proper colors among the traitors.

Butte Weekly Miner, March 5 1891, p5

Why did Penrose oppose a bill ostensibly drafted to better the miners’ lot? Historians have suggested that, being raised in the Cornish tradition of contract- and tribute-mining systems, he would have seen the introduction of an eight-hour day as prohibiting to these methods49.

Being Cornish, Penrose would have also naturally bridled at what was an Irish-backed bill. Collapsing his Cornishness into Englishness, Penrose had founded in Butte the masonic order of the Sons of St George, in direct opposition to the varied, and dominant, Irish organisations50. They may have been in America, but many Cornish/English would have seen this as no reason to cease viewing the Irish as anything other than an inferior race51.

Something of the flavour of your typical ‘Sons’ gathering can be determined by a speech Penrose made at one such meeting, after he opposed the bill:

…we are Americans in the broadest sense of the word; but it must not be thought for a moment that we have ceased to respect, revere and love the land that gave us birth…for England’s traditions and honor among the nations of the world are something we are all proud of…

Butte Mining Journal, April 26 1891, p7

Evidently, ‘Ireland’ and ‘Irish’ were dirty words; the phrase ‘eight-hour bill’ must have been similarly verboten. Penrose’s seemingly illogical and immoral stance on the bill was under attack.

Not only was he slandered in the Press as ‘Judas’ Penrose, his own newspaper was subjected to a boycott by the Butte Miners’ Union. Through loss of readership and advertising revenue, his very own mouthpiece might wither and die.

Penrose, typically, came out fighting.

Penrose would have recognised the boycott as Irish-influenced53, and dismissed it as the

…lowest, meanest, most despicable instrument of malice that was ever imported…[an]…un-American principle…

Butte Mining Journal, May 10 1891, p1

He also vehemently defended his position, arguing that his denial of the bill was intended to protect the miners from themselves, stating that, while unions

…confined their efforts to legitimate work we stood by them, but when they began to interfere with the personal rights of others…we objected to their methods as un-American in principle…

Butte Mining Journal, April 22 1891, p4

And Penrose certainly thought some tenets regarding the enforcement of the eight-hour bill (were it to come to pass) to be draconian. In particular, the proposal that those found to be violating the rule (ie, working longer than eight hours), could face fines of up to $100 and possible imprisonment54.

But neither side would back down. In the Miners’ Union Hall was a large blackboard entitled ‘Traitors to Labor’: Penrose’s name was emblazoned for all to see at the very top of that list55.

For his part, Penrose cruelly satirised his enemies, publishing an eyewatering article on how Butte’s prostitutes (the “Chippies”) had supposedly formed their own Union. The fictional ladies bore names like “Madame De-The-Irish-World”, as well as the surnames of several prominent members of the Miners’ Union. At least one miner, Philip Hickey, was known to have taken particular umbrage56.

And maybe, just maybe, some thought Penrose had overstepped the mark.

Penrose received many threats and warnings. Perhaps the most chilling was written on a note found tacked to his office door:

3-7-77

This was the code of Montana’s vigilantes. It can be taken to represent the dimensions of a grave (3ft wide, 7ft long, and 77″ deep), or the length of time you had to get your keister out of town: three hours, seven minutes, 77 seconds58.

It may have been a prank. But not in Butte, Montana. Such things there are deadly serious. We all know what happened to Judas…

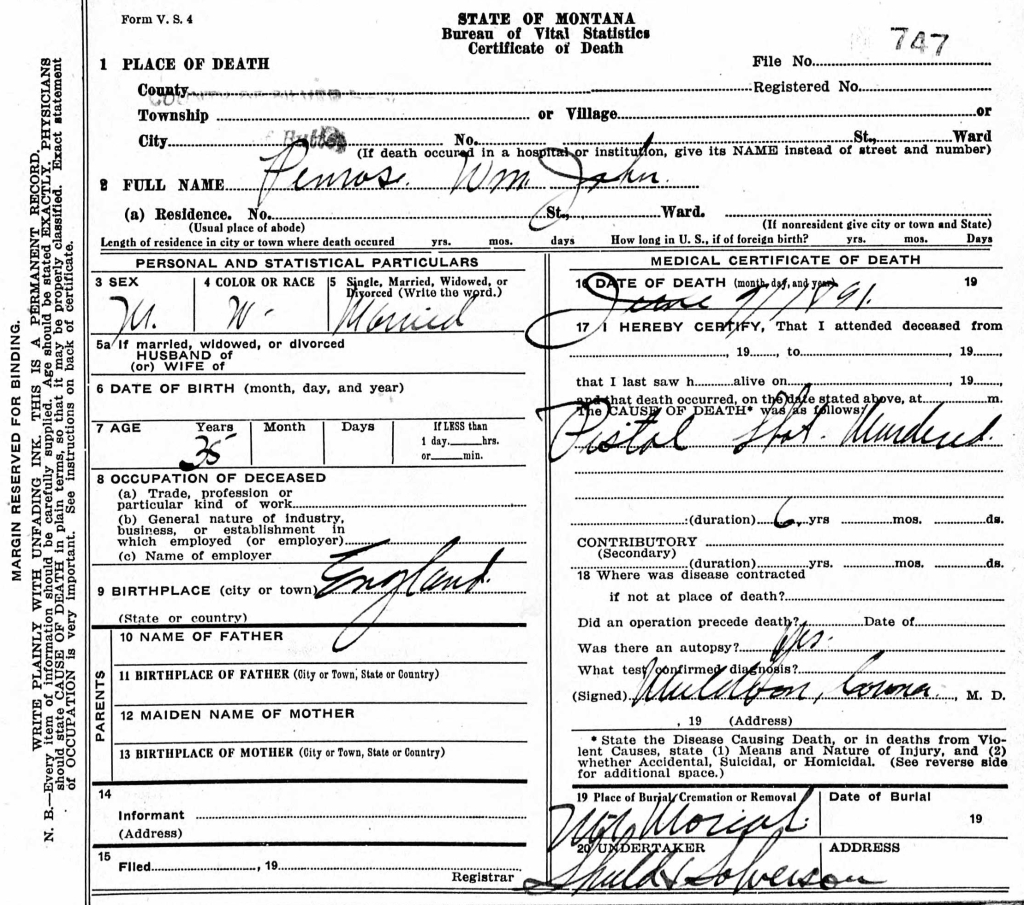

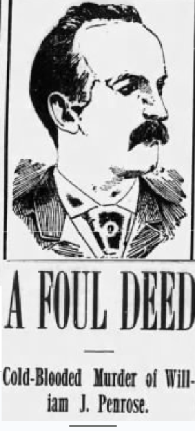

Penrose is killed

June 10, 1891 had just become June 11. Butte’s streets were coated in their customary sulphurous vapour. Penrose, three parts intoxicated and one part drunk, leaves his house to treat with some union agitators. En route, he bumps into a local man, Dan O’Donnell, and unburdens himself of his concerns for his life60.

150 yards from his home, he turns onto the corner of Montana and Galena. Three men, in black and wearing rubber-soled shoes, come at him through the smog. Penrose is coshed, or “sandbagged” unconscious. One of his assailants holds a revolver flush to the skull of the body prone on the sidewalk, and pulls the trigger61.

That’s all it takes. Penrose is dead.

O’Donnell heard the shot, but kept on walking. As he would later admit, the sound of gunfire, deadly or otherwise, was such an everyday part of life in Butte that, unless you were shooting (or being shot at), you paid it no mind62.

He paid more attention seconds later when three masked men loomed up behind him. A gun was waved in his face and he was ordered off the thoroughfare63. Shortly afterward, Penrose’s body was discovered, rendering Butte in a state of shock. Liked or loathed, everybody knew him, and the word spread like wildfire:

Penrose is killed…

Butte Weekly Miner, June 11 1891, p1

He hadn’t been robbed, and it didn’t take much inspired deduction to conclude that his murder had been

…the result of a personal grudge.

Butte Weekly Miner, June 11 1891, p1

Working on this assumption, in the early hours of June 11, the authorities arrested a near-hysterical Belle Browning in her bed. Witnesses stated a woman resembling her had been seen “hastening” along the sidewalk, only minutes after the murder64.

She was released for lack of evidence on June 24, and fades from our story65.

The Butte Press Club, and not the sectarian Sons of St George, made the funeral arrangements. Mrs Penrose insisted on this, stressing her late husband’s “cosmopolitan” nature66, and his pallbearers were all fellow journalists. The good, bad, ugly and rich (who may have been all three) of Montana attended, as Penrose had touched them all: 300 men, and over a hundred vehicles, came to pay their final respects. Until the disaster of 1895, it remained Butte’s largest funeral67. Indeed,

Those who had been counted his enemies and those who were his pronounced friends alike paid respect to the dead man…

Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5

Penrose was under the earth when the news broke in Cornwall, where he was remembered as a “sociable, bold, reckless and able man”68.

*

The murder of William John Penrose was a truly hideous, cowardly act. The nature of his passing did not sit well with the people of Butte:

Had he been killed in a fair fight or given any show whatever for his life…but the assassin’s act was so foul and fiendish…

Butte Mining Journal, June 14 1891, p1

That much was clear. Exactly who the culprits were – and it became rapidly apparent Penrose was the victim of a conspiracy – was less so.

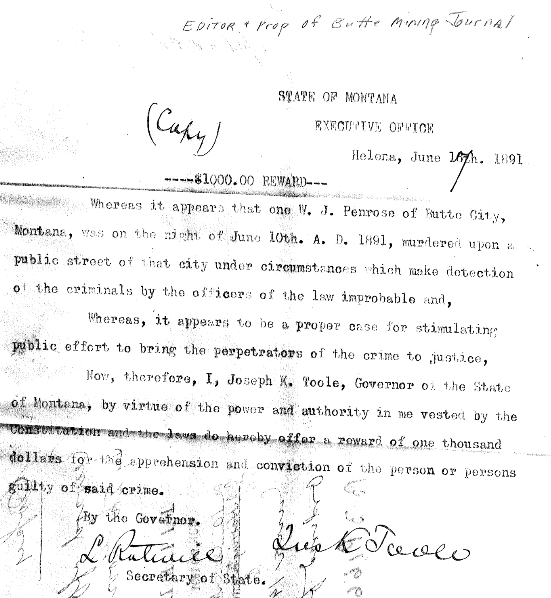

It was the Miners’ Union. It was a death-squad of vigilantes. It was hired hitmen from Indianapolis69. Find the killers, and you would find the person who ordered the killing. The Governor of Montana, Joseph Toole, posted a $1,000 reward, as did the Mayor of Butte and the Irish-born tycoon James A. Murray70.

But, for six weeks or so, there was not so much as a sniff.

Hang ’em high

In Butte, life went on. Philip Hickey left the subterranean life behind him to open a hotel in Boise City, Idaho71. Fellow lodgers and miners William Deeney and Eugene Kelly took in a new tenant, another miner called Ryan. Deeney and Kelly both found they had much in common with their new pal, and would often sample Butte’s nocturnal delights together, with Ryan regularly drinking to excess72.

In fact, Ryan was, as they say, peddling snake-oil. He was an undercover detective with the famous Pinkerton’s Agency, one of six such men in Butte hunting down suspects – and the fat reward – in the Penrose murder case73.

Hickey was arrested in Boise on July 26. Deeney and Kelly were taken the next day, en route to the Acquisition Mine. All had previously been linked to Penrose’s death, yet there was general bewilderment in Butte at them being hauled in74.

The men knew each other, having all held prominent positions in the Butte Miners’ Union back in 188875.

All three had been championed on their election by Penrose. Kelly had “more than average ability”, Hickey possessed the “respect and confidence” of his brother miners, and Deeney was one of “God’s noblemen”76.

But by 1891, matters were very different. For example, in Penrose’s eyes Hickey was only fit to

…smell into all the cesspools and sinks in the city…

Butte Mining Journal, May 24 1891, p1

By now being a fully-fledged member of the Sons of St George, he would have altered his opinions on Deeney and Kelly too, who were both of Irish parentage77. On hearing of Penrose’s death, Kelly had been heard to wish him in hell; Hickey was planning a retaliatory pamphlet to Penrose’s ‘Chippies’ article before he’d been killed78.

Dan O’Donnell, the last man to speak to Penrose and latterly come face to face with his probable killers, identified Hickey as one of the gunmen79.

All three were in Butte on the fatal night, ostensibly at a Union meeting80.

The weapon used to sandbag Penrose was a mining tool common in Cornwall known as a gouger. It was discovered to be the property of the Acquisition Mine, where Deeney and Kelly worked81.

Hickey, Deeney and Kelly were facing the rope:

…the guilty parties, whoever they are, will be convicted and hanged, for a more infamous crime never blackened the good name of a state…

Butte Daily Post, July 28 1891, p2

But the case was never brought to trial. After an arduous 41-day preliminary hearing, Hickey, Deeney and Kelly were released. There was not enough evidence to bring about a conviction83. They knew their names were connected with the crime, even if they were innocent, and had thus had ample time to prepare alibis84. Not only that, but several witnesses were demonstrated to be less-than reliable; some, like the Pinkerton detectives, failed to even testify85. Plus, crucial evidence had been found to be tampered with.

The gouger that knocked Penrose unconscious had, after its examination by the coroner, been entrusted to a police officer called Tom Waters. Waters was English, and a member of the anti-Irish Sons of St George. The coroner had found no mark on the gouger linking it to the Acquisition Mine but, mysteriously, the mark had appeared after Waters had had it in his care. Tellingly, Waters had also worked at the Mine, and would have known how its tools were etched86.

Only one man ever confessed to the murder of William John Penrose, and that wasn’t until 1893. A man calling himself Joseph McCormick gave himself up in Lake Crystal, Minnesota.

He gave the Marshal a fantastic story of Union conspiracy, secret societies, pro-Irish businessmen ordering Penrose killed, and a clandestine murder-meeting in which the triggerman was nominated by drawing a black ball from a bag.

McCormick, or whoever he was, then promptly escaped from jail, and his tale was dismissed as hokum87. Perhaps so. But Penrose was either simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, or he was the victim of a plot. We’ll never know.

Many thanks for reading, and with special thanks to Kimberley Kohn, Butte-Silver Bow Public Library, and Shannon Hopewell, Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives.

Follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

References

- 1861 Census, Ancestry.

- 1861 Census; Cornishman, July 2 1891, p7.

- Butte Weekly Miner, June 11 1891, p1. Herbert Thomas, who knew Penrose in Butte, wrote that he had once been a preacher and lawman in the Cornishman, May 1 1913, p4. Presumably, Penrose had told Thomas this himself.

- From: https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/montana/butte/

- From: https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/montana/butte/

- Shortly after Penrose’s untimely demise, another reporter, Horace Herbert Smith, came to Butte. By the time of his death in 1936, Smith had enjoyed a successful career as a New York journalist, hobnobbing with such literati as Zane Grey (Riders of the Purple Sage) and Upton Sinclair (The Jungle). His manuscript, entitled Hell With the Lid Off: Butte, Montana, was only recently discovered and published.

- From: https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/montana/butte

- Horace Smith makes reference to Munroe’s nickname in Hell With the Lid Off, p 205.

- From: https://www.montanapress.net/post/famous-and-not-forgotten-underdog-pugalist-jack-munroe. For more on the ‘Fight of the Century’ between Johnson and Jeffries, see Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson, by Geoffrey C. Ward, Pimlico, 2006.

- Both images are from: https://www.montanapress.net/post/famous-and-not-forgotten-underdog-pugalist-jack-munroe

- See: https://boxrec.com/wiki/index.php/James_J._Jeffries_vs._Jack_Munroe. Another noted slugger of the day who made his name in the backrooms of Butte’s bars was middleweight Stanley Ketchel – ‘The Michigan Assassin’. See: https://boxrec.com/wiki/index.php/Stanley_Ketchel#Early_Years

- Image from: https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/montana/butte/

- Butte produced more mineral wealth than any other mining district in the world up to the middle of the 20th century. At time of writing, over $48 billion dollars of wealth have come up out of the ground in Butte. From: https://westernmininghistory.com/towns/montana/butte/

- From “Immigrant Workers and Industrial Hazards: The Irish Miners of Butte, 1880-1919”, by David M. Emmons, Journal of American Ethnic History, 5:1, 1985, p41-64.

- In 1900, the Irish population of Butte was over 17,000 out of a total of 47,000 – 36%. 5,300 of that Irish total were working men, and of them, nearly 3,600 or 68%, were miners. From: “Immigrant Workers and Industrial Hazards: The Irish Miners of Butte, 1880-1919”, by David M. Emmons, Journal of American Ethnic History, 5:1, 1985, p41-64.

- From: “Immigrant Workers and Industrial Hazards: The Irish Miners of Butte, 1880-1919”, by David M. Emmons, Journal of American Ethnic History, 5:1, 1985, p41-64.

- See David M. Emmons articles: “Immigrant Workers and Industrial Hazards: The Irish Miners of Butte, 1880-1919”, Journal of American Ethnic History, 5:1, 1985, p41-64; and “The Orange and the Green in Montana: A Reconsideration of the Clark-Daly Feud”, Arizona and the West, 28:3, 1986, p225-245. Butte was, is, a union town. Besides the Miners’ Union, in Penrose’s day there was the Workingmens’ Union, the Clerks’ Union, the Typographical Union, and the Cooks and Waiters’ Union, who were nicknamed ‘The Hashers’. From the Butte Mining Journal, March 4 1891, p4, and Horace Smith’s Hell With the Lid Off, p121.

- See Robert Whaples, “Winning the Eight-Hour Day, 1909-1919”, Journal of Economic History, 50:2, 1990, p393-406.

- Images from their respective Wikipedia entries: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcus_Daly; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_A._Clark

- For example, on Clark’s death in 1925 his estate was estimated at $300 million, the equivalent to $3.7 billion in 2021. This makes him one of the wealthiest Americans ever. From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_A._Clark

- The Gilded Age was a “period of gross materialism and blatant political corruption in U.S. history”. For a brief explanation of this epoch, see: https://www.britannica.com/event/Gilded-Age

- For more on Parnell’s life and career, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Stewart_Parnell

- Both Clark’s and Daly’s backgrounds are surveyed in: David M. Emmons, “The Orange and the Green in Montana: A Reconsideration of the Clark-Daly Feud”, Arizona and the West, 28:3, 1986, p225-245.

- Horace Smith, Hell With the Lid Off: Butte, Montana, New Bay Books, 2021. Kindle edition, p96-7. Smith was an employee at Daly’s Standard; even when he wrote Hell With Lid Off in the 1930s, his praise of Daly remained absolute (although the man died in 1900), and his dislike of Clark all-encompassing.

- Smith, Hell With the Lid Off, p113-7.

- For evidence of anti-Irish feeling amongst the Victorian Cornish, see: Louise Miskell, “Irish Immigrants in Cornwall: the Camborne Experience, 1861-1882”, in Roger Swift and Sheridan Gilley (eds.), The Irish in Victorian Britain: the Local Dimension, Four Courts Press, 1999, p31-51. A Camborne rugby player of the early 1900s, Tom Morrissey, endured such heckling from Redruth fans regarding his Irish parentage that he bared his arse to them on the pitch. See my post which details the event here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/09/02/camborneredruth-the-oldest-continual-rugby-fixture-in-the-world-part-one/

- From: Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America’s First Sports Hero, by Christopher Klein, Lyons Press, 2015, p145-171. I mentioned earlier that prizefights were illegal in Gilded Age America; the Mississippi authorities did indeed attempt to call a halt to the brawl. The local Sheriff climbed into the ring before the first bell, proclaimed the lawlessness of what was about to ensue, accepted his $200 bribe, and settled down on a ringside seat (doubtless with a bottle of forty-rod for company) to enjoy the action.

- Butte Weekly Miner, June 11 1891, p1.

- See: Liam Barry-Hayes, “Richard K. Fox and His National Police Gazette“, History Ireland, 28:1, 2020, p26-8. Irish-born Fox loved boxing, yet hated John L. Sullivan, whose parents hailed from Kerry and Westmeath. The Sullivan-Kilrain grudge-match of 1889 was engineered, in the main, by Fox himself. For more on their feud, see Strong Boy: The Life and Times of John L. Sullivan, America’s First Sports Hero, by Christopher Klein, Lyons Press, 2015.

- The image of Fox is from: “Richard K. Fox and His National Police Gazette“, History Ireland, 28:1, 2020, p26-8; the Gazette image is from: https://policegazette.us/

- Butte Mining Journal, July 10 1889, p1.

- Butte Mining Journal, April 22 1891, p1.

- For example, Butte Mining Journal, July 10 1889, p1, and February 4 1891, p4. Of course, if you wish to know more, see Cornish Wrestling: A History, by Mike Tripp, Federation of Old Cornwall Societies, 2023.

- David M. Emmons, “The Orange and the Green in Montana: A Reconsideration of the Clark-Daly Feud”, Arizona and the West, 28:3, 1986, p225-245.

- David M. Emmons, “The Orange and the Green in Montana: A Reconsideration of the Clark-Daly Feud”, Arizona and the West, 28:3, 1986, p225-245.

- As noted in the Cornishman, April 28 1892, p7.

- Cornishman, May 1 1913, p4. Thomas’ obituary is given in the West Briton, December 20 1951, p6.

- As observed in The Butte Miner, May 8 1888, p4.

- Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5.

- Image from: http://www.artuk.org/artworks/the-man-in-the-panama-hat-herbert-thomas-editor-of-the-cornishman-15048. Thomas recalls his experiences as a spectator of wrestling in the Cornish Post and Mining News, August 17 1935, p4.

- As noted in the Butte Mining Journal, June 14 1891, p1; and the Butte Weekly Miner, June 18 1891, p3.

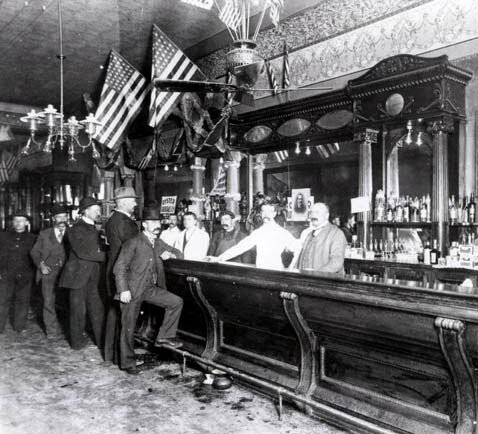

- Image from: https://www.verdigrisproject.org/butte-americas-story-blog/butte-americas-story-episode-222-the-atlantic-bar

- Butte Weekly Miner, July 2 1891, p7.

- Butte Mining Journal, June 14 1891, p1.

- Butte Weekly Miner, June 11 1891, p1.

- From Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5; Butte Mining Journal, June 14 1891, p1; Butte Daily Post, June 18 1891, p4; Butte Weekly Miner, July 2 1891, p7.

- Image from: https://www.distinctlymontana.com/tycoons-petticoats. Prostitution was big business in Butte.

- Anaconda Standard, February 12 1891, p4.

- See: Zena Beth McGlashan, Buried in Butte, Wordz and Ink Publishing, 2010, p231-4.

- See: Zena Beth McGlashan, Buried in Butte, Wordz and Ink Publishing, 2010, p231-4.

- UK Government policy had of course helped to shape this view. See: David Cannadine, Victorious Century: The United Kingdom, 1800-1906, Penguin, 2017, p11-58.

- Image from: https://buttehistory.blogspot.com/2014/11/cricket-in-butte.html

- See David M. Emmons, “The Orange and the Green in Montana: A Reconsideration of the Clark-Daly Feud”, Arizona and the West, 28:3, 1986, p225-245.

- Butte Mining Journal, May 17 1891, p1.

- Butte Weekly Miner, September 24 1891, p3.

- Butte Mining Journal, May 3 1891, p1; also mentioned in: Zena Beth McGlashan, Buried in Butte, Wordz and Ink Publishing, 2010, p231-4. Hickey’s reaction to the Chippies article is from the Butte Weekly Miner, September 24 1891, p2.

- Image from: https://southwestmt.com/blog/what-on-earth-does-3-7-77-mean/

- Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5; Butte Mining Journal, June 14 1891, p1; Butte Daily Post, June 18 1891, p4. The meanings behind ‘3-7-77’ is from: https://southwestmt.com/blog/what-on-earth-does-3-7-77-mean/

- Image from: https://westernmininghistory.com/1527/total-devastation-the-butte-montana-explosion-of-1895/

- Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5.

- Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5; Butte Weekly Miner, June 11 1891, p1. The phrase ‘sandbagged’ is Herbert Thomas’ description of how his friend was waylaid, from the Cornish Post and Mining News, August 17 1935, p4.

- Butte Daily Post, August 12 1891, p4.

- Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5.

- Anaconda Standard, June 11 1891, p5; Butte Mining Journal, June 14 1891, p1.

- Butte Weekly Miner, July 2 1891, p7.

- Butte Weekly Miner, June 18 1891, p3.

- Butte Mining Journal, June 14 1891, p1.

- Cornishman, July 2 1891, p7.

- Butte Mining Journal, June 17 1891, p2; Butte Daily Post, June 18 1891, p4; Butte Weekly Miner, June 18 1891, p4.

- Butte Mining Journal, June 14 1891, p1; Butte Daily Post, June 18 1891, p1, and July 3 1891, p1. For more on James Murray, see: https://www.dib.ie/index.php/biography/murray-james-andrew-a10263

- Butte Weekly Miner, July 30 1891, p5.

- Butte Daily Post, July 28 1891, p4.

- Butte Daily Post, July 27 1891, p4. For more on the Pinkertons, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pinkerton_(detective_agency)

- Butte Daily Post, July 27 1891, p4.

- Butte Mining Journal, March 7 1888, p4.

- Butte Mining Journal, March 10 1888, p4.

- 1900 US Census, Ancestry.

- Butte Daily Post, August 21 1891, p4; Hickey’s reaction to the Chippies article is from the Butte Weekly Miner, September 24 1891, p2.

- Butte Daily Post, August 12 1891, p4.

- Butte Weekly Miner, July 30 1891, p1.

- Butte Daily Post, August 13 1891, p4.

- Image from: https://www.mtmemory.org/nodes/view/75421

- Butte Weekly Miner, October 8 1891, p6.

- Butte Daily Post, July 27 1891, p4.

- Butte Daily Post, August 20 1891, p4. One witness pointed to Hickey in the dock, when he believed he was identifying Kelly. The Butte Weekly Miner of August 13 1891 (p1) noted that, when their turn to to be called came, the Pinkertons’ were already a hundred miles away from Butte.

- Butte Daily Post, August 14 1891, p4; Butte Weekly Miner, September 24 1891, p2.

- From the Anaconda Standard, October 26 1893, p1; Neihart Herald, November 4 1893, p1; Daily Appeal, November 7 1893, p3.

- Image from: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/98643953/william-john-penrose

<

div>Nice piece Francis. I was particularly interested as my grandfather went to Butte

LikeLike

Cheers. What years was he there?

LikeLike

1904-1913.

<

div>

Nick SerpellSent from my iPad

<

div dir=”ltr”>

<

blockquote type=”cite”>

LikeLike