(With the invaluable collaboration of Nick Serpell, club historian, Redruth RFC.)

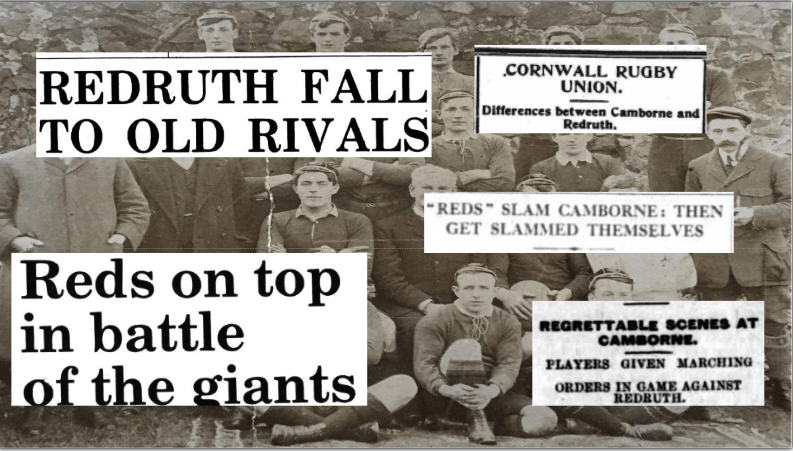

Reading time: 25 minutes

You that follow foot-bal playing…you are to be condemned from God…it must be laid down in the dust.

~ George Fox (1624-1691), The Vials of the Wrath of God, London, 1655, p11

We wish each other the compliments of the season then get stuck in…

~ W. A. “Billy” Phillips, Redruth RFC, 1952; courtesy Nick Serpell

Rugby anarchy…

In 1958 Warwickshire beat Cornwall at Coventry to win the RFU County Championship. They should have been jubilant, but far from it. The winning XV’s skipper complained bitterly about the 5,000 Cornish fans’ allegedly endless barracking, and Cornwall’s play was noted as being

…frankly disgusting…

Daily Mirror, March 10 1958, p23

Boots and fists were swung with gay abandon. So tough were the Cornishmen that one of their XV played most of the game with a broken jaw; Camborne man Terry Symons, who watched the game, states that Warwickshire were no milksops either.

Cornish rugby was clearly somewhat different, and rather more robust, than the upcountry version.

Quite simply, it’s the way Cornish rugby was – and often still is – played. The opponents are treated as deadly enemies because, all too regularly, that’s just what they are. Historians have realised that, in

…Devon and Cornwall, the game resembled soccer or rugby league in being a vehicle for fierce community rivalry.

Tony Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, Routledge, 2009, p110

Although there was no official league structure until the 1987-88 season, it didn’t take the prospect of promotion, relegation or a title to add spice to a fixture1. Cornish clubs played each other as often as they liked, and the gentlemanly notion of playing for sheer recreation2, was rapidly forgotten as working men from one town or village competed with other working men from a nearby town or village for, well, bragging rights.

The first twenty minutes of any local derby, a former player told me,

…was war…

Sometimes, twenty minutes wasn’t quite long enough.

From the 1870s, when Cornwall’s first rugby clubs were formed, and the outbreak of World War Two, rugby existed in a state of nigh-on lawless anarchy. Formed in 1883, the CRFU tried (often in vain) to bring some semblance of structure to the game.

Consider page six of the Cornishman from February 12, 1903. There is a report of a CRFU meeting. The items on the agenda were as follows:

- Falmouth wanted Illogan RFC fined for non-attendance of a fixture;

- Falmouth also claimed expenses from Penryn for not fulfilling another fixture;

- The “occurrence” at St Ives was debated: in a match versus Penzance a player from the latter XV struck an opponent, which led to a brawl between players and spectators both;

- Another discussion centred around a game between Penzance and Falmouth: after the match, two Penzance players had allegedly climbed aboard their opponents’ team bus and carried out a “brutal assault” on a Falmouth player.

(Remember, that’s just one newspaper, from one week.)

By 1921, an exasperated CRFU believed that “extreme town rivalry” was leading to the decay of Cornish rugby:

…it would be a good thing if the English Rugby Union came down and closed all the grounds in the county…a disgrace…too much antagonistic spirit…

Cornubian and Redruth Times, December 1 1921, p6

But nothing happened. In 1929 a member of Newlyn RFC’s committee stormed onto the pitch and put his knuckles through the jaw of a Penzance player. Further fixtures between the two clubs were postponed, and the committee man suspended, which is perhaps the sole reason why Newlyn didn’t pick him for their next match3.

In 1931, Troon’s match with their neighbours from the other side of Black Rock, Porkellis, was abandoned with twenty minutes to play:

…the game was one continuous fight, in which spectators also had a part.

Cornishman, March 19 1931, p6

(It’s unclear whether the game was abandoned, and the fighting continued.)

Rivalries were so intense between clubs they couldn’t even bear to play one another: Penzance wouldn’t play Newlyn. Falmouth wouldn’t play St Ives. Redruth wouldn’t play Penryn4. And so on.

So, what’s the greatest Cornish rugby rivalry? Before they combined in 1944, the animosity between Penzance and Newlyn was legendary. Others will stake a claim for St Ives and Hayle. Some will plump for Falmouth and Penryn.

Maybe that’s a question that cannot be answered.

But there is one rivalry that, apparently, is played out every year, without fail, on Boxing Day.

Is it the oldest?

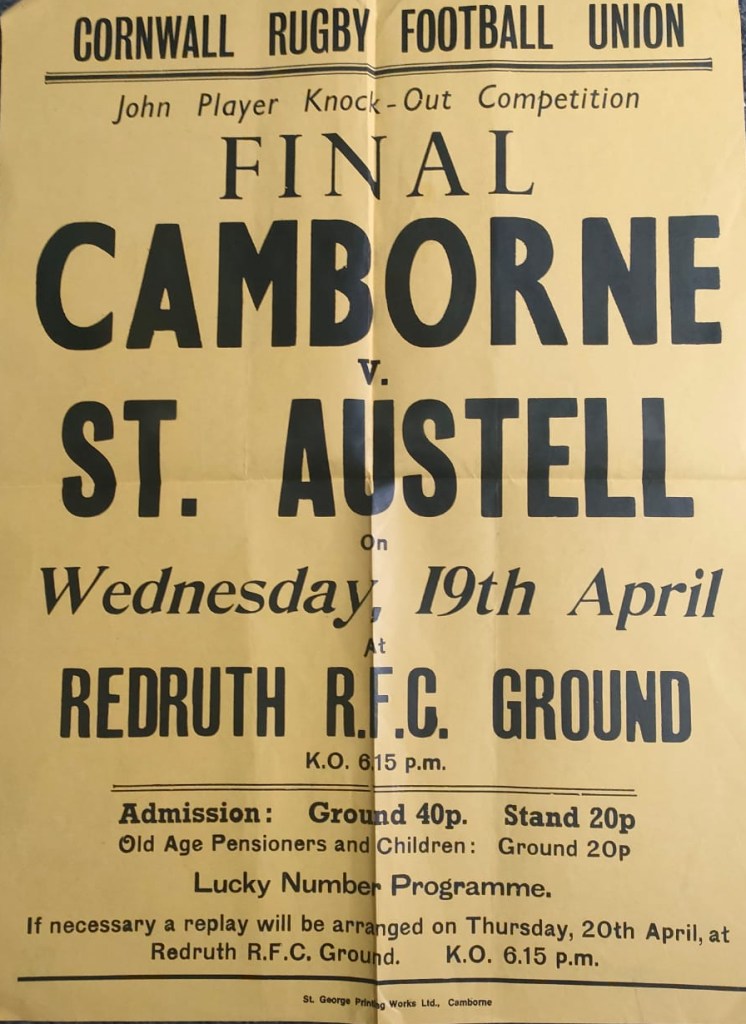

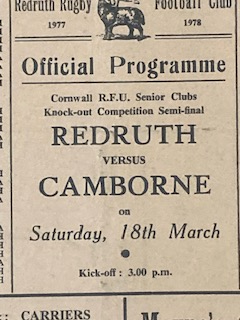

It is claimed that the festive fixture between Camborne and Redruth RFC has been honoured for so long – since 1877 – that it now holds the title of the oldest continual rugby fixture in the world5.

It’s one of the few things both clubs agree on:

…a rivalry which has lasted 134 years, making the game the world’s longest continuous rugby fixture.

Redruth RFC Boxing Day preview, 20186

One of the oldest continuous Club fixtures in World rugby…

Camborne RFC Boxing Day preview, 20197

Similar assertions are made on both clubs’ Wikipedia entries8. Let’s answer the question right now:

The Boxing Day game between Camborne and Redruth is not the oldest continual rugby fixture in the world.

That other XVs assert that their fixture is in fact older, is actually irrelevant9. The now-annual Boxing Day derby between Camborne and Redruth cannot be the oldest continual fixture, because Camborne and Redruth haven’t met every Boxing Day since 1877, even when we allow for the obvious qualifications, such as two world wars.

In fact, not counting the years 1939-45 (and even wartime exceptions are far from clear-cut), or the 1998 edition that was abandoned on account of a waterlogged pitch (yet was replayed in May 1999)10, Camborne and Redruth have played every consecutive Boxing Day since…1928.

That’s 89 matches, over 94 years from 1928 to 2022. That’s still impressive.

But it’s not the oldest.

A false belief has developed over time that

Originally the Boxing Day fixture was always played at Redruth and the main Camborne home fixture against Redruth played on Feast Monday.

West Briton, July 9 1992, p20

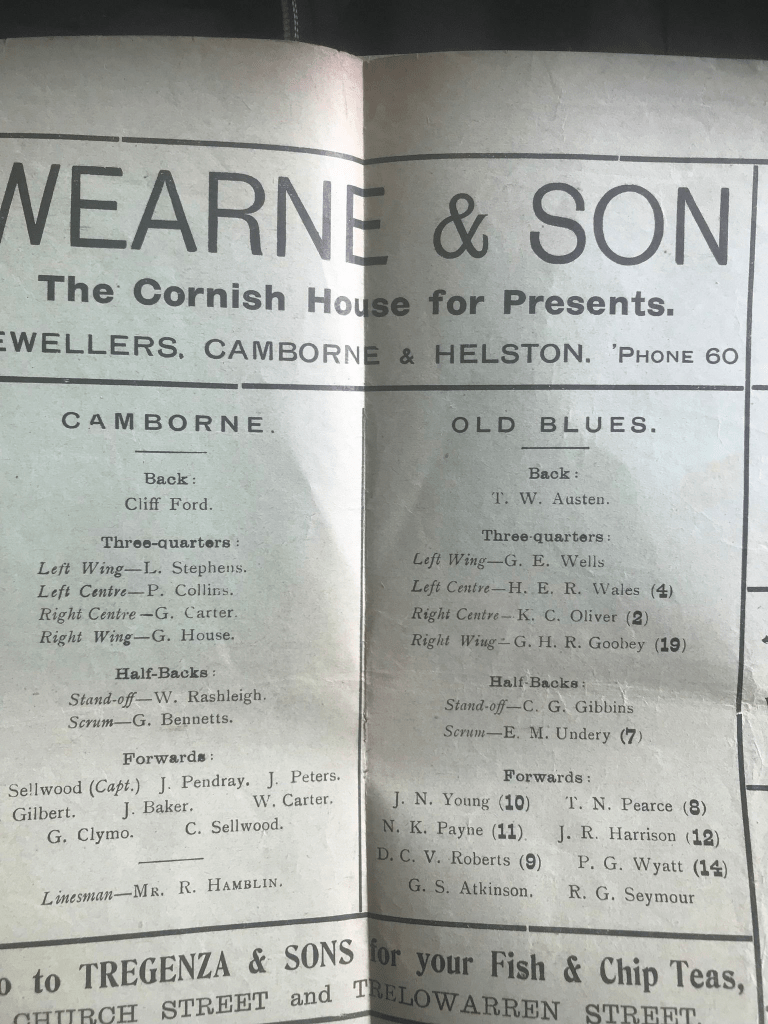

As we saw last week11, Camborne didn’t in fact play Redruth on Feast Monday until 1900, and enjoyed annual ‘Feast’ fixtures with Surrey’s Old Blues RFC from 1921-1934. The Camborne-Redruth Feast Monday fixture only became a nailed-on certainty from 1945 until its demise in 1963.

The disbandment of the Feast match left the Boxing Day derby with no real competition in the season’s calendar, and it quickly gained precedence.

Feast Monday rugby was forgotten, and Camborne’s John Collins (one of the few men still around to have played in both derbies) readily admits that, in truth, Boxing Day was always the one, for both XVs.

Here we come to the crux of the matter. The importance of the Boxing Day game, indirectly cemented by the loss of the Feast clash, is so great for both clubs nowadays, people believe this to have always been the case. It’s a short leap from thinking this to convincing yourself that Camborne and Redruth have always, therefore, played on Boxing Day.

Without getting too technical, this is what historians call an invented tradition:

…a set of practices…of a ritual or symbolic nature…which automatically implies continuity with the past.

Eric Hobsbawm, “Introduction”, in: The Invention of Tradition, ed. E. Hobsbawm and T. Ranger, Cambridge University Press, 2012, p1

A set of practices – a game of rugby on Boxing Day – has, over time, come to represent or symbolise the immutable historic rivalry between Camborne and Redruth.

And what rivalry…

No great love lost…

The towns of Redruth and Camborne have historically treated each other with one-upmanship, suspicion, jealousy and, yes, contempt. It’s permeated every aspect of life, especially before the controversial amalgamation of Camborne and Redruth in the 1930s, and the further formation of Kerrier District Council in 197414. After this, the rivalry generally expressed itself in the sporting sphere15.

To give but one example. In 1892 it was felt that Redruth ought to have a fire brigade. Apart from the obvious reasons posited why this should be so, it was also stated that

…there is no getting over the fact that Camborne possesses a fire brigade…while Redruth has none of any sort.

Cornish Post and Mining News, November 19 1892, p4

Redruth got its fire brigade, to the obvious chagrin of Camborne’s. By 1906 competition was such that one brigade would not allow the other to assist in fighting a fire on its own turf, with tragic consequences. The verdict was that

…there was no word bad enough to condemn the rivalry which existed in connection with the brigades of the two towns.

Cornish Telegraph, April 5 1906, p616

I could go on all day with this kind of thing, but I cite the issue of the two fire brigades because it illustrates the towns’ rivalry blurring between the civic and the recreational. Camborne’s fire chief, Josiah Rowe, also played rugby for the town. Redruth’s chief, W. E. Tamblyn, played rugby too, for Redruth17.

The lawyer C. V. Thomas, in debating the pros and cons of a proposed Camborne-Redruth tramway, observed that

…there appeared to be no great love lost between the two towns.

Cornishman, November 17 1898, p6

Thomas had brought rugby to Camborne from his public school18, and would have therefore known that the rivalry was present in all socio-cultural aspects of the towns’ relationship.

In fact, Redruth and Camborne had been competing at sports for centuries before the advent of rugby football. The Camborne Parish Registers of 1705 note that William Trevarthen was

…disstroid to a hurling with Redruth men at the high dounes the 10 day of August…

The ‘high downs’ were probably Carn Brea. I am grateful to Nick Serpell for showing me this19.

In the late 1800s though, hurling (an ancient inter-parish game involving two opposing mobs, a ball, and few if any rules), was old hat. By 1875, Redruth had a rugby team…so why not Camborne?

Nick Serpell, whose forthcoming book to mark the 150th anniversary of Redruth RFC promises to be a blockbuster (and I’m a Camborne man that says it), has searched in vain for the source of the following quote which purportedly appeared in a local ‘paper in 1877 and prompted the formation of Camborne RFC:

…after all, Redruth have got one.

qtd. in Tom Salmon, The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall, CRFU, 1983, p41

I can’t find it either. The quote may be apocryphal, but the sentiment in Camborne obviously wasn’t. By November 1877, Camborne RFC had played – and lost – its first match20. By Boxing Day 1877, they had played – and also lost – their inaugural game against Redruth.

1877-1914: I would half kill you…

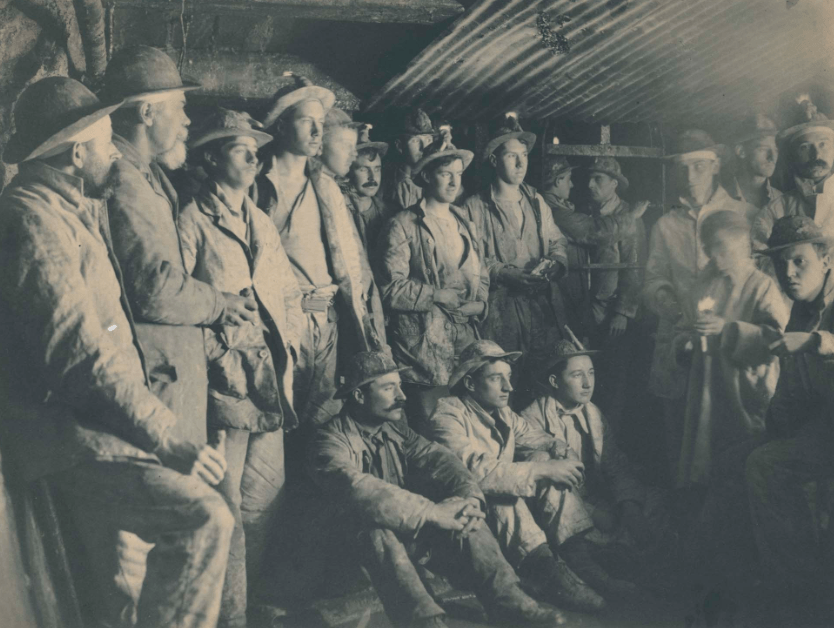

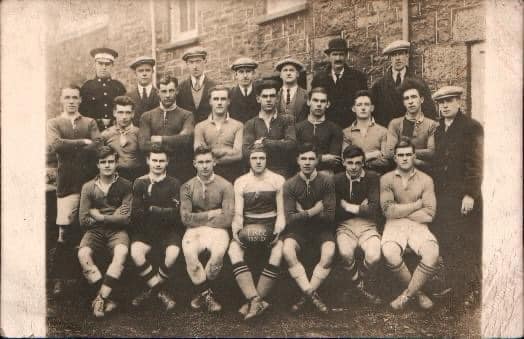

As Nick Serpell has pointed out, the inaugural Camborne-Redruth match wasn’t even played by their first XVs. The report of the match notes it was the clubs’ “juvenile” teams that took the field: at this embryonic stage of its existence, Camborne had fifty players on its roster, and Redruth could presumably boast a similar number.

On Boxing Day 1877, Camborne’s Chiefs were at Penzance; Redruth’s were away to Bodmin. The very first Camborne-Redruth Boxing Day match was battled out by the Reserve XVs21.

Traditions don’t come ready-made; they evolve over time. So do fixture lists. Hence, Camborne and Redruth didn’t meet again on Boxing Day until 1885, and then again not until 1890, when Redruth’s grandstand collapsed, injuring several unfortunate spectators. There was then another gap up to 1900, from which there was an unbroken sequence of Boxing Day matches up to 1910, when Camborne finally overcame a Bert Solomon-inspired Redruth and recorded their first Boxing Day victory22.

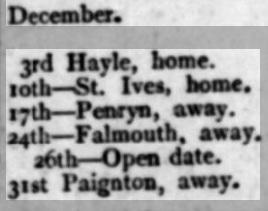

Before 1900, Redruth enjoyed festive matches with Bodmin, St Ives or Liskeard, and Camborne even travelled to Plymouth Athletic in 1883.

In the fifty years between 1877 and 1927, Camborne and Redruth only met on Boxing Day on 20 occasions.

But that doesn’t mean there wasn’t any kind of rivalry; indeed, like most other Cornish clubs in this era, the rivalry threatened the very existence of Cornish rugby itself.

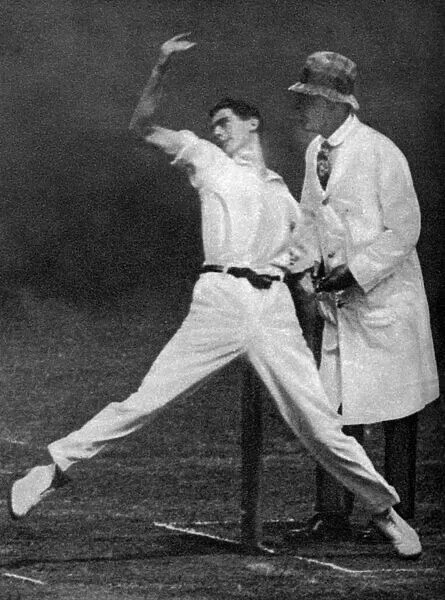

By April 1912 Redruth were Cornish champions for the 1911-12 season (P30 W24 D3 L3), but there was one last game to play, perhaps the most important one: a deciding rubber at home against Camborne. The previous three fixtures had seen one draw and a victory apiece, hence there was a lot to play for. The atmosphere was incendiary.

Before he had even set foot on the pitch, Camborne’s county player, Tom Morrissey, had to endure what we would call racist abuse. Hecklers kept up the taunt that he was a

_______ Irishman…

West Briton, April 22 1912, p3

…throughout the match. Several times, Morrissey bared his arse in protest to the Redruth grandstand. Horrified female spectators walked out in disgust. Redruth’s Rector later spluttered that

…he should not go in the ground again.

West Briton, April 29 1912, p4

(A Redruth committee man later stated that there had been “no more [barracking] than usual” during the game.)23

Morrissey also got into a fight on the field with a Redruth player, Menhennett. Whilst they were going hard at it, another Camborne and Cornwall man, Sam Carter, dragged Menhennett up, teed off, and knocked him cold with a haymaker. The referee remonstrated with Carter, who told the match official that

If you had ordered me off I would half kill you…

West Briton, April 22 1912, p3

Oh, Redruth won, 6-0. At the conclusion of the match, two opposing players were still pummelling each other, which seemed to be the cue for several hundred spectators to enjoy a brawl of their own on the pitch.

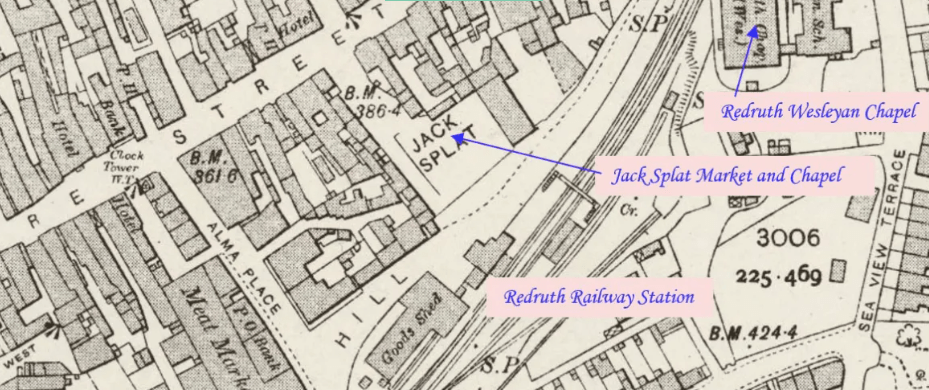

The CRFU convened meetings in Redruth which was already, much to Camborne’s ire, known as the “seat” of Cornish rugby24. The Union deplored the fact that rugby was becoming “a disgrace” in Cornwall25. Redruth’s secretary threatened resignation unless the matter was resolved, and resolved it was.

Menhennett was suspended for one playing month; Carter, a year. Morrissey received a two-year ban. A Camborne committee member condemned the CRFU and Redruth RFC both:

…excuses were made for the conduct of any Redruth man, but when a Camborne man was before them he must be cautioned or suspended…the Redruth ground [should be] suspended…for provocation…

West Briton, April 29 1912, p4

Camborne RFC protested to the RFU, but to no avail. Carter and Morrissey gave the CRFU – and Rugby Union in general – the ultimate two-fingered salute in signing professional contracts with Rochdale Hornets…but that’s a story for another day26.

Camborne and Redruth didn’t meet on a rugby field for the entire 1912-13 season.

When they finally did feel like facing one another again, for the 1913-14 season, the “hatchet was buried”. The two XVs would meet four times a season: Easter Monday in Redruth, Feast Monday in Camborne, Boxing Day and the final Saturday match to be alternated, gates were to be shared, and referees to be appointed from outside Cornwall – no Cornish official could be deemed neutral enough to manage a game between Camborne and Redruth. All was sweetness and light. It’s peace in our time27.

But it wasn’t to be peace, in Camborne, Redruth or Europe. At the outbreak of hostilities, the CRFU vowed to “keep the game going as far as possible”, but by November 1914 all rugby had officially ceased28.

That’s officially. On Boxing Day 1914, Camborne beat Hayle 12-0, with all proceeds going to the war effort. The only reason given as to why Camborne didn’t play Redruth is that attempts to arrange a fixture “failed”. So much for the solemn vows made in 1913. Although such unofficial matches were in a good cause they generated some controversy, as in why aren’t these healthy young men at the Front?29

As conscription got tighter, though, even these fixtures dried up. There were no Boxing Day matches between 1915 and 1918.

Crowds and fans: the good, the bad…

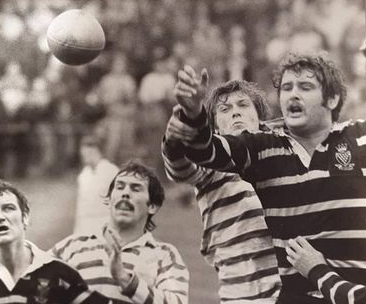

From all the Camborne and Redruth players I’ve spoken to, from the 1950s right up to the present, the impression one gets of the crowds at derbies, and fans of the clubs in general, is one of immense passion that, at times, can overstep the mark.

The Boxing Day game always “generated a great atmosphere”, I was told, and like turkey and presents, it was

…just something that was in everyone’s calendar each Christmas…

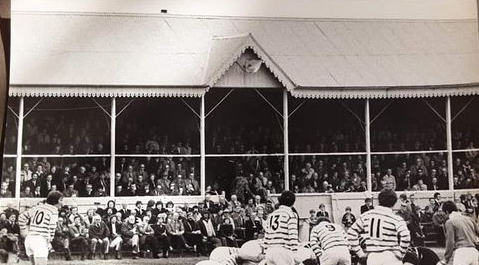

Crowd sizes in the 1970s would rival the gates for Cornwall’s fixtures. A recent Redruth player told me that a home Boxing Day match would draw bigger attendances than most of their National One (or tier 3) games. In 2004, 1,500 came to Redruth to watch Adrian Downing score a last-gasp try for Camborne to scrape a 10-all draw: it was the club’s biggest crowd of the season30.

3,000 turned up in 1988 to see a Jonathan Willis and Tony Cowling-inspired Redruth prevail 19-9 over Camborne31. In the immediate post-war era, with perhaps less distractions, crowds could total 7-8,000. Special Roy of the Rovers-style courtesy buses would transport Camborne’s faithful to the enemy’s lair. Those that couldn’t make the trip would gather in Commercial Square until dusk, waiting for the telegram informing them of the result.

In 1947, they would have been disappointed to hear in dispatches that Camborne had lost 6-3, but could take heart from the performance of a 20 year-old wing, guesting from Truro. His name? Robert Shaw32.

In the years when, I was told, “every working man in a ten-mile radius” was employed by Crofty, Holmans, Maxam or Sweb, discussions at work and home regarding the build-up and aftermath of the Boxing Day match would last for weeks. It would be the same in local schools. When Camborne, led by Tommy Adams, “humiliated” Redruth 40-9 in 1992 (Darren Chapman helped himself to 15 points), lame jokes made the rounds in class ever after33.

Such loyalty and interest is obviously, and fundamentally, good for the game. Indeed, a Camborne man from the 1990s couldn’t be more right when he states that the Boxing Day derby is the one for both towns that

…even non-rugby people want to know the result for…

But it doesn’t take much for workplace banter to spill over into raw animosity, and passionate support for your club to become something more parochial and unpleasant.

A Redruth player from the 2000s said that, even though his club were several tiers above Camborne at the time (and only lost four Boxing Day games from 2000-2022),

…some supporters wouldn’t care less if you had a bad season in the league so long as you won on Boxing Day…

Suffice, his overriding emotion after a Boxing Day victory was simple “relief”: he’d let no-one down. Likewise a Camborne player from the 1970s told me that fans weren’t happy unless

…we put fifty points past the bastards…

The grandstands, “ever vocal” (Tom Morrissey would agree), can get out of hand. One Camborne player invited a barracker to meet him for a further ‘discussion’ after enduring insults from that quarter the entire match. Not even match officials are safe. At the controversial conclusion of the 1994 derby, which Camborne won 16-13, the referee had to be protected from outraged Redruth fans by the Camborne XV, with Tommy Adams actually planting a fist on a couple34. But it can also carry on outside the grounds.

A prominent 1980s player actually had to go ex-directory due to the volume of abusive phone messages he would receive around Christmas and New Year. When I asked for examples, he told me they were all “unprintable”.

Speaking of unprintable, Tom Morrissey sadly isn’t the only man to play a derby and be subject to racist abuse. Camborne won the 2003 edition 40-17, but one of their XV was alleged to have been racially taunted by a section of the crowd. As Redruth’s Secretary said at the time,

There is no place in sport for behaviour of this kind…

Roger Watson, Packet, January 3 2004

The Roaring Twenties…

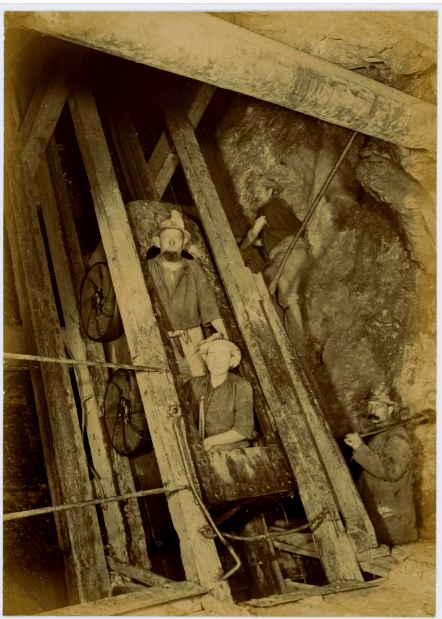

Redruth won the first peacetime Boxing Day match in 1919; a year later it was Camborne’s turn. The 1919-20 season is noted for Camborne returning the best record in Cornish rugby to that date: P37 W31 D1 L535. But it was a false rugby dawn. The Cornish economy was struggling; Dolcoath Mine closed in 1920. At the first Camborne-Redruth match of the 1921-22 season (which Redruth won 6-5), pre-match and half-time singing was provided by The Unemployed Tin Miners’ Choir, and a hat was passed round36.

Men were coming home only to leave again. Representatives of the Northern Union were ever-present with open wallets to prise away the cream of Cornish sporting talent; some rugby players even took jobs in the Arctic Circle37.

In the 1920-21 season, Camborne and Redruth both withdrew from the CRFU’s league competition. They were joined by Penzance in this lack of interest the following season38.

In 1921, Redruth complained to the CRFU regarding Camborne’s playing of a Camborne School of Mines (CSM) student in the recent Feast Monday match. A by-law was cited,

…that men should not be allowed to play for different clubs…

Cornubian and Redruth Times, January 20 1921, p3; Bill Hooper of the CRFU has found no reference of such a by-law existing at the time.

The result of this dispute was that the two clubs didn’t meet on Boxing Day – or Feast Monday – in 1921, 1922, and 1923. Camborne won the 1924 and 1925 editions.

Then, in March 1926, all hell broke loose at Camborne in front of a 2,000 strong crowd. Two Camborne players were sent off for fighting. One Redruth man, likewise. Another Redruth player had his collarbone broken. The referee, a neutral from Devon and probably wondering what he’d done to deserve such carnage, blew no-side with ten minutes still to play. This served to incite a pitch invasion, with Redruth’s skipper being assaulted39.

The clubs didn’t meet again until April 1928. In terms of revenue and prestige, this was a serious split. A Camborne vice-president was banned from all grounds for an entire season for his part in the post-match ruck41. There were calls from within the CRFU to have all Camborne men removed from the board of selectors42. Redruth estimated between 30-40% of a season’s gate money came from matches with Camborne; their total receipts for the 1925-6 season was £729 – £36,600 today. For each season they didn’t play Camborne, 40% of Redruth’s loss would be £291, or £14,640 in 202343.

Money might talk, but it all took some patching up. 7,000 watched Redruth prevail 6-3 at home in the kiss-and-make-up game billed as “the true spirit of rugby”. The crowd – many of whom had been crammed into the ground over ninety minutes before kick-off – were on their best behaviour. There was no foul play or fighting, and the CRFU hosted a post-match celebration at Redruth Market for both teams, where toasts were given, sincere pledges made and many healths drunk44.

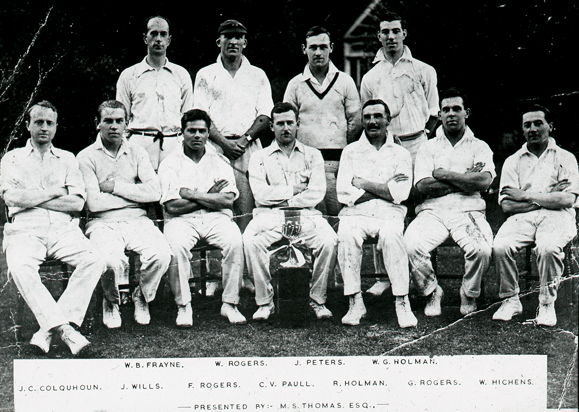

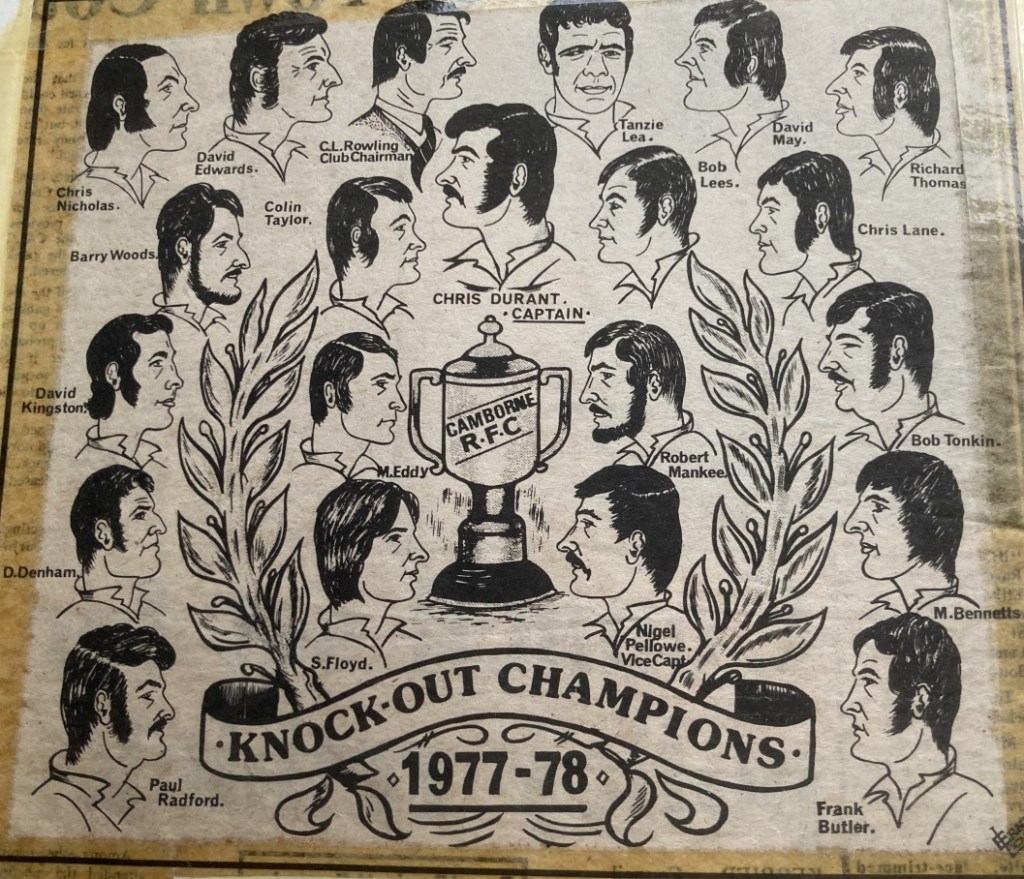

This two-year hiatus raises an interesting point. 1926-7 has gone down in the history of Camborne RFC as one of its greatest seasons, boasting a XV containing such luminaries as Bill Biddick, Fred Rogers, Reg Parnell and Phil Collins. The playing record backs this up: P38 W32 D2 L4; F651, A15145.

But how great a season was it, if you didn’t register a win over or, indeed, play a solitary match against Redruth? Bill Biddick said of this legendary playing year that

No matter where we played, they were all after our blood because we were the tops…

qtd in Tom Salmon, The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall, CRFU, 1983, p43

But you didn’t play Redruth…

To read more of the history of the rivalry up to the present, click HERE…

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

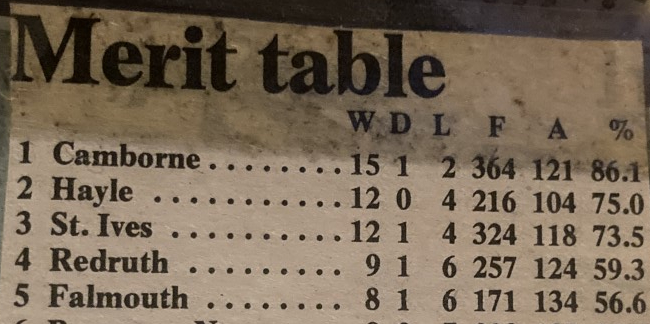

- This statement needs some qualification. By the early 1900s, Cornwall had a league competition, but it was never recognised by the RFU, nor did it involve promotions or relegations. Likewise the CRFU’s Merit Table, which ran from the 1976-7 season until the formation of the National Leagues. The South West Merit Table, which comprised the best clubs in the region, was also never recognised by the RFU. However, a former player described matches in this league as “hard, fast, and physical”. A useful article on the convoluted path to a National League system can be read here: https://therugbymagazine.com/gallagher-premiership/the-birth-of-the-english-champion. See also Tony Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, Routledge, 2009, p110-113.

- For more on the early ethos of rugby union, see my post on the formation of Camborne RFC here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/08/26/cambornes-feast-day-rugby/

- Western Morning News, May 11 1929, p13.

- As noted in the Cornishman, March 19 1931, p6.

- Cornish Telegraph, January 1 1878 p2. Redruth won by two tries to nil.

- From: https://www.redruthrugbyclub.co.uk/news/redruth-v-camborne-or-reds-v-town-or-choppers-v-square-heads-2374590.html

- From: https://www.pitchero.com/clubs/cambornerfc/teams/24388/match-centre/0-4610916

- See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camborne_RFC, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Redruth_R.F.C. Allen Buckley makes the same claim – with reservations – in Bert Solomon: A Rugby Phenomenon, Truran, 2007, p26.

- See here for one example: https://www.heraldscotland.com/default_content/12765683.oldest-rugby-match-celebrates-150-years/

- West Briton, December 31 1998, p45. The May 1999 replay of the 1998 abandonment is included in the list of ‘Boxing Day’ fixtures, as both club obviously felt at the time that the tradition ought to be honoured in some way. It was played in Redruth on May 3, and the home XV won 66-27. West Briton, May 6 1999, p55.

- See my post on Camborne’s Feast Monday rugby here:

- Read John Collins’ memories of his playing days here: https://www.epcrugby.com/2006/12/07/rugby-legend-john-collins-reminisces/

- From: https://www.the-saleroom.com/en-gb/auction-catalogues/truro-auction-centre/catalogue-id-srtru10089/lot-59befb3f-9bb9-40aa-ad78-afb101057fcd

- The amalgamation was initially opposed by an “overwhelming” majority of Camborne and Redruth residents. See: Cornish Guardian, October 19 1933, p12, and the Cornishman, November 30 1933, p2.

- As asserted in the West Briton, July 28 1983, p20.

- This awful tale can be traced in, for example, the West Briton, March 5 1906, p2; Royal Cornwall Gazette, March 8 1906, p3; Cornishman, March 8 1906, p4; and Royal Cornwall Gazette, April 5 1906, p3.

- Tamblyn’s connections to both rugby and firefighting are noted in the Cornubian and Redruth Times, October 18 1895, p2, and May 12 1899, p7. See my post on the formation of Camborne RFC for more information on Josiah Rowe: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/08/26/cambornes-feast-day-rugby/

- For more information on Thomas’ background, see my post on the formation of Camborne RFC here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/08/26/cambornes-feast-day-rugby/

- The fate of William Trevarthen is also noted in Allen Buckley’s Bert Solomon: A Rugby Phenomenon, Truran, 2007, p26. The ancient game of hurling survives in several rural enclaves, and is played annually in St Columb. See footage of the Atherstone ball game in Warwickshire to gain a sense of its violent nature: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1206767323547097

- See my post on the formation of Camborne RFC: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/08/26/cambornes-feast-day-rugby/

- The first Boxing Day derby merits two sentences in the Cornish Telegraph, January 1 1878, p2. Camborne’s impressive squad numbers are noted in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, October 19 1877, p4. That the clubs’ senior XVs weren’t playing each other is listed in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, December 21 1877, p5. With thanks to Nick Serpell.

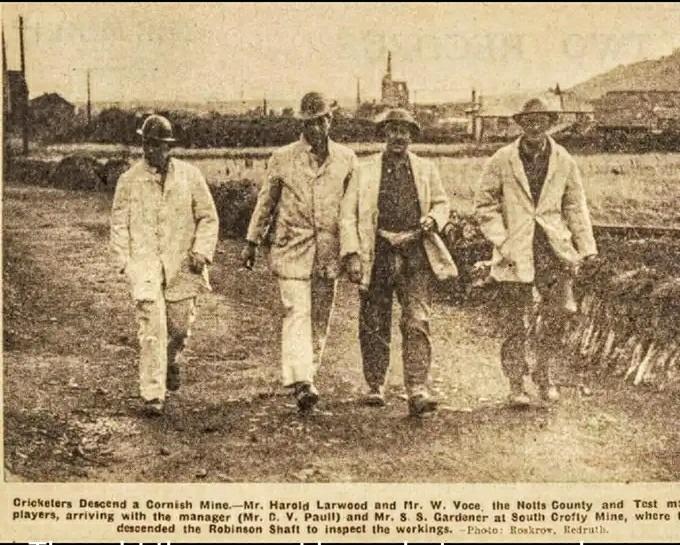

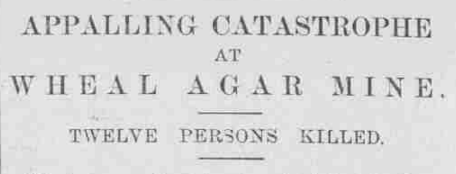

- Nick Serpell has kindly provided me with this early information regarding the two clubs. In the 1911 game, which Redruth won 8-0, their committee had authorised a charity collection for the widow of a Camborne player called William Bassett, who had been recently killed in an explosion at South Crofty. See also: Cornish Echo, December 22 1911, p7.

- West Briton, April 29 1912, p4.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, Redruth Edition, October 27 1898, p9.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, Redruth Edition, October 27 1898, p9.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, April 18 1912, p7; Royal Cornwall Gazette, April 18 1912, p3 and May 23 1912, p5; West Briton, April 22 1912, p3, April 29 1912, p4, September 26 1912, p8. What happened to Sam Carter and Tom Morrissey, along with Camborne’s flirtation with Northern Union rugby, is told here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/02/03/the-great-cornish-rugby-split/

- West Briton, September 11 1913, p6.

- Cornish Telegraph, August 27 1914, p3; West Briton, November 30 1914, p2.

- West Briton, December 28 1914, p3; St Ives Weekly Summary, December 31 1914, p3; West Briton, November 30 1914, p2.

- Packet, January 1 2005.

- West Briton, December 30 1988, p21.

- West Briton, January 1 1948, p2. For more on Shaw’s career, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Shaw_(actor)

- West Briton, December 31 1992, p17.

- West Briton, December 29 1994, p20; For more information on the referee’s experiences, see here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2022/12/26/christmas-rugby-special/

- Cornishman, August 25 1920, p7.

- Cornubian and Redruth Times, October 20 1921, p6.

- Cornishman, July 28 1920, p6; West Briton, October 14 1920, p2.

- West Briton, December 2 1920, p3; Cornishman, October 19 1921, p3.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, March 20 1926, p3; see also the Cornishman, March 17 1926, p5.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, August 28 1927, p8.

- Cornishman, September 15 1926, p6; October 20 1926, p6.

- Cornishman, May 26 1926, p2.

- Cornishman, August 4 1926, p7.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, May 3 1928, p6.

- Tom Salmon, The First Hundred Years: The Story of Rugby Football in Cornwall, CRFU, 1983, p43.