Reading time: 25 minutes

Tackle firmly and strongly; kick hard and safely; field the ball smartly and unhesitatingly…Play the game and do your best!

~ John Jackett offers some youngsters sage advice

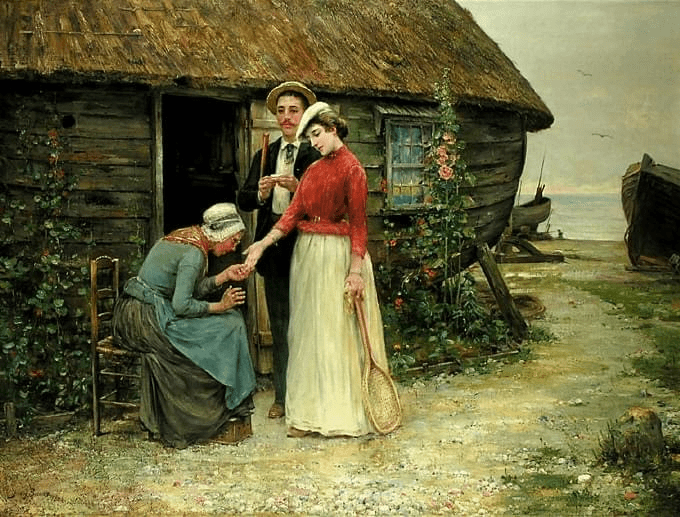

I think I have seen your face and figure represented in a picture?

~ A lawyer at Falmouth County Court narrows his eyes at the young man before him in the dock

Of course John had 1,001 girlfriends…

~ Jackett’s wife, Sallie nee’ Chapman, is under no illusions

Jackett, a modern Bartram…

~ A journalist makes a loaded statement before Jackett’s England debut1

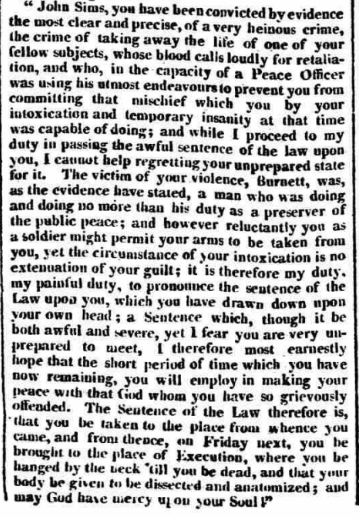

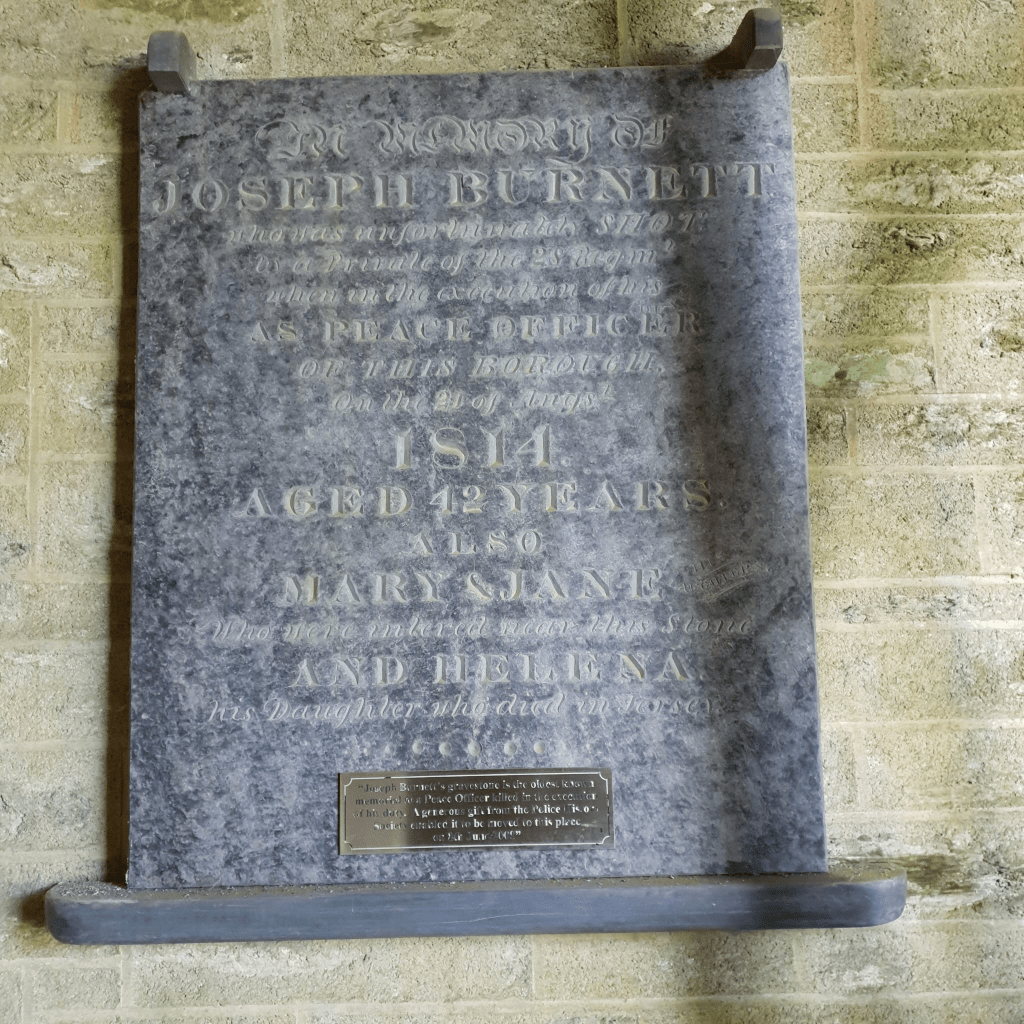

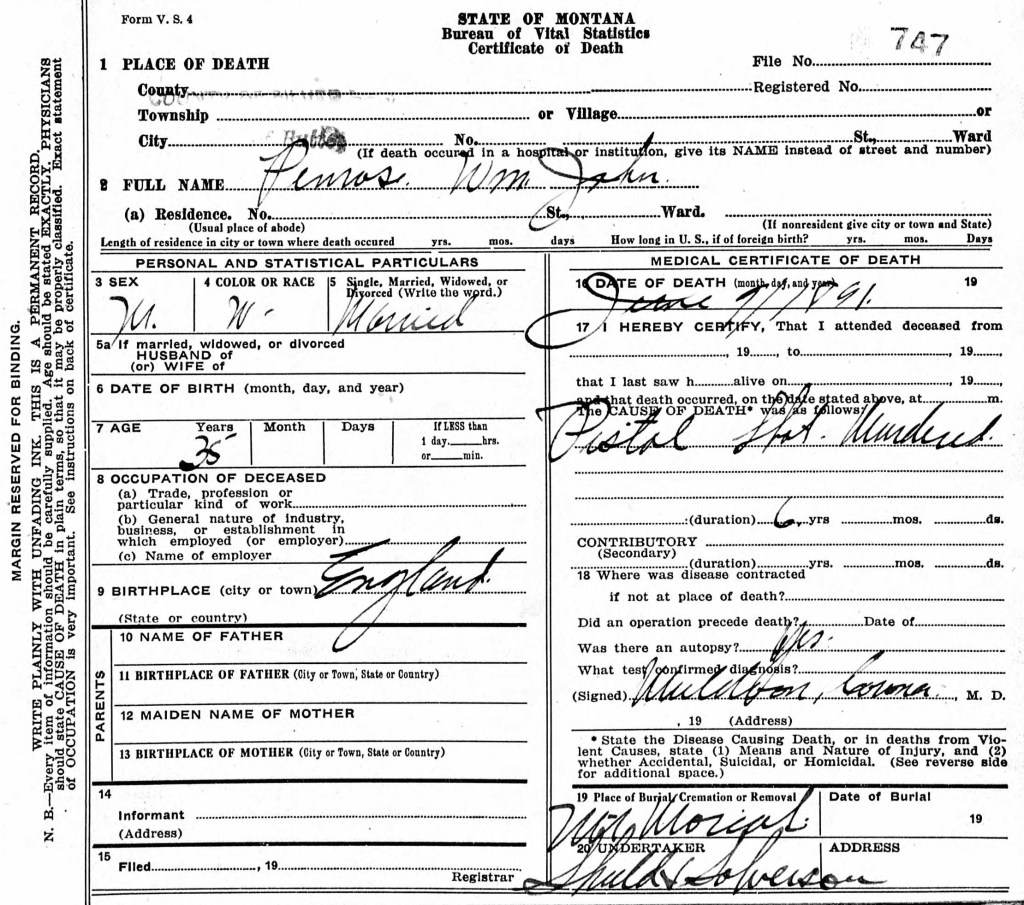

Many figures in Cornish history I choose to write about have a singular occupation, or significant characteristic that piques my interest. Richard Holloway was a lawyer; Beatrice Small a fortune teller; Joseph Burnett a peace officer; Paul Rabey an immoral rogue2.

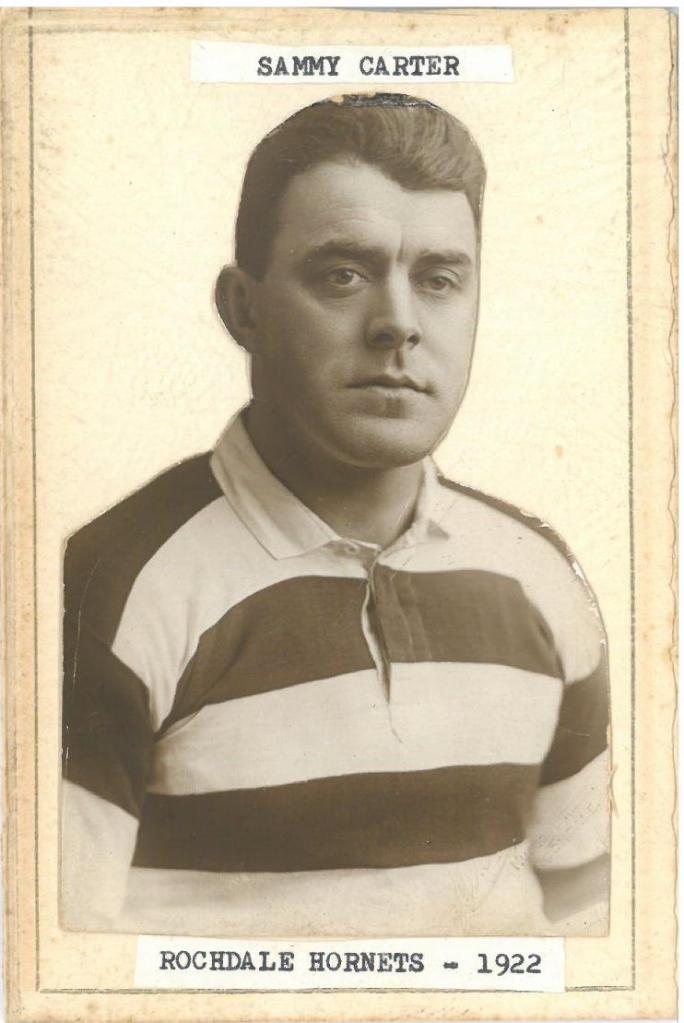

The above-named quartet have one thing in common: nowadays they are all-but forgotten. Edward John Jackett (1878-1935) is different. His achievements and accolades made him renowned in his own lifetime, and celebrated even now. Indeed, the surname ‘Jackett’ is so synonymous with the town of Falmouth that the pathway John and other members of his family took to his father’s prosperous boatyard is memorialised with the following sign:

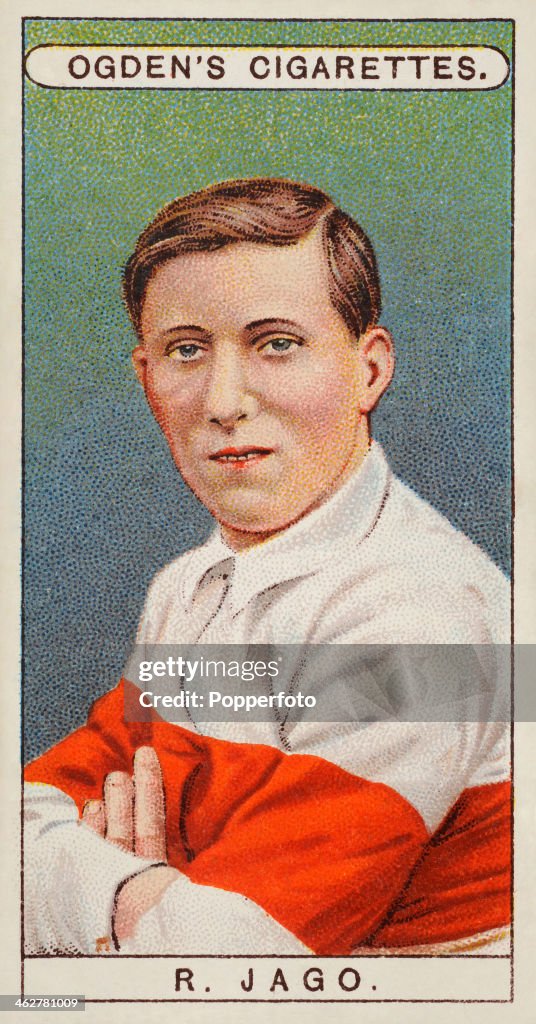

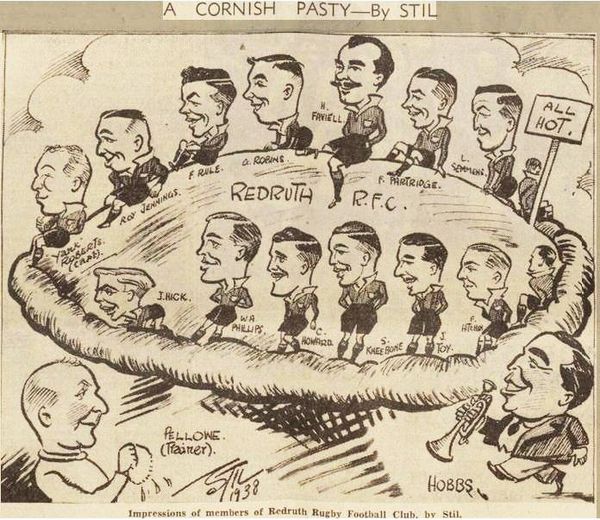

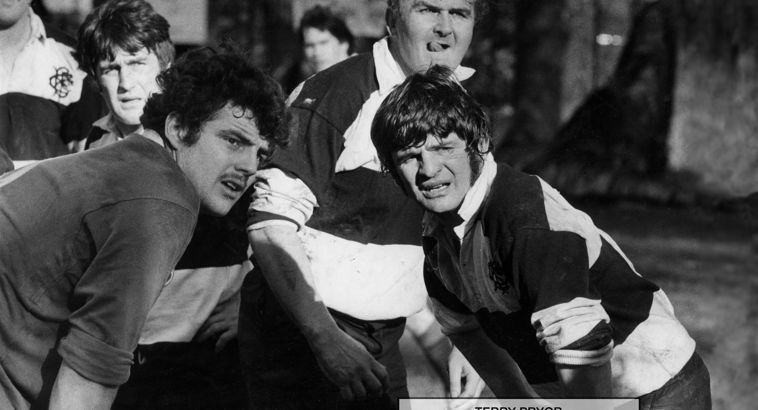

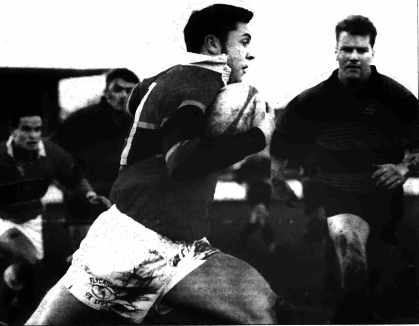

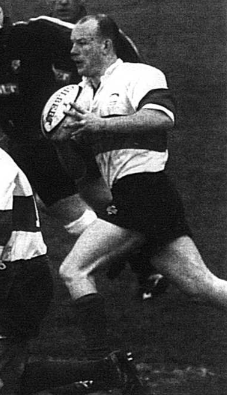

It is John Jackett’s exploits on the rugby field for which he is primarily remembered, and these are of formidable historic import. But the man had talent to burn and the physique to match, and was a ‘crack’, as the Edwardians used to say, at any game he had a mind to try, be it bicycling or billiards.

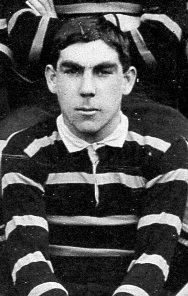

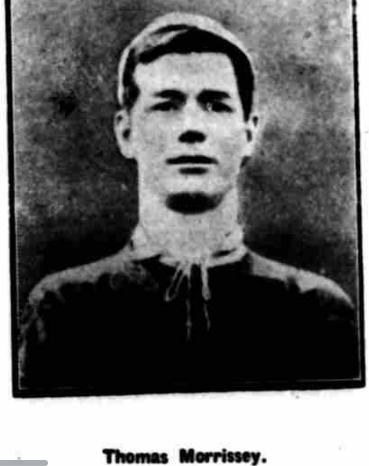

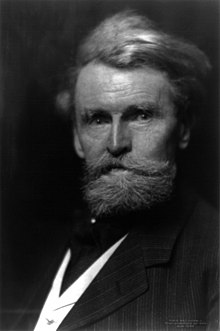

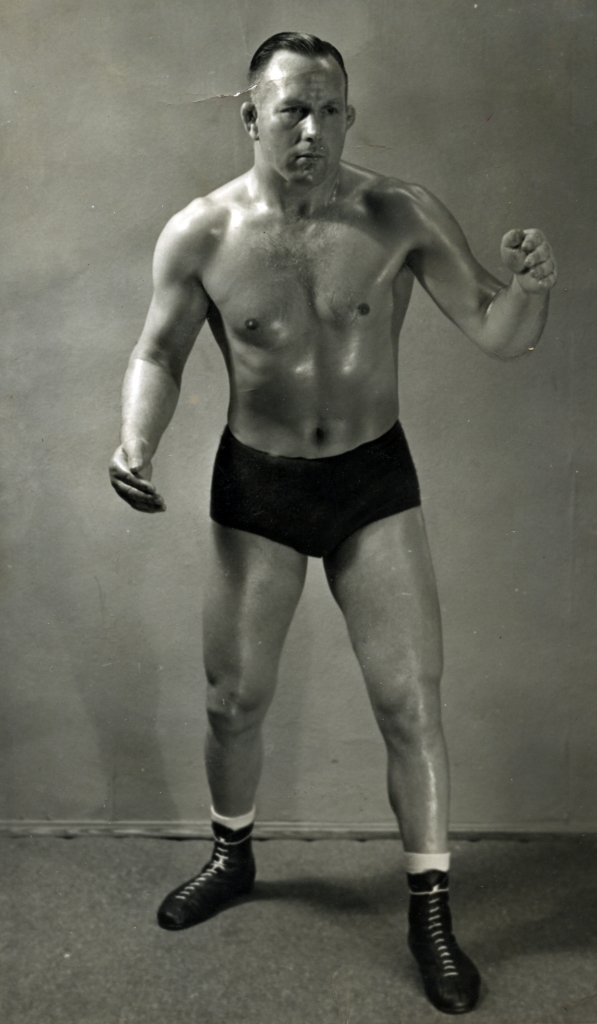

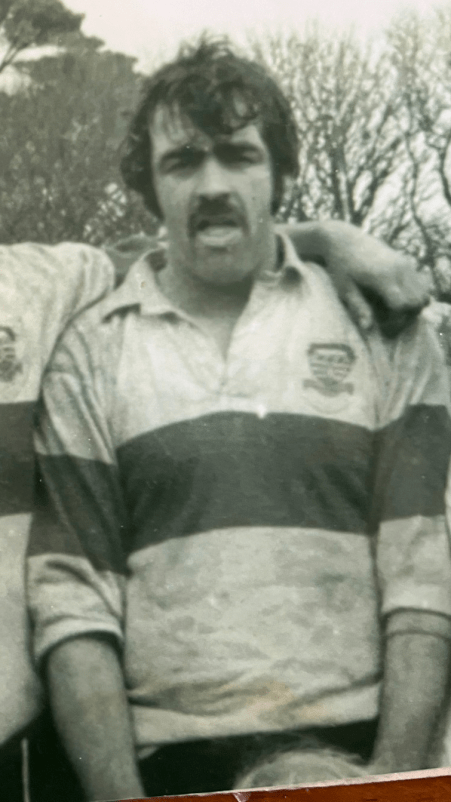

But that wasn’t all. It must be stated that John Jackett also happened to be one handsome devil:

He posed as a model in some of Victorian Cornwall’s most loved paintings, whose artist, Henry Scott Tuke (1858-1929) gained a lasting reputation as having done so much to

…popularize Cornwall as a land of sunshine and health.

Cornish Echo, April 16 1909, p5

Youngsters were in awe of him. His peers admired him. His elders respected him. Women swooned – and so did a few men. You might say he was idolised, and he certainly was4.

But idols can be false, and Jackett was not above spinning the odd yarn to present himself in a more acceptable light – and he had reason to.

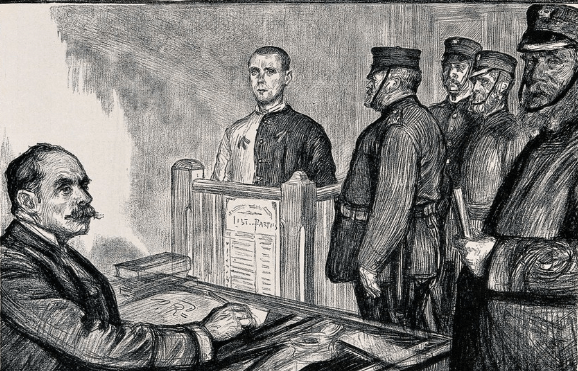

Plus there was one aspect of his character that Jackett, certainly during his years as a Rugby Union player (from the late 1890s to 1911), preferred not to have brought up.

Quite simply, he often played rugby for money. If caught, under the RFU’s amateur codes of the time, he would face suspension and, as a high-profile star, scandal. I’m not referring here to just the well-known RFU investigation of his signing for Leicester. From Jackett’s earliest seasons, a question mark as to his amateur bona fides regularly hovered nearby.

Of course, there’s no concrete proof, no smoking gun. Rugby Union clubs of the early 1900s could probably show today’s sharpest Wall Street sharks a thing or two about cooking the books. But every now and then, you come across a recalled conversation, an insinuation or a rumour that all was not as it seemed.

His signing with the professional Northern Union club Dewsbury in late 1911 was seen cynically by some as his attempt to cash in on his reputation whilst he still had some gas in the tank5. In truth, Jackett had always gone where the money was.

Jackett’s era was also the era of the great middle-class amateur sportsman, where victory on the playing field, if it came at all, had to be carried off with a certain elan:

To achieve success with the appearance of minimal effort was as important to the century-maker at Lord’s as it was to the student with a first from Balliol.

Tony Collins, A Social History of English Rugby Union, Routledge, 2009, p31

Jackett’s apparently effortless dominance of the games he played hides the hours, days, weeks of dedication and graft he devoted to honing his many crafts.

How did he find time to do it? What drove him on? What was he trying to prove, and to whom? This four-part series of posts seeks to provide some answers to these questions.

Jackett’s Steps

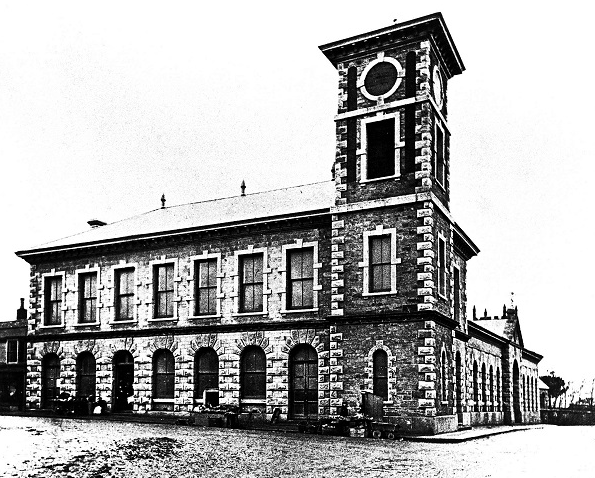

Thomas Jackett epitomised the outdoor, maritime life. A shipwright since his teenage years, he later struck out on his own, manufacturing vessels out of the Victoria Boatyard until the 1930s. The steps I mentioned earlier – Jackett’s Steps – descended from Falmouth’s High Street, past Jackett’s yard and on to the beach. Quiet nowadays, like many of Cornwall’s industrial relics the steps leave little suggestion of what a noisy, busy and commercial place this must have been6.

With Jackett Senior at the helm, the Victoria Boatyard thrived. In 1896 he signed a contract to manufacture a craft for £230 – that’s £25K today8. So knowledgeable of his trade, and so seaworthy were his vessels, that some are still around:

Life must have been comfortable enough for Thomas to indulge his passion: sailing. A member of Falmouth Sailing Club, in 1900 he built Marion, an 18-foot class yacht, for the main purpose of racing her10.

And he was successful. In 1902, for example, Marion won her class in the St Mawes Regatta, Thomas lifting a trophy worth £5, or £500 now11. The Marion was feared for her speed, and was described as

…the fastest boat in her class for many years.

Thomas Jackett’s obituary in the Cornishman, July 7 1938, p2

Such was Jackett’s reputation that in 1911 he accepted a best-of-three-race challenge from a Southampton man who fancied his 18-footer Flatfish to be the fastest on the South Coast.

The two men competed for bragging rights, prestige…and money. Both gentleman-sportsmen chipped in £10 for a £20 prize, or £2K in 2023. One can only speculate as to what was laid down in bets. The Flatfish and her owner arrived in Cornwall by train, and great was the hubbub that ensued.

Billed as ‘The Championship of the South Coast’, it raced out of Falmouth Harbour and over to Pendennis. Jackett was an easy victor, his lasting reputation as a sailor secure. It must have been a long trip back to Southampton13.

Jackett was something of a local hero too; over the course of his life he was known to have saved five people from drowning. On one of these occasions, his son was called on to assist, and as no name was given, it’s impossible to know which of Thomas’s offspring was given such hands-on tutelage in saving lives at sea14.

For Thomas and his wife Emmeline had five male children: William, John, Dick, Fred and Frank. All were more than proficient sailors and rowers, and as their father obviously wasn’t the kind of grizzled old salt who scorned the activities of effete landlubbers, all five took to rugby football with a will15.

Three sons – William, Dick and Fred – followed Thomas into the boatbuilding trade, with Dick taking over the business in the 1930s. Frank found a career from a young age as a public health inspector, and stuck with it16.

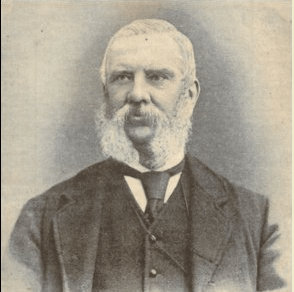

The odd man out in this respect was John Jackett. As Thomas remarked, in a courtroom and under oath, John

…did not work for him…he might come in the shop…but he did not work there…John never took to it…

Cornish Echo, March 8 1901, p4

Was John a disappointment to his father in this regard? If he’d been the only son, perhaps so. Leaving speculation aside, John’s lack of aptitude for the life of a shipwright must have been evident from an early age. The 1891 census tells us that, at the age of 12, he was working as a butcher, and this can’t have lasted long.

Fortunately for the young John Jackett, he had several things in his favour: an amazing sporting ability, a propensity to work hard at things he enjoyed, a keen eye for a financial opportunity (surely a gift bestowed on him by his father), and matinee-idol looks.

Looks first, as it’s these that gave him his start in life.

‘Tuko’

Youth standing sweet, triumphant by the sea,

All freshness of the day

And all the light

Of morn of thy white limbs, firm, bared and bright.From Tuke’s Sonnet to the Sea, published anonymously in The Artist and Journal of Home Culture18

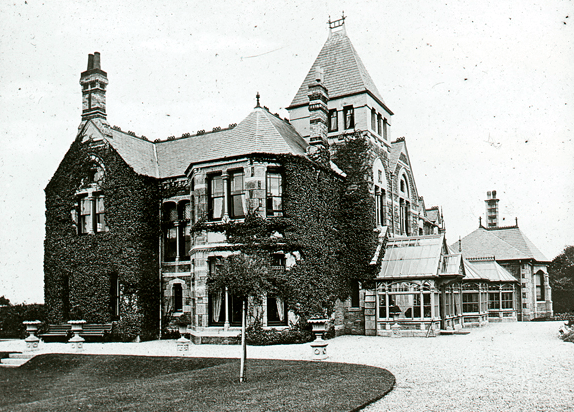

Thomas Jackett was possibly pondering the future of his second son when opportunity came knocking in the early 1890s.

The Impressionist painter Henry Scott Tuke had recently moved to Swanpool from Newlyn. Being as mad-keen a sailor as Jackett himself (Tuke later became Commodore of Falmouth Yacht Club; the two men would also compete together in regattas19), Tuke needed some repairs carried out to his yacht, which is why he visited Jackett’s boatyard. He was also on the lookout for a servant who knew something about sailing, with bed and board thrown in20. Thomas’s ears pricked up. As he was later to state,

…he put him [John] with Mr Tuke.

Cornish Echo, March 8 1901, p4

It was the beginning of a lasting friendship.

While Tuke’s sexuality was probably an open secret, there was never any suggestion of impropriety, with Jackett or any other local lad who posed for his paintings. Tuke was always careful to seek permission from a potential model’s parents before proceeding to employ them21. In many ways, working as a model for Tuke was the ideal ‘seasonal’ job for a teenage boy: you got to row boats, play cricket, swim in the sea, and occasionally pose for a painting. Easy money. As one of Tuke’s models, Tom White, remarked.

I earned altogether about £80 [£3,400] which I used for buying furniture when I got married later in London…he was a great guy!22

Tuke and Jackett’s relationship ran deeper than this. Jackett himself remarked that

Mr Tuke was everything that was wonderful…

Qtd in Henry Scott Tuke 1858-1929: Under Canvas, by David Wainwright and Catherine Dinn, Sarema Press, 1989, p60

How could he say otherwise, when Tuke himself had once saved Jackett from drowning? John was sailing with another man when the boat capsized; his companion, a non-swimmer, held fast to the upturned vessel whilst Jackett calmly treaded water. Tuke swam out and hauled Jackett’s companion to land, assuming John would make it to shore under his own steam. However a tethered fish hook had pierced Jackett’s bare foot when the boat went over – he was trapped. Tuke swam out again, and somehow got both man and boat back to the beach, where the hook was (painfully) extracted23.

(Of course, Tuke had already stepped in to extricate his wayward model from a tight situation several years before this event – but more on that later.)

Tuke for his part seems to have relied on Jackett’s calm, reliable demeanour, his ingrained knowledge of sailing, and the fact that some of his best work featured his servant and friend. Tuke’s art was exhibited in Falmouth as recently as 202125.

The Swimmers’ Pool (1895), one of Tuke’s first paintings where Jackett appears, originally sold for £600 – that’s a whopping £65K today26.

August Blue (1893-4), with Jackett’s modesty covered by means of a towel, is Tuke’s most famous piece. On his death in 1929 it was reproduced in Cornish newspapers27.

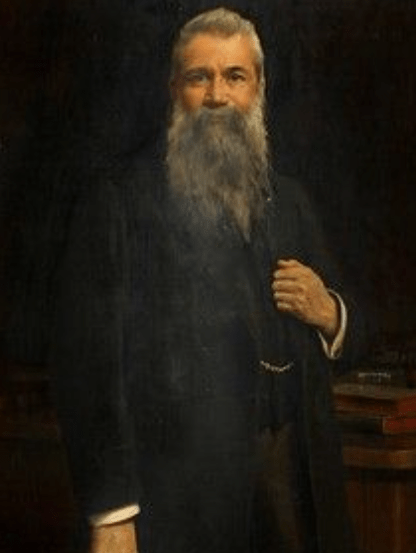

Tuke appreciated Jackett’s looks (and physique) so much as to paint his portrait:

Whether Tuke’s work with Cornish, amateur male models reflects his class-consciousness and social commentary, or if it highlights his desire

…to reintroduce the lost [Greek] tradition of the homoerotic adoration of youths into the fabric of working-class reality…

Jeremy Kim Jongwoo, “Naturalism, Labour and Homoerotic Desire: Henry Scott Tuke”, in British Queer History: New Approaches and Perspectives, ed. B. Lewis, Manchester University Press, 2013, p40

…is a question I shall leave to art historians and queer theorists. That said, 1890s intellectual culture was permeated by a (of necessity) clandestine homosexual movement centred around Oscar Wilde and known as The Uranians30.

Tuke’s association with these somewhat louche figures is well-known. The eminent historian and Uranian Horatio Brown (1854-1926) had his portrait painted by Tuke in 1899, and he evidently found the appearance of the artist’s assistant worth commemorating in verse31:

Hie! Johnnie Jackett!

Ho! Johnnie Jackett!

Young Johnnie Jackett,

Come and live wi’ me;

For life may be a folly,

But we two will make it jolly,

If we sail and swim together, and can live like you and me.

Horatio Brown, “Johnnie Jackett”, from Drift, 1900. With thanks to Donna Westlake, Falmouth Art Gallery

Jackett’s beauty was also versified in John Gambril Nicholson’s (1866-1931) very privately published volume A Garland of Ladslove in 191132.

What Jackett, or indeed Tuke made of all this is unknown. Although Jackett was subject to unwanted advances from at least one (that we know of) Falmouth man, his relationship with his employer and friend remained just that33.

In any case, Tuke and Jackett had something much more in common: sport. The emergence of ‘modern’ sports in the 1850s which supplanted more traditional, plebeian forms of recreation (cudgelling, hurling, bareknuckle boxing etc) has been seen as the need for

…an institution of social fatherhood to provide training in manly pursuits – war, commerce, government…The popularity of sport expressed this shift from belief…to the man-made, knowable and material world of human endeavour and the body…

Varda Burstyn, The Rites of Men: Manhood, Politics, and the Culture of Sport, University of Toronto Press, 1999, p45, 76

Moreover, in Britain the rise of physical culture was in part a reaction to a realisation in the 1890s that the sun might finally be beginning to set on the Empire. It was time to harden yourself against decadent temptation (as exemplified in the Uranian movement), and prepare for imminent conflict35.

Recreation can take many forms. Not only a keen sailor, Tuke had one of his studios converted to a billiards room36, and doubtless taught Jackett how to play the game. Jackett, naturally, proved more than handy with cue in hand37.

The model Tom White also recalled that Tuke had a practice area for cricket set up behind another one of his studios. Tuke had learnt the game in Middlesex, and was acquainted with such Victorian giants of whites and willow as C. B. Fry, Prince Ranji and W. G. Grace. He even had his own banal cricketing nickname: ‘Tuko’38.

Jackett was playing in matches as early as 1896. Throughout the 1900s, he and ‘Tuko’ played for Falmouth Church Institute CC, with Jackett heading the batting averages for the 1907 season40.

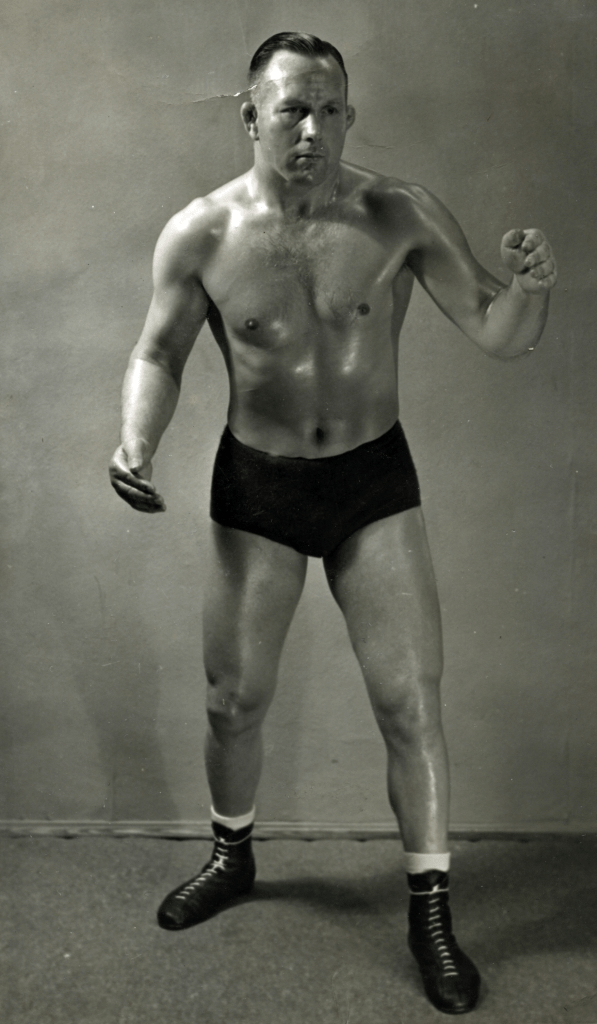

As to the more manly pursuits, Jackett was to state in an interview that he was a “clever” boxer41, and he may well have been. However, I can find no report of him ever having fought an organised bout. That’s ‘organised’. When he squared up on the streets of Falmouth to a burly prizefighter from Plymouth whose dog had been worrying his, Jackett came away minus a tooth, and a jaw one good clout away from being broken42.

As his features earned him money, Jackett may have concluded that having them rearranged by someone’s knuckles was financially ill-advised, and equally painful43.

Although they cycled together, and Tuke tried to watch every rugby match he played, Jackett’s job with Tuke was genuinely seasonal44. As he was to state,

I am only with Mr Tuke seven months in the year. He is five months in London, and the rest of the time I live on my father…

Cornish Echo, February 8 1901, p5

(We will be examining the truthfulness of how much Jackett ‘lived on his father’ in due course.)

When he was in Tuke’s company, though, the young Jackett must have learned a valuable lesson: that of the sheer single-minded devotion one must have to excel in your chosen field. When an interviewer remarked on the seemingly easy rapidity with which Tuke produced his wonderful pictures, the artist replied,

Only after long practice in the open, on top of six or seven years’ grinding at the Slade and in Paris.

Black and White, August 12 1905, p12

In the lengthy hours Jackett must have posed for Tuke, conversed with him, or merely just watched the man at work, the lesson must surely have been absorbed. If you want to be the best, you have to put in the graft.

As Jackett himself would later write whilst in New Zealand with the British Lions,

…nothing tends to promote combination and judgment more than constant practice…

Evening Star, January 13 1908, p8

Even by 1899, the Vice President of Falmouth RFC stated that John Jackett was an example to all players,

…being always in strict training…

Lake’s Falmouth Packet, November 18 1899, p5. Emphasis mine

Realising that what you do off the pitch is as important as what happens on it, Jackett took care of his health too. When interviewed in 1902, he stated that his powers of recovery were due to

…the fact that he is a teetotaller.

Lake’s Falmouth Packet, June 14 1902, p5. With thanks to Victoria Sutcliffe and Danny Trick of Falmouth RFC for showing me this.

Building boats wasn’t for him. His brothers held good jobs. For practically half the year, he had no income, excepting his father’s good grace. Necessity was about to collide with willpower.

John Jackett picked something he was good at, and tried to make a living from it.

That thing was a sport. It was fast, exciting, risky, and brought its champions fame and ready money.

Track cycling.

Palmares

Bicycle racing is

…an excellent example of a new mass-spectator sport in the mid-19th century, during which there was an urge to both market and consume a novel spectacle.

Andrew Ritchie, “The Origins of Bicycle Racing in England: Technology, Entertainment, Sponsorship and Advertising in the Early History of the Sport”, Journal of Sport History, Vol. 26.3 (1999): p489-520

The advances made in mass-manufacturing methods made development and production of machines easier; entrepreneurs saw a new money-spinner; riders naturally wanted to pit their wits against each other, and people with expendable income and leisure time felt moved to witness the thrills and spills.

Without the Industrial Revolution, recreational cycling and/or bike racing would not have become the phenomenon it was. The invention in the 1880s of the safety bicycle and the pneumatic tyre made cycling a more practical and comfortable prospect. Although in the 1890s a high-end machine could set you back £30 (£3,200 today), factory-line production made bikes affordable for members of the upper working-class. Mirroring the rise of modern football (Association, Union and Northern), cycling clubs appeared all over the country and, sure enough, competitions were held47.

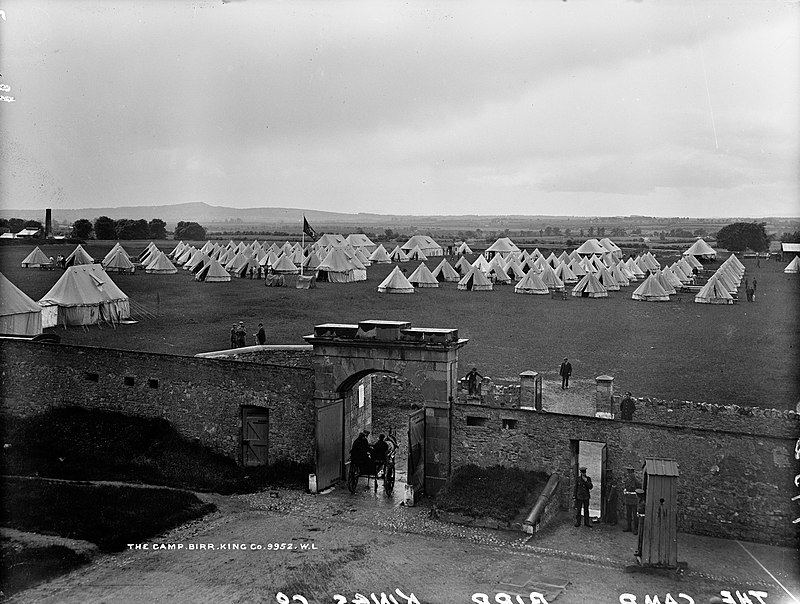

The development in many towns of multi-purpose sports and recreation grounds meant that, when in 1890 the National Cyclists’ Union banned racing on open roads, an infrastructure existed to accommodate track cycling48.

All this happened in Cornwall too. And John Jackett was one of the first Cornish cycling stars.

In the sport’s earliest years, meets were often an adjunct of a well-established local event. The first report of an organised bike race in Cornwall (that I can find) was held at Falmouth Regatta in August 186950.

In 1871 Penryn Regatta held, with Penny Farthings and narrow thoroughfares, the terrifying spectacle of a mass street race pell-mell around the town. By 1875 the organisers of Zelah Feast had moved with the times, its cycling competition being the “chief attraction” of the festivities51.

It rapidly became apparent that race meets were an event in themselves. 3,000 watched the day’s thrills and spills at Plymouth in 1878, which featured riders from Cornwall53. Newspapers increased their coverage, which of course fed the publicity mill. In the 1890s, the Cornishman‘s dedicated cycling columnist rejoiced in the pseudonym ‘Inflatable’, while Lake’s Falmouth Packet‘s man contributed under the guise of ‘Pneumatic’54.

Clubs formed to accommodate and regulate the new craze. Launceston could boast one as early as 1878; hot on its heels (or wheels) was the Penzance ‘First and Last’ Club, certainly in existence by 187955.

The mining district’s ‘One and All’ club was at first inaugurated in 1881 for riders of both Camborne and Redruth. Perhaps predictably, the unity was short-lived, and by 1883, with no sense of irony, Redruth had its own One and All Club…as did Camborne56.

Open-air velodromes began to appear in the 1880s. New recreation grounds and sports fields provided ideal locations, plus the owners could demand an entry fee – you couldn’t very well charge people admission when they’re stood on a pavement hollering at a road-race. Penzance had a (much criticised) grass track circling its cricket pitch from 188658. Falmouth’s Recreation Ground on Dracaena Avenue opened in 1889 with a state-of-the-art cinder track, unashamedly described in a local ‘paper as

…the best cinder track in the South of England…

Lake’s Falmouth Packet, August 1 1891, p559

The Redruth One and All track, by contrast, was lambasted for being

…a rough and hilly field…

Cycling, January 16 1892, p443

To be sure, there were no regulations or stipulations for velodromes at this time; Bodmin’s track was grass too60.

All this goes to show that, by the time John Jackett began to make his mark in the sport, Cornish track racing was an established and popular element of the sporting year. It had its own calendar of events, its own venues, its own following and a multitude of riders.

Jackett was the pick of the bunch.

He was still a teenager when he began to make a name for himself in local meets, and barely eighteen when he travelled to North Cornwall for the “auspicious” annual athletics meet of Launceston Harriers61.

In between events, the 1,500-strong crowd (most of whom patronised a purpose-built grandstand) were entertained by Launceston Volunteer Band. Prizes totalled over 30 guineas, or north of £3K now.

Like practically all the meets Jackett appeared in, this one recognised the Amateur Athletics Association and National Cyclists’ Union, thus

…totally barring the professional element.

Cornish and Devon Post, June 27 1896, p8

This was a competition for the gentleman-amateur, who wouldn’t tolerate any shortcomings on the track being laid bare by a socially inferior being. Losing to a Bank Manager or a lawyer, say, would have been acceptable, but having to cough on the dust of a former miner-turned-pro? The indignity…62

Jackett won the mile race by a yard, but crashed in the three-miler.

When he starred in the August Bank Holiday meet on his home turf, the cycling pundit ‘Pneumatic’ observed that

…he was in fine form, and was responsible for much high pressure…all his wins were popular…

Lake’s Falmouth Packet, August 8 1896, p8

He took the mile prize, the club two-mile contest, and came second in the half-mile championship of all Devon and Cornwall. Falmouth’s Mayor singled out his “plucky riding”63.

Jackett took the three-mile prize at a meet of the Truro Church Insititute, with the trophy being presented to him by Truro’s MP, Edwin Lawrence.

Though Jackett was keen to stress his amateur status, in 1901 he himself estimated that he had won over £150 in prizes, or £15K today65.

Considering he had only been racing competitively since 1896 (and his peak years can be judged to be from 1897-99, before his rugby career genuinely took off), this is impressive. For example, his earnings from a single day’s racing at St Austell in 1898 were £5 5s, or over £540 nowadays66. At Sidmouth in 1897 he was presented with a set of gold studs for winning the mile handicap which, to modern eyes, was the most edifying award on offer: other victors could hold aloft a cigarette case, or a box of fine cigars67.

If not a professional cyclist, Jackett certainly took a professional attitude. We have already noted his diligence in honing his rugby skills, and he was similarly dedicated to his bike. In 1896 he and another rider spent

Every night for the week…practising hard on the Recreation Ground track, and with excellent results…

Lakes Falmouth Packet, August 1 1896, p5. With thanks to Victoria Sutcliffe and Danny Trick of Falmouth RFC for showing me this.

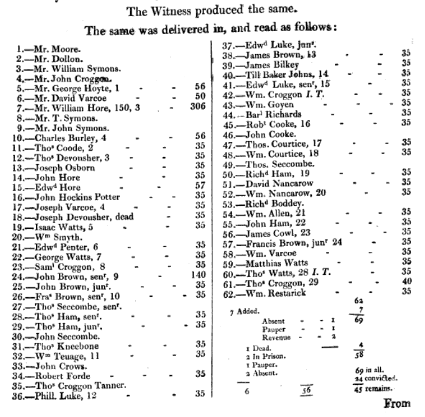

He raced as frequently as he trained, and in 1897 had a full programme68:

| Date | Location | No. of races | Wins |

| April 18 | Falmouth | 2 | 0 |

| May 28 | Bodmin | 1 | 0 |

| June 7 | Plymouth | 2 | 0 |

| June 16 | St Austell | 2 | 0 |

| June 20 | Falmouth | 3 | 1 |

| July 9 | Falmouth | 4 | 2 |

| July 15 | Camborne | 2 | 1 |

| August 2 | Falmouth | 3 | 2 |

| September 4 | Exeter | 1 | 0 |

| September 7 | Sidmouth | 1 | 0 |

At Falmouth on July 9th, he took the One Mile County Championship, being “a popular winner by a few feet” in a two-horse race for the finish69.

At Camborne, in front of a “commodious” grandstand containing the well-to-do, his cycling was a “revelation”. He was also (erroneously) noted as being the Cornish three-mile champion70, and further stoked his own myth by casually remarking to a reporter that he intended to break the Camborne to Penzance record71.

His local ‘paper was sure to list his palmares, or achievements over the 1897 season: 8 firsts (I can only find 6), 5 seconds, and 7 thirds – plus the One Mile Championship72.

What we are not told is how Jackett found the time, and the funds, for all his training, travelling (on a train, with a bike) and racing. Would a gentleman-amateur be present at most, if not every, major cycling meet in Cornwall and South Devon over the course of a season? Was Jackett not in the employ of Mr Tuke? (Tuke, it seems, kept his servant on a pretty loose rein73.) Surely the Devon meets would have involved overnight stays?

We do know something of his racing style, however. In May 1898, at Home Park, Plymouth, he came third in a one-mile race, the victim of his own impetuosity. The riders began so slowly as to be booed and catcalled by spectators thirsty for action, and Jackett reacted, kicking on to attempt to win in a blaze of glory, but ultimately blowing himself out74.

He had guts too, and was prepared to mix it in a tight finish. At the opening of Camborne Recreation Ground in June 1898, the five-mile race boiled down to a thrilling sprint finale between the front three riders – none of whom made it past the line. Jackett was one of the three, flung all over the track in a nasty pile-up76.

The new cinder track at Camborne was criticised for its shallow banking, it being observed that this hindered Jackett’s tactics77. In other words, he preferred to use the high banking on a track (which Falmouth’s possessed), and swoop down unawares on his opponents from behind, hoping to catch them off-guard.

John Jackett must have been box-office.

How good a racer was he? Is it possible to measure Jackett’s track prowess and ability over a hundred and twenty years after he rode? In a way, we can.

In June 1898 at Falmouth, he won a gold cup worth £4 (£430 today) for taking first in the 25-mile race. He was timed at 70 minutes 45 seconds78. This gives us an average speed of 21.2mph.

21.2mph, for 70 minutes, on a rather cumbersome steel-framed machine with no gears. Falmouth’s cinder track would have been heavy going too, and Jackett would have worn (at best) cotton breeches and a cotton jersey. I put the question to Richard Pascoe, ex-professional cyclist and now Team Principal of Saint Piran Pro Cycling:

Judging by the size of his chest and the strength of his limbs as illustrated in Tuke’s paintings, it’s plain to see the man had an ‘engine’, as we call it, and would have been successful in any sport. I’d say Jackett was a very fine athlete, and certainly possessed the minerals required to be the best. Falmouth’s cinder track was not a fast one, and that speed under those conditions is very impressive. Had there been a Saint Piran’s pro cycling team in that era, he would have certainly been on my books!

Given a modern machine, track conditions, training and clothing, Jackett had the physiognomy to match today’s pros. But then, all the Jackett boys had decent engines. John often rowed competitively with his brother Dick, who was a five-time Cornish champion79. However, in the Jackett household, John was the sole cyclist.

Although he continued to race sporadically into the 1900s, and even guested (doubtless for a small consideration) at a meet in Leicester80, Jackett’s glory years as a cyclist were relatively short-lived.

Maybe he concluded the risks outweighed the rewards. He crashed, punctured or simply ran out of steam easily as often as he won or placed, yet his reputation as a champion with amazing powers of stamina endured. At Camborne in 1900 he was the rider selected to demonstrate to the crowds an exhibition of being paced behind a motorbike81.

Cycling had brought John Jackett recognition, prestige and an (irregular) income. It also brought him something else: a fanbase.

Local girls would visit his father’s house, ostensibly to admire Jackett’s trophies, but probably to grab a glimpse of the handsome young buck too82.

Very possibly, one of these young ladies who came calling was a Miss Caroline Over.

She and John Jackett became friendly. Very friendly.

The serious consequences of their relationship will be revealed in In Search of John Jackett, Part Two, which you can read by clicking HERE.

Many thanks for reading; follow this link for more top blogs on all things Cornwall: https://blog.feedspot.com/cornwall_blogs/

Do you enjoy my work?

All content on my website is absolutely FREE. However managing and researching my blog is costly! Please donate a small sum to help me produce more fascinating tales from Cornwall’s past!

Your contribution is greatly appreciated.

DonateReferences

- Jackett wrote an article on fullback play for Fry’s Magazine of Sport, Travel and Outdoor Life, Vol 11.7, 1911, p45-8. Judge Granger’s remarks are recorded in the Cornish Echo, February 8 1901, p5. Sallie Jackett is quoted in Henry Scott Tuke 1858-1929: Under Canvas, by David Wainwright and Catherine Dinn, Sarema Press, 1989, p60. The journalist’s observation about Jackett is from the Evening Mail, December 1 1905, p6.

- Read about Holloway’s career here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2022/09/06/murder-debt-riot-richard-holloway-redruth-solicitor/; Small’s exploits here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2021/12/20/the-notorious-beatrice-small-fortune-teller/; Burnett’s murder here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2024/03/23/gallows-bell-the-murder-of-joseph-burnett/; and Rabey’s complex scams here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2022/03/20/they-died-with-their-shoes-on-the-career-of-paul-rabey-the-younger-part-one/

- Image from: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-9019-1-4-4-7/e-a-osborne-postcard-photograph-of-johnny-jackett#0

- An interview with Jackett in the Dewsbury Reporter of March 10, 1928 alludes to this.

- Certainly that is the view of the Royal Cornwall Gazette, January 4 1912, p3.

- Information from the 1871 census, and the following piece on Jackett’s yard: https://falmouthhistory.wordpress.com/victoria-boat-yard-burts-yard/

- Image from: https://falmouthhistory.wordpress.com/victoria-boat-yard-burts-yard/

- Cornish Echo, March 21 1896, p5.

- Image from: https://www.falmouthclassics.org.uk/participating-boats-2024/curlew/

- Information from: https://www.stmawessailing.co.uk/fleets/18-foot-restricted/

- Royal Cornwall Gazette, September 11 1902, p2. Cornish newspapers of the early 1900s are littered with examples of Jackett’s sailing prowess.

- Image from: https://www.falmouthharbour.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/FH_Then-Now.pdf

- Cornish Echo, May 26 1911, p7, and August 4, p5.

- Cornish Echo, May 12 1905, p5.

- Emmeline Medlin was born c1859, she and Thomas Jackett married in 1874. Information from Ancestry. That all five brothers played rugby is stated in Dick Jackett’s obituary, West Briton, July 28 1960, p14. Thomas Jackett’s obituary in the Cornishman (July 7 1938, p2), notes he was a life-member of Falmouth RFC. The Cornish Echo (August 15 1902, p5), states he was also a Vice President of the junior Falmouth One and All RFC, along with Henry Scott Tuke.

- Information from 1901 and 1911 census, and Dick Jackett’s obituary in the West Briton, July 28 1960, p14.

- Image from: https://www.pinterest.co.uk/pin/tuke-henry-scott-head-of-johnny-jackett–741897738608095578/

- Quote from: https://fortyfoot.livejournal.com/34942.html. For more on The Artist and Journal of Home Culture, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Artist_and_Journal_of_Home_Culture

- Tuke’s election as Commodore is reported in the West Briton, September 14 1911, p4. For example, Thomas Jackett and Tuke both raced in the Portscatho Regatta (West Briton, August 18 1904, p2), and the Mylor Regatta (Commercial, Shipping and General Advertiser, August 26 1899, p3).

- Henry Scott Tuke 1858-1929: Under Canvas, by David Wainwright and Catherine Dinn, Sarema Press, 1989, p56-60.

- Wainwright and Dinn, Under Canvas, p56.

- Tom White’s recollections of his summers with Tuke are available here: http://www.artcornwall.org/features/Tuke/Henry_Scott_Tuke_Tom_White.htm

- Cornish Echo, July 20 1906, p5.

- Image from: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-9019-1-4-6-5/photographer-unknown-photograph-showing-henry-scott-tuke-and-johnny-jackett-on-tukes-yacht

- Wainwright and Dinn, Under Canvas, p56-60. For more information on the 2021 Tuke Exhibition, see: https://www.falmouthartgallery.com/Exhibitions/2021/1738~Henry_Scott_Tuke. I am grateful to Donna Westlake of Falmouth Art Gallery for her assistance.

- From Henry Scott Tuke: A Memoir, by Maria Tuke Sainsbury, Martin Secker, 1933, p114.

- The painting was described as such in Tuke’s obituary, Cornishman, March 14 1929, p7. August Blue was reproduced in the West Briton, March 21 1929, p10. The Daily Mirror of May 8 1914 (p16) shows a photograph of Tuke painting a naked Jackett on the beach.

- Image from: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/tuke-august-blue-n01613

- Image from: https://www.paintingmania.com/johnny-jackett-269_54834.html

- For more on The Uranians, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uranians, and “The Cult of Homosexuality in England 1850-1950” by Noel Annan, Biography, Vol 13.3, 1990, p189-202.

- For more on Horatio Brown, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horatio_Brown. His portrait can be seen here: https://www.tate-images.com/MB8353-Register-of-paintings-by-Henry-Scott-Tuke-Print-of.html

- Wainwright and Dinn, Under Canvas, p60. For more on Nicholson, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Gambril_Nicholson. Putting it bluntly, nowadays we would describe Nicholson as a paedophile.

- Wainwright and Dinn, Under Canvas, p57.

- Marriage information from Ancestry. Images from: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-9019-1-4-2-24/photographer-unknown-photograph-of-henry-scott-tuke-standing-with-johnny-jackett-seated, and https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-9019-1-4-2-10/photographer-unknown-glass-negative-photograph-showing-henry-scott-tuke-and-johnny-jackett. Sallie’s memories of Tuke are mentioned in Wainwright and Dinn, Under Canvas, p57.

- Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire 1875-1914, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987, p302-327.

- Sainsbury, Tuke: A Memoir, p123.

- A concert held for the Falmouth Liberal Club saw Jackett come second in a billiards tournament. Cornish Echo, April 19 1901, p7.

- See Tom White’s memories here: http://www.artcornwall.org/features/Tuke/Henry_Scott_Tuke_Tom_White.htm. Tuke’s love of cricket is recalled in Sainsbury, Tuke: A Memoir, p141-52.

- The image is from Tuke’s diary, which can be viewed here: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/items/tga-9019-1-1-1/diary-of-henry-scott-tuke/3

- Cornish Echo, May 30 1896, p5, and September 20 1907, p8.

- Dewsbury Reporter, March 10, 1928.

- Cornish Echo, July 25 1896, p4.

- Wrestling didn’t suit Jackett much either. Another youth dislocated his shoulder when he was ten. Lake’s Falmouth Packet, September 22 1888, p5.

- Wainwright and Dinn, Under Canvas, p60. An avid rugby fan, Tuke was Vice President of Falmouth One and All RFC. Cornish Echo, August 15 1902, p5.

- Images from: https://www.tate-images.com/preview.asp?item=MB8827&itemw=4&itemf=0001&itemstep=1&itemx=44, and https://www.falmouthartgallery.com/Collection/2015.8.111

- Image from: https://saintpiranprocycling.com/news-stories/2020/3/9/saint-piran-2020-team-launch

- Summarised from: Andrew Ritchie, “The Origins of Bicycle Racing in England: Technology, Entertainment, Sponsorship and Advertising in the Early History of the Sport”, Journal of Sport History, Vol. 26.3 (1999): p489-520, and David Rubinstein, “Cycling in the 1890s”, Victorian Studies, Vol. 21.1 (1977), p47-71.

- See: https://www.britishcycling.org.uk/search/article/bc-50th-The-Story-behind-British-Cyclings-formation

- For more on the birth of Camborne Rugby Club, see: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/08/26/cambornes-feast-day-rugby/

- Cornish Echo, August 21 1869, p1.

- Commercial, Shipping and General Advertiser, August 19 1871, p4; Royal Cornwall Gazette, May 8 1875, p5.

- Image from: https://cornishnationalmusicarchive.co.uk/content/cornish-tea-treats-across-the-patch-t-z/

- Cornish and Devon Post, June 15 1878, p5.

- For example, Cornishman, December 19 1895, p7; and Lake’s Falmouth Packet, August 8 1896, p8.

- Cornish and Devon Post, June 15 1878, p5; Cornubian and Redruth Times, October 29 1886, p7.

- Cornish Telegraph, March 17 1881, p5, and June 2 1883, p7. For more on the Camborne-Redruth rivalry, see my post here: https://the-cornish-historian.com/2023/09/02/camborneredruth-the-oldest-continual-rugby-fixture-in-the-world-part-one/

- Image from: https://www.oldvelodromes.co.uk/HTML%20tracks/625.html

- Information from: https://www.oldvelodromes.co.uk/BookSmall.html. The Cornish Telegraph took issue with Penzance’s track on August 1 1889, p5.

- Cornish Telegraph, August 1 1889, p5.

- As noted in the Western Morning News, April 7 1896, p5.

- The report of this meet is in the Cornish and Devon Post, June 27 1896, p8. Jackett’s name starts to appear in reports of cycle races from 1894: Cornish Echo, May 18 1894, p7.

- To be sure, amateurs would not have raced with professionals – the gulf in quality would have probably been embarrassing. For more on the Victorian caste (or class) system of amateur and professional sportsmen, see: Andrew Ritchie, “The Origins of Bicycle Racing in England: Technology, Entertainment, Sponsorship and Advertising in the Early History of the Sport”, Journal of Sport History, Vol. 26.3 (1999): p489-520.

- Lake’s Falmouth Packet, August 8 1896, p8.

- Image and information from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edwin_Durning-Lawrence

- Cornish Echo, February 8 1901, p5.

- Western Morning News, June 9 1898, p7.

- Devon and Exeter Gazette, September 8 1897, p5.

- Information from: Cornish Echo, April 23, p5; West Briton, May 6, p6, July 15, p10, July 22, p3, August 5, p7; Western Morning News, June 8, p6, June 17, p6, June 23, p7; Exeter Flying Post, September 4, p8; Sidmouth Observer, September 8, p5.

- West Briton, July 15 1897, p6.

- Cornishman, July 22 1897, p3.

- Cornishman, September 9 1897, p3.

- Cornish Echo, February 8 1901, p5.

- Lake’s Falmouth Packet, October 2 1897, p4.

- Western Evening Herald, May 3 1898, p4.

- Image from: https://www.greensonscreen.co.uk/argylehistory.asp?era=1902-1903_1

- Cornish Post and Mining News, June 30 1898, p7.

- Cornish Post and Mining News, July 7 1898, p7.

- Cornish Echo, June 17 1898, p5.

- See Dick Jackett’s obituary, West Briton, July 28 1960, p14. The brothers competed in the Portscatho Regatta: West Briton, August 18 1904, p2.

- Leicester Daily Press, May 28 1906, p7.

- Cornishman, September 6 1900, p6.

- Lake’s Falmouth Packet, February 3 1900, p8.