Reading time: 30 minutes

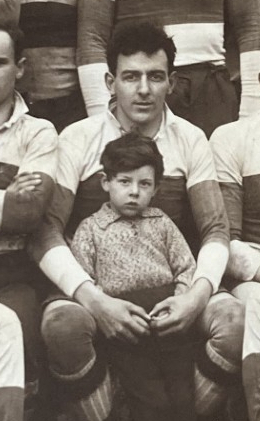

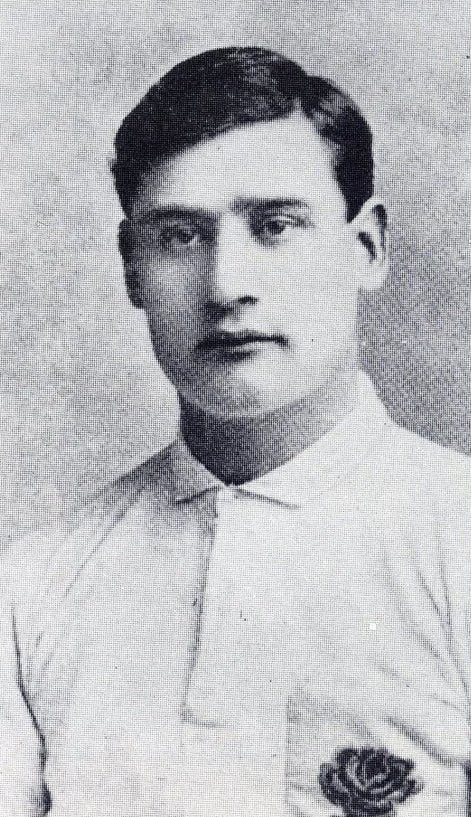

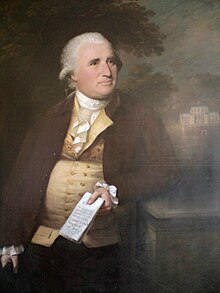

He’ll play at Lord’s one day… ~ an unidentified sage appraises a young Penberthy at the home of cricket in 1972

…it’s not all glamour, and it’s not all good… ~ Tony Penberthy gets real

Cornwall’s First Class cricketers

Since the 1970s, there haven’t been many Cornish cricketers who have broken through to play professionally with a First Class County XI. If memory serves, for the men there’s been Mike ‘Pasty’ Harris, Malcolm Dunstan, Michael Bryant, Jack Richards, Malcolm Pooley, Piran Holloway, Ryan Driver, Tim and Neil Edwards, David Roberts, Carl Gazzard and Charlie Shreck. For the women, it’s Laura Harper, Emily Geach and Rebecca Odgers. Apologies if I’ve left anybody out.

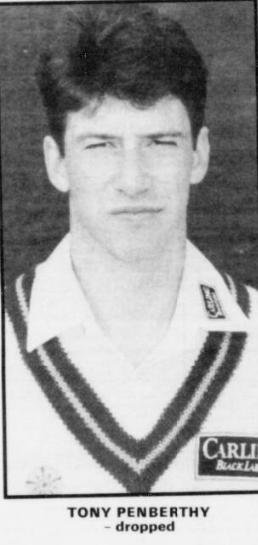

When I was watching cricket on TV in the 1990s (this was when domestic cricket was shown on terrestrial television, long before anyone had thought of The Hundred), a Cornishman regularly featured for Northamptonshire. And he was good. He bowled at a decent pace, he was a sharp fielder and he went for his shots. A Cornishman was holding his own against some of the biggest names in world cricket. The commentators invariably made a hash of pronouncing his surname, with no emphasis on the second syllable.

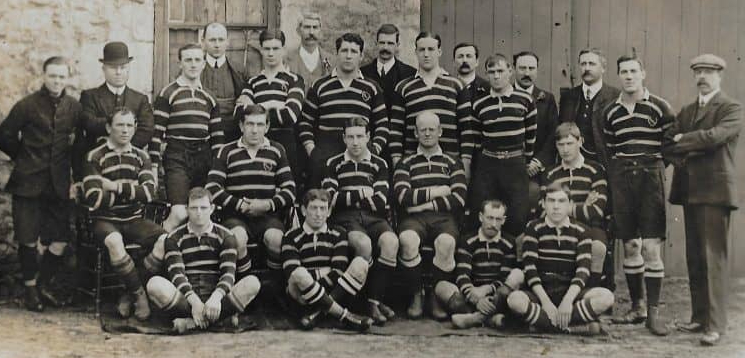

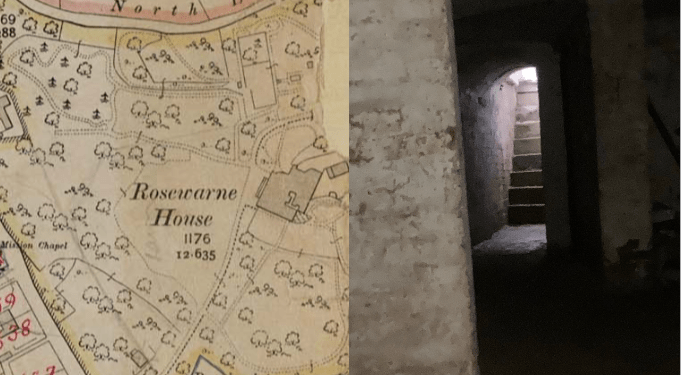

The cricketer in question was Tony Penberthy, from Troon. Penberthy. A man who excels at pretty much any game you care to mention, it was cricket that was always going to win out. As a three-year-old in 1972 he was present at Lord’s when Troon won the inaugural Haig Village Knockout Cup.

Already mad keen on the sport, Tony would wear his own whites and patrol the boundary, hoping the ball would come his way. After the match, whilst playing with some other lads by the Tavern, Tony’s mum, Wendy, was told by an onlooker that

He’ll play at Lord’s one day…for me, luckily, it came true.

That said, initially another sport took precedence:

I would honestly say that football was my first love. I think I was probably still at primary school when Plymouth [Argyle] showed an interest. There was a scout who was at Trewirgie School, but obviously in those days there was no football academies or stuff like that, and I was far too young to go for a trial. So as far as signing me goes, that was never anywhere near!

Argyle got round to inviting Tony for a trial when he was 14, but he was already spending Easter and summer holidays with the Northants cricket squad:

I realised when I came to Northampton and spent two weeks playing and training with the first team, that was the life for me.

Committing to one sport professionally didn’t mean abandoning the other. Even Ian Botham still found time to turn out for Scunthorpe United, and like Beefy, Tony found time to play for Troon AFC. His parents were heavily involved with the club; spending winter playing soccer and seeing his old mates was the ideal salve after a hard summer’s cricket.

It was also good for me to have a break from the cricket. I was also only on a six-month contract, so there was nothing the club [Northants] could do about it! Loved those times. It was always good to come home and play a bit of sport.

Cornwall Schools, England Schools

Tony was also fortunate that his secondary school encouraged and nurtured sporting prowess:

I think we were very lucky at Camborne School at the time. We had three male PE teachers, there was Pip [Tuckey], Roger Randall and Andy Dawe. They were great! If you loved your sport, they would encourage you and work with you all the way. I felt very lucky.

Tony’s parent club were no slouches where youth development was concerned either. Youngsters were always being encouraged in an atmosphere of success.

Troon had U13s and U16s ever since I can remember; I think I played in the U13s when I was about 9…Monday nights was junior coaching at Troon and it was always busy.

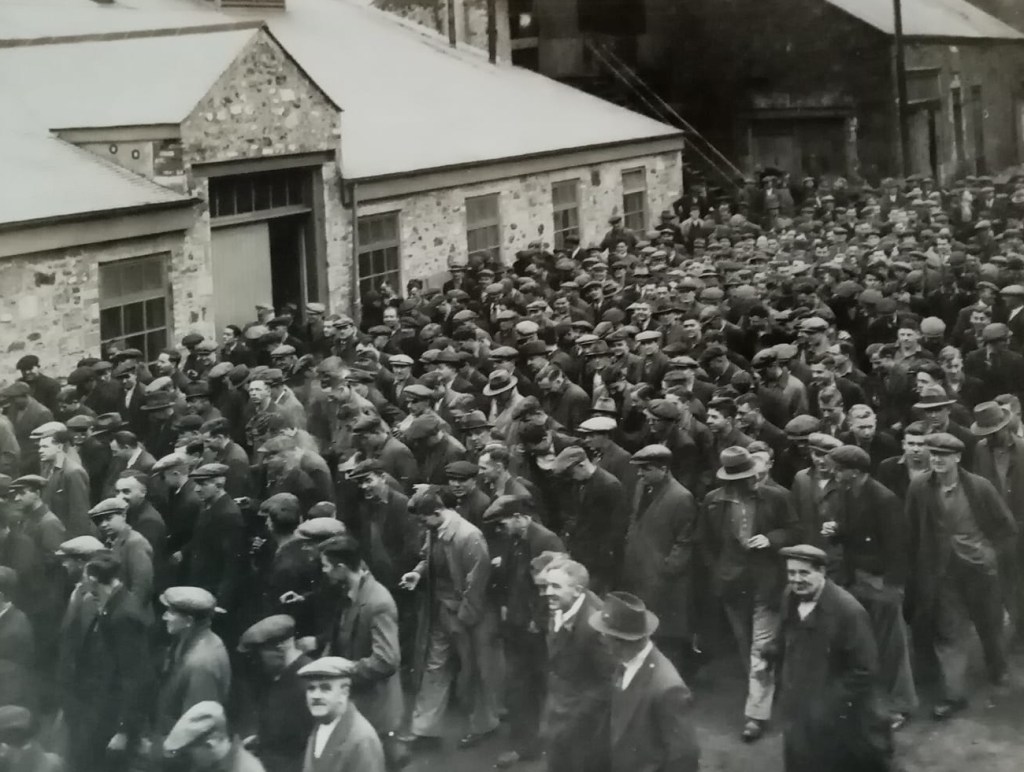

I think because of the success that Troon had had in the village competition, you know, it went through the village, and beyond, I think, winning a national competition…but for us kids, you know, it was just football and rugby in the winter, and cricket in the summer!

For all that, Tony’s introduction to senior cricket was not with Troon. Gerald, his dad, was finishing his playing days with Holmans, and Tony would turn out for their Second XI. Don’t think for one second he was there to make up the numbers. At the age of 12, he was bowling 24 overs against Camborne, and would strive to bowl out Pip Tuckey when playing Penzance2.

He was shortly registering for Troon, though – Tony was too good an asset to lose. To be sure, players in their early teens aren’t normally in such high demand for senior XIs. Tony’s talent must have been prodigious, and not just as a bowler:

My dad always said to me, if you’re batting and you’re bowling, you’re always in the game. If you don’t get any runs or you don’t bowl well, you’ve always got a second bite of the cherry, really. And he was right.

It definitely got me into teams, because of the fact that I could bat, bowl and field. Back in the day, when I started [for Northants], you could possibly get away with being a bowler who couldn’t field; nowadays and towards the end of my career, you had to be a two-dimensional cricketer, at worst. If you were a bowler, you had to be able to field, else you just stuck out like a sore thumb. If you can’t field to an adequate level, it’s not acceptable, and it can cost you your place.

It was the best advice my dad ever gave me, to always be in the game. It was always good to have an opportunity to make an impact on the game, one way or the other.

I always think batting was my strongest suit though. But it was ironic that bowling got me in the first team at Northants, you know, the fourth seamer who could bat…

Tony had the dedication to back up his ability. Coaching books would be devoured. Boxes of balls would have their seams chalked (Tony wanted to make sure the ball left his hand correctly) and be carted down to the nets. He was 14, and wanted to get into the England Schools XI. ‘I was always very driven’, he told me.

Northamptonshire started taking an interest in Tony at this point, yet it wasn’t down to his performances in any schoolboy representative XI. A coaching course on a family holiday at Butlin’s led to Tony being invited to a more prestigious course at Clacton. His performance and attitude there got him two days at the MCC indoor school at Lord’s. There, he won Boy of the Year:

One of the Butlin’s and MCC coaches, John Malfait, was a Northants man and passed Tony’s name on. Impressing in a county schoolboy match, Tony was invited up for a trial. He tuned up for this by scoring 140 for Cornwall U15s, then presented himself at The County Ground on Abington Avenue:

I walked into the changing room, and there was all these kids, 19, 20, I thought I’d got the wrong day! I was only 14 and not very big in those days. They said to me I was to come back in April for two weeks, and that’s basically what I did for Easter and summer holidays whenever I was available. Made my debut for Northants Seconds when I was 15. When I was 16, I was up for four or five weeks in the summer…

They really looked after me, I was billeted out to a family who couldn’t do enough for me. Really exciting time for me as a young person to be experiencing that kind of…you know, it was great!

It might be an old saw, but it’s certainly applicable in Tony’s case: talent always comes through. Tony didn’t just need to be good. He needed to be exceptional. Children from state schools are at a massive disadvantage compared to public schoolchildren when it comes to progressing in sport, especially cricket, and it’s getting worse. As there are very few public schools in Cornwall, the gulf is less pronounced and children are, by and large, on a level playing field. The further upcountry you go, and further up the cricketing ladder you climb, the more you discover that where you schooled matters as much as how you play a cover drive4.

When we went as the West of England squad to the England Festival, the majority of [my team] were either from Millfield or Taunton. And then when I got into the England Schools set-up, there was probably only two or three of us in that England team that went to a Comprehensive. All the rest were from private schools.

I think it’s sad, cricket’s not coached enough, I think it’s all left to clubs, a lot of clubs have really strong junior set-ups. It seems to be an elitist sport, and private schools seem to benefit. It’s very much the way it is.

I remember…I think we were at the England Festival, at Hull, and I got some runs against the Midlands, my mum overheard two men talking, ‘I wonder which school this boy goes to..?’ My mum just turned around and said, ‘What does it matter?’

Unfortunately, whether we like it or not, the responsibility’s gonna fall on clubs, and build a relationship with local schools, that the schools can always push a child somewhere. It’s not an ideal situation, but thankfully I think a lot of clubs are doing the best they can to give kids the opportunity to play cricket.

Speaking of clubs, in August 1983 Tony made his First XI debut for Troon, in Senior One (West)5. Trust me, this is the best cricket in Cornwall:

I thought at the time I was probably just gonna make the numbers up! It was against Helston and we fielded first. Just before we went out to field, Terry Carter said to me, ‘First over at the top hedge?’ So I got the new ball!

It was a really great opportunity for me. Christ, you don’t get any better than that! It would have been easier [for Troon] to pick someone older in the Second Team, but for me it was dream come true! Ever since I was a kid it was all I could think about, they were my heroes, I could never ever see much further than playing for Troon First Team, so to do it so young was fantastic.

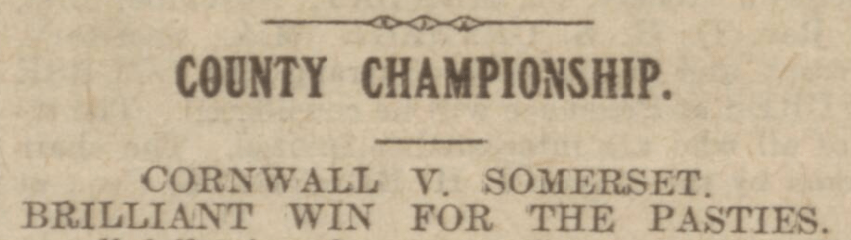

Tony wasn’t the only talented youngster in Cornish cricket at that time. Aged 16 in 1986, he made 41 for Troon First XI. For Camborne, that same week, another 16-year-old called Malcolm Pooley made 118 against Holmans. If Tony could take a hat-trick against St Just, Malcolm could notch up a ton against Penzance. To look back on these reports, it’s almost like the two teenagers were trying to out-wow the other6.

Malcolm signed professionally for Gloucestershire at the same time as Tony went to Northants (1988-89). In the 1990s he was Camborne’s star player, scoring runs for fun and forming a fearsome new-ball partnership with a tearaway fast bowler, Paul Berryman.

Me and Malcolm played a lot of Cornwall Schools together, we played for England South in an international tournament in Belfast…and won it! But there was rivalry as well, let’s be honest here, it was Camborne and Troon!

But I’d like to think that, with Malcolm and myself, we encouraged each other and pushed each other to get better. There’s not many Cornish lads that go on to play professional cricket, and when you’re out there you look out for each other, and hope that you’re all getting on and doing well.

When he went back to Camborne, it was sad, to be honest, because he’d done so well at Gloucester. Malcolm will always have my respect, he was a very very fine cricketer.

Northamptonshire professional

With such a long immersion in the culture of professional cricket, Tony had no qualms about signing for Northants on a two year contract when he turned 18. This was extended after his first year, and he made his First Class debut a year later. But he still had a lot to learn:

When you play professionally, the bowling’s a little bit quicker, the batsmen hit it a little bit harder. The fielding…that for me is probably the biggest difference. The speed to the ball, and the anticipation. The really good fielders, they’re half-a-yard there already, whereas in club cricket sometimes people are sleeping, thinking ‘bout what they’re gonna do later.

That and the fact that there’s less bad balls, and mistakes just get punished. You bowl a bad ball in First Class cricket, invariably it’ll go for four. You might get away with it in club cricket.

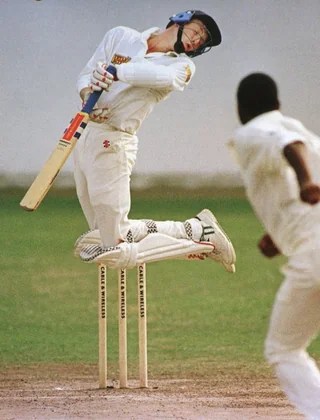

Tony made the dream debut. In June 1989 he was picked to play the touring Australians:

I had Mark Taylor, the captain, first ball, then Geoff Marsh, the other opener, and Dean Jones. Pretty good – missed Allan Border though, that was the only thing!

Taylor played over 100 Tests for Australia, and both Marsh and Jones were 1987 World Cup winners, though Jones is perhaps best remembered for his near-mythical 210 against India in 19867. Tony returned figures of 3 for 56 off 15 overs, and must have been well pleased with his work. But cricket has a way of coming back to bite you. Batting in his first innings, Tony had to face up to Merv Hughes, a walrus-moustached bear of a man who classed all batsmen as prey. Second time round he met Terry Alderman, who wasn’t as quick but had bucketloads of skill8:

Wicket with my first ball, then a pair! The highs and lows of First Class cricket! Obviously that was my first exposure to these international cricketers…I was really unlucky the first innings, I just went to turn one off my hip, and I got a little nick, hit my thigh pad, bounced up, and David Boon was there at short leg. Second innings, I think I was LBW…well, many people have been ‘LBW, Alderman’ in their career, really!

But, y’know, if someone had said to me, you’ll get a pair, but you’ll take a wicket with your first ball, I think I would have taken that, against Australia!

First Class all-rounder?

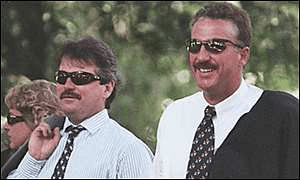

The highs and lows…listening to Tony talk about his career reminds me in many ways of Simon Hughes’ award-winning 1997 cricketing tell-all, A Lot of Hard Yakka. If you want further insight into the life of a professional cricketer, go there. Tony initially struggled to secure a regular First Team spot, the local press labelling him early on as a one-day specialist9. Northants’ all-round kingpins at the time were David Capel, a man good enough to play 15 Tests for England and be hailed as the next Ian Botham, and Kevin Curran, a Zimbabwean who represented his country at the 1983 World Cup.

Those two guys were top quality performers. And also, extremely fit guys. I think for me, seeing these guys operate, seeing what they did, that was good for me as a young player coming through.

It’s one of those things people don’t appreciate about professional sport. It’s bloody hard. It’s hard, just doing your skill sets, batting and bowling against the best players in the world. But then, obviously, you’ve got to manage the disappointments. Whether it’s injury, or lack of form, or lack of opportunity, they all come along at some point in your career.

But you’ve got two options. You either give in, or you deal with it. I did get categorised early on as a one-day player, because I could bat-bowl-field, and if you can do those three disciplines pretty well, you’re an asset to any one-day team.

Tony could score 130 and take two wickets for the Second XI, yet had to feed off scraps when promoted to the First XI11. You have to admire his resilience:

It was hard for me at the beginning, because I was batting in the top three in the second team, and sometimes opening the bowling, sometimes first change. So then when you come into the first team, you’re batting at seven or eight, and in those days it was three-day cricket. So if your team went well in the first innings, you might be going in with not many overs before you were going to declare.

I just felt it was quite hard for me to promote my batting at that time, I probably didn’t do myself justice. I probably should have scored more runs, but on the other hand the opportunity was not always there, batting that low down in that kind of cricket.

Thankfully later on in my career I was batting further up the order and got more of a chance to prove myself, really.

County Cricket in the 1990s

When Tony talks about the best players in the world, he isn’t kidding. Every County XI in the early 1990s could boast one or more international stars:

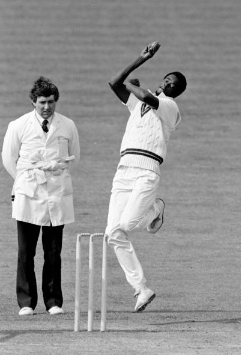

[Northants] was a very strong side. When I made my debut we had nine internationals. We had some really good overseas players, we had Winston Davis and Curtly Ambrose, and in those days you could have two overseas players and you could alternate them.

So…you could find yourself playing Lancashire Second XI, we had Ambrose, they had Patrick Patterson! Having that lessened your workload, obviously, but it really raised the standards of second team cricket.

Patterson was lightning…I can vouch for that! I opened the batting when we played him, second innings the game was pretty much dead, and he bowled four overs at the beginning, probably at three-quarter pace. Then he bowled me a full toss and I hit him for four. And I was probably strutting down the wicket a bit…

…the next ball hit my shoulder before I’d moved, and he looked at me as if to say, look, if you really want me to try…

There was some quick lads around and, on their day, if they got it right…it’s very difficult to say who was the quickest. I faced Shoaib Akhtar at Northampton on a slow one and he was still very very quick. Waqar Younis, Wasim Akram, Malcolm Marshall…top top performer. Then we had Greg Thomas13 early on in my career, who was touted to be the fastest white man on the planet, and when he got it right, he could really get it through.

In other words, even in a second team game you could be facing the fastest, nastiest bowlers on earth. Every team had one, and Northants had Curtly Ambrose, who was fearful to watch, even on television. Behind the scenes, though…

He was a totally different person. He didn’t like talking to the media. It wasn’t that he thought he was better than anyone else, he just didn’t feel comfortable. But with us, in the dressing room, he was great. He was always joking around, always funny, loved his music…what a person to have in your team! What a performer! I found him nothing but good value, really, and I travelled with him a few times in the car, and he was very supportive of us as a bowling unit.

To counter Ambrose’s complaints about dropped catches in the slips, Allan Lamb moved the big man himself to that position, and to have Curtly Ambrose geeing you on from the cordon was manna to Tony.

Allan Lamb knew how to socialise as well and moved in circles beyond the reach of mere cricketing mortals. Thanks to him, Tony’s 21st birthday was celebrated at Peter Stringfellow’s London nightclub. Let’s just say, their names were down.

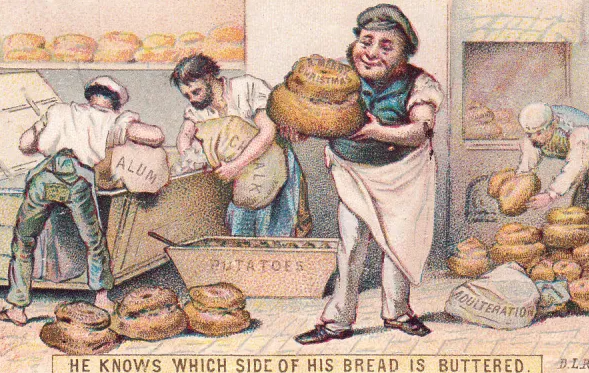

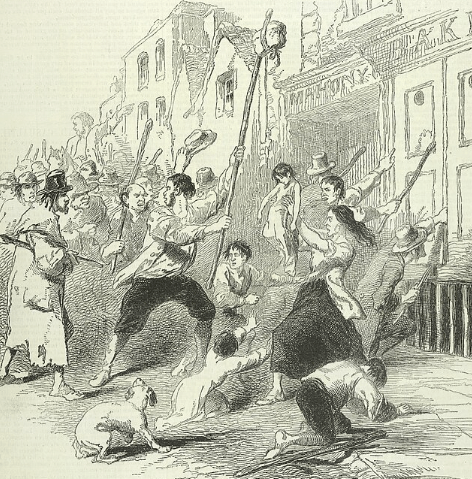

Clearly the Northants changing room was a lively one, but some subjects were taboo. Lamb’s involvement with Ian Botham in the highly publicised and highly expensive ball-tampering scandal of the early 1990s was a place where his Northants team did not go. It was his money, Tony told me, so you let him spend it.

Lack of first team opportunity early in his professional career was offset by Tony’s working relationship with the coach, Mike Procter. An all-action South African all-rounder, on his country’s isolation from international sport in the 1970s he joined Gloucestershire, his exploits for the county being such it was nicknamed ‘Proctershire’15. His laid back, self-expressive approach to cricket helped Tony settle in.

Plus, on occasion Tony could count on a familiar face from Cornwall. David Roberts, a fellow Troon boy, joined the club in 1996. In 1991 the West Indian all-rounder Eldine Baptiste joined Northants, and led the averages with 49 wickets. He had previously played Cornish cricket for St Gluvias, and is arguably the fastest, most terrifying bowler seen in Cornwall to this day16.

He was great with us young guys! He would give us loads of advice, but also he loved coming out and having a beer with us on Friday nights. We used to go into town, ring him up, ‘Eldine, we’re going into town…’ It could be your first year on the staff or you could be Allan Lamb, he was just the same with everyone. Really, really good.

Some reminders of the West Country in professional cricket though were less welcome. Warwickshire had a pugnacious batsman at the time called Roger Twose, who was born in Torquay. Eventually he played test cricket for New Zealand and is currently the Director of New Zealand Cricket17. What he called Tony in a match where Tony was batting was so bad Tony complained to the umpire; I’ll refrain from printing the actual words here. But I will reproduce Tony’s response to Twose:

If you ever say that again, I’ll beat this bleddy bat ‘round your ‘ead!

Meanwhile, David Capel and Kevin Curran practically took Tony under their wing:

There was always encouragement. You’re always fully aware when you’re playing sport that one of your mates is also trying to take your spot. It’s just the way it is. I never felt that there wasn’t that encouragement, you tried to enjoy each other’s success as well. But they were two fine players, sadly no longer with us.

A professional’s cricket season is arduous. Before the County Championship adopted a two division format in 2000, a County XI would play 22 matches from late April to mid-September. That’s before you add in the Sunday League fixtures, and the two (Benson and Hedges, Natwest) one day competitions. In 1991, for example, Northants finished a game against Glamorgan in Cardiff on May 24. They had to be in Leeds the following day to start a fixture against Yorkshire. They were in Maidstone playing Kent on July 4; on July 5, they were in Leicestershire18.

It’s a tough life as well, it’s not all glamour, and it’s not all good. When you’re a young player as well, especially back then, wages were rubbish! My first full year, first contract at 18, I was on two grand for six months, and I had to pay £960 in rent! You’re not playing for the money! Basically, if you get on and become a capped player, you’ll do fine. But it’s a hard road getting to that point, and a lot of people don’t make it.

In those days, [a season] was 90 days of cricket. That’s a tough old season! And the travelling, we used to drive ourselves, there was no buses in those days, no team bus, not ‘til the last year of my career!

Interviewed by the West Briton in 1995, Tony stated he drove on average 10,000 miles every summer, plus all the cricket19.

One conjures up an image of the country’s motorways clogged during the summer months with the vehicles of numerous professional cricketers, crammed with hungover and/or injured passengers and unwashed kit, flooring it to a venue several hundred miles away. Once there, they’re expected to perform to the best of their abilities, all over again. The glory days, however, make it all seem worthwhile.

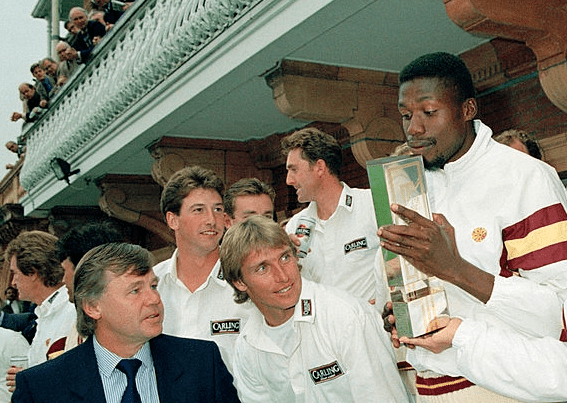

A Cornishman at Lord’s

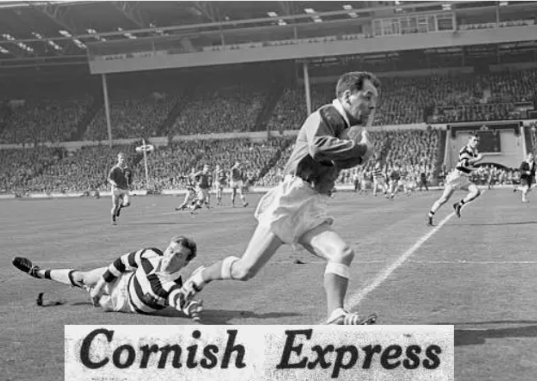

Northants beat Leicestershire at Lord’s to win the 1992 Natwest Trophy. Tony was in the XI, and was treated to an article in a Northampton ‘paper:

Generally described as a dull, one-sided affair (Leicester crawled to 208 off 60 overs; Northants took most of 50 overs to pass the total for the loss of two wickets), playing a Lord’s Final is always special20:

It was wonderful! We bowled really well, we fielded really well. We suffocated Leicester, really. We lost an early wicket, but then Alan Fordham and Rob Bailey had a really good partnership and then all the nerves settled. You just felt that the longer the day went on and the more the sun got on the wicket, it would have been ours to lose, and it turned out that way. We won comfortably.

It’s a great feeling to play in a Lord’s Final, I was very lucky to play in three. But to win one is just a super experience. It really is.

You can play at Lord’s when there’s hardly anyone there and there’s an atmosphere, when it’s 30,000 full it’s just amazing. Empty or full, any day of the week! Derby on the other hand was just a soulless ground. Taunton’s a lovely ground to play cricket, very close. Supporters are very close to you, always a good atmosphere.

1992 was a good year for Tony. He was the Second Team’s player of the year, winning a cheque for £25021.

1992 was a busy year for me. I was in and out of the First Team, when I wasn’t playing First Team I was playing Second Team…and I think in August I played something like 28 days out of 31, or something stupid! It was crazy, when you’re living on your own, you’re a bunch of lads and you’ve got to do your own washing, it wasn’t much fun!

But yeah, I played really good cricket that year, I think winning the Second Team player of the year was mainly down to the fact that I’d played a lot of First Team cricket.

Tony was committed, and he was loyal. The only time he seriously considered a move from Northants was in 1998, when Kevin Curran was captain. Curran only wanted one all-rounder in the XI (himself), and Gloucestershire were making approaches, but…

…I’d had a good year, forced my way into the First Team. And the club had got wind of Gloucester, so they wanted to keep me and offered a three year contract.

So I had a little bit of bargaining power, and I was getting near a benefit as well. So…I stayed at Northants, and they looked after me financially. I’ve got no regrets on that, as nice as it would have been to be closer to home, I was pretty settled in Northampton at that point. I feel quite proud of the fact that I only played for one club.

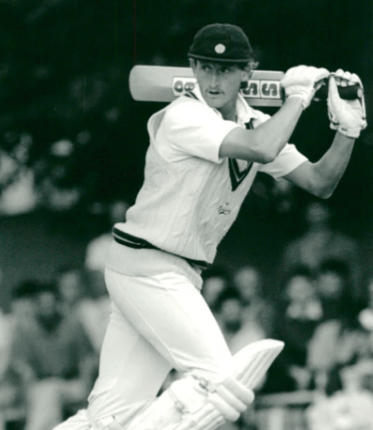

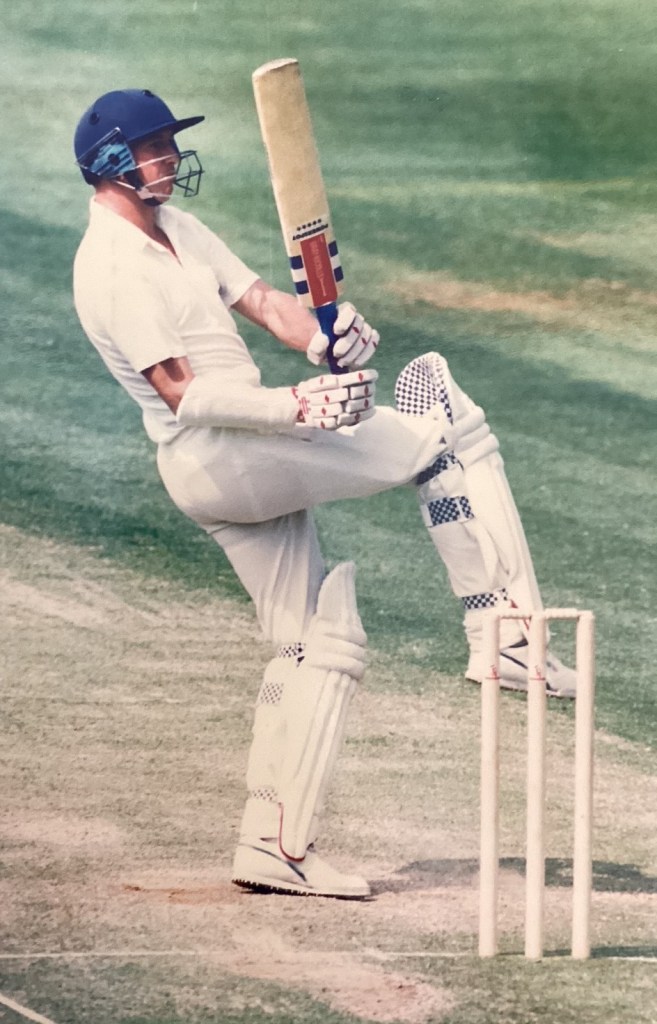

Tony stuck with Northants, and learnt to cope with Wasim Akram reverse-swinging the ball at 90mph on Old Trafford’s super-fast track, or to grudgingly accept that Graham Gooch (upright stance, massive bat, hunger for runs) was usually going to score a ton. In 1994 he was awarded his County Cap after a match at Taunton:

We were chasing 300-odd and were about 150-5! Me and Curtly put on a partnership, and I ended up on 80 not out, I think we won by about two or three wickets. And I got my cap that day.

That was really important for me, you know, your money goes up as soon as you’re a capped player! So that was a big thing. But also I think it was the realisation of my efforts over those years had not gone unnoticed and finally, you feel like you’ve served your time. That was a really important day.

Other important days were around the corner. Tony played in two more Lord’s one day Finals, against Warwickshire in 1995 (Natwest), and Lancashire in 1996 (Benson & Hedges). In the first, two catches were dropped off his bowling (including a chance from his old friend Roger Twose, who went on to make 68), Trevor Penney ran him out for five, and Dermot Reeve survived a plumb-LBW shout to make a match-turning innings. ‘We were stuffed’, Tony said22.

Prior to the 1996 Final, Tony had form against Lancashire, putting on 112 for the eighth wicket with John Emburey in 1995 to steal a one day cup-tie against the Lancastrians. A year later, he was optimistic ahead of the Lord’s showdown, and said so in the Press:

We believe we are a good side when the pressure is on whereas Lancashire, we feel, are inclined to panic a little…

The Independent, July 12 199622

Chasing 245, Lancashire’s Ian Austin picked up four wickets and Northants were dismissed for 21423.

Northants #1 all-rounder

By 1999 Tony had a new contract and was fully committed to Northants. Two other things happened to make this year the most successful of his career. The first was a change in how cricketers prepared themselves for a long season:

One of the best things that happened in the latter part of my career was that cricket became more professional, there was more money in it, and we started having training programmes. I learnt a lot more about myself and the fitness side of things.

I would work on my overall fitness during the winter months. I didn’t pick up a cricket bat from the end of the season until January. I had a month off at the end of the season, and then November to January would be spent in the gym or running, six days a week. Then after Christmas we would up the training but also bring in the skills in the indoor school. It worked for me, it doesn’t work for everyone!

Fitness for a cricketer no longer meant bowling off a few paces in the nets followed by some gentle catching practice. A beer in the changing room after play was replaced by an ice bath (which, I have to say, was an innovation Tony doesn’t look favourably on).

I was probably late 20s, then all of a sudden you’re finding that you’re growing, you’re getting stronger and you’re getting quicker even as you’re getting older, because of the education you’re receiving from the trainers around you.

Look, being an all-rounder is a tough job. There’s no respite from it. So if that’s a career that you want, you have to be fit enough to do it. I always felt that was the one thing I could really control, you can’t control what decisions happen on the pitch, sometimes your form dips or whatever. But if you know that you’ve taken care of the fitness side of it, and you need to make sure you’re fit enough to get through a season…

From when I finished [2003], to where cricket is now, it’s a totally different game. You see the guys playing one day cricket in the field, they’re top quality athletes, they really are!

All his cricketing life, Tony had worked hard and driven himself to get where he was. His new-found focus on overall fitness meant he was ready for the next step.

By 1999, David Capel had retired and Kevin Curran was looking to move on. The position of prime all-rounder in the Northants first team was suddenly looking vacant. Tony, with a long apprenticeship and greater conditioning, was ready to step up, and being Tony, he grabbed the opportunity with both hands. No longer a one-day specialist for the reporters, suddenly Tony was a

…pivotal figure… [who was] …revelling in the all-rounder’s position.

Another ‘paper noted he had finally ‘Stepped out of Curran’s shadow’. And then some. He was Northants’ Player of the Year and even captained the side in several matches25.

I thought it got the best out of me, having added responsibility…it’s hard work in one day cricket, when you’re trying to bowl and think about the next things, it’s very mentally draining. And towards the end of my career I was vice-captain at the club and obviously stepped in to the role as and when needed. If [the captaincy] came to me, great, I had a lot on my plate anyway, and when I did it I was very proud to do it, but I wasn’t shouting for it!

Tony was now a top five batsman, a front-line seamer and vice-captain with Northants. In 2002, he was awarded a benefit season, a largely tax-exempt financial bonus that long serving and successful professionals traditionally look on as a nest egg toward the latter part of their careers26.

Devastated

Yet by the close of the 2003 season, and completely out of the blue, Tony’s contract wasn’t renewed. The club issued the following statement:

At the end of the day, it was felt the club couldn’t make a commitment to him until he had proved his fitness over a lengthy period in competitive cricket.

Source: Cricinfo, September 4 2003

At the time, Tony himself was quoted as being ‘devastated’27. Even now, it still rankles:

It disappointed me because…the thing is, I’d been very lucky, all my career, with regards to injuries, and in 2001 I played a whole season with a prolapsed disc in my back which was really difficult! I got through the season, and two games before the end of the season I needed an injection in my shoulder as well. So I’d put my body on the line and literally I think it was two or three weeks after the end of the season I had an operation on my back.

I’d never been one to miss a lot of cricket. And then I just had a silly Achilles tendon problem, that occurred the Christmas before the [2003] season started. These things can really take time to heal and it wasn’t ready for the start of the season. I was able to practice but I couldn’t run a lot.

Tony would have skippered a lot of games that season, and Northants were desperate to get him back on the pitch. In the end, though, he spent a lot of time in surgery and only managed one Championship game in 2003. Northants gained promotion to Division One28.

An anti-inflammatory injection into the tendon merely led to another injury, and Tony was back to square one.

I played a lot in the Second Team, just batting and fielding at slip. I couldn’t bowl. Running between the wickets was a real problem, but I was keeping my eye in, you know? I was getting runs, and feeling confident, so if I did get fit, and got back in the First Team, I was ready.

…then I niggled it again in my recovery, but I got back in August. I played in the Second Team, bowled 20 overs in the day, I was back in the squad for the Sunday League…

Playing a gentle game of soccer in a Second Team warm up, Tony felt like he’d been ‘shot in the leg’: the muscle had ruptured again.

That was the end of my season – but my contract was up.

Northants had also been taken to the cleaners by one of their accountants to the tune of £80K29.

And the club…decided…not to give me another contract. But I’d been told, with rest over the winter, that I would make a full recovery.

Another player who had had an injury-hit season had been given until April 2004 to prove his fitness, but not Tony.

I said to the club, look, the reason I’ve been having these injuries is because I’ve been trying to get back on the pitch, and feeling like I’ve been pressurised to get back on the pitch. I’ve done everything I can to get back…I asked them if they’d spoken to the club doctor, and they said no!

So I said, you’re basically concerned about my fitness, but you haven’t spoken to the club doctor. That’s rubbish! After twenty years’ association with this Club, and everything I’ve done, be honest with me.

I just thought it was really poor. You always know the day’s going to come, when you’ve got to make the decision, or the decision’s made for you, but if you’re going to do it, do it the right way.

Time’s a great healer, but it wasn’t good, the way it was done.

Troon Boy

Tony’s benefit had happened at the right time. He now runs the UK office of a German owned joinery company in Northampton.

It seems, though, you can take the boy out of Cornwall, but you can’t take Cornwall out of the boy. Tony played Minor Counties cricket for Cornwall until 2006, thus proving to a certain extent that he still had gas in the tank. He also keeps an eye on Troon, his old club, who after withdrawing from all forms of cricket in 2021, reformed a year later. This year, 2025, Troon CC celebrates its 150th birthday30.

It was really sad [when they folded], really sad. When you look at iconic clubs in Cornish cricket, Troon is right up there. So to see something that has been quite a big part of my life, not only the club but the clubhouse, that used to be separate to the club, I spent hours down there as a kid! To see all that go, and the club struggle and not play for a season, was really sad.

You just hope that the club keeps going. 150 years is a fantastic achievement. You hope that the cricketers of today and those running the club will keep going and keep being an inspiration to the younger kids in the village, and giving them the opportunities that we had, when we were young.

I’m forever grateful for the cricket club, and the village, for what they gave me.

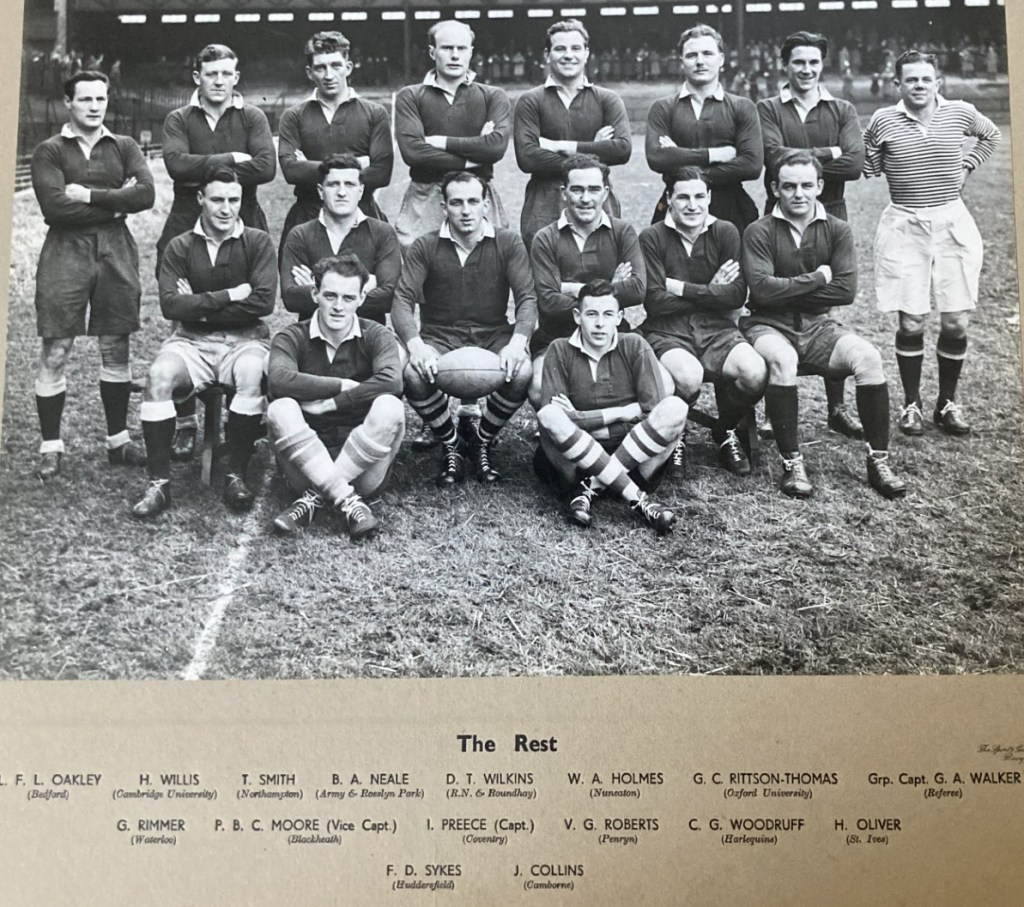

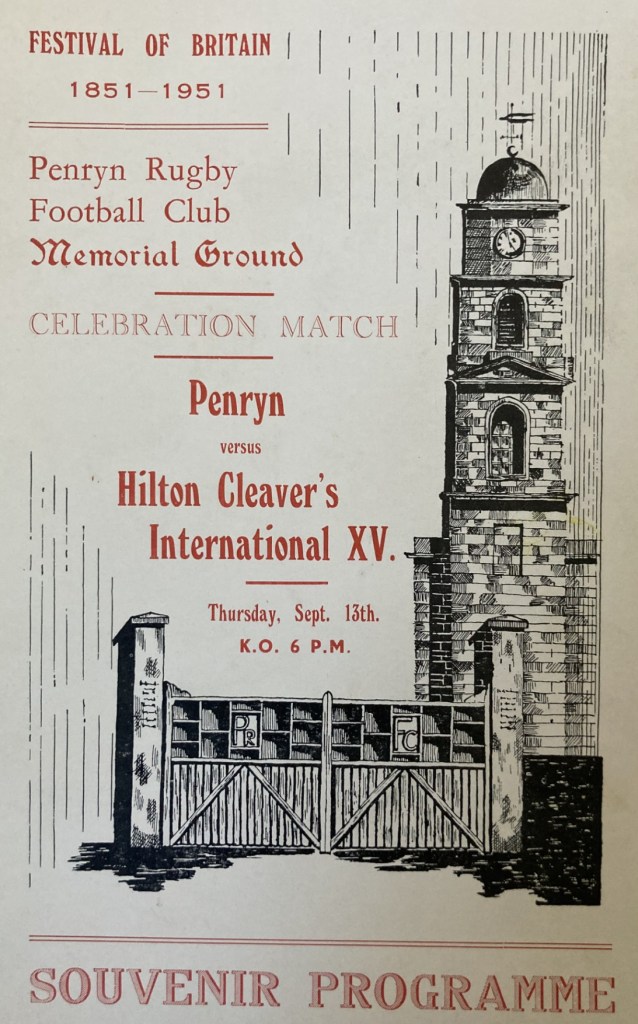

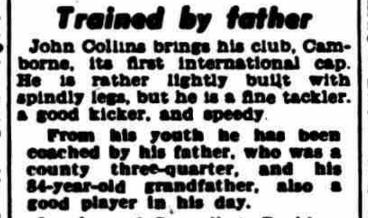

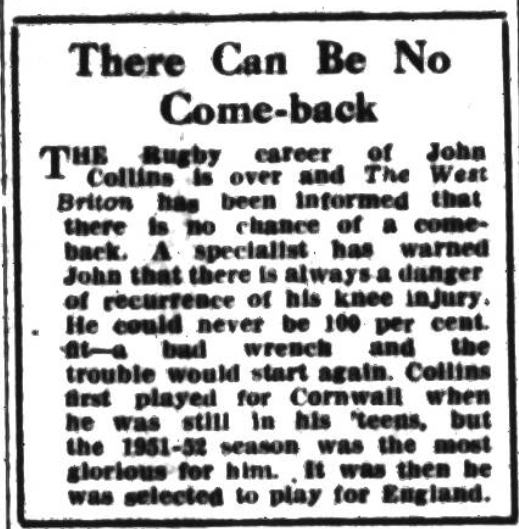

My previous Cornish sporting hero was John Collins, the Camborne, Cornwall and England Rugby player. Find out all about him here.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Image from: https://www.nationalvillagecup.com/classic-match-troon-versus-astwood-bank-national-village-cup-final-1972/

- Such a long spell would never be allowed now for a youngster. Prior to the formation of the Cornwall Premier League in 2001, all innings in the Cornish cricket leagues consisted of 48 overs per side. Thus for many years the maximum number of overs a player could bowl was 24 – regardless of your age. I personally remember toiling through a 17-over spell at the tender age of 14 in a senior match. This maximum number of overs for a bowler was reduced to 16 at the same time (find reference?), and gone were the days when two spinners would bowl unchanged through an innings. As of 2022, the maximum number of overs a bowler can bowl is ten. To reduce injury to young players, nowadays a player of Tony’s age can only bowl five overs in a spell with a maximum of ten in a day. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cornwall_Cricket_League, https://resources.ecb.co.uk/ecb/document/2020/03/16/bf713bed-4a76-4218-9ef0-f4edb8ed2c2d/2020-Fast-Bowling-Directives.pdf, https://www.facebook.com/cornwallcricketleague/posts/overs-per-bowler-clarification-div-2-3-is-now-a-max-of-9-following-the-close-sea/406689847959573/

- West Briton, January 20 1983, p35.

- See: https://schoolsportmag.co.uk/state-school-cricket-in-crisis-or-at-crossroads-apr-2024/

- West Briton, August 4 1983, p40.

- West Briton, June 12 1986, p24; May 7 1987, p23.

- These were players of the highest calibre. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Taylor_(cricketer), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geoff_Marsh, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dean_Jones_(cricketer)

- Naturally, Tony’s feats made the West Briton: June 22 1989, p23.

- Northampton Chronicle, April 25 1992, p36.

- Images from: https://imsvintagephotos.com/products/david-capel-vintage-photograph-931689?, and https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2012/oct/10/kevin-curran-zimbabwe-bowler-coach-dies

- Northampton Evening Telegraph, July 7 1992, p27.

- Images from: https://cricketlife.co.uk/player-profiles/winston-davis/, https://www.reddit.com/r/Cricket/comments/1bf8knb/chin_music_michael_atherton_athletically_avoids_a/, https://www.sporting-heroes.net/cricket/west-indies/patrick-patterson-2248/test-record_a01861/

- Greg Thomas’ career was wrecked by two things: injury, and always being picked to play the West Indies. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Greg_Thomas

- Image from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/uk/348740.stm. For more on this story, see: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/lamb-goes-on-front-foot-over-balltampering-lawyer-attacks-cricket-administrators-after-libel-case-ends-amid-claims-of-coverup-1505593.html, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/botham-and-lamb-bowled-over-by-defeat-in-pounds-500-000-high-court-test-1307606.html

- For more on Procter, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mike_Procter

- See: https://www.espncricinfo.com/cricketers/eldine-baptiste-51211, and https://nccc.co.uk/first-team-history-1905-2019/. For more on Roberts, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Roberts_(cricketer,_born_1976)

- For more on Twose, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roger_Twose

- See: https://static.espncricinfo.com/db/ARCHIVE/1991/ENG_LOCAL/CC/

- February 7 1995, p49.

- See: https://www.espncricinfo.com/series/national-westminster-bank-trophy-1992-418852/leicestershire-vs-northamptonshire-final-418885/full-scorecard, and Northampton Chronicle, September 7 1992, p26.

- Northamptonshire Evening Telegraph, September 26 1992, p27.

- See: https://www.espncricinfo.com/series/national-westminster-bank-trophy-1995-418986/northamptonshire-vs-warwickshire-final-419021/full-scorecard

- Available at: https://www.the-independent.com/sport/penberthy-reveals-grounds-for-optimism-1328526.html

- See: https://www.espncricinfo.com/series/benson-hedges-cup-1996-491646/lancashire-vs-northamptonshire-final-491703/full-scorecard

- The quotes and information can be found in: Northampton Chronicle, June 12 1999, p44; Northamptonshire Evening Telegraph, July 22 1999, 74; September 20 1999, p20.

- See: Northamptonshire Evening Telegraph, June 14 2001, p78. For more the benefit system, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benefit_season

- Northampton Chronicle, September 4 2003, p40.

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Northamptonshire_County_Cricket_Club_seasons, https://www.espncricinfo.com/story/northants-release-penberthy-133430

- Source: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/northamptonshire/4026837.stm

- See: https://www.falmouthpacket.co.uk/news/19261589.troon-cricket-club-withdraws-cornwall-cricket-league/